Published online Oct 21, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i39.4938

Revised: July 18, 2010

Accepted: July 25, 2010

Published online: October 21, 2010

AIM: To investigate possible associations of anti-nuclear envelope antibody (ANEA) with disease severity and survival in Greek primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) patients.

METHODS: Serum samples were collected at diagnosis from 147 PBC patients (85% female), who were followed-up for a median 89.5 mo (range 1-240). ANEA were detected with indirect immunofluorescence on 1% formaldehyde fixed Hep2 cells, and anti-gp210 antibodies were detected using an enzyme linked immunosorbent assay. Findings were correlated with clinical data, histology, and survival.

RESULTS: ANEA were detected in 69/147 (46.9%) patients and 31/147 (21%) were also anti-gp210 positive. The ANEA positive patients were at a more advanced histological stage (I-II/III-IV 56.5%/43.5% vs 74.4%/25.6%, P = 0.005) compared to the ANEA negative ones. They had a higher antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA) titer (≤ 1:160/> 1:160 50.7%/49.3% vs 71.8%/28.2%, P = 0.001) and a lower survival time (91.7 ± 50.7 mo vs 101.8 ± 55 mo, P = 0.043). Moreover, they had more advanced fibrosis, portal inflammation, interface hepatitis, and proliferation of bile ductules (P = 0.008, P = 0.008, P = 0.019, and P = 0.027, respectively). They also died more frequently of hepatic failure and/or hepatocellular carcinoma (P = 0.016). ANEA positive, anti-gp210 positive patients had a difference in stage (I-II/III-IV 54.8%/45.2% vs 74.4%/25.6%, P = 0.006), AMA titer (≤ 1:160/> 1:160 51.6%/48.4% vs 71.8%/28.2%, P = 0.009), survival (91.1 ± 52.9 mo vs 101.8 ± 55 mo, P = 0.009), and Mayo risk score (5.5 ± 1.9 vs 5.04 ± 1.3, P = 0.04) compared to the ANEA negative patients. ANEA positive, anti-gp210 negative patients had a difference in AMA titer (≤ 1:160/> 1:160 50%/50% vs 71.8%/28.2%, P = 0.002), stage (I-II/III-IV 57.9%/42.1% vs 74.4%/25.6%, P = 0.033), fibrosis (P = 0.009), portal inflammation (P = 0.018), interface hepatitis (P = 0.032), and proliferation of bile ductules (P = 0.031). Anti-gp210 positive patients had a worse Mayo risk score (5.5 ± 1.9 vs 4.9 ± 1.7, P = 0.038) than the anti-gp210 negative ones.

CONCLUSION: The presence of ANEA and anti-gp210 identifies a subgroup of PBC patients with advanced disease severity and poor prognosis.

- Citation: Sfakianaki O, Koulentaki M, Tzardi M, Tsangaridou E, Theodoropoulos PA, Castanas E, Kouroumalis EA. Peri-nuclear antibodies correlate with survival in Greek primary biliary cirrhosis patients. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(39): 4938-4943

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i39/4938.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i39.4938

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a chronic, progressive, cholestatic liver disease of probable autoimmune etiology, characterized by destruction of small intrahepatic bile ducts, portal inflammation, and, eventually, development of liver cirrhosis and hepatic failure. Elevated cholestatic enzymes, compatible liver histology, and detectable antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA), at titers higher than 1:40, are the three diagnostic criteria used for the diagnosis of PBC. Two of the three criteria suffice for making a definite diagnosis of PBC[1].

In fact, AMA are the specific marker of PBC, detected in 90%-95% of patients[2]. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are also present in 30% to 50% of patients[3-6], and are detected by indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) with various patterns. The peri-nuclear pattern is the most common IIF pattern of ANA, which detects nucleoporin 62 (p62)[7,8] and gp210[4] (nuclear pore complexes, NPC), as well as the lamin B receptor and lamin A/C[9,10], all antigens of the nuclear envelope. The multiple nuclear dot IIF pattern of ANA, is due to nuclear antigens such as sp100, SUMO, and PML. Another ANA IIF pattern found in PBC patients is the anti-centromere (ACA) one[11,12].

