Published online Aug 14, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i30.3834

Revised: May 13, 2010

Accepted: May 20, 2010

Published online: August 14, 2010

AIM: To investigate the significance of ileocolonoscopy with histology in the evaluation of post-transplantation persistent diarrhea (PD).

METHODS: We retrospectively reviewed all records of renal transplant patients with PD, over a 3-year period. All patients were referred for ileocolonoscopy with biopsy, following a negative initial diagnostic work up. Clinical and epidemiological data were compared between cases with infectious or drug-induced diarrhea.

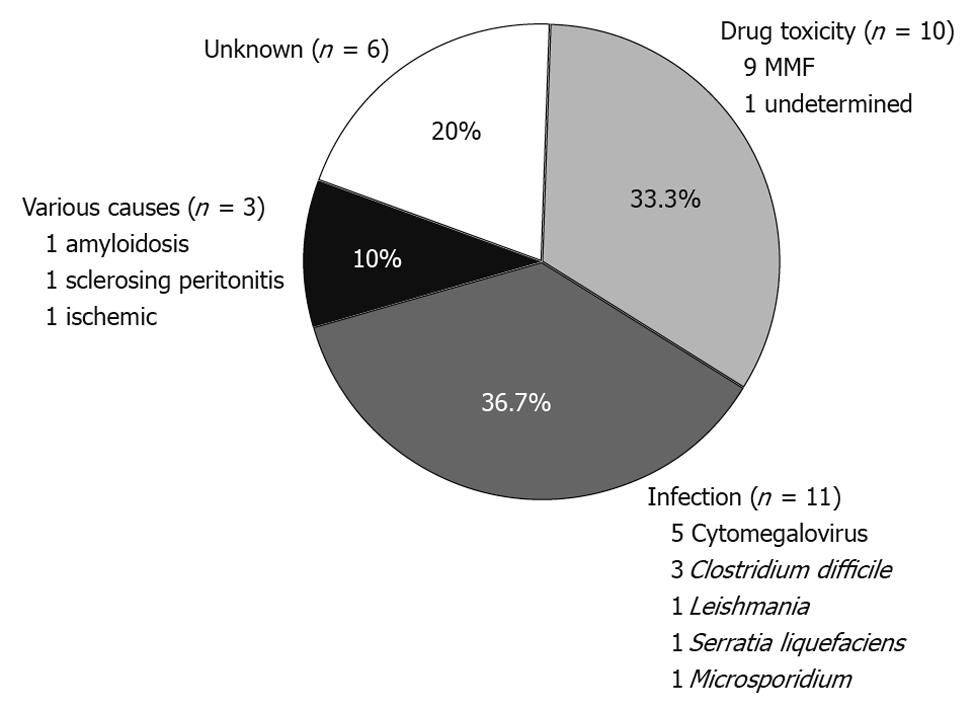

RESULTS: We identified 30 episodes of PD in 23 renal transplant patients (1-3 cases per patient). There were 16 male patients and the mean age at the time of PD was 51.4 years. The average time from transplantation to a PD episode was 62.3 ± 53.2 mo (range 1-199 mo). Ileocolonoscopy detected mucosal abnormalities in 19 cases, whereas the intestinal mucosa appeared normal in 11 cases. Histological examination achieved a specific diagnosis in 19/30 cases (63.3%). In nine out of 11 cases (82%) with normal endoscopic appearance of the mucosa, histological examination of blinded biopsies provided a specific diagnosis. The etiology of PD was infectious in 11 cases (36.6%), drug-related in 10 (33.3%), of other causes in three (10%), and of unknown origin in six cases (20%). Infectious diarrhea occurred in significantly longer intervals from transplantation compared to drug-related PD (85.5 ± 47.6 mo vs 40.5 ± 44.8 mo, P < 0.05). Accordingly, PD due to drug-toxicity was rarely seen after the first year post-transplantation. Clinical improvement followed therapeutic intervention in 90% of cases. Modification of immunosuppressive regimen was avoided in 57% of patients.

CONCLUSION: Early ileocolonoscopy with biopsies from both affected and normal mucosa is an important adjunctive tool for the etiological diagnosis of PD in renal transplant patients.

- Citation: Bamias G, Boletis J, Argyropoulos T, Skalioti C, Siakavellas SI, Delladetsima I, Zouboulis-Vafiadis I, Daikos GL, Ladas SD. Early ileocolonoscopy with biopsy for the evaluation of persistent post-transplantation diarrhea. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(30): 3834-3840

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i30/3834.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i30.3834

Diarrhea occurs frequently following renal transplantation, with reported incidences as high as 64% in large clinical trials[1-3]. Although several cases are benign and easily manageable, post-transplantation diarrhea can persist for a long period and compromise the health status of the patients. In particular, it leads to water and electrolyte disturbances, interferes with the absorption of immunosuppressive drugs, often requires hospital admission, and thus negatively affects the quality of life of the patients[4]. An association between post-transplantation diarrhea and decreased graft and patient survival has also been reported[5].

