Published online Jul 7, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i25.3168

Revised: March 29, 2010

Accepted: April 5, 2010

Published online: July 7, 2010

AIM: To evaluate intensity, localization and cofactors of pain in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis patients in connection with health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and disease activity.

METHODS: We reviewed and analyzed the responses of 334 patients to a specifically designed questionnaire based on the short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (SIBDQ) and the German pain questionnaire. Pain intensity, HRQOL, Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI) and colitis activity index (CAI) were correlated and verified on a visual analog scale (VAS).

RESULTS: 87.9% of patients reported pain. Females and males reported comparable pain intensities and HRQOL. Surgery reduced pain in both genders (P = 0.023), whereas HRQOL only improved in females. Interestingly, patients on analgesics reported more pain (P = 0.003) and lower HRQOL (P = 0.039) than patients not on analgesics. A significant correlation was found in UC patients between pain intensity and HRQOL (P = 0.023) and CAI (P = 0.027), and in CD patients between HRQOL and CDAI (P = 0.0001), but not between pain intensity and CDAI (P = 0.35). No correlation was found between patients with low CDAI scores and pain intensity.

CONCLUSION: Most IBD patients suffer from pain and have decreased HRQOL. Our study reinforces the need for effective individualized pain therapy in IBD patients.

- Citation: Schirbel A, Reichert A, Roll S, Baumgart DC, Büning C, Wittig B, Wiedenmann B, Dignass A, Sturm A. Impact of pain on health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(25): 3168-3177

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i25/3168.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i25.3168

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) causes inflammation of the small and large intestines. The most common symptoms are persistent bloody diarrhea, pain, weight loss and persistent fatigue. Furthermore, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)-like symptoms and depression are common in IBD[1,2]. Most patients go through periods during which symptoms flare up followed by periods of remission when symptoms subside.

In recent years, therapy of Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) has improved with the application of new drugs. Biologicals such as TNF-α inhibitors are among a new generation of therapeutic options that control symptoms and inflammation in IBD patients[3,4]. However, medical management of IBD remains challenging and cannot always control all aspects of the disease. Even with therapy, patients frequently suffer not only from diarrhea and rectal bleeding but also from abdominal pain, cramps and arthralgia. Although the established disease activity indices only include abdominal pain as one variable, pain occurs throughout the body with pain attacks severely diminishing the patient’s health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and interfering with their social and working habits[5-7]. A strong association between pain and HRQOL is well known for other diseases including neuromuscular disorders[8], rheumatoid arthritis (reviewed in[9]) and cancer[10]. Moreover, our own experience with IBD patients suffering from pain leads us to assume that in this chronic disease HRQOL is also diminished. The degree of impairment of HRQOL due to pain in IBD remains unspecified and is currently underestimated. In addition, the correlation between pain intensity, HRQOL and disease severity is poorly defined. Clearly, in order to offer individualized therapies there is a need for new tools to identify subgroups of patients who continue to suffer from pain despite anti-inflammatory and pain treatment.

The aim of this study was to evaluate pain intensity and localization in IBD patients, to correlate pain levels with HRQOL and disease severity, and to find possible associated factors on the basis of the information provided by the respondents.

We used a questionnaire based on both the standardized short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (SIBDQ), one of the most commonly used tools for evaluating HRQOL in IBD patients[11-13], and the well-established and validated German pain questionnaire[13].

In the current study we present a cross sectional analysis evaluating pain intensity, localization and cofactors and examine the relationship to HRQOL in patients with IBD. Furthermore, we correlate pain intensity levels and HRQOL to the crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI) and the colitis activity index (CAI), both of which are well-established scores for evaluating current disease activity[14,15].

This cross sectional study investigated the relationship between pain experience and HRQOL as well as disease activity indices in patients with IBD. Our multicenter survey was performed during the period 2005-2007 on patients attending the outpatient clinics at three independent campuses of Charité Medical School, Campus Virchow (45%), Campus Mitte (28%) and Campus Benjamin Franklin (27%), where all patients were asked to participate. Inclusion criteria were: (1) patients (aged 18-80 years) who signed informed consent; (2) patients with an endoscopically and histologically confirmed diagnosis of CD or UC of at least 6 mo, independent of clinical activity and extent of the disease; and (3) to analyze pain and HRQOL in patients who had undergone abdominal surgery, we included patients with small or large intestinal resection due to IBD.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) patients with indeterminate colitis or microscopic colitis; and (2) patients with only surgically drained cutaneous abscesses or fistula draining were excluded from subgroup analysis for surgery.

Patient medical records were checked for disease phenotype, disease duration, medication, and concomitant diseases. The survey was approved by the local ethics committee of the Charité Berlin. Since mechanisms of pain in CD and UC may differ, we analyzed most results for each IBD type separately. As a control, a group of 100 age-matched healthy individuals without complaints or medical history were asked to complete the SIBDQ. Aiming to provide a control group with comparable data, we also used the disease-specific questionnaire for the healthy control group.