Although AMA are not associated with disease progression[1], ACA and anti-nuclear envelope antibody (ANEA) (ANA against the nuclear envelope antigens) seem to be associated with disease severity[4,13]. In fact, anti-NPC presence has been associated with more active and severe disease[7,13]; anti-gp210 and ACA positive patients have been reported to be associated with either hepatic failure or portal hypertension respectively[4,13,14]. However a study on Spanish and Greek patients did not confirmed these findings[15].

The purpose of the present study is to examine associations between the presence of serum ANEA and the severity and survival in a homogeneous cohort of Greek patients with AMA positive and negative PBC, in a single referral centre.

From January 1989 to June 2009, 232 PBC patients were diagnosed by standard criteria and followed up at the Department of Gastroenterology of the University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete. Patients that had frozen (-80°C) serum collected at diagnosis, had negative hepatitis viral markers, were regularly followed up and gave their consent, were included in the study. These criteria were fulfilled by 147 patients. They were followed-up for 1-240 mo (mean 96.1 ± 55.8 mo, median 89.5 mo) after the initial diagnosis of PBC. Nineteen (12.9%) patients were AMA negative and 128 (87.1%) were AMA positive, with a titer > 1/40, M2 positive. Twenty-two patients (15%) were males and 125 (85%) were females. The mean age at diagnosis was 59.2 ± 10.9 years (median 60, range 31-80). According to the Ludwig classification, 97 patients (66%) were at an early stage (I-II), 50 (34%) were at a late stage (III-IV), of whom 32/50 were at stage IV. The mean Mayo risk score at the time of diagnosis was 5.1 ± 1.6. All patients were treated with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) at a dose of 13-15 mg/kg, starting after the time of serum collection. Other coexisting autoimmune diseases were: Sjogren syndrome in 12 patients, Raynaud phenomenon in two, psoriasis in one, sarcoidosis in one, discoid lupus erythematosus in one, autoimmune atrophic gastritis in two, and vitiligo in one.

During the follow-up period 14 patients developed variceal bleeding, 15 developed ascites, two developed hepatic encephalopathy, and six developed hepatocellular carcinoma. Four patients underwent orthotopic liver transplantation. Thirty patients died during follow-up (five from liver unrelated causes). The remaining 117 patients are alive and are still being followed up at our Department at the end of the study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital. All patients have given a written, informed consent.

The Autoantibodies studied were correlated with clinical data, histology at diagnosis, the major events occurring during the follow-up period, and survival.

Ninety-eight biopsy specimens with more than three portal tracts were reexamined and graded by a single pathologist. The histological variables analyzed included: fibrosis (1-3) (1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe), interface hepatitis (0-3) (0 = absent, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe), portal inflammation (1-3) (1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe), intralobular inflammation (0-2) (0 = absent, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate), epithelioid granulomas (0-1) (0 = absent, 1 = present), and proliferation of bile ductules (0-1) (0 = absent, 1 = present).

Human Hep2 cells (larynx and cervical carcinoma) were used. The cells were cultured in Minimum Essential Medium supplied with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin and 1% non-essential amino acids. They were maintained in humidified atmosphere at 37°C and 5% CO2. All the culture media were from Gibco (Invitrogen, UK)

An IIF assay of Nova Lite™ (IFA) ANA plus Mouse Kidney & Stomach (Inova Diagnostics, San Diego CA, Inc) was used for screening and semi-quantitative determination of AMA IgG antibodies, according to the manufacture’s instructions.

IIF was performed for detection of ANEA, as previously described[16]. Briefly, Hep2 cells were grown overnight on coverslips and washed with PBS (Gibco, Invitrogen, UK).

The cells were fixed with 1% and 4% formaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) for 10 min. The cells were washed with PBS. To quench auto-fluorescence and enhance antigenicity, the fixed cells were incubated with 20 mmol/L glycine (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) in PBS for 5 min. After blocking with PBS containing 0.2% TritonX-100, 2 mmol/L MgCl2, and 1% gelatin from cold water fish skin (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) for 10 min, cells were incubated with serum (dilution 1:80) in blocking buffer for 45 min. Subsequently, the coverslips were washed with blocking buffer for 10 min and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (dilution 1:500, H+L secondary antibody, Chemicon, Millipore, Germany) for 45 nin. Finally, cells were rinsed in PBS and mounted with mounting medium containing Dapi (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, Germany). All steps were performed at room temperature. Fluorescence was observed under a Leica SP confocal microscope.

