INTRODUCTION

It is estimated that 10% of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients in the United States and Europe are chronically coinfected with hepatitis B virus (HBV)[1,2]. In other regions, rates of HBV coinfection in HIV-infected patients may be even higher[3]. HIV-HBV coinfected patients have higher rates of liver-related morbidity and mortality compared to patients infected with either virus alone[4,5]. Therefore, current guidelines suggest that HIV-infected patients with HBV infection should be treated with a highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) regimen that is also active against HBV[6]. However, HIV-HBV coinfected patients are particularly susceptible to certain complications of HAART. The vast majority of antiretroviral medications have been associated with some degree of hepatotoxicity and the presence of HBV infection is an independent risk factor for the development of clinically significant hepatotoxicity[7-9]. Additionally, coinfected patients are at risk for HBV immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), which is characterized by a paradoxical hepatitis flare corresponding to an initial improvement in plasma HIV RNA level and CD4+ T-cell count on HAART[10]. Overall, liver enzyme elevations in HIV-HBV coinfected patients after starting HAART are not uncommon, but acute liver failure (ALF) is rare[11]. Reported cases have typically involved treatment with older thymidine analogue drugs such as stavudine and didanosine[12]. We describe two cases in which fatal ALF occurred in patients with HIV-HBV coinfection after beginning HAART regimens which did not include thymidine analogues but which did have activity against HBV.

CASE REPORT

Patient A

A 42-year-old African-American male with longstanding HIV/HBV coinfection was seen in clinic. He had been diagnosed with HIV infection over 10 years previously but had been on antiretrovirals for only short periods since diagnosis. As a result, his CD4+ T-cell count had reached a nadir of 5 cells/μL (1%) with a plasma HIV RNA level of 51 230 copies/mL. His plasma HBV DNA level was 147 million IU/mL. Both hepatitis B endogenous antigen (HBeAg) and anti-HBe antibody were negative. He was started on a new regimen of ritonavir-boosted atazanavir, lamivudine, and abacavir. At that time, his alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were both slightly elevated at 94 U/L (normal range 17-63 U/L) and 73 U/L (normal range 10-42 U/L), respectively, with a normal bilirubin level. The patient had never undergone a liver biopsy. Eight weeks after starting therapy, he returned to clinic with nausea, vomiting, and jaundice. The ALT level had increased to 1352 U/L and the AST was 1765 U/L. Total bilirubin was 14.1 mg/dL, direct bilirubin was 8.9 mg/dL, and prothrombin time was 18.9 s (INR 1.62). HIV RNA level had decreased to 100 copies/mL. He was admitted to the hospital for further workup. The patient did not drink alcohol and acetaminophen level was undetectable. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA was undetectable, hepatitis D virus (HDV) antibody was negative, and hepatitis A virus (HAV) IgM was negative. HBV DNA had decreased to 4.42 million IU/mL. Anti-nuclear antibody screen was negative. All medications were held for 48 h. His ALT and AST levels decreased to 992 U/L and 1505 U/L. The appearance of the liver was normal on computed tomography of the abdomen with no suggestion of cirrhosis or portal hypertension. He was then discharged after starting a new regimen of ritonavir-boosted fosamprenavir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir. Ten days later he was re-admitted to the hospital with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. ALT and AST levels had risen to 1214 U/L and 1992 U/L. Total bilirubin was 29.5 mg/dL, direct bilirubin was 18.3 mg/dL, and prothrombin time was 35.4 s (INR 3.19). HBV DNA level had decreased to 83 100 IU/mL. The ritonavir and fosamprenavir were discontinued and he was continued on emtricitabine/tenofovir. A liver biopsy showed marked septal fibrosis with nodule formation that was consistent with cirrhosis (Figure 1A and B). There was a severe mixed inflammatory infiltrate in portal and periportal areas containing lymphocytes, plasma cells and scant eosinophils (Figure 2A). The liver eosinophils were readily identified and no other special stains such as sirius red were used. Peripheral blood eosinophil count was within normal limits. Severe piecemeal necrosis was present diffusely around most of the portal tracts linking some of them together in so-called bridging necrosis (Figure 2B). After 10 d, his ALT and AST levels had come down to 405 U/L and 758 U/L, but total and direct bilirubin remained elevated at 28.8 mg/dL and 13.6 mg/dL. Due to concern for creating HIV resistance, he was switched from emtricitabine/tenofovir to adefovir. After 1 wk, he developed worsening renal failure and was switched from adefovir to emtricitabine and telbivudine. However, his condition continued to deteriorate. After 3 wk in the hospital, he became progressively encephalopathic, thrombocytopenic with a platelet count of 33 000/μL, and coagulopathic with prothrombin time of 37.7 s (INR 3.41). He developed hematemesis and became increasingly unresponsive with an ammonia level of 96 μmol/L (normal range 11-35 μmol/L). The patient was thought to be too unstable to undergo liver transplantation. After discussions with his family, he was placed on comfort care and died.