To cover all aspects of pain, HRQOL, and the possible factors influencing patients’ perception of pain, we developed a new questionnaire, based on the SIBDQ and the validated German pain questionnaire[13,16,17]. Out of the 25 items in the German pain questionnaire, 12 were taken for the current questionnaire (we removed items 6, 8, parts of 10 and 11; 12, 13, 16, 17, 19, 20, 23, 24, 25, module D, parts of module S, and module V). The first part of our questionnaire collected 50 single variables based on the German pain questionnaire and extended these to include demographic parameters (age, gender, working conditions), medical history (time of first diagnosis, course of disease with indication of fistula or stenosis, active disease or clinical remission), IBD-related symptoms (stool frequency, bloody stools, fever), pain characteristics (localization, duration, intensity, impairment due to pain), pain therapy and the use of other drugs (including anti-depressants), lifestyle (eating habits, smoking, use of complementary medicine) and quality of life. Pain intensity was evaluated on the basis of a visual analog scale (VAS)[18]. Patients indicated their scores on a 100 mm horizontal line, where the left end point of the line was marked “no pain” (= 0 mm) and the right end point was marked “strongest imaginable pain” (= 100 mm). Patients were asked to document their symptoms over a sustained period, in this case the previous week. The patients’ statements were matched with information from the medical records.

The second part of the questionnaire comprised the SIBDQ, a widely accepted and standardized disease-specific health-related quality of life questionnaire for patients with CD and UC, which is composed of 10 questions each with 7 possible responses[11,12]. We used the SIBDQ because it yields results comparable to those obtained with the full 32-item IBDQ for measuring HRQOL in patients with IBD[19]. A maximum of 7 points could be scored on each question. A score of 70 indicated the highest HRQOL, whereas the lower scores indicated lower HRQOL. The questionnaire is recognized as a reliable and sensitive tool for determining health-related quality of life[7]. Both the German pain questionnaire and the SIBDQ are validated[13,16,17].

To analyze the correlation between pain intensity, HRQOL and disease activity, we collected the CDAI and CAI (according to Rachmilewitz)[20] and matched them with pain intensity and HRQOL. The CDAI consists of eight variables (stool frequency, abdominal pain, general well-being, complications, hematocrit, use of loperamide, body weight, presence of abdominal mass), each summed after adjustment with a weighting factor. CD remission is defined as a CDAI score of less than 150. Severe disease is defined as a value greater than 450[21]. Most major research studies on the use of medications in CD use the CDAI as the gold standard[22-24].

For UC the patient’s overall evaluation of symptoms was assessed according to the Rachmilewitz’s Clinical Activity Index (CAI)-a well established index with good validity and reliability[20,25]. The score considers the number of bloody stools, abdominal pain and cramping, frequency of incontinence and the need for anti-diarrheal drugs, and an assessment of general well-being. Clinical remission was defined as a CAI < 3. Increased mild to moderate disease activity was defined as CAI = 4-9 and relapse was defined as CAI ≥ 10[26,27].

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 13.0) and SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). These included means and standard deviations. The χ2 test was used to analyze discrete variables. The Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskal-Wallis test were used to compare quantitative results between groups. For correlation analysis, the bivariate Pearson correlation was used. The accepted level of statistical significance was 5% (P < 0.05). The effect of several factors on HRQOL was examined by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). Results are presented as adjusted means with 95% confidence intervals for categorical variables, and regression coefficient estimates for continuous variables.

Four hundred patients were asked to participate in the study, 387 (96.8%) filled out the questionnaire. Of these, 53 questionnaires were incomplete and were thus excluded. 334 (86.3%) questionnaires were included in the further study. CD had been diagnosed in 179 (53.6%) and UC in 155 (46.4%) patients. Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of all the study participants.

| Demographics | CD | UC |

| Total | 179 | 155 |

| Age, mean, (SD), [range], yr | 38.9 (± 11.6) [18-71.6] | 39.8 (± 13.7) [18.6-75.5] |

| Age at disease onset, mean, (median), [interquartile range], yr | 28 (24.5) [14] | 31.6 (29.2) [16.2] |

| Age in males | 28.9 (± 11.7) [12.6-70.7] | 32.6 (± 12.2) [10.3-66.7] |

| Age in females | 27.5 (± 12.0) [6.2-72.9] | 30.6 (± 12.6) [11.8-70.6] |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 71 (39.6%) | 71 (45.8%) |

| Female | 108 (60.3%) | 84 (54.2%) |

| IBD | ||

| Disease duration mean, (median), [inter quartile range], yr | 10.9 (9.2) [12.8] | 8.4 (6.7) [9.9] |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | ||

| Arthralgia | 102 | 79 |

| Uveitis | 6 | 2 |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 0 | 5 |

| Pyoderma gangraenosum | 2 | 3 |

| Erythema nodosum | 3 | 0 |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 0 | 1 |