For the assessment of anti-gp210 antibodies, a Quanta lite™ enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Inova Diagnostics, San Diego CA, Inc) kit was used according to the manufacture’s instructions.

Data are presented as percentages (%) or as mean ± SD, unless otherwise stated. Differences between autoantibody positive and negative patients for various clinical, histological, and serological measurements were compared using multivariate regression analysis. The survival time was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and compared by the Breslow test. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare causes of death between ANEA positive and negative and gp-210 positive and negative patients. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v.15.0 and Excel 2003 software.

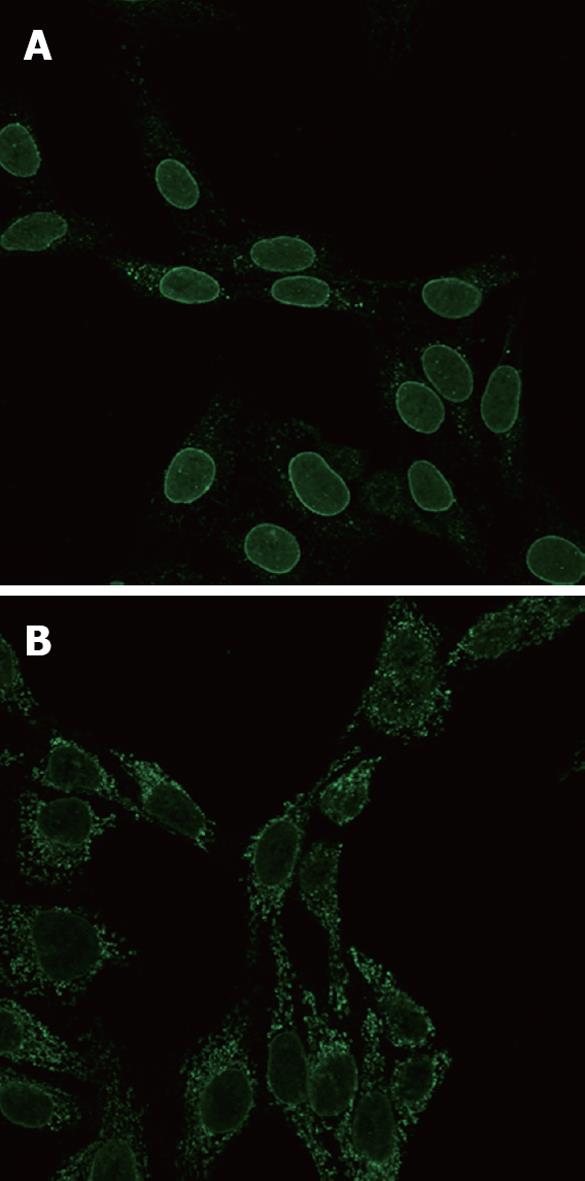

Fixation was important in visualization of ANEA by immunofluorescence, 1% fixation allowed for much better discrimination of antinuclear antibodies (Figure 1).

