Published online Aug 21, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i31.3979

Revised: May 27, 2010

Accepted: June 3, 2010

Published online: August 21, 2010

AIM: To evaluate the dual-graft living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) with ultrasonography, with special emphasis on the postoperative complications.

METHODS: From January 2002 to August 2007, 110 adult-to-adult LDLTs were performed in West China Hospital of Sichuan University. Among them, dual-graft implantations were performed in six patients. Sonographic findings of the patients were retrospectively reviewed.

RESULTS: All the six recipients survived the dual-graft adult-to-adult LDLT surgery. All had pleural effusion. Four patients had episodes of postoperative abdominal complications, including fluid collection between the grafts in three patients, intrahepatic biliary dilatation in two, hepatofugal portal flow of the left lobe in two, and atrophy of the left lobe in one.

CONCLUSION: Although dual-graft LDLT takes more efforts and is technically complicated, it is safely feasible. Postoperative sonographic monitoring of the recipient is important.

- Citation: Lu Q, Wu H, Yan LN, Chen ZY, Fan YT, Luo Y. Living donor liver transplantation using dual grafts: Ultrasonographic evaluation. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(31): 3979-3983

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i31/3979.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i31.3979

Adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation (A-ALDLT) inevitably implies two potential risks including a small-for-size (SFS) graft for the recipient and a small remnant liver for the donor[1]. Problems related to SFS graft and small remnant livers have gradually come to light with the expansion of A-ALDLT[2-4]. The transplantation of SFS grafts may cause an imbalance between hepatic volume and demand of liver function, which may lead to a severe graft dysfunction known as small-for-size syndrome (SFSS)[5]. To overcome this problem and minimize the overall risk of the family, as an alternative, dual grafts from two living donors into one recipient can make up for graft size insufficiency and secure the recipient and donors’ safety. Because of the complexity of this procedure, intensive postoperative monitoring of the recipient is required. To our knowledge, there have been few reports about the sonographic findings of dual-graft A-ALDLT. Therefore, in this study we describe our experience of sonographic evaluation of A-ALDLT using dual grafts.

From January 2002 to August 2007, 110 A-ALDLTs were performed in West China Hospital of Sichuan University. Among them, dual-graft implantations were performed in 6 male patients (aged 28-42 years, mean 34.7 years). Clinical data of the recipients is shown in Table 1.

| No. | Gender/age (yr) | Diseases | Child-Pugh classification | Body weight (kg) | SLV (mL) |

| 1 | M/35 | Hepatitis B-related cirrhosis, portal hypertension | C | 70 | 1334 |

| 2 | M/37 | Hepatitis B cirrhosis with hepatocellular carcinoma | A | 58 | 1187 |

| 3 | M/42 | Hepatitis-related cirrhosis, portal hypertension | C | 75 | 1037 |

| 4 | M/34 | Hepatitis B-related cirrhosis, portal hypertension | C | 71 | 1310 |

| 5 | M/38 | Hepatitis C cirrhosis with hepatocellular carcinoma | C | 65 | 1210 |

| 61 | M/28 | Hepatitis B cirrhosis with hepatocellular carcinoma | C | 59 | 1290 |

This study was conducted under the approval of the Ethics Committee of our hospital. All donors volunteered to donate their livers. Based on the previous experience, graft recipient weight ratio (GRWR) should be 0.8% or greater to achieve a graft and patient survival of 90%[6]. If GRWR is less than 0.8%, dual grafts should be considered. Furthermore, if macrosteatosis of the liver ranged from 10% to 30% and the grafts with a GRWR less than 1.0%, dual-graft liver transplantation should also be taken into account. Donor candidates who have diabetes, hypertension, or any other significant medical diseases were excluded from the right lobe donation. In order to ensure the safety of the donor, the middle hepatic vein was not harvested in the right lobe graft, and the remnant liver volume was more than 35%[7].

