INTRODUCTION

Living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) is accepted around the world with the shortage of suitable deceased donors[1-4]. The safety of the living donor, an otherwise healthy individual, is important in the ethical considerations of performing LDLT[5]. Morbidity in living donors is not rare[3,6,7]. Preoperative imaging studies are needed not only to evaluate the donor’s condition but also to exclude unsuitable candidates. The liver volume, condition of the liver parenchyma, and vascular anatomy are relatively easy to assess through imaging studies especially using multi-detector row computed tomography (MDCT). Variations in biliary anatomy are common, and in order to avoid intraoperative biliary injury, precise preoperative imaging studies are needed. However, it is difficult to evaluate biliary anatomy because of the complicated nature of various imaging modalities. There is no consensus for preoperative imaging to evaluate the donor’s biliary anatomy. Even today intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) has a very important role in the assessment of a donor’s biliary anatomy.

We identified a rare biliary anatomic variant during LDLT. The donor had the right anterior segmental duct (RASD) emptying directly into the cystic duct. In this report, we present this rare but important anatomic variant and discuss preoperative biliary imaging and the procedure for IOC.

CASE REPORT

A 35-year-old mother was scheduled to be the living donor for liver transplantation to her second son, who suffered from biliary atresia complicated with biliary cirrhosis at the age of 2 years. There were no remarkable findings in her family or past medical history. On physical examination, she had a healed operative scar in the lower abdomen as a result of two caesarean section procedures. A preoperative medical evaluation was performed and her liver volume, condition of the liver parenchyma, and hepatic vascular anatomy made her a suitable living donor. Congenital absence of the right kidney and slight prolongation of the activated partial thromboplastin time were found, which were not considered as contraindications for donor surgery. At that time, preoperative imaging of the biliary system was not performed routinely in our institution. LDLT was then performed, using an upper midline incision to recover the left lateral segment. After intraoperative ultrasound examination, cholecystectomy was performed. Before the gallbladder was removed, IOC was attempted through the incision in the cystic duct based on the conventional practice. However, the catheter would not pass easily into the cystic duct. Instead, it passed through a small hole in the side wall of the cystic duct. Using cholangiography, we found that the RASD emptied directly into the cystic duct with the catheter inserted into the RASD (Figure 1A), and the right posterior segmental duct joined the left hepatic duct. The incision in the cystic duct was repaired carefully to prevent stenosis. After removing the left lateral segment, another intraoperative cholangiogram was performed through the stump of the left hepatic duct and no stenosis at the confluence of the RASD and cystic duct was seen (Figure 1B). Her postoperative course was uneventful.

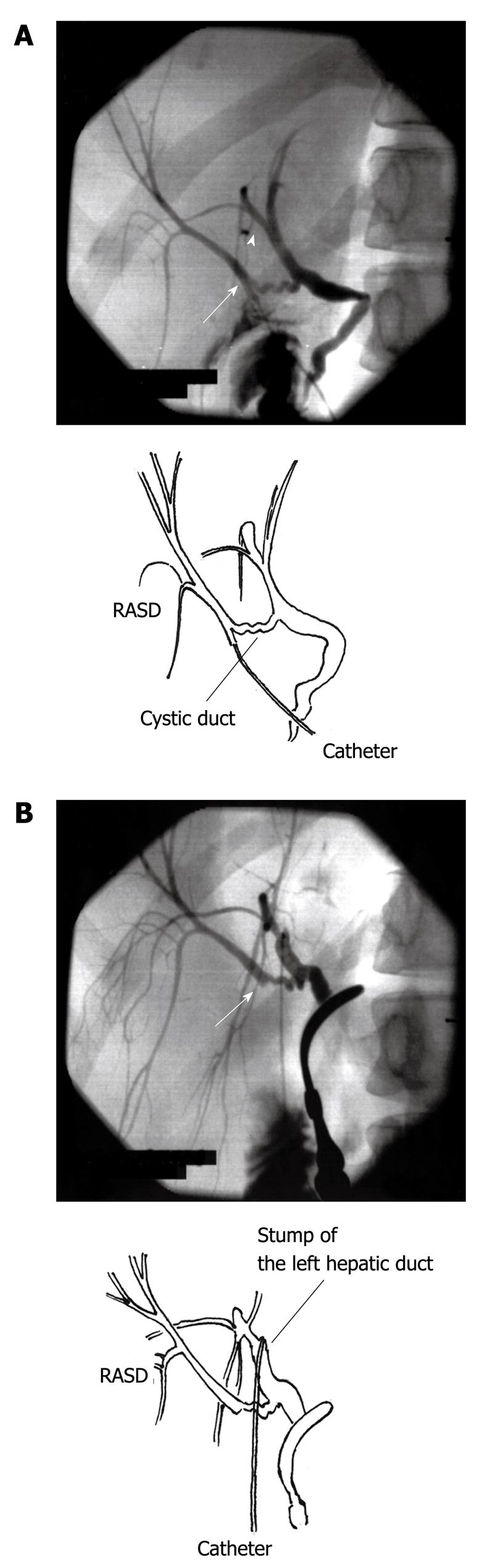

Figure 1 Intraoperative cholangiography.