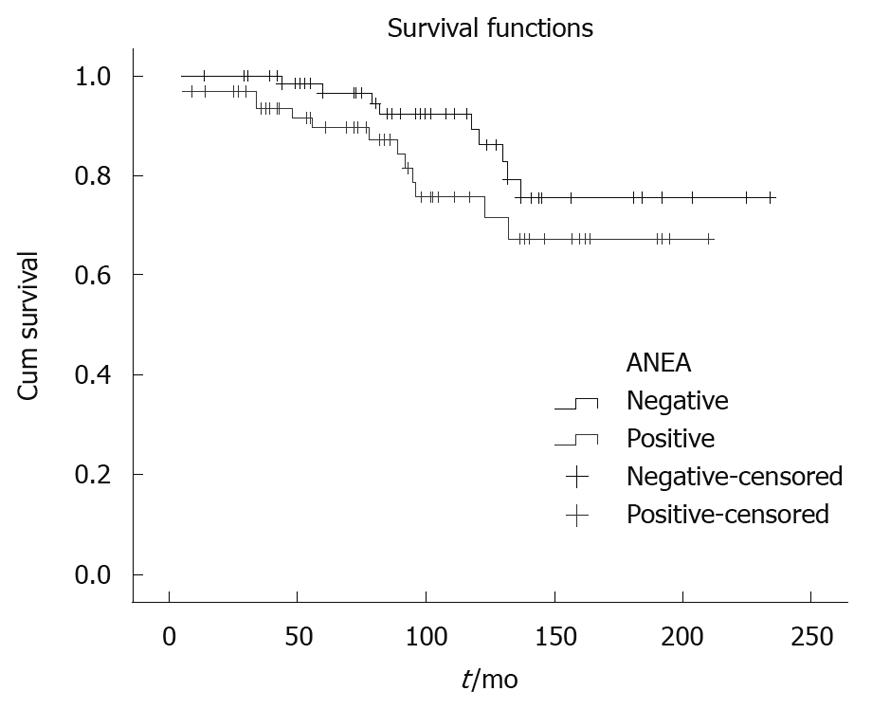

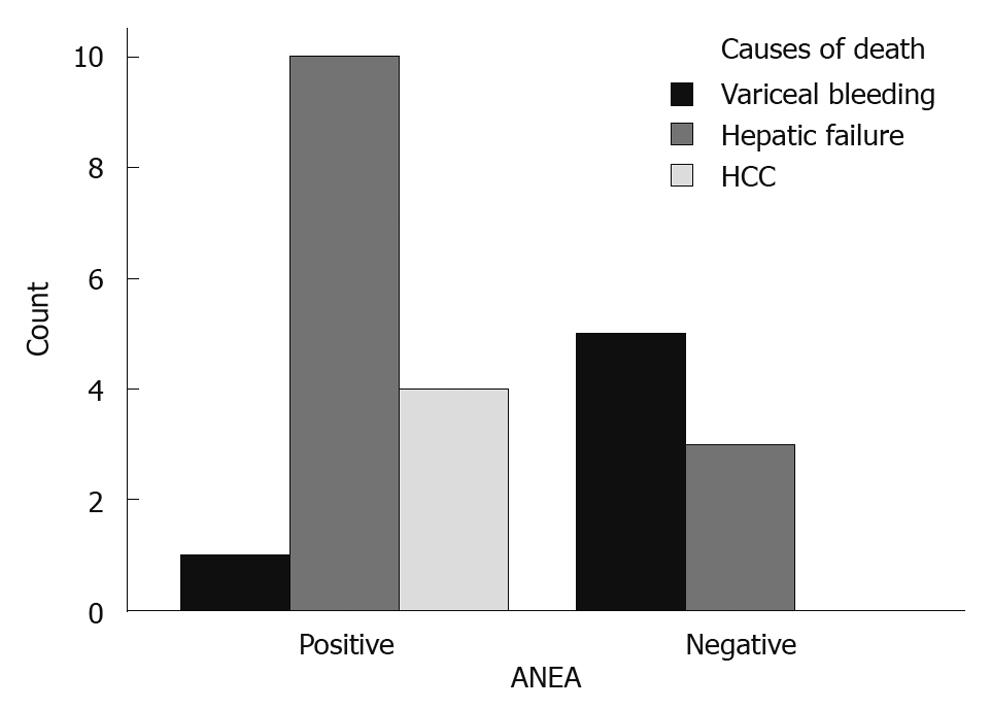

Parameters used in multivariate analysis are shown in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3. The ANEA were detected by IIF on Hep2 cells giving a typical peri-nuclear staining pattern (Figure 1). ANEA were detected in 69 (46.9%) of 147 patients. Comparisons between ANEA positive and negative patients are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Although there was no significant difference in the number of alive/dead between positive and negative ANEA patients [51 (77.3%)/15 (22.7%) vs 66 (86.8%)/10 (13.2%), NS], there was a statistical significance in survival period between the two groups (91.7 ± 50.7 mo vs 101.8 ± 55 mo, P = 0.043) (Table 1 and Figure 2). Moreover, causes of death were significantly different between ANEA positive and negative patients (Figure 3).

| ANEA | P value | ||

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Patients | 69 (46.9) | 78 (53.1) | |

| Age (yr) | 59.3 ± 11.8 | 59.1 ± 10.1 | 0.330 |

| AMA titer ≤ 1:160/> 1:1601 | 35 (50.7)/34 (49.3) | 56 (71.8)/22 (28.2) | 0.001 |