There were 11 living donors (7 women and 4 men, aged 29-56 years, mean 41.5 years) and one cadaveric donor in this group. The clinical data of the donors is shown in Table 2.

| Right side graft | Left side graft | Dual-graft GRWR (%) | ||||||

| No. | Gender/age (yr) | Relation | Weight (g) | GRWR (%) | Gender/age (yr) | Relation | Weight (g) | |

| 1 | F/56 | Mother | 6301 | 0.90 | M/27 | Cadaveric | 230 | 1.22 |

| 2 | M/35 | Brother in law | 410 | 0.71 | F/52 | Brother | 193 | 1.04 |

| 3 | F/35 | Wife | 400 | 0.53 | M/55 | Uncle in law | 280 | 0.91 |

| 4 | F/29 | Wife | 470 | 0.66 | M/45 | Sister | 197 | 0.94 |

| 5 | F/39 | Wife | 6141 | 0.94 | M/42 | Brother | 225 | 1.29 |

| 6 | F/342 | Sister | 310 | 0.53 | F/31 | Sister | 300 | 1.03 |

In case 1 and case 5, whose GRWR was 0.90% and 0.94% respectively, dual-graft LDLTs were performed because macrosteatosis of their livers ranged from 20% to 25%. Cadaveric donor liver was split into two parts. The left lobe was used as one portion of dual grafts, and the right lobe including the middle hepatic vein was used in another adult liver transplantation[8].

Ultrasound examinations of the recipients were retrospectively analyzed. Ultrasound scans were performed using a HDI 5000 scanner (Philips Medical Systems, Bothell, WA) with a 2-5-MHz wide band convex transducer or a Sequoia 512 (Acuson, Mountain View, CA, USA) with a 2-6-MHz wide band convex transducer. Patients were examined by ultrasound daily until postoperative day 14 and once a week thereafter until hospital discharge. Intercostal views of the right upper quadrant of the abdomen were obtained to examine the right graft and subcostal views were used to evaluate the left graft. Gray scale and color flow images as well as Doppler spectrums were detected. Angle-corrected velocities were examined with the Doppler angle less than 60°. Parenchyma echogenicity, patency of the hepatic vessels, biliary system and the fluid collection of the thorax and abdomen were documented.

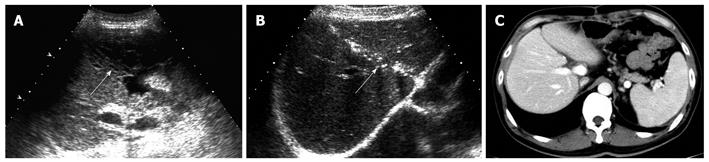

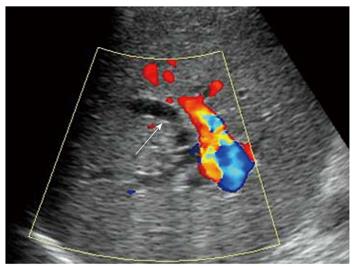

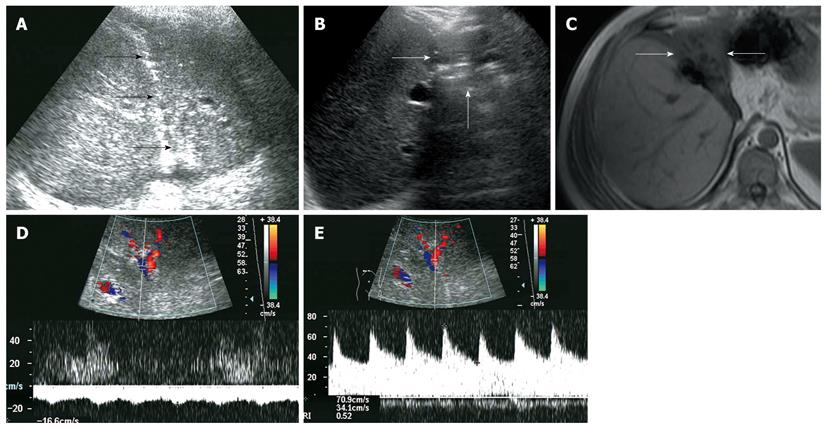

All recipients survived the dual-graft A-ALDLT surgery. All recipients (6/6) had bilateral pleural effusion and 2 patients underwent ultrasound-guided drainage. Four patients had episodes of postoperative abdominal complications, including fluid collection between the grafts in 3 patients (Figure 1), and 2 had intrahepatic biliary dilatation (Figure 2). The left-sided graft shrank in size in one patient in whom hepatofugal flow of the left portal vein was detected 1 mo after surgery (Figure 3). To-and-fro portal venous flow of the left portal vein was found in another case at a routine follow-up 2 years after surgery with a normal size of the left graft. One patient died of tumor recurrence.

All donors recovered with an uneventful process.