A: The right anterior segmental duct (RASD) emptying into the cystic duct is seen (arrow). The catheter is in the RASD. The right posterior segmental duct joining the left hepatic duct is also shown (arrowhead); B: After the left lateral segment was recovered, no stenosis was seen at the site of the repaired cystic duct (arrow). Cholangiography was performed through the stump of the left hepatic duct.

DISCUSSION

Biliary anatomical variants are frequently encountered[8], however, the variation reported in this case is very rare[9-12]. Champetier et al[13] stated that “The cystohepatic ducts drain the entirety of a hepatic territory of variable extent into the cystic duct or gallbladder”, and they also emphasized the danger of these variants when performing a cholecystectomy.

The possibility of very rare biliary variations and the risks for the donor must be discussed in detail when obtaining informed consent. The living donor will be at risk, but continued efforts must be made to reduce the donor’s morbidity as much as possible. In this case, we encountered a rare variant of biliary duct anatomy, but avoided injury to the RASD.

One of the ethical obligations of LDLT is to carefully protect the safety of the donor[5]. If the RASD was divided, the repair would be very difficult because the duct may not dilate sufficiently in an otherwise healthy donor. The donor might then suffer severe morbidities. To reduce the donor’s risk, meticulous preoperative evaluation of the living donor’s biliary anatomy is important. The transplant surgeons must be aware of biliary anatomic variants to prevent any intraoperative bile duct injury and minimize the risk to the donor. However, there is no single examination to demonstrate all biliary conditions expeditiously. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography has some risks, such as the development of biliary injury, pancreatitis, and other conditions. MDCT is a breakthrough not only for demonstrating vascular anatomy but also to clearly depict the anatomy of the biliary system using biliary contrast material[14,15]. This modality also carries the risk of an allergic reaction. The possibility of a severe allergic reaction using vascular contrast material is only 0.04%[16]. On the other hand, biliary contrast materials have more risks of severe allergic reactions[17] and occur in up to 0.2% of patients according to the information from Japanese manufacturers. Dual enhanced MDCT is thought to be a very useful and accurate modality[14,15], but contains the relatively higher risk of an allergic reaction. Magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC) is used in the preoperative examination of donors in some institutions[18,19]. However, MRC has relatively lower spatial resolution and a thin cystohepatic duct might not be accurately depicted. Postoperatively, the donor reported in this study was examined by MRC and the RASD was observed (Figure 2). The performance of this procedure was influenced by the intraoperative findings in this patient, but also led us to use MRC routinely in the preoperative evaluation of the donor’s biliary anatomy to maximize the safety of the donors.

Figure 2 Magnetic resonance cholangiography was performed 3 mo postoperatively.

The right anterior segmental duct and cystic duct are clearly seen (arrow).

Careful intraoperative technique is also needed to improve the donor patient’s safety, by assuring appropriate management of aberrant biliary branches. IOC is an essential modality to complete the donor transplantation procedure. In many cases, IOC is performed through an incision in the cystic duct; however, it may be hazardous to incise the cystic duct in a case as reported here. Therefore, we recommend using a modified IOC, incising the area of Hartmann’s pouch. We believe that this method can reduce the possibility of injuring a very small but important biliary duct that might be not seen on preoperative imaging studies. It has been reported that IOC has some risks of allergic reactions[20], we believe that IOC itself is safe because little contrast material enters the systemic circulation. Using the knowledge gained from preoperative imaging and careful IOC, the safety of the donor is maximized.

In conclusion, to prevent injury of the bile ducts during the donor surgery of LDLT, preoperative delineation of the biliary anatomy is essential. Considering the donor’s likelihood of suffering an allergic reaction, and the spatial resolution of various imaging modalities, we recommend MRC as the ideal preoperative biliary imaging study for the donors. IOC also plays an important role in the management of these donors. To perform IOC more carefully, we recommend that Hartmann’s pouch should be incised first. By doing this we can help avoid transection of fine biliary branches that are not revealed during preoperative imaging, thus minimizing the likelihood of this avoidable complication.