CASE REPORT

In November 2008, a 40-year-old man was referred to our hospital due to febrile episodes and abnormal liver tests that developed during the previous month. Initial liver function tests indicated cholestasis without hyperbilirubinemia [alkaline phosphatase (AP) 1030 IU/L, γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) 419 U/L and total bilirubin 14 μmol/L] with an increased level of transaminase activity [aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 170 IU/L and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 156 IU/L]. A 5-d treatment of amoxicillin-clavulanate for Klebsiella pneumonia urinary infection, preceding the symptoms, was promptly discontinued with no improvement in liver tests. The initial physical examination was unremarkable. Abdominal ultrasound (US) revealed a slightly hyperechogenic liver without focal lesions and normal biliary system. Serology (hepatitis A, B, C, human immunodeficiency virus, Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus), autoimmune studies (antinuclear, antimitochondrial, anti-smooth muscle and anti-liver-kidney microsomal antibodies) and tumor markers (α-fetoprotein, carbohydrate antigen 19-9 and prostate-specific antigen) tested negative. There was no history of intravenous drugs or hepatotoxic substances abuse.

On admission, functional liver tests showed slight progression of cholestatic pattern: AP 1511 IU/L, GGT 516 U/L, total bilirubin 17 μmol/L, AST 200 IU/L and ALT 197 IU/L. Repeat physical examination revealed moderate hepatosplenomegaly with no peripheral lymphadenopathy. Abdominal US showed an enlarged, hyperechogenic liver without focal lesions and an enlarged spleen. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed the aforementioned finding with additional slightly enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Chest CT scan was normal.

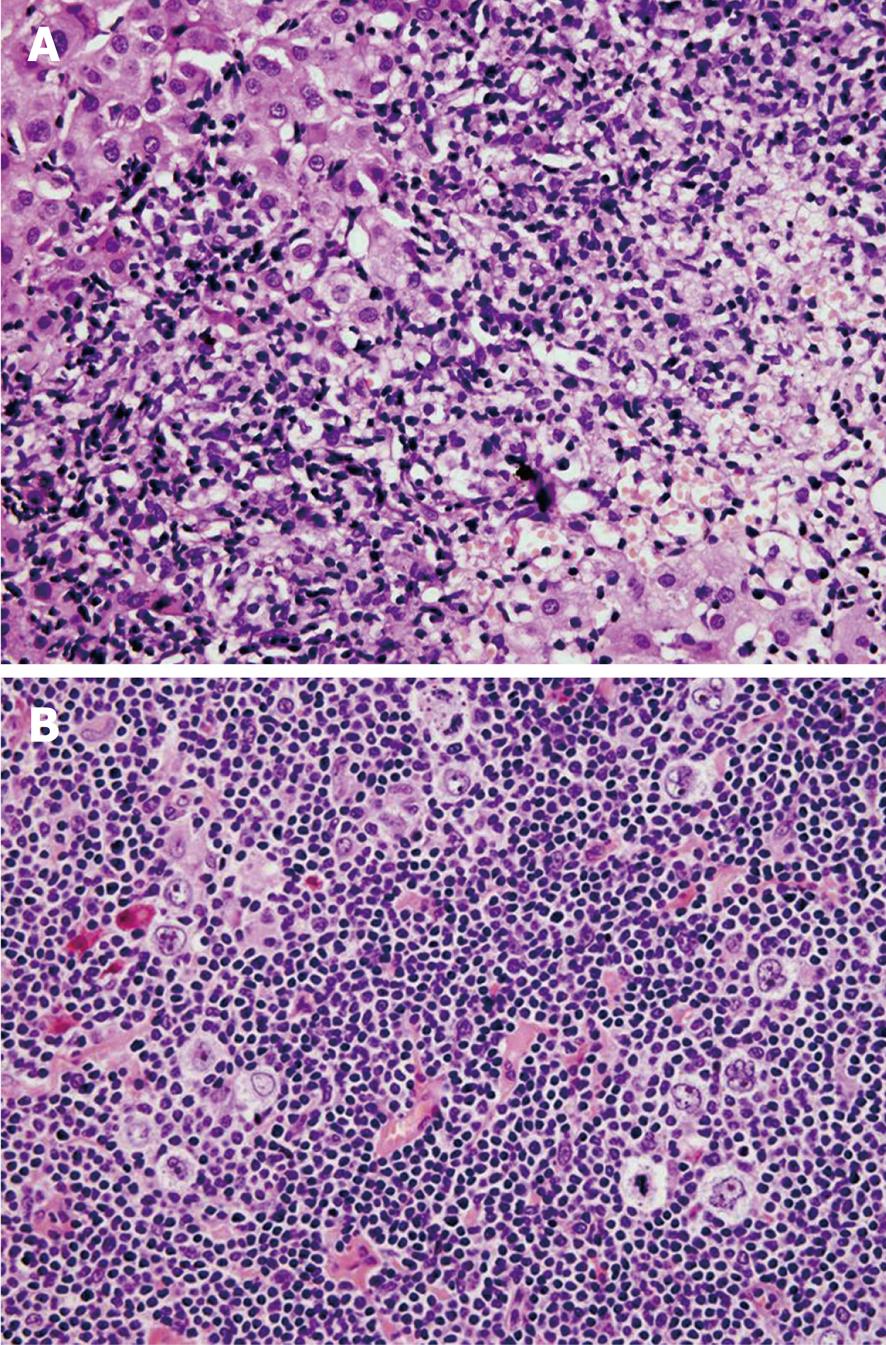

Three months after initial symptoms, liver biopsy showed portal areas filled with mixed inflammatory infiltrate, containing lymphocytes, histiocytes, and rare atypical lymphatic cells with large nuclei (CD20+, CD45+). In addition to mild interface hepatitis, there were also signs of mild canalicular and cytoplasmic cholestasis (Figure 1A).