| Stage I-II/stage III-IV | 39 (56.5)/30 (43.5) | 58 (74.4)/20 (25.6) | 0.005 |

| Alive/dead | 51 (77.3)/15 (22.7) | 66 (86.8)/10 (13.2) | 0.162 |

| Survival | 91.7 ± 50.7 | 101.8 ± 55 | 0.043 |

| Mayo risk score | 5.19 ± 1.8 | 5.04 ± 1.3 | 0.239 |

| Histological parameters | P value | ||

| ANEA positive (n = 69) | ANEA negative (n = 78) | ||

| Fibrosis | |||

| 1 | 10 (22.7) | 22 (40.7) | 0.008 |

| 2 | 17 (38.6) | 22 (40.7) | |

| 3 | 17 (38.6) | 10 (18.6) | |

| Portal inflammation | |||

| 1 | 8 (18.2) | 22 (40.7) | 0.008 |

| 2 + 3 | 36 (81.8) | 32 (59.3) | |

| Interface hepatitis | |||

| 0 + 1 | 16 (36.4) | 31 (57.4) | 0.019 |

| 2 + 3 | 28 (63.6) | 23 (42.6) | |

| Intralobular inflammation | |||

| 0 | 11 (25) | 9 (16.7) | 0.359 |

| 1 | 19 (43.2) | 35 (64.8) | |

| 2 | 14 (31.8) | 10 (18.5) | |

| Proliferation of bile ductules | |||

| 0 | 12 (27.3) | 25 (46.3) | 0.027 |

| 1 | 32 (72.7) | 29 (53.7) | |

| Epithelioid granuloma | |||

| 0 | 31 (70.5) | 39 (72.2) | 0.425 |

| 1 | 13 (29.5) | 15 (27.8) | |

| Histological parameters | P value | ||

| Gp210 negative (n = 38) | ANEA negative (n = 78) | ||

| Fibrosis | |||

| 1 | 7 (25.0) | 22 (40.7) | 0.009 |

| 2 | 8 (28.6) | 22 (40.7) | |

| 3 | 13 (48.4) | 10 (18.6) | |

| Portal inflammation | |||

| 1 | 5 (17.9) | 22 (40.7) | 0.018 |

| 2 + 3 | 23 (82.1) | 32 (59.3) | |

| Interface hepatitis | |||

| 0 + 1 | 10 (35.7) | 31 (57.4) | 0.032 |

| 2 + 3 | 18 (64.3) | 23 (42.6) | |

| Intralobular inflammation | |||

| 0 | 8 (28.6) | 9 (16.7) | 0.274 |

| 1 | 14 (50.0) | 35 (64.8) | |

| 2 | 6 (21.4) | 10 (18.5) | |

| Proliferation of bile ductules | |||

| 0 | 7 (25.0) | 25 (46.3) | 0.031 |

| 1 | 21 (75.0) | 29 (53.7) | |

| Epithelioid granuloma | |||

| 0 | 19 (67.9) | 39 (72.2) | 0.342 |

| 1 | 9 (32.1) | 15 (27.8) | |

AMA titers were not associated with disease severity. Kaplan-Meier analysis showed P > 0.7 when AMA titers were examined in relation to patient survival.

We tested all 69 ANEA positive patients (18 dead, five from liver unrelated death) for the anti-gp210 antibodies by ELISA and found 38 (55.1%) negative and 31 (44.9%) positive, representing 21% of all studied patients.