| Autoimmune hemolytic anemia | 0 | 1 |

| CD-associated polyneuropathy | 1 | - |

| Pulmonary manifestations | 1 | 0 |

| Current medication (% of users) | ||

| Prednisolone | ||

| Total | 37.7 | 41.3 |

| Systemic | 25.7 | 32.7 |

| Local | 13.7 | 11.3 |

| Local and systemic | 1.7 | 2.7 |

| 5-Aminosalicylates | ||

| Total | 26.3 | 70.7 |

| Local | 1.1 | 3.3 |

| Immunosuppressants | ||

| Total | 54.9 | 30.0 |

| Azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine | 46.9 | 26.4 |

| 6-MP | 2.9 | 4.0 |

| Methotrexate | 2.3 | 1.3 |

| Tacrolimus | 0.6 | 4.0 |

| TNF-α-inhibitors | 9.1 | 0.7 |

| Analgesics | ||

| Total | 29.1 | 20.7 |

| No information | 25.1 | 32.7 |

| Mean IBD severity, mean, (median), [interquartile range] | ||

| CDAI | 173 (166) [186] | |

| CAI | 5.08 (4.5) [5] | |

| SIBDQ, mean, (median), [interquartile range] | 48.3 (49) [21] | 46.7 (47) [21] |

| Males | 49.6 (51) [25] | 48.9 (48) [22] |

| Females | 47.4 (48) [19] | 44.5 (45) [19] |

| SIBDQ healthy controls | 58.5 (59) [10] |

In our survey 12.1% of patients reported no pain, 39.7% only had pain during flare-ups, and 48.2% mentioned persistent pain. Patients reported different durations of pain attacks ranging from seconds (17.4%), minutes (44.8%), or hours (27.4%) to days (10.4%). When asked to specify what time of day the pain occurred, 66.8% of patients reported pain unrelated to the time of day, 14.5% had pain only before noon, 14.9% during daylight hours, and 16.5% only at night. The latter group was associated with significantly lower HRQOL (P = 0.016).

A comparison of pain intensities and HRQOL between males and females revealed no difference (P = 0.073 and P = 0.6, respectively).

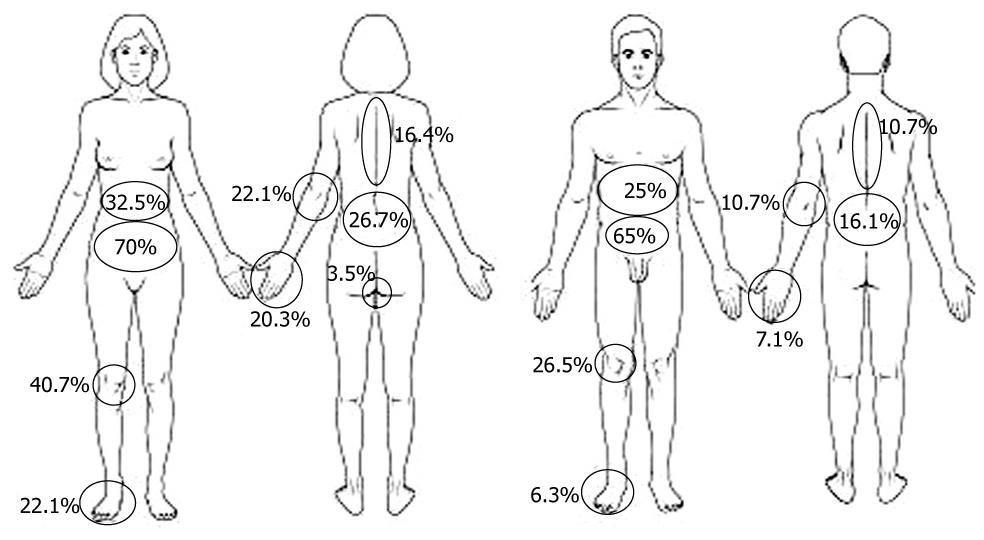

All indicated pain localizations are depicted in Figure 1 and were significantly different in males and females, with females complaining more often of arthralgia. Most patients indicated more than one pain site: 2 pain sites (18.6%), 3 pain sites (11.5%), 4 pain sites (13.6%), 5 pain sites (9.1%), and > 5 pain sites (17.7%). 39% of the patients described the pain as superficial, 61% as “deep insight”. Multivariate analysis showed that pain intensity significantly reduced HRQOL (P < 0.0001), independently of sex, pain localization or disease activity.