The diagnostic algorithm of post-transplantation diarrhea should take into consideration the specific characteristics of this population, particularly the presence of significant immunosuppression[6,7]. Infectious agents are often implicated; however, manifestation of enteric infections can vary considerably in this population[8,9]. Atypical presentations and severe forms of common infections frequently occur, whereas opportunistic infections with unusual microorganisms are also encountered. On the other hand, immunosuppressive regimens can cause intense and persistent diarrhea (PD)[10]. The most prominent example is toxicity of mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), which can cause enterocolitis in a substantial proportion of patients[11-14], requiring modification of the immunosuppressive regimen. However, reducing the dose of immunosuppression might lead to graft loss[15].

In the present study we have analyzed all cases of PD in renal transplant patients in our Hospital between July 2006 and June 2009. Our aim was to investigate the utility of early ileocolonoscopy, with biopsies taken both from identified lesions and blindly from normal looking mucosa, in establishing a definitive diagnosis for the diarrheal episode.

We retrospectively reviewed the records of all renal transplant patients who presented with PD and had ileocolonoscopy as part of their diagnostic work-up in our hospital between July 2006 and June 2009.

All patients were followed at the Renal Transplantation Unit of our Hospital. Demographic, epidemiological, and clinical characteristics of the patients at the time of each diarrheal episode were retrieved from the medical files. We defined PD as an episode of diarrhea with the following characteristics: (1) change in the bowel habits with more than three movements per day and decreased stool consistency lasting longer than 2 wk; (2) an etiological diagnosis was not established after initial testing, including detailed history and clinical examination, extensive hematological, and biochemical tests, as well as stool cultures for enteric pathogens, examination for ova and parasites, and examination for Clostridium difficile toxins-A and B; (3) failure of diarrhea to resolve following simple dietetic modifications and non-immunosuppressive medication adjustment; and (4) further testing including ileocolonoscopy was considered necessary by the attending nephrologist, because diarrhea interfered with health status and quality of life of the patient. All patients with PD were tested with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for cytomegalovirus (CMV) in blood; however, colonoscopy was always performed to detect endoscopic and/or histologically evident CMV-colitis.

Over the 3-year study period there was an agreed standard practice between the Renal Transplantation Unit and G.I. Endoscopy Unit of the 1st Department of Internal Medicine, to which renal transplant patients with PD are referred for ileocolonoscopy. Polyethylene glycol was used for bowel preparation. Sodium phosphate-based regimens were avoided due to their reported nephrotoxicity. Colonoscopy was performed with sedation (midazolam) and analgesia (pethidine), as required. During endoscopy, multiple biopsies were taken from all areas with mucosal abnormalities as well as blind biopsies from normal looking mucosa of the terminal ileum and throughout the colon (4-6 biopsies from right and left colon, respectively). Upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract endoscopy was performed selectively according to the clinical judgment of the treating physicians.

We defined the following categories of PD in relation with the underlying cause: (1) infectious, when a microorganism with an established role as a diarrhea-causing agent was detected by microbiological, histological, or molecular methods; (2) drug-induced, when infectious agents were excluded and histological findings consistent with pharmaceutical injury (most often MMF-related) were detected in the biopsy specimens. Histological findings highly suggestive of MMF-colitis, included: (a) mucosal abnormalities characterized by atrophy, crypt architectural distortion, flattened crypt epithelium, increased cell apoptosis and regenerative epithelial changes; and (b) edema, moderate inflammatory infiltrations with increased number of eosinophils, crypt abscesses and cryptitis, and, in the more severe cases, focal erosions or ulceration[13]. In addition, a clear beneficial effect of modification of the immunosuppressive regimen (MMF-dose reduction or switching to Myfortic or azathioprine) on the severity of PD was required to confirm a drug (MMF)-associated etiology of diarrhea; (3) Other, when a definitive cause (not associated with immunosuppressive medications or infectious agents) was established by clinical, laboratory, and histological findings; and (4) unknown, when no causative factor was identified. This group included cases with non-specific changes either in endoscopy and/or at histology.

The SPSS software was used for the analysis. Continuous variables were analyzed by the independent t-test or Mann-Whitney test (if they did not meet the criteria for parametric comparison). Categorical variables were studied by corrected χ2 test. For all comparisons a probability level (P) of 0.05 was considered significant.