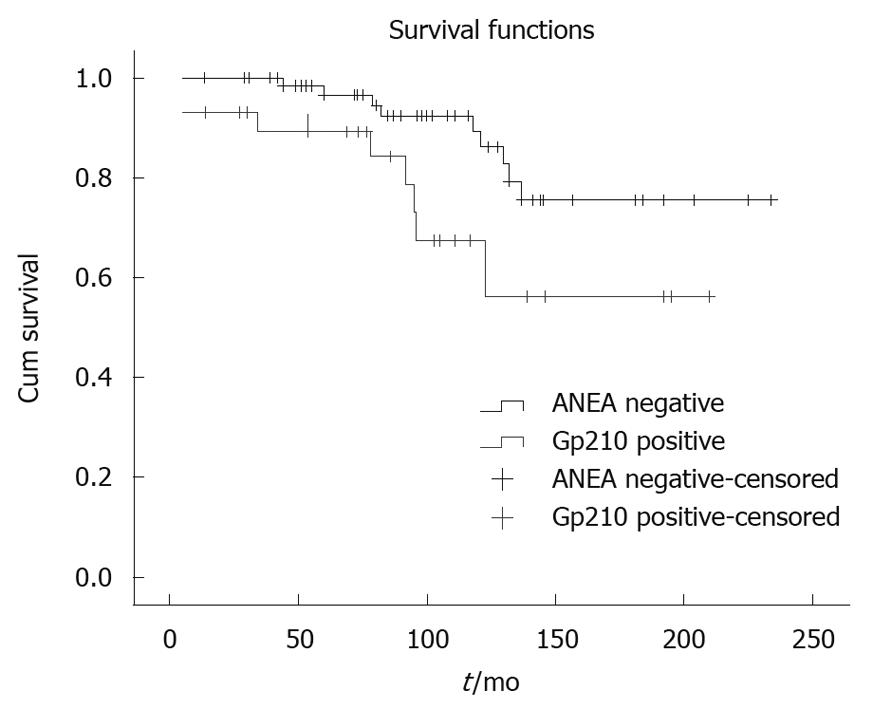

Comparing the anti-gp210 positive patients (n = 31) with the ANEA negative patients (n = 78) we found significantly higher AMA titer (≤ 1:160/> 1:160 51.6%/48.4% vs 71.8%/28.2%, P = 0.009), more late stages (I-II/III-IV 54.8%/45.2% vs 74.4%/25.6%, P = 0.006), higher Mayo risk score (5.5 ± 1.9 vs 5.04 ± 1.3, P = 0.04) and shorter survival period (91.1 ± 52.9 mo vs 101.8 ± 55 mo, P = 0.009) (Figure 4).

Comparing the 38 ANEA positive-gp210 negative patients with the 78 ANEA negative patients, we found that the ANEA negative ones had lower AMA titers (≤ 1:160/> 1:160 50%/50% vs 71.8%/28.2%, P = 0.002), earlier stage (I-II/III-IV 57.9%/42.1% vs 74.4%/25.6%, P = 0.033), less severe fibrosis, portal inflammation, interface hepatitis, and proliferation of bile ductules (P = 0.009, P = 0.018, P = 0.032 and P = 0.031, respectively) (Table 3).

Between anti-gp210 positive (n = 31) and ANEA positive, anti-gp210 negative (n = 38) patients the only parameter that differed was Mayo risk score (5.5 ± 1.9 vs 4.9 ± 1.7, P = 0.038). No difference between the two groups was found for any of the other clinical, demographic, histological parameters or for survival (mean 91.1 ± 52.9 and 92 ± 49.6 mo respectively).

Causes of death were no different between gp-210 positive and negative patients.

In recent years, significant steps have been made in the clarification of the pathogenesis of PBC, although definitive data have not yet been provided[17,18]. Moreover, the mechanisms controlling disease severity and, therefore, prognosis in this clinically heterogeneous disease are still not well established. In recent years, more patients have been diagnosed in at the presymptomatic or asymptomatic stage than before. Some of these patients undergo a benign course and others a more progressive one, with early appearance of symptoms and rapid deterioration, leading to liver transplantation or death[1,19,20].

Prognostic scores based on clinical parameters (Mayo risk score and bilirubin) have been developed in patients with advanced disease, but they have not been validated in presymptomatic or asymptomatic patients.

Earlier studies failed to demonstrate an association of disease severity and progression, with ANEA[21,22]. However in 2001, Invernizzi et al[7] reported an association of antibodies to NPC with disease activity and severity, which was confirmed, in particular for anti-gp210, in Italian PBC patients two years later[23]. In American and Canadian patients, ANEA were associated with increased risk of liver failure[24].

Nakamura et al[4] in 276 Japanese PBC patients reported a prevalence of 26% for anti-gp210. In that study, anti-gp210 presence correlated with survival and a hepatic failure pattern of disease progression. By contrast, in a cohort of 170 Spanish and 162 Greek patients, only 10.4% of patients were anti-gp210 positive. In that study, there was no correlation with survival or histological severity, although correlations with Mayo risk score, ALP, and bilirubin were reported[15]. The authors stated that the low prevalence could be an ethnic or geographic variation and that, although anti-gp210 represents a disease severity marker, it is not a prognostic one. However, our results of anti-gp210 prevalence, using the same ELISA kits, in a homogeneous Greek population from the island of Crete, are similar to the Japanese report.

Similarly to the Japanese report, our ANEA positive patients died more frequently of hepatic failure and/or hepatocellular carcinoma, while ANEA negative patients died more frequently as a result of variceal bleeding.