The significant gap between available cadaveric grafts and the number of patients on the waiting list for liver transplant triggered the rapid adoption of the right lobe liver transplantation[9-11]. Although the surgical technique of A-ALDLT achieved great progress, SFS grafts still remain a problem[12]. Dual-graft liver transplantation provides an option when the largest single graft available is still small for the recipient.

Dual-graft A-ALDLT is a complicated procedure, therefore, recipients should be monitored intensively after surgery. Ultrasonography has been regarded as the initial imaging modality of choice allowing bedside assessment for detection and follow-up of early and delayed complications, and facilitating interventional procedures[13].

Postoperative pleural effusion is common in liver transplantation recipients. Most of the cases need no special intervention with a small amount of fluid. When the amount of the fluid was large, which may result in atelectasis and higher risk of pulmonary infection and further affected the pulmonary function, ultrasound-guided drainage of the pleural effusion may help resolve the problem.

Hepatofugal portal venous flow was regarded as a serious prognostic sign of critical liver damage after liver transplantation[14,15], but the situation is different in dual-graft A-ALDLT. In our 2 cases, hepatofugal portal venous flow of the left graft was detected, while the hepatic function tests remain normal. This phenomenon could be explained by a compensatory enlargement of the right-sided graft which could meet the metabolic demand of the body even with a compromised left-sided graft. Persistent monophasic Doppler spectrum of the left hepatic vein was obtained during quiet breathing, stenosis of the left hepatic vein was suggested according to Meir and Ko’s research[16,17], which may lead to an increased sinusoidal pressure, then the portal vein served as a drainage vein and finally resulted in the atrophy of the graft.

A dual-graft A-ALDLT also has a problem of postoperative biliary complications. Ultrasound detected intrahepatic biliary dilation in 2 patients, but failed to locate the stenosis site. Compared with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiography, ultrasonography is less sensitive in detecting biliary strictures and ischemic type biliary lesions after liver transplantation[18,19], but ultrasonography is reported to have a high negative predictive value of 95% in the diagnosis of biliary tract complications[20]. Therefore, ultrasound could be used as a screening technique in the aspect of biliary complications.

Fluid collection between the grafts was common in dual-graft LDLT, which occurred in 3 recipients, because a drainage tube was not routinely placed between the grafts. Besides detection, ultrasound facilitates the fluid aspiration procedure which is important to the differential diagnosis of bile leakage or ascites and beneficial to the recovery of patients.

Indeed, some other techniques including splenic artery embolization or ligation, permanent or temporary portacaval shunts play an important role in preventing SFSS under a specific condition that GRWR ratio is near 0.8%[2]. When the graft is too small, LDLT poses a great danger for the recipients. During the follow-up of 11 donors and 6 recipients over 18 mo, SFSS was not found in the recipients. No liver failure occurred in donors and recipients. Only one patient died of tumor recurrence. Therefore, dual-graft LDLT should be regarded as a feasible method to avoid SFSS if GRWR of the recipients with portal hypertension or acute liver failure was less than 0.8%. However, the number is small and more clinical experience is required.

In conclusion, although A-ALDLT using dual grafts takes more efforts and is technically complicated, it is safely feasible and can increase the donor pool. Whenever a right lobectomy appears to be critical for the donor, the possibility of dual-graft A-ALDLT should be evaluated and discussed to minimize the combined family risk. Postoperative sonographic monitoring of the recipient is important for the early detection and intervention of vascular and non-vascular complications, which is critical to the recovery of recipients.

Dual-graft adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation (A-ALDLT) was designed to overcome the problem of small-for-size graft and reduce the overall family risk. Because of the complexity of this procedure, intensive postoperative monitoring of the recipient is required. There have been few reports about the sonographic findings of dual-graft A-ALDLT to date.

Dual-graft A-ALDLT was evaluated with ultrasonography, with special emphasis on the postoperative complications.

The authors reported six patients who received dual-graft LDLT. Normal and abnormal sonographic findings were discussed. Postoperative sonographic monitoring of the recipient is important for the early detection and intervention of vascular and non-vascular complications, which is critical to the recovery of recipients.

Ultrasound is important in the diagnosis of postoperative complications and helpful in some interventions, such as ultrasound-guided drainage of fluid. This report adds some evidences to the safety and feasibility of dual-graft liver transplantation by following up the recipients and donors.

Living donor liver transplantation: It is the replacement of a diseased liver using partial healthy liver allograft donated by members of the family.