Over the study period, 30 ileocolonoscopies were performed for 30 separate episodes of PD in 23 renal transplant patients (Table 1). One patient had three episodes, five had two, and seventeen patients had one episode of PD. In all but one patient, the cause of PD differed between separate episodes. There was a clear predominance of males (2.3:1 male/female ratio), independently of the etiology of diarrhea (Table 1). The cause of renal failure and transplantation was polycystic kidney disease in four patients, kidney stone disease in three, whereas Henoch-Schönlein purpura, IgA nephropathy, recurrent kidney infections, renal hypoplasia, medullary cystic disease, and polyarteritis nodosa accounted for one case each. The etiology was unknown in 10 patients.

| Total | Drug | Infection | Non-drug, non-infectious2 | P3 | |

| No. of cases of persistent diarrhea | 30 | 10 | 11 | 9 | |

| Gender, n (%) | |||||

| Female | 8 (26.7) | 3 (30) | 2 (18.2) | 3 (33.3) | |

| Male | 22 (73.3) | 7 (70) | 9 (81.8) | 6 (66.7) | |

| Donor type | |||||

| Cadaveric | 43.3 | 60 | 27.3 | 44.4 | |

| Living | 56.7 | 40 | 72.7 | 55.6 | NS |

| Age at diarrheal episode (yr), mean ± SD (range) | 51.4 ± 15.5 (24-76) | 46.9 ± 17.1 (27-76) | 52.6 ± 10 (40-70) | 54.8 ± 19.4 (24-75) | NS |

| History of previous diarrheal episode, n (%) | 21 (70) | 4 (40) | 9 (81.8) | 8 (89) | 0.081 |

| Time since transplantation (mo), mean ± SD (range) | 62.3 ± 53.2 (1-199) | 40.5 ± 44.8 (1-142) | 85.5 ± 47.6 (2-179) | 58.1 ± 61.8 (6-199) | 0.038 |

| Immunosuppressive regimen4, n (%) | |||||

| Mycophenolate mofetil + tacrolimus | 18 (60) | 6 (60) | 6 (54.5) | ||

| Mycophenolate mofetil + cyclosporine | 2 (6.6) | 1 (9.1) | |||

| Mycophenolate mofetil + sirolimus | 2 (6.6) | 1 (10) | 1 (9.1) | ||

| Mycophenolate mofetil + everolimus | 1 (3.3) | 1 (10) | |||

| Everolimus + tacrolimus | 2 (6.6) | 2 (18.2) | |||

| Tacrolimus | 2 (6.6) | ||||

| Mycophenolate sodium + tacrolimus | 3 (10) | 2 (20) | 1 (9.1) | ||

| Hospital stay (d), mean ± SD (range) | 18.1 ± 30.6 (0-169) | 8.5 ± 8.5 (0-22) | 17.4 ± 11.6 (0-37) | 29.4 ± 53.8 (0-169) | 0.076 |

| Outcome, n (%) | |||||

| Cessation of diarrhea | 22 (73.3) | 9 (90) | 9 (82) | 4 (44.4) | NS |

| Improvement | 5 (16.7) | 5 (55.6) | |||

| Death/graft loss | 3 (10) | 1 (10) | 2 (18) |

The immunosuppressive regimens that were administered at the time of each case of PD are shown in Table 1. All patients with more than one episode of PD were receiving the same immunosuppressive medications in all episodes, with the exception of one patient who was switched from MMF/tacrolimus (1st episode) to everolimus/tacrolimus (2nd and 3rd episodes) and a second patient in whom MMF/tacrolimus was changed to mycophenolate sodium/tacrolimus.

Twenty endoscopies were performed in inpatients and ten in outpatients. The cecum was reached in 26/30 colonoscopies (86.7%), with terminal ileum intubation in the vast majority of cases (22/26 with cecum intubation, 85%). We did not observe any serious complications related either to the preparation for colonoscopy, the use of sedatives/analgesics, or the procedure itself.

The diagnostic yield of ileocolonoscopy and histological examination of endoscopically obtained intestinal specimens are shown in Table 2. Biopsies were taken in all but one patient, in whom diagnosis of pseudomembranous colitis was established by typical history of prior antibiotic administration and endoscopic findings. Ileocolonoscopy revealed mucosal abnormalities in 2/3 of the patients. The most frequently encountered findings were edema (loss of submucosal vascular pattern) and erythema of the mucosa, which were observed in 11 cases. More severe lesions included colonic ulceration (three cases), stenosis (two cases), submucosal hemorrhage (one case), and formation of pseudomembranes (two cases). We did not observe any endoscopic findings that were exclusively associated with infectious or drug-induced diarrhea (with the exception of pseudomembranous colitis).