Indeed, we found that 46.9% of the patients were ANEA positive and 21% anti-gp210 positive, a similar percentage to the Japanese patients (26%). The ANEA positive patients at the time of diagnosis were at later histological stages, with more severe fibrosis, portal inflammation, bile ductular proliferation, and interface hepatitis. They had higher AMA titers and, as expected, shorter survival periods than the ANEA negative patients. The anti-gp210 positive patients differed from the rest of the ANEA positive patients only in their higher Mayo risk scores. It should be noted that, with the usual 4% formaldehyde fixation used with Hep2 cells, there might be a difficulty in discrimination between peri-nuclear and cytoplasmic fluorescence caused by the presence of high titers of antimitochondrial antibodies. By contrast, our slight modification using 1% fixation instead allowed for much better visualization of peri-nuclear staining; therefore, we strongly recommend this fixation for further use.

In conclusion, our data confirm that, in Greek PBC patients, there is a correlation between the presence of ANEA antibodies and disease severity and shorter survival. The presence of anti-gp210 seems to be an additional factor, reducing survival. Therefore, we suggest that presence of ANEA and anti-gp210 should be routinely checked, because their presence identifies a subgroup of PBC patients with poor prognosis. The mechanism underlying the association of ANEA with prognosis requires further elucidation.

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is an autoimmune disease of unknown etiology, where genetic and environmental factors have roles in disease pathogenesis. The clinical course of the disease is variable, and no specific serological markers can predict disease progression. Peri-nuclear antibodies have not been adequately evaluated as predictive markers and the results so far are contradictory.

Peri-nuclear antibodies were evaluated using a modification of the immunofluorescent identification technique, which allows for better visualization of these antibodies and avoids a possible confusion with antimitochondrial antibodies. The presence of anti-nuclear envelope antibody (ANEA), was associated with decreased patient survival and causes of death.

The modified technique might explain the reported differences with other European patient cohorts. Moreover, the patient population in this study is racially homogeneous, thus excluding possible racial differences as a factor of genetic influence in the results.

The findings of the present study suggest that identification of the presence of ANEA should be included in the routine work up of patients with PBC, because they identify a subgroup with worse prognosis, for whom a more intense follow up scheme should be applied.

In this manuscript, the authors describe the apparent association between antinuclear antibodies, especially ANEA, and the severity and survival of 147 patients with PBC in a single-center cohort in Greek. They examined ANEA and anti-gp210 antibodies in sera at diagnosis and found that ANEA positivity, as well as anti-gp210 positivity, could identify a subgroup of PBC patients with poor prognosis. These results are coincident with previous results from Japan and look very interesting.

Peer reviewers: Atsushi Tanaka, MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Teikyo University School of Medicine, 2-11-1, Kaga, Itabashi-ku, Tokyo 173-8605, Japan; Satoshi Yamagiwa, MD, PhD, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Niigata University Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, 757 Asahimachi-dori, Chuo-ku, Niigata 951-8510, Japan

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Stewart GJ E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Kumagi T, Heathcote EJ. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3:1. |

| 2. | Liu B, Shi XH, Zhang FC, Zhang W, Gao LX. Antimitochondrial antibody-negative primary biliary cirrhosis: a subset of primary biliary cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2008;28:233-239. |

| 3. | He XS, Ansari AA, Ridgway WM, Coppel RL, Gershwin ME. New insights to the immunopathology and autoimmune responses in primary biliary cirrhosis. Cell Immunol. 2006;239:1-13. |

| 4. | Nakamura M, Kondo H, Mori T, Komori A, Matsuyama M, Ito M, Takii Y, Koyabu M, Yokoyama T, Migita K. Anti-gp210 and anti-centromere antibodies are different risk factors for the progression of primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;45:118-127. |

| 5. | Palmer JM, Doshi M, Kirby JA, Yeaman SJ, Bassendine MF, Jones DE. Secretory autoantibodies in primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC). Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;122:423-428. |

| 6. | Rigopoulou EI, Davies ET, Pares A, Zachou K, Liaskos C, Bogdanos DP, Rodes J, Dalekos GN, Vergani D. Prevalence and clinical significance of isotype specific antinuclear antibodies in primary biliary cirrhosis. Gut. 2005;54:528-532. |