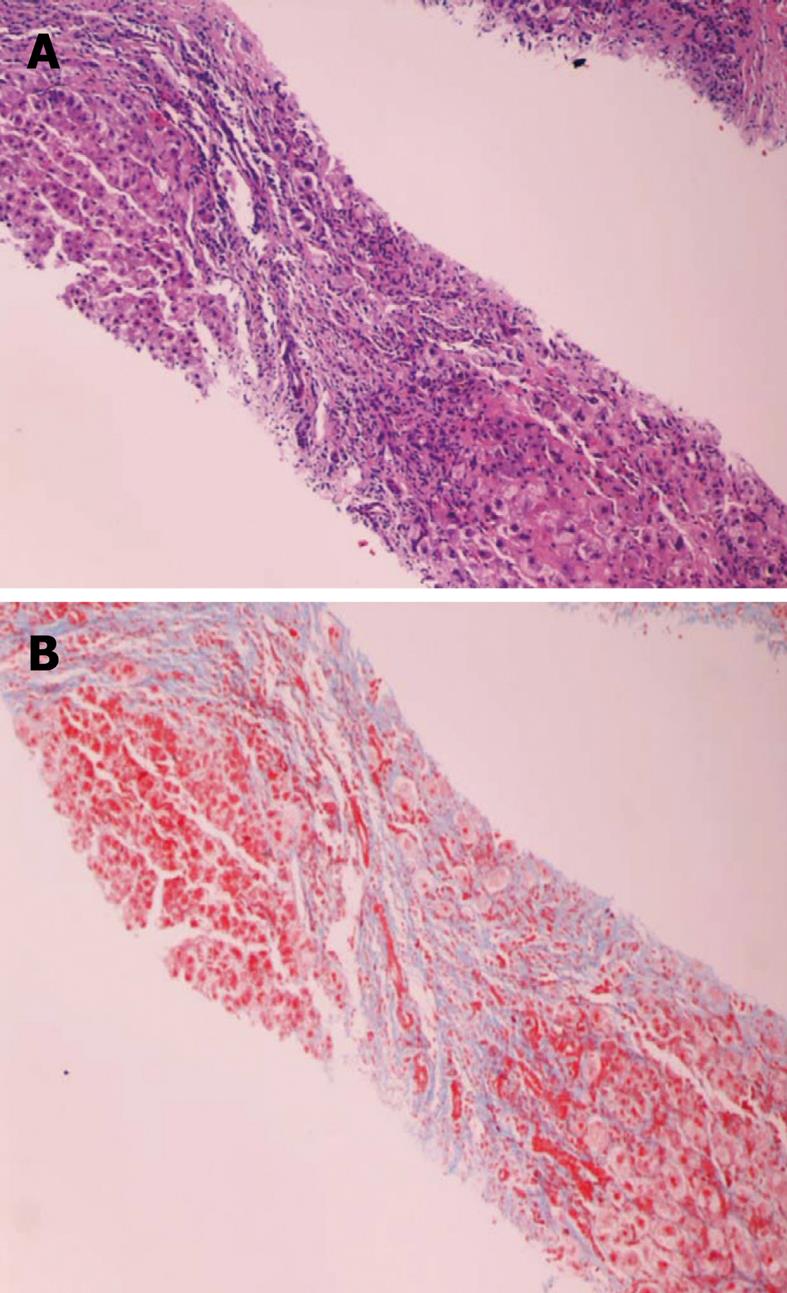

Figure 1 Liver biopsy, low power magnification (100 ×).

A: Hematoxylin and eosin stain showing a low power view of two cirrhotic nodule surrounded by fibrosis. The edges of the nodules and the fibrous septi contain intense chronic inflammatory infiltrate; B: Trichrome stain delineating fibrous septa that surround liver nodules in blue color.