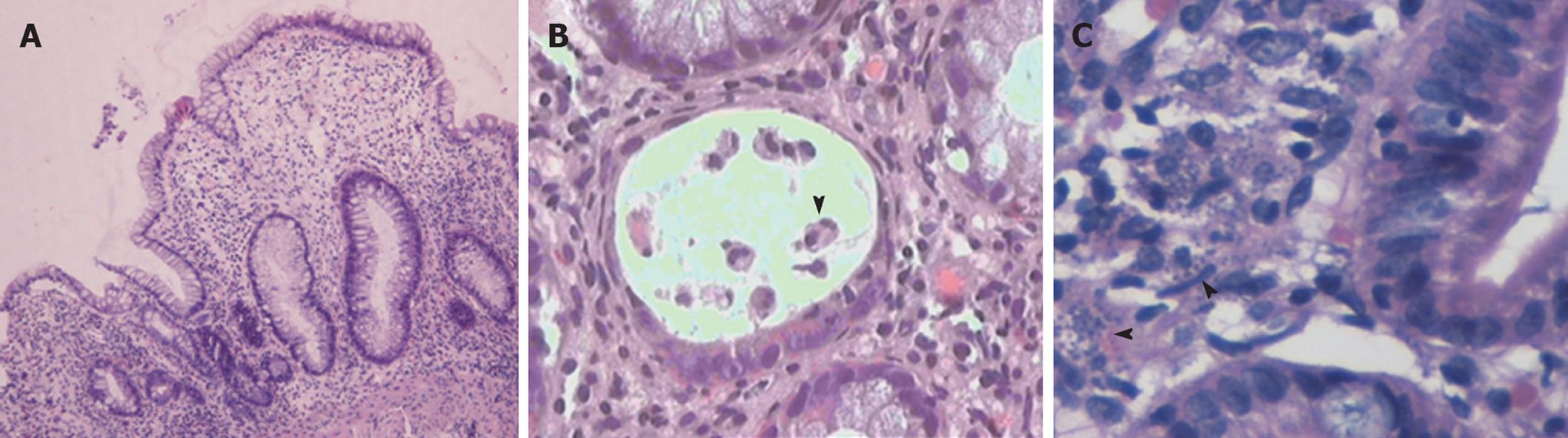

Histological examination of biopsies obtained during endoscopy provided a definitive diagnosis in 19/30 cases (63.3%). More importantly, histology allowed for a specific diagnosis in nine out of 11 cases with normal endoscopic examinations (Table 2). Overall, an infectious cause was identified in 11 cases (Figure 1). The most prevalent infection was due to CMV, accounting for 16.6% of all cases. Interestingly, in 3/11 infectious cases (27%) there were no mucosal abnormalities seen on endoscopy. In three cases, diagnosis was established histologically in biopsy specimens taken from areas of normal looking mucosa (Table 2). These included two cases of CMV infection and one case infected with microsporidium. A case of leishmaniasis was diagnosed histologically by the recognition of the dot-like organisms within mucosal macrophages (Figure 2C). These were also revealed by Giemsa stain while PAS stain was negative.

In our study, we identified 10 episodes of PD (33.3%) that were related to toxicity of immunosuppressive drugs (Figure 1). All patients with drug-related diarrhea were receiving mycophenolate (eight MMF and two mycophenolate sodium) in combination with tacrolimus (eight cases), everolimus (one case), or sirolimus (one case). In the majority of drug-induced PD (6/10, 60%) the colonic mucosa looked normal on colonoscopy. Nevertheless, histological evaluation of blindly collected biopsies revealed mucosal changes consistent with MMF-colitis in all cases; thus establishing the diagnosis of drug-induced injury. These findings included mucosal abnormalities such as edema, atrophy, crypt architectural distortion, regenerative epithelial changes, and increased cell apoptosis with intraluminal apoptotic bodies (Figure 2A and B).

In our study there were three cases where a definitive diagnosis unrelated to infection or drug-toxicity was established. In the first patient, intestinal amyloidosis was diagnosed by histological examination and appropriate staining of a biopsy specimen obtained from the rectum. The second case involved a patient with sclerosing peritonitis. The pathophysiology of diarrhea was associated with external compression of the intestine by the sclerotic tissue and the accompanying motility and structural abnormalities, as diarrhea was completely abrogated following effective surgical decompression. Finally, in the third case, diarrhea was considered of ischemic origin as no other etiology was found and histology was compatible with ischemic intestinal injury. Taken together, these results show that endoscopy with histological examination of both affected and normal mucosa achieves a definitive diagnosis in the vast majority of PD in renal transplant patients.