| 7. | Invernizzi P, Podda M, Battezzati PM, Crosignani A, Zuin M, Hitchman E, Maggioni M, Meroni PL, Penner E, Wesierska-Gadek J. Autoantibodies against nuclear pore complexes are associated with more active and severe liver disease in primary biliary cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2001;34:366-372. |

| 8. | Wesierska-Gadek J, Klima A, Ranftler C, Komina O, Hanover J, Invernizzi P, Penner E. Characterization of the antibodies to p62 nucleoporin in primary biliary cirrhosis using human recombinant antigen. J Cell Biochem. 2008;104:27-37. |

| 9. | Courvalin JC, Lassoued K, Worman HJ, Blobel G. Identification and characterization of autoantibodies against the nuclear envelope lamin B receptor from patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Exp Med. 1990;172:961-967. |

| 10. | Lin F, Noyer CM, Ye Q, Courvalin JC, Worman HJ. Autoantibodies from patients with primary biliary cirrhosis recognize a region within the nucleoplasmic domain of inner nuclear membrane protein LBR. Hepatology. 1996;23:57-61. |

| 11. | Worman HJ, Courvalin JC. Antinuclear antibodies specific for primary biliary cirrhosis. Autoimmun Rev. 2003;2:211-217. |

| 12. | Züchner D, Sternsdorf T, Szostecki C, Heathcote EJ, Cauch-Dudek K, Will H. Prevalence, kinetics, and therapeutic modulation of autoantibodies against Sp100 and promyelocytic leukemia protein in a large cohort of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1997;26:1123-1130. |

| 13. | Wesierska-Gadek J, Penner E, Battezzati PM, Selmi C, Zuin M, Hitchman E, Worman HJ, Gershwin ME, Podda M, Invernizzi P. Correlation of initial autoantibody profile and clinical outcome in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2006;43:1135-1144. |

| 14. | Nakamura M, Shimizu-Yoshida Y, Takii Y, Komori A, Yokoyama T, Ueki T, Daikoku M, Yano K, Matsumoto T, Migita K. Antibody titer to gp210-C terminal peptide as a clinical parameter for monitoring primary biliary cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2005;42:386-392. |

| 15. | Bogdanos DP, Liaskos C, Pares A, Norman G, Rigopoulou EI, Caballeria L, Dalekos GN, Rodes J, Vergani D. Anti-gp210 antibody mirrors disease severity in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;45:1583-1584. |

| 16. | Tsiakalou V, Tsangaridou E, Polioudaki H, Nifli AP, Koulentaki M, Akoumianaki T, Kouroumalis E, Castanas E, Theodoropoulos PA. Optimized detection of circulating anti-nuclear envelope autoantibodies by immunofluorescence. BMC Immunol. 2006;7:20. |

| 17. | Kouroumalis E, Notas G. Pathogenesis of primary biliary cirrhosis: a unifying model. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2320-2327. |

| 18. | Selmi C, Zuin M, Gershwin ME. The unfinished business of primary biliary cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2008;49:451-460. |

| 19. | Jones DE, James OF, Bassendine MF. Primary biliary cirrhosis: clinical and associated autoimmune features and natural history. Clin Liver Dis. 1998;2:265-282, viii. |

| 20. | Springer J, Cauch-Dudek K, O’Rourke K, Wanless IR, Heathcote EJ. Asymptomatic primary biliary cirrhosis: a study of its natural history and prognosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:47-53. |

| 21. | Lassoued K, Brenard R, Degos F, Courvalin JC, Andre C, Danon F, Brouet JC, Zine-el-Abidine Y, Degott C, Zafrani S. Antinuclear antibodies directed to a 200-kilodalton polypeptide of the nuclear envelope in primary biliary cirrhosis. A clinical and immunological study of a series of 150 patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:181-186. |

| 22. | Nickowitz RE, Wozniak RW, Schaffner F, Worman HJ. Autoantibodies against integral membrane proteins of the nuclear envelope in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:193-199. |

| 23. | Muratori P, Muratori L, Ferrari R, Cassani F, Bianchi G, Lenzi M, Rodrigo L, Linares A, Fuentes D, Bianchi FB. Characterization and clinical impact of antinuclear antibodies in primary biliary cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:431-437. |

| 24. | Yang WH, Yu JH, Nakajima A, Neuberg D, Lindor K, Bloch DB. Do antinuclear antibodies in primary biliary cirrhosis patients identify increased risk for liver failure? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:1116-1122. |