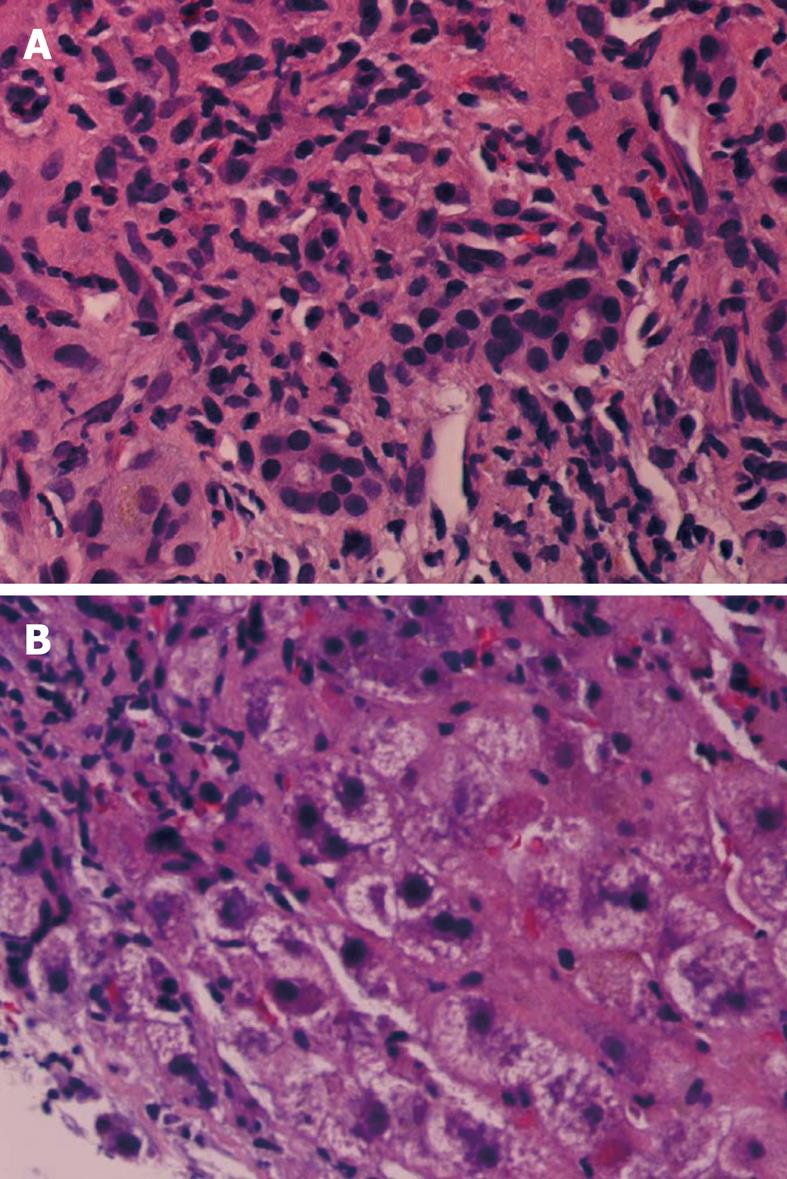

Figure 2 Liver biopsy, high power magnification (hematoxylin and eosin stain, 600 ×).

A: Marked portal inflammatory infiltrate composed of plasma cells and a few eosinophils; B: High power view of a cirrhotic nodule composed of markedly swollen hepatocytes, some with granular eosinophilic cytoplasm and intense inflammatory infiltrate at the interface between parenchyma and fibrosis.

Patient B

A 46-year-old African-American male came to clinic with a new diagnosis of HIV infection. CD4+ T-cell count was 44 cells/μL (8%) with a plasma HIV RNA level of 9620 copies/mL. He was also diagnosed with hepatitis B infection with HBV DNA level > 500 million IU/mL. Duration of HBV infection was not known but HBV core IgM was negative. HCV antibody was negative, HBeAg was negative, anti-HBe antibody was positive, and HDV antibody was negative. ALT level was normal at 62 U/L and AST was slightly elevated at 53 U/L. He was started on a regimen of once daily ritonavir-boosted darunavir and tenofovir/emtricitabine. Five weeks after starting this regimen, he presented with nausea, vomiting, and jaundice. ALT was 1195 U/L and AST was 1396 U/L. Total bilirubin was 13.5 mg/dL, direct bilirubin was 7.7 mg/dL, and prothrombin time was 27.4 s (INR 2.42). HBV DNA level had decreased to 342 000 IU/mL. HIV RNA level was undetectable at < 50 copies/mL and CD4+ T-cell count was 52 cells/μL (10%). HAV IgM was negative and HCV antibody was negative on recheck. Both serum ethanol and acetaminophen levels were undetectable. The patient reported no sexual activity for over 1 year and he never used injectable drugs. Magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen showed fibrotic changes throughout the liver and portal hypertension evidenced by splenomegaly, a recanalized umbilical vein and minimal perigastric and perisplenic varices. After all medications were held for 72 h, he was restarted on a regimen of ritonavir-boosted fosamprenavir and tenofovir/emtricitabine. Over the next week, his ALT and AST levels trended down to 803 U/L and 773 U/L and his platelets remained within normal limits. However, over that period of time his prothrombin time increased to 42.5 s (INR 3.88) and he became profoundly encephalopathic with an ammonia level of 137 μmol/L. The patient was thought to be too unstable for liver transplantation. After a total of 10 d in the hospital he developed cardiac arrest and died.