Although we did not evaluate present disease location, a comparison of pain localization in CD and UC patients revealed higher pain frequency in the right upper abdomen in CD than in UC (39.2% vs 18.9%), although for abdominal pain in general there was no statistically significant difference between CD and UC. In contrast, in UC patients, lower left abdominal pain was statistically more frequent (76.4% vs 55.6%) than in CD patients. The lower left abdomen was the pain site that significantly influenced (P = 0.0002) HRQOL, independent of other factors (Table 2). Interestingly, although arthralgia was not different between CD and UC, CD patients complained more often about pain in hips, knees, and hands.

| Variable | Mean (95% CI)1 | P value |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 45.3 (43.0-47.6) | 0.607 |

| Male | 46.1 (43.4-48.8) | |

| EIM | ||

| Yes | 48.1 (46.0-47.7) | 0.004 |

| No | 43.3 (40.2-46.4) | |

| Pain LUQ | ||

| Yes | 44.6 (41.1-48.2) | 0.398 |

| No | 46.8 (43.9-50.0) | |

| Pain LLQ | ||

| Yes | 43.0 (41.0-45.6) | 0.001 |

| No | 48.3 (45.6-51.1) | |

| Pain RUQ | ||

| Yes | 46.5 (43.2-49.8) | 0.511 |

| No | 44.8 (41.6-48.1) | |

| Pain RLQ | ||

| Yes | 45.5 (43.1-47.8) | 0.778 |

| No | 45.9 (43.0-48.8) | |

| GI-related surgeries | ||

| Yes | 46.0 (42.7-49.3) | 0.738 |

| No | 45.4 (43.1-47.6) | |

| Variable | Regression coefficient estimate2 | P value |

| Age (yr) | 0.075 | 0.244 |

| IBD duration (mo) | 0.004 | 0.635 |

| Pain intensity (0-100 mm)3 | -1.734 | < 0.0001 |

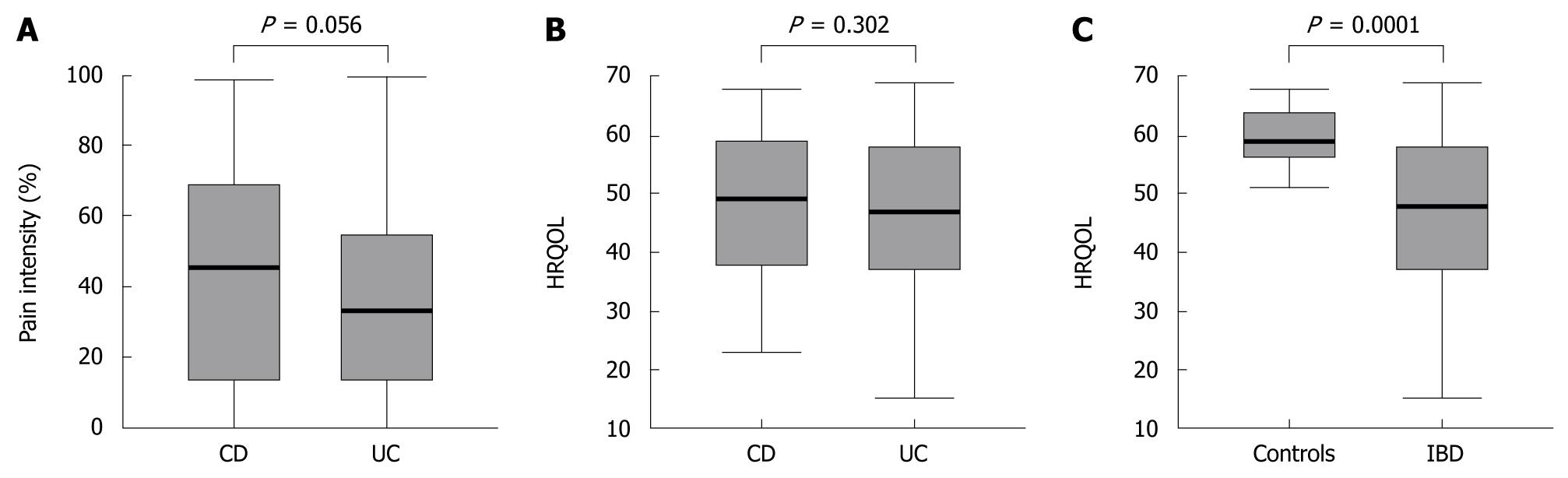

Pain levels in CD and UC patients were not significantly different (P = 0.056) and HRQOL scores were comparable (P = 0.302) (Figure 2A and B). Compared to healthy controls, HRQOL was significantly reduced in IBD patients (SIBDQ of healthy controls (P < 0.0001), regardless of whether they had CD or UC (Figure 2C).

A separate sub-analysis of CD and UC patients with abdominal pain or joint pain showed that HRQOL in UC patients was not significantly impaired by abdominal or joint pain (P = 0.17 and P = 0.52, respectively). In contrast, HRQOL in CD patients was significantly reduced by abdominal pain (P = 0.01) but not by joint pain (P = 0.09).