This is a nice study, and can be published after minor revisions. Patient number for the dual-graft LDLT procedure appears small (n = 6), but is still the largest published to date. Some editing of the language is needed throughout.

Peer reviewer: Paul E Sijens, PhD, Associate Professor, Radiology, UMCG, Hanzeplein 1, 9713GZ Groningen, The Netherlands

S- Editor Wang YR L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Soejima Y, Taketomi A, Ikegami T, Yoshizumi T, Uchiyama H, Yamashita Y, Meguro M, Harada N, Shimada M, Maehara Y. Living donor liver transplantation using dual grafts from two donors: a feasible option to overcome small-for-size graft problems? Am J Transplant. 2008;8:887-892. |

| 2. | Chen Z, Yan L, Li B, Zeng Y, Wen T, Zhao J, Wang W, Xu M, Yang J. Prevent small-for-size syndrome using dual grafts in living donor liver transplantation. J Surg Res. 2009;155:261-267. |

| 3. | Hashikura Y, Ichida T, Umeshita K, Kawasaki S, Mizokami M, Mochida S, Yanaga K, Monden M, Kiyosawa K. Donor complications associated with living donor liver transplantation in Japan. Transplantation. 2009;88:110-114. |

| 4. | Brown RS Jr, Russo MW, Lai M, Shiffman ML, Richardson MC, Everhart JE, Hoofnagle JH. A survey of liver transplantation from living adult donors in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:818-825. |

| 5. | Troisi R, Ricciardi S, Smeets P, Petrovic M, Van Maele G, Colle I, Van Vlierberghe H, de Hemptinne B. Effects of hemi-portocaval shunts for inflow modulation on the outcome of small-for-size grafts in living donor liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:1397-1404. |

| 6. | Heaton N. Small-for-size liver syndrome after auxiliary and split liver transplantation: donor selection. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:S26-S28. |

| 7. | Hata S, Sugawara Y, Kishi Y, Niiya T, Kaneko J, Sano K, Imamura H, Kokudo N, Makuuchi M. Volume regeneration after right liver donation. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:65-70. |

| 8. | Chen Z, Yan L, Li B, Zeng Y, Wen T, Zhao J, Wang W, Yang J, Ma Y, Liu J. Successful adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation combined with a cadaveric split left lateral segment. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:1557-1559. |

| 9. | Broelsch CE, Frilling A, Testa G, Malago M. Living donor liver transplantation in adults. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:3-6. |

| 10. | Chen CL, Fan ST, Lee SG, Makuuchi M, Tanaka K. Living-donor liver transplantation: 12 years of experience in Asia. Transplantation. 2003;75:S6-S11. |

| 11. | Russo MW, Brown RS Jr. Adult living donor liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:458-465. |

| 12. | Sugawara Y, Makuuchi M. Small-for-size graft problems in adult-to-adult living-donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2003;75:S20-S22. |

| 13. | O’Brien J, Buckley AR, Browne R. Comprehensive ultrasound assessment of complications post-liver transplantation. Eur J Radiol. 2010;74:206-213. |

| 14. | Kita Y, Harihara Y, Sano K, Hirata M, Kubota K, Takayama T, Ohtomo K, Makuuchi M. Reversible hepatofugal portal flow after liver transplantation using a small-for-size graft from a living donor. Transpl Int. 2001;14:217-222. |

| 15. | Kaneko T, Sugimoto H, Inoue S, Tezel E, Ando H, Nakao A. Doppler ultrasonography for postoperative hepatofugal portal blood flow of the intrahepatic portal vein. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1825-1829. |

| 16. | Ko EY, Kim TK, Kim PN, Kim AY, Ha HK, Lee MG. Hepatic vein stenosis after living donor liver transplantation: evaluation with Doppler US. Radiology. 2003;229:806-810. |

| 17. | Scheinfeld MH, Bilali A, Koenigsberg M. Understanding the spectral Doppler waveform of the hepatic veins in health and disease. Radiographics. 2009;29:2081-2098. |

| 18. | Zoepf T, Maldonado-Lopez EJ, Hilgard P, Dechêne A, Malago M, Broelsch CE, Schlaak J, Gerken G. Diagnosis of biliary strictures after liver transplantation: which is the best tool? World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2945-2948. |

| 19. | Buis CI, Hoekstra H, Verdonk RC, Porte RJ. Causes and consequences of ischemic-type biliary lesions after liver transplantation. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13:517-524. |