DISCUSSION

The development of elevated liver enzymes is not uncommon in HIV-HBV coinfected patients after starting HAART[13]. In the majority of cases, these elevations are mild and do not require modification of treatment[11]. The development of more severe hepatotoxicity (liver enzymes > 10 times the upper limit of normal) is not common and ALF is rare[9]. Among HIV-infected patients in general, those who develop ALF while on HAART have experienced very high rates of mortality[14]. Therefore, an HIV-HBV coinfected patient who develops ALF after starting HAART may be at particularly high risk for mortality, given the presence of underlying liver disease and potentially impaired reserve.

The most appropriate management of such patients is not completely clear, and the optimal management of HIV-HBV coinfected patients who develop liver enzymes > 10 times the upper limit of normal after starting HAART but who do not have evidence of decompensated liver disease may be even more difficult to delineate. One question is whether it is possible to determine if the hepatic injury is from drug toxicity or HBV IRIS and whether this changes management of the patient. Liver biopsy may be helpful in identifying an opportunistic infection, such as mycobacterial disease or cytomegalovirus, that may contribute to liver disease. Liver biopsy may also indicate the presence of cirrhosis. The latter was present in the case of patient A and would have also been found in the case of patient B given radiographic findings. In patient A, liver biopsy showed severe inflammation with lymphocytes, plasma cells, and scant eosinophils. Many cases of HAART-induced ALF in patients without HBV show only mild hepatic inflammatory cell infiltration on biopsy[15]. However, the presence of portal plasma-lymphocytic infiltrate is nonspecific and can be found in chronic viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis and even some medication reactions[16]. The presence of eosinophils may be more specific for a drug reaction[17], though these were scant in this case. Overall, distinguishing between HBV IRIS and drug hepatotoxicity in such cases of ALF may not change management, particularly because it is not clear if anti-inflammatory medications such as corticosteroids are beneficial in HBV IRIS. Corticosteroids have been found to increase HBV replication[18] and this has led some to recommend against the use of corticosteroids in the setting of HBV IRIS[19].

The patients in our series met criteria for ALF according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guideline for liver failure[20]. In this guideline, it is recommended that “all non-essential medications” be discontinued in patients with ALF. Due to the fact that the majority of antiretrovirals, including protease inhibitors[8], have been associated with hepatotoxicity, it is advisable to hold HAART at least in the short term. However, HBV flares have been associated with the discontinuation of HAART regimens that contain anti-HBV activity[21]. This theoretically could contribute to ALF. At the same time, continuing single or dual therapy with anti-HBV agents such as lamivudine or tenofovir would create an environment in which HIV resistance might develop. This has led some to recommend stopping HAART and considering treatment of HBV with agents that do not have activity against HIV in cases of significant hepatitis flares on HAART in the setting of hepatitis B cirrhosis[22]. Adefovir is an option, but this drug has less potency against HBV than other agents[23]. Interferon α-based therapies might be considered, but are contraindicated in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Entecavir was initially thought to have no significant anti-HIV activity, but has subsequently been shown to be associated with the development of HIV resistance mutations when used in the absence of other antiretrovirals[24]. One report suggests that telbivudine may also have activity against HIV[25]. Overall, we believe that the effort to help the patient survive an episode of ALF overrides the preservation of one particular antiretroviral class for future use and that at least one agent with anti-HBV activity should be given in such a scenario. In general, it appears that patients who develop liver failure on HAART, whether coinfected with HBV or not, have a very poor prognosis. These patients should be considered for liver transplantation evaluation, as emerging data show that HIV-HBV coinfected patients have excellent outcomes with liver transplantation[26].

It is prudent to closely monitor the clinical status and liver enzymes of HIV-HBV infected patients after initiation of HAART in order to identify cases of hepatotoxicity early on. Additionally, two new antiretroviral classes have been introduced in recent years. These include the integrase inhibitor class currently represented by raltegravir and the CCR5 antagonist class currently represented by maraviroc. Based on published reports to date, these new agents appear to have minimal hepatotoxicity[27]. While they have only been available since 2007 and toxicities have yet to be fully described, these agents hold promise for HIV-infected patients with chronic liver diseases such as HBV. Perhaps most importantly, efforts should be made to prevent the acquisition of chronic HBV infection, and the HBV vaccine is recommended for all patients with HIV infection[28].