Having assessed pain intensity and HRQOL in IBD patients in general, we next assessed cofactors affecting pain and HRQOL. Pain was intensified in 38.3% of patients by mental stress, in 28.1% by ingestion of food, in 18.9% by physical activity, in 12.0% by the consumption of coffee, tobacco, or alcohol, in 9.9% by weather change, and in 7.2% by resting. In 22.9% of female patients, increased pain was associated with menses. Only 47.3% of patients declared their smoking status and remaining data were not statistically significantly different. Only 12 patients (3.6%, 7 UC, 5 CD, 9 female and 3 male) had depression.

In our study, 44.9% of patients had extraintestinal manifestations (EIM), including cutaneous manifestations, uveitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, arthralgia or autoimmune hemolytic anemia (Table 1). Eighty-seven percent of patients with EIM complained of arthralgia. Patients indicated whether they had ever had or currently had EIM. Data were matched with medical records. As expected, patients with EIM had significantly more pain than patients without EIM (P = 0.001), irrespective of whether they had CD (P = 0.001) or UC (P = 0.001). Patients with EIM also had significantly lower HRQOL than patients without EIM (P = 0.001), again regardless of whether they had CD (P = 0.005) or UC (P = 0.038). Multivariate analysis revealed that EIM significantly (P = 0.0052) reduced HRQOL, independent of other variables (Table 2).

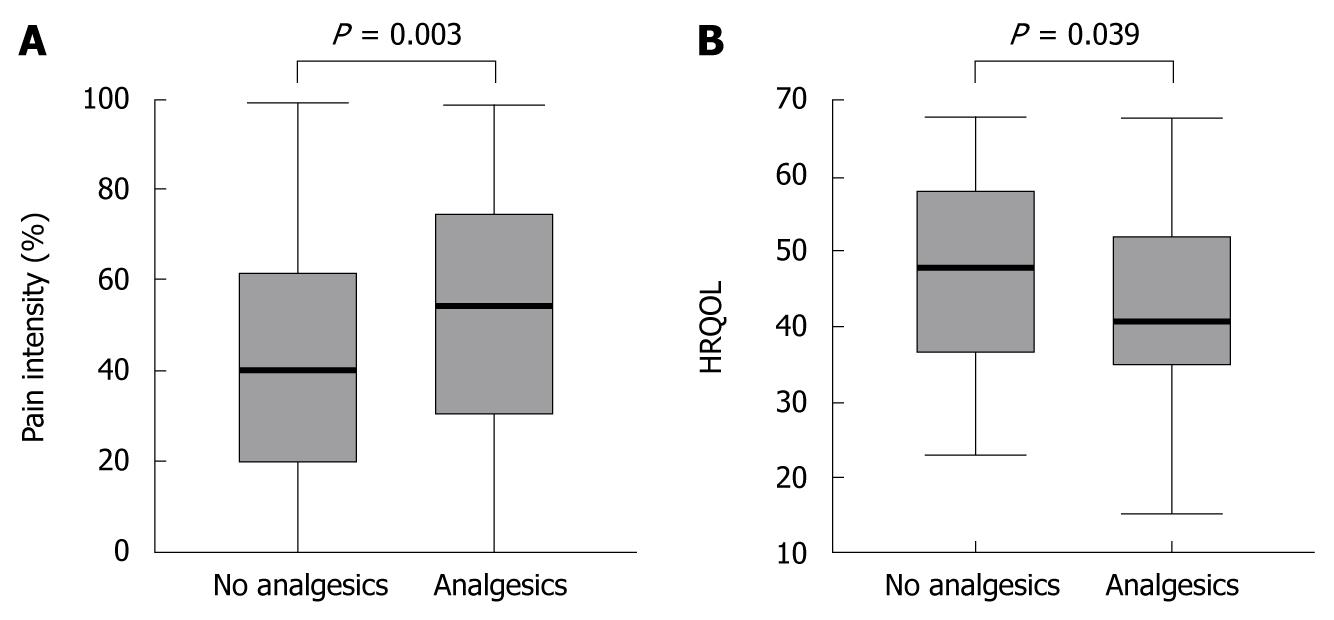

In our study, 25.1% of all patients and 29.0% of patients reporting pain used analgesics. A difference between females and males was identified: 30.3% of females but only 18.0% of males took analgesics (P = 0.033). In CD, 29.1% of patients used analgesics, whereas in UC only 20.7% used analgesics (P = 0.013) (35.8% of females with CD, 18.2% of males with CD, 22.8% of females with UC, 18.3% of males with UC). Within the group of patients taking analgesics, 47.7% used morphine derivatives for no longer than 4 wk, 44.2% used metamizole (a pyrazolone derivative), and 20.9% took non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID). Additionally, 5.8% of patients received antidepressants, some for pain modification and some for depression.

To evaluate the efficacy of analgesic drugs in IBD, we only included patients reporting pain for further investigation. As depicted in Figure 3A, patients taking analgesics still had higher pain intensities than patients not receiving analgesic treatment (P = 0.003). Accordingly, patients on analgesics reported decreased HRQOL (P = 0.039) (Figure 3B).