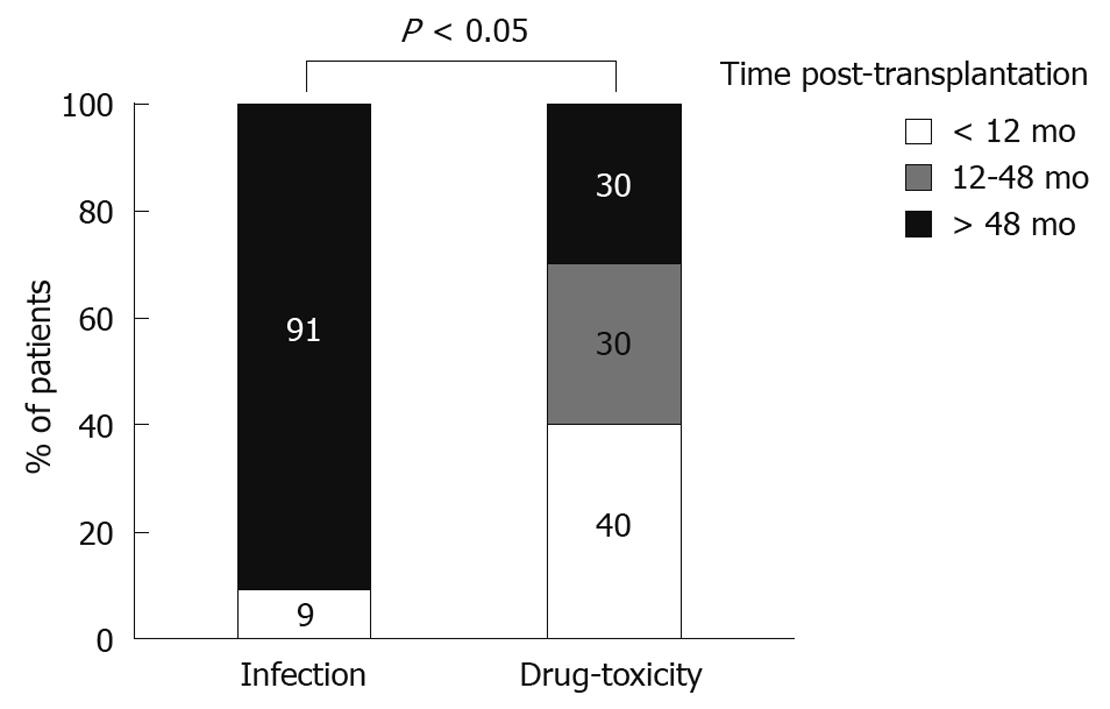

As our initial analysis showed that the majority of cases with PD were of infectious or pharmaceutical etiology, we then compared these two distinct groups for several characteristics. We observed no association between the type of diarrhea and the gender or age of the patient, or the type of donor (cadaveric vs living) (Table 1). In contrast, the time from transplantation to the PD episode differed significantly according to the etiological factor. In particular, this interval was considerably shorter in drug-related (40.5 ± 44.8 mo), as compared to infectious diarrhea (85.5 ± 47.6 mo, P < 0.05). There was a statistically significant difference between infectious and drug-induced PD (P < 0.05) in regards to their temporal distribution (Figure 3). In particular, while all but one case of infectious PD (91%) occurred later than 4 years post-transplantation, drug toxicity was usually seen at earlier time points. Accordingly, infection accounted for 14% of early episodes, whereas pharmaceutical toxicity accounted for 57%. In contrast, late episodes were caused primarily by infections (56%) and rarely by drugs (16.6%). In all, these results indicate that the time post-transplantation should be taken into consideration when searching for the etiology of PD in renal transplant patients, as different causes underlie early vs late episodes.

All but one case of infectious diarrhea required admission to the hospital, (91% admission rate) (Table 1). In contrast, fewer patients with drug-induced PD were admitted (60% admission rate). There was a trend towards longer hospital stay for patients with infectious diarrhea (mean hospital stay: 17.4 ± 11.6 d vs 8.5 ± 8.5 d for the drug-induced group, P = 0.076) (Table 1).

The overall outcome of PD was good, with cessation or improvement of diarrhea in 90% of cases (Table 1). There were two deaths in the infectious group, both unrelated to diarrhea. One patient with pseudomembranous colitis had a complicated clinical course due to disseminated fungal infection and was transferred to ICU where he eventually died. The other patient suffered from visceral leishmaniasis that had a fatal outcome.

Modification of immunosuppressive regimen was introduced in 12 cases. In five there was a switch from MMF to enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium, whereas in two the dose of mycophenolate was decreased with favorable outcomes in all cases. In four occasions mycophenolate had to be replaced by azathioprine. Finally, in one patient with drug-induced PD, diarrhea proved to be self-limited and required no change of immunosuppression. In our study, there was one case of graft loss in a patient with severe immunosuppression-related complications who had to stop all drugs with eventual loss of the graft.