Figure 1 Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma of the liver and axillary lymph node.

A: A portal tract showing a dense lymphoid infiltrate. The multiple sections revealed just a few scattered, CD20 positive neoplastic cells (HE stain, × 40); B: The popcorn (Hodgkin lymphoma) cells with the typically lobulated nuclei in a background of small lymphoid cells (HE stain, × 40).

US of the neck, inguinal and axillary region showed a single enlarged (2 cm) left axillary lymph node. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) of the lymph node was suggestive for HL. An extirpated axillary lymph node showed a pseudonodular pattern with expanded follicular dendritic network (highlighted with CD23 antibody), and scattered atypical “popcorn” cells (LP cells) that stained positively for CD20, CD45, PAX5 and EMA, and negatively for CD30, CD15, and EBV-LMP (Figure 1B) reconfirming the diagnosis of nodular lymphocytic predominant HL. No bone marrow infiltration was found.

The final diagnosis was advanced NLPHL (clinical stage IVB) and the initial treatment consisted of four cycles of the ABVD protocol (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine). Evaluation after treatment showed no B-symptoms or signs of peripheral adenopathy, but hepatosplenomegaly and abdominal lymphadenopathy persisted. Disease activity was confirmed by liver FNA and treatment was continued with the bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine and prednisone (BEACOPP) protocol. On the ninth day of the new protocol the patient died due to sepsis. Postmortem liver specimen revealed scanty lymphatic portal infiltrate without LP cells.

DISCUSSION

In this case report, the diagnosis of HL was established by a liver biopsy identifying a rare subtype of HL, NLPHL. The clinical and laboratory characteristics were consistent with febrile cholestatic disease with the exclusion of other possible causes such as biliary tract obstruction, bacterial and viral infections, autoimmune disease or hepatotoxic substances.

NLPHL is a rare subtype of HL (representing 5% of HL) with unique clinicopathologic features and an indolent clinical course[4]. The major pathohistological feature is the presence of malignant LP cells, variants of Reed-Sternberg cells (CD20+CD15-CD30-) within a nodular pattern of infiltrating lymphocytes. Although initial presentation of NLPHL is peripheral lymphadenopathy in some rare cases, other sites may also be involved (spleen, liver, lung and bone marrow)[5-10].

Febrile cholestatic liver disease as a first symptom is an extremely unusual presentation of HL. In the only published series of 421 HL patients, 1.4% of patients initially had cholestasis and fever with no peripheral adenopathies[1]. Liver involvement of any kind at the time of presentation of HL is infrequent and ranges from 5-14%, but increases with advanced stages of the disease up to 60% postmortem[3].

Cholestasis in HL can be the result of parenchymal infiltration by the tumor, biliary tract obstruction secondary to extrahepatic lymphoma or paraneoplastic phenomenon[11]. Parenchymal involvement is the most common mechanism of cholestasis and may consist of diffuse or focal infiltrates, portal zone cellularity, an epithelioid cell reaction or as lymphoid aggregates[12]. Cholestasis secondary to biliary tract obstruction is rare with a frequency of 0.5%[13]. The most rarely seen mechanism of cholestasis is the paraneoplastic phenomenon in the form of HL-related idiopathic cholestasis (IC) and vanishing bile duct syndrome (VBDS). It remains controversial as to whether HL-related IC and VBDS represent different pathohistological entities or a spectrum of the same disease. The exact mechanism of ductal destruction and cholestasis is unclear, but it is hypothesized that cytotoxic T lymphocytes or toxic cytokines from lymphoma cells are responsible for ductopenia[14].

In the presented case, the mechanism of liver injury was parenchymal infiltration by tumor, manifested as cholestasis without hyperbilirubinemia and increased transaminase activity. Liver involvement is a rare initial presentation of NLPHL (2%-3%) but may lead to fulminant liver failure as recently described[15].

Moreover, liver involvement is more frequent in aggressive types of HL such as mixed cellularity and lymphocytic depletion[2]. The prognosis for patients with liver disease as the initial manifestation of HL is generally poor[1,15-17], but not the rule, since some case reports show favorable response to chemotherapy[18-22]. Unfortunately, this was not the case with our patient where 3 mo after the appearance of symptoms, ABVD chemotherapy resulted in a poor therapeutic response. After the first cycle of the more aggressive BEACOPP therapy, the anti-lymphoma effect was sufficient, but toxicity led to a fatal outcome.

HL should be considered in the differential diagnosis of cholestasis. Due to limitations in laboratory and morphological investigations, liver biopsy should be considered in the early phase of the diagnostic algorithm to confirm the diagnosis and enable appropriate treatment.