In our analysis, 24% of patients had undergone surgery due to IBD (41.5% of CD and 8.0% of UC patients). To obtain information on whether abdominal surgery modified pain intensity or HRQOL in IBD, we included all patients who had undergone abdominal surgery in the subsequent analysis, irrespective of pain status. Patients without prior surgery were excluded from this sub-analysis.

Patients who had undergone IBD-related abdominal surgery had significantly lower pain intensity than patients who had not had surgery (P = 0.023), whereas HRQOL was not significantly different in patients with or without surgery (P = 0.73) (Table 2).

Interestingly, when analyzing IBD, regardless of whether CD or UC, we identified significant gender differences in the correlation between pain and HRQOL. Pain intensity in females was lower (P = 0.001) and HRQOL significantly higher (P = 0.03) after surgery, whereas this correlation was not observed for males.

Since CD and UC require different types of surgery, we next analyzed the correlation between surgery for CD and UC separately. CD patients benefited from surgery as pain intensity was significantly reduced (P = 0.036), however, their HRQOL remained unchanged (P = 0.466). In UC patients who had undergone surgery, pain levels (P = 0.095) and HRQOL (P = 0.305) did not differ from those of UC patients who had not had surgery. Considering all abdominal surgeries including non IBD-related surgeries like appendectomy (36), hysterectomy (9), ovariectomy (8), C-section (4), cholecystectomy (11), inguinal hernia revision (5), sterilization (7) and liver transplantation (1) there was no difference in pain intensity or HRQOL.