In the present study we demonstrated that early ileocolonoscopy combined with histology of bowel mucosa, even without macroscopic abnormalities, is a critical component of the diagnostic evaluation of PD in renal transplant patients. We have shown that this approach provides a definitive diagnosis in the majority of cases, allowing prompt and specific treatment of the underlying cause, avoiding unnecessary modifications of the immunosuppressive regimen, and leading to favorable patient and graft outcome. Our data also indicate that PD is more likely due to drug-associated toxicity during the first post-transplantation year, while infectious diarrhea may occur throughout the post-transplantation period and is usually the cause of diarrhea after 4-year post-transplantation.

The majority of published studies on post-transplantation diarrhea did not take into account the severity or the duration of the episode[1-3,5]. In our study we focused on diarrhea that was judged as persistent, both in terms of long duration as well as of interference with the wellbeing of patients. We believe that these are the most clinically relevant cases and require extensive evaluation for the underlying causative agent. Our findings clearly show that there should be a low threshold for early ileocolonoscopy with histological examination in these patients. Such an approach is supported by the high percentage (80%) of definitive diagnoses that was accomplished in our study.

In a recent publication, a diagnostic algorithm for post-transplantation diarrhea was proposed, which introduced colonoscopy late in the course of evaluation and, more significantly, after modifications in immunosuppressive drugs were applied[16]. In fact, reduction of MMF is among the first measures taken in patients with post-transplant diarrhea[17]. This leads to cessation of diarrhea in a considerable proportion of cases, therefore avoiding the need for invasive tests such as colonoscopy. On the other hand, reducing the dose of immunosuppression often results in graft dysfunction[15,18,19]. In fact, in our study, the single episode of graft loss was associated with immunosuppression cessation due to severe toxicity, including drug-induced-diarrhea. Our results support the use of early endoscopy with histology in prolonged or refractory cases of diarrhea, as we were able to document non-drug-related causes in 46% of cases, thus avoiding unnecessary modifications of immunosuppressive regimens.

Early colonoscopy was suggested in a recent study on post-transplantation diarrhea, when there is strong clinical suspicion for CMV-colitis[20], including cases with positive PCR for CMV in the blood. Our findings support the use of colonoscopy with histology in this population, as it helps in establishing the localization of CMV in the intestine and provides causality for chronic diarrhea. In fact, in our series, one of five cases with CMV-colitis had negative CMV-PCR in the blood, and a second one had very low number of CMV-DNA copies. Moreover, in some cases with positive CMV-PCR in the blood, colonoscopy and histology indicated absence of CMV-colitis, despite the presence of diarrhea, which was attributed to other causes.

To our knowledge there is only one published study that reported on the role of colonoscopy in renal transplant patients with diarrhea. Contrary to our study, Korkmaz et al[21] showed a 55% failure to establish a diagnosis with colonoscopy and/or histology. The higher rates observed in our study might be attributed to several factors. First, the severity of diarrhea in the Korkmaz study is not reported; it might, therefore, be the case that some colonoscopies were performed in milder cases with no obvious causative agent. Second, the accumulated experience on the histological lesions of MMF-colitis allowed us to use better-defined criteria for drug-induced toxicity; it is possible that such cases are included in the large number of non-specific colitis cases in the study by Korkmaz et al[21]. Finally, we took blinded biopsies in every patient, which was not the case in the aforementioned study. In another recent study only apparent lesions were biopsied during colonoscopy[22]. Our data clearly showed that histology of normal-appearing mucosa revealed pathognomonic findings in a considerable percentage of renal transplant patients with PD. In our study, this approach yielded a diagnosis in 27% of infection-related and in 60% of drug-induced cases of diarrhea.

Infectious agents and drugs accounted for the majority of PD cases in our cohort. This is in line with previous studies[23,24]. We detected a significant difference between the two groups (infectious vs drug-induced) regarding the time they occurred post-transplantation. In particular, the majority of drug-induced cases took place in the first years following transplantation. This distinction has also been observed in other studies[16]. This may be explained by the fact that intolerance to immunosuppressive regimen is expected to occur within relatively short time after their initiation[25]. In contrast, in our study, intestinal infection was diagnosed later than 4 years post-transplantation, almost exclusively. A temporal distribution of various infections post-transplantation has been reported[26]. These data, as well as our present findings, indicate that the search for PD etiology should be tailored to the individual patient, taking into consideration the time post-transplantation. In the case of an episode that takes place long after transplantation, intensive search for infectious agents is primarily required.