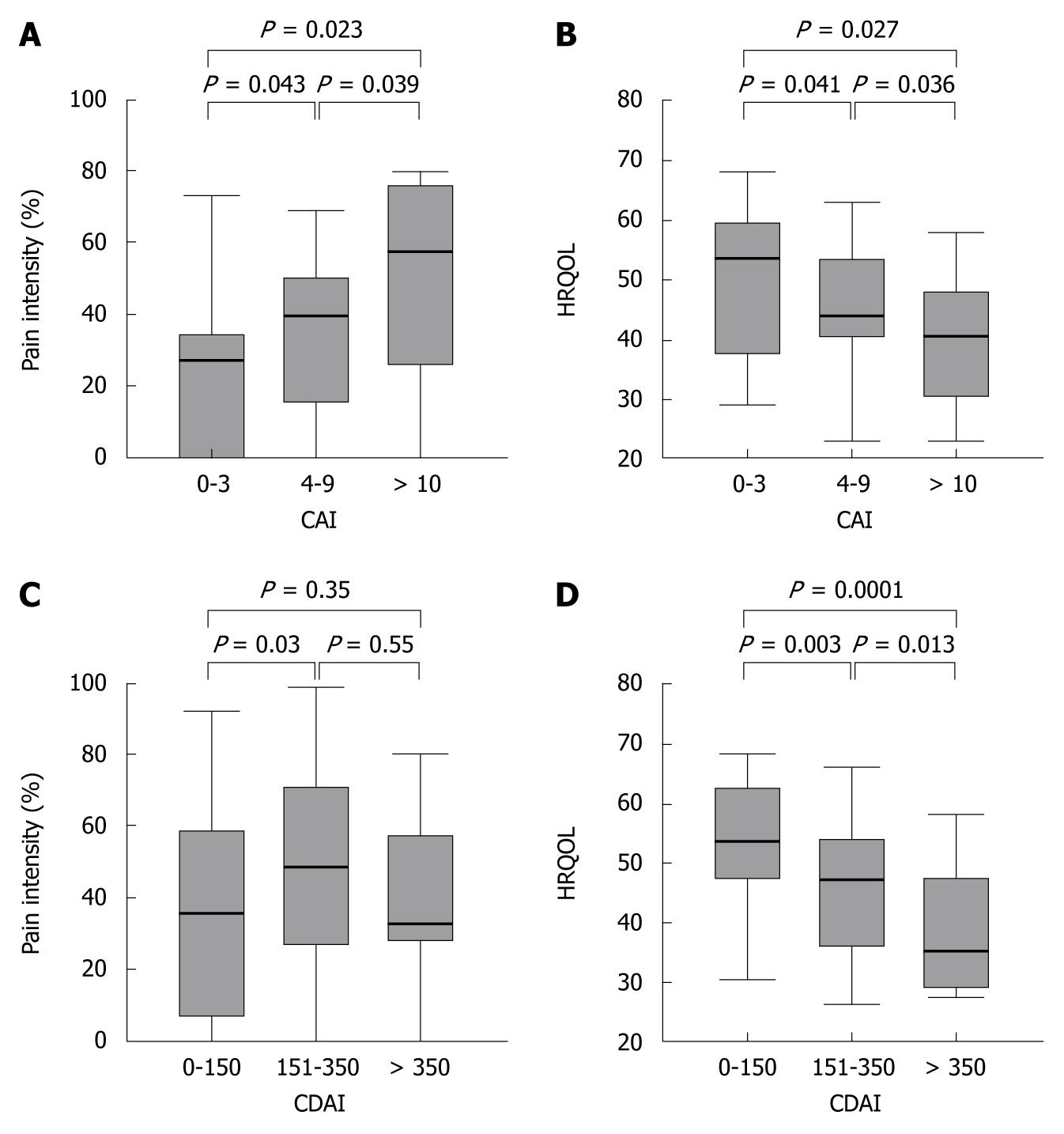

To assess whether disease activity indices correlate with pain intensity or HRQOL, we examined the relationship between CAI, CDAI, pain intensity and HRQOL. When separating UC patients according to their disease activity index (CAI < 4 = remission; CAI 4-9 = increased disease activity; CAI ≥ 10 = flare-up), pain intensity increased and the HRQOL dropped with increased disease activity (Figure 4A and B).

In contrast to UC patients, in the overall CD population the disease activity did not correlate with pain intensity (r = 0.23). When analyzing subgroups according to the CDAI level, this lack of correlation was due to the relative high pain levels in the patient group despite remission (based on a CDAI ≤ 150). However, in CD patients with a CDAI > 150, CDAI and pain levels correlated significantly (r = 0.55, P = 0.002). As in UC, in CD patients the CDAI correlated well with the HRQOL (r = 0.53, P < 0.0001), and increased pain intensities correlated with decreased HRQOL (r = 0.58, P < 0.0001) (Figure 4C and D). Interestingly, in both CD and UC higher disease activity levels were associated with the presence of EIM (P = 0.04 for both).

To optimize patient management in IBD, health care personnel not only need to know the type, localization and intensity of CD or UC to offer the best possible therapy, they also need to acknowledge that pain and impaired HRQOL is a great burden in the lives of IBD patients. Furthermore, we have to consider that anti-inflammatory therapy is not equal to pain management or improvement of HRQOL. However, to date, a systematic analysis of duration, localization and associated factors of pain and a subsequent correlation with major variables in the disease course and HRQOL is still lacking. To address this situation our study aimed to: (1) evaluate pain intensity and localization in IBD; (2) compare the results with HRQOL; and (3) explore whether pain levels and HRQOL are related to disease severity or other factors. This kind of study is timely and of special importance since treatment of patients should not only involve mucosal healing but should consider the patient as a whole.

In our study, the number of patients suffering from pain was very high (87.9%). Since we are a reference center with mostly pre-selected patients with more complex and severe disease courses, these high pain levels might be explained by referral bias. On stratifying pain levels for CD and UC separately, our data revealed that pain levels in patients with CD and UC were not significantly different, confirming the results of Heikenen and coworkers, who found similar results in children with IBD[28].

Although multivariate analysis revealed no gender differences in pain intensity or HRQOL, an analysis of a subgroup of patients who had undergone surgery showed that HRQOL was significantly lower in females, verifying that pain levels and HRQOL do not necessarily correlate[29,30]. In addition, females more often took analgesics indicating that they may be more affected by pain than males. Another explanation for the lower HRQOL in females could be a difference in pain perception with more attention to pain in females or different pain-coping mechanisms. Since IBS-like symptoms, depression and anxiety are more frequent in female than in male IBD patients[31,32], this could be an additional explanation for the gender difference in HRQOL.

Underlining the differences between male and female IBD patients, pain localization also differed between genders, with females complaining of significantly more arthralgia. As severe joint pain impacts the mobility of patients, the increased projection of pain in the joints in females might contribute to explaining their decreased HRQOL compared to male IBD patients. Interestingly, Palm and coworkers also found impaired HRQOL in IBD patients with non-inflammatory joint pain compared to IBD patients without joint pain, but they did not find a difference between females and males[33].

Sub-analysis of IBD type revealed differences in pain localization and corresponding HRQOL. Interestingly, in UC patients HRQOL was not significantly impaired by abdominal pain or arthralgia, whereas in CD patients, abdominal pain reduced HRQOL significantly.

Localization of pain is a matter of great interest because of the different treatment options for abdominal pain and arthralgia. While the treatment of arthralgia could be composed of physical therapy, steroids or sulfasalazine, abdominal pain requires a more effective anti-inflammatory therapy. In cases of persistent pain despite remission, IBS-like symptoms, depression or drug-related side effects must also be considered.

A multivariate analysis revealed that HRQOL is not only impaired by pain intensity but also pain localization, the presence of EIM and disease activity influences HRQOL independently of each other and other variables.

Pain can be perceived very differently and its duration varies individually. Given the chronic nature of IBD, nearly half of the patients reporting pain suffered pain irrespective of current disease activity. Accordingly, and in contrast to the pain character reported by patients with IBS, most IBD patients’ pain was unrelated to the time of day. However, clearly correlating with disturbed nighttime sleep, patients suffering from pain mostly at night had significantly lower HRQOL, indicating the necessity for increased pain relief therapy in the evening in this group.

More than 40% of IBD patients have EIM of their disease[34,35]. This was confirmed by our study; 44.9% of our patients had EIM, manifesting most frequently as joint pain. Females had significantly more EIM than males (P = 0.001). Spondyloarthropathy is the most frequent extraintestinal complication of IBD and is associated with pain and stiffness[36]. Therefore, it was not surprising that patients with EIM had significantly more pain (P = 0.001) and significantly lower HRQOL than patients without EIM. EIM in IBD are frequent and play an important role in disease management[37]. The overall incidence of EIM in IBD ranges from 25% to 36%, with more than 60 different manifestations. Rheumatoid extraintestinal manifestations are frequent in patients with CD (38%) and UC (30%)[38,39].

In our study, less than one third of the patients reporting pain took analgesics. Interestingly, although their pain levels were comparable, females more frequently used analgesics than males. Whether or not this suggests a gender-specific approach to pain or pain killers, or a greater fear of side effects, this significant difference indicates the need to individualize pain therapy. Current pain therapy seems to be ineffective and, in addition, pain perception differs in each individual, which is illustrated by the fact that patients taking pain killers still complained of more pain than patients who reported pain but were not receiving pain treatment.

The use of analgesics and their dosage is difficult to gauge and should be well evaluated. Pain killers have a variety of known effects and side effects. Given the gastrointestinal side effects and the possibility of aggravating mucosal inflammation, NSAR should be avoided in IBD. However, opioids might also worsen pain in IBD patients because long-term use of opioids may also be associated with the development of abnormal sensitivity to pain and a progressive decline in plasma cortisol levels[40]. Consequently, Smith and coworkers recently showed that treatment with naltrexone improved disease course and HRQOL of CD patients[41]. An alternative explanation for the discrepancy between use of analgesics and perception of pain might be the high prevalence of functional somatic symptoms (IBS-like symptoms) among IBD patients[2].

Surgery is an important therapeutic component in the course of IBD. During their lifetime more than 55% of IBD patients undergo abdominal surgery[42-45]. Surgery is often used as a last resort in severe cases with disease complications or in patients who do not respond adequately to therapy. In our study, particularly female CD patients who had undergone IBD-related surgery had significantly lower pain levels and higher HRQOL compared to patients who had not had surgery. Although this phenomenon might be a reflection of the selected patient population treated at university clinics, the observed improvement in HRQOL was confirmed in other studies on CD[46-48] as well as on UC[49] where the disease-related symptoms improved after surgery. In addition, performance of non IBD-related surgeries did not alter pain intensity or HRQOL.

Not surprisingly, we confirmed that compared to healthy individuals HRQOL was significantly decreased in IBD patients[13,50] and correlated with the respective disease activity scores[51]. Most previous clinical studies determined a positive effect of different substances in the treatment of IBD on disease activity and therefore HRQOL[52]. Contrastingly, in our study population disease activity correlated with pain levels in UC patients, but not in CD patients. CD patients, in particular, indicated pain despite low or moderate CDAI scores. This new perception may be due to the dominance of other factors that influence the CDAI, such as EIM or fistulizing disease course, and the underrepresentation of pain in this disease activity index, whereas in the CAI indication of pain is weightier for the complete score. In addition, as mentioned before, IBS-like symptoms, depression or drug-related side effects could cause pain without increased disease activity. Therefore, it is very important to have this new questionnaire in addition to the commonly used disease activity indices to measure pain as a strong impact factor for HRQOL in patients with IBD. The new combined questionnaire contains some questions that have not been validated before, which might affect interpretation of the results.

The strength of our study is its combined analysis of physiological complaints and parameters relevant to HRQOL, but it also has limitations. First, our study population consisted of referred patients who may have more complex and severe disease courses and higher pain levels compared to other IBD patient cohorts with more moderate disease courses.

Second, the cross sectional design of this study prohibits any determination in causality of analyzed factors or process of disease due to certain circumstances. Moreover, although we measured many potential modifiers of pain, the descriptive design allows for possible influence by unknown and unmeasured confounders.

Third, we did not evaluate anxiety or depression, conditions which can worsen the disease course and influence pain perception and HRQOL[1]. Nor did we evaluate disease phenotype according to the Montreal classification, which would have allowed a better correlation with pain localization. Nevertheless, we believe that our data will encourage physicians to devise patient-specific therapy plans for a subgroup of patients suffering from pain independent of disease activity.

In conclusion, most IBD patients suffer from pain and have decreased HRQOL. Duration and localization vary widely and differ not only between CD and UC patients, but also between genders. Most interestingly, our data point out that pain levels and HRQOL do not necessarily correlate with disease activity. By using this newly designed questionnaire we now bring to light that the CDAI does not sufficiently consider pain as a major limitation of HRQL in IBD. On the other hand, when defining the absence of diarrhea and pain