We were not able to establish a diagnosis in 6/30 cases (20%), including four that were classified as non-specific colitis. Follow-up revealed that diarrhea ceased or was greatly improved, indicating that self-limited infections and/or unspecified pharmacotoxicity underlay these cases. In fact, in one case Candida albicans was isolated from the stools, whereas in two others CMV-viremia was detected. However, since a direct proof of causality was not established, we classified these cases as non-specific colitis and not infectious. Only in two cases of unknown etiology was modification of immunosuppressive regimen considered necessary.

In conclusion, our results indicate that ileocolonoscopy has an important impact in the management of renal transplant patients with PD and should be an adjunctive tool for the causative diagnosis of PD. Endoscopy should be considered only after initial measures have failed to induce clinical improvement. These measures may include adjustment of the immunosuppressive regimen, particularly when diarrhea manifests during the initial post-transplantation months as the prevalence of drug-related causes is increased during that period. In any case, biopsies should always be taken from the lower GI tract as histology achieves a definitive diagnosis in the majority of cases, even when the intestinal mucosa appears macroscopically normal. This approach may offer the opportunity for specific treatment and lead to improved outcomes following renal transplantation.

Diarrhea is among the most common complications in patients who receive renal transplants and has been associated with poor outcomes in terms of quality of life as well as graft and patient survival. Infectious agents often cause diarrhea due to the universal administration of immunosuppressive regimens in this population. Immunosuppressants can themselves cause significant gastrointestinal toxicity, the most prominent example being mycophenolate mofetil-enterocolitis.

Previous studies have reported diagnostic algorithms for the evaluation of post-transplantation diarrhea. Endoscopic and histological studies of the lower gastrointestinal tract have been incorporated only at the late steps of diagnostic protocols, usually when extensive clinical and laboratory work-up has been negative and modifications in the immunosuppressive scheme have been ineffective to induce diarrhea cessation.

In the present study, the authors investigated the usefulness of a standard approach for the evaluation of persistent diarrhea (PD) in renal transplant patients, which utilized an early ileocolonoscopy, i.e. as soon as limited laboratory testing came back negative. Moreover, biopsies were routinely taken both from all identified lesions but also blindly from normal looking mucosa. The present study demonstrated a high efficacy of this diagnostic scheme in establishing a definitive diagnosis for the diarrheal episode.

The application of early ileocolonoscopy with standard tissue sampling may facilitate etiologic diagnosis and targeted treatment of PD in renal transplant patients; thus avoiding unnecessary changes in the immunosuppressive regimen. This approach may be of particular importance in the late post-transplantation period, when non-drug related causes of diarrhea are increased.

PD: an episode of diarrhea lasting longer than 2 wk and interfering with the health status and quality of life of the renal transplant patient, for which an etiological diagnosis is not established after initial clinical examination, baseline hematological and biochemical tests, as well as stool tests for infectious causes and which did not respond to simple dietetic modifications and non-immunosuppressive medication adjustments.

The authors investigated the role of colonoscopy on persistent post-transplantation diarrhea. The results indicated that colonoscopy is a valuable diagnostic tool for evaluating transplant recipients with PD. The paper is well written and data clearly presented. The work contributes to the understanding and guides management of this important complication despite the small number of patients and selection bias.

Peer reviewer: Myung-Gyu Choi, MD, Professor of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea, 505, Banpo-Dong, Seocho-Gu, Seoul 137-040, South Korea

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Stewart GJ E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Gil-Vernet S, Amado A, Ortega F, Alarcón A, Bernal G, Capdevila L, Crespo JF, Cruzado JM, De Bonis E, Esforzado N. Gastrointestinal complications in renal transplant recipients: MITOS study. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:2190-2193. |

| 2. | Altiparmak MR, Trablus S, Pamuk ON, Apaydin S, Sariyar M, Oztürk R, Ataman R, Serdengeçti K, Erek E. Diarrhoea following renal transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2002;16:212-216. |

| 3. | Gaston RS, Kaplan B, Shah T, Cibrik D, Shaw LM, Angelis M, Mulgaonkar S, Meier-Kriesche HU, Patel D, Bloom RD. Fixed- or controlled-dose mycophenolate mofetil with standard- or reduced-dose calcineurin inhibitors: the Opticept trial. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1607-1619. |

| 4. | Ekberg H, Kyllönen L, Madsen S, Grave G, Solbu D, Holdaas H. Increased prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms associated with impaired quality of life in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2007;83:282-289. |

| 5. | Bunnapradist S, Neri L, Wong W, Lentine KL, Burroughs TE, Pinsky BW, Takemoto SK, Schnitzler MA. Incidence and risk factors for diarrhea following kidney transplantation and association with graft loss and mortality. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51:478-486. |

| 6. | Ponticelli C, Passerini P. Gastrointestinal complications in renal transplant recipients. Transpl Int. 2005;18:643-650. |

| 7. | Helderman JH, Goral S. Gastrointestinal complications of transplant immunosuppression. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:277-287. |

| 8. | Subramanian AK, Sears CL. Infectious diarrhea in transplant recipients: current challenges and future directions. Transpl Infect Dis. 2007;9:263-264. |

| 9. | Pourmand G, Salem S, Mehrsai A, Taherimahmoudi M, Ebrahimi R, Pourmand MR. Infectious complications after kidney transplantation: a single-center experience. Transpl Infect Dis. 2007;9:302-309. |

| 10. | Miller J, Mendez R, Pirsch JD, Jensik SC. Safety and efficacy of tacrolimus in combination with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) in cadaveric renal transplant recipients. FK506/MMF Dose-Ranging Kidney Transplant Study Group. Transplantation. 2000;69:875-880. |

| 11. | Arns W. Noninfectious gastrointestinal (GI) complications of mycophenolic acid therapy: a consequence of local GI toxicity? Transplant Proc. 2007;39:88-93. |

| 12. | Dalle IJ, Maes BD, Geboes KP, Lemahieu W, Geboes K. Crohn's-like changes in the colon due to mycophenolate? Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:27-34. |

| 13. | Papadimitriou JC, Cangro CB, Lustberg A, Khaled A, Nogueira J, Wiland A, Ramos E, Klassen DK, Drachenberg CB. Histologic features of mycophenolate mofetil-related colitis: a graft-versus-host disease-like pattern. Int J Surg Pathol. 2003;11:295-302. |

| 14. | Kamar N, Faure P, Dupuis E, Cointault O, Joseph-Hein K, Durand D, Moreau J, Rostaing L. Villous atrophy induced by mycophenolate mofetil in renal-transplant patients. Transpl Int. 2004;17:463-467. |

| 15. | Bunnapradist S, Lentine KL, Burroughs TE, Pinsky BW, Hardinger KL, Brennan DC, Schnitzler MA. Mycophenolate mofetil dose reductions and discontinuations after gastrointestinal complications are associated with renal transplant graft failure. Transplantation. 2006;82:102-107. |

| 16. | Maes B, Hadaya K, de Moor B, Cambier P, Peeters P, de Meester J, Donck J, Sennesael J, Squifflet JP. Severe diarrhea in renal transplant patients: results of the DIDACT study. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:1466-1472. |

| 17. | Pelletier RP, Akin B, Henry ML, Bumgardner GL, Elkhammas EA, Rajab A, Ferguson RM. The impact of mycophenolate mofetil dosing patterns on clinical outcome after renal transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2003;17:200-205. |

| 18. | Knoll GA, MacDonald I, Khan A, Van Walraven C. Mycophenolate mofetil dose reduction and the risk of acute rejection after renal transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2381-2386. |

| 19. | Pascual J, Ocaña J, Marcén R, Fernández A, Galeano C, Alarcón MC, Burgos FJ, Villafruela JJ, Ortuño J. Mycophenolate mofetil tolerability and dose changes in tacrolimus-treated renal allograft recipients. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:2398-2399. |

| 20. | Korkmaz M, Kunefeci G, Selcuk H, Unal H, Gur G, Yilmaz U, Arslan H, Demirhan B, Boyacioglu S, Haberal M. The role of early colonoscopy in CMV colitis of transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:3059-3060. |

| 21. | Korkmaz M, Gür G, Yilmaz U, Karakayali H, Boyacioğlu S, Haberal M. Colonoscopy is a useful diagnostic tool for transplant recipients with lower abdominal symptoms. Transplant Proc. 2004;36:190-192. |

| 22. | Baysal C, Gür G, Gürsoy M, Ustündağ Y, Demirhan B, Boyacioğlu S, Bilgin N. Colonoscopy findings in renal transplant patients with abdominal symptoms. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:754-755. |

| 23. | Rubin RH. Gastrointestinal infectious disease complications following transplantation and their differentiation from immunosuppressant-induced gastrointestinal toxicities. Clin Transplant. 2001;15 Suppl 4:11-22. |

| 24. | Hardinger KL, Brennan DC, Lowell J, Schnitzler MA. Long-term outcome of gastrointestinal complications in renal transplant patients treated with mycophenolate mofetil. Transpl Int. 2004;17:609-616. |

| 25. | Davies NM, Grinyó J, Heading R, Maes B, Meier-Kriesche HU, Oellerich M. Gastrointestinal side effects of mycophenolic acid in renal transplant patients: a reappraisal. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:2440-2448. |

| 26. | Fishman JA, Rubin RH. Infection in organ-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1741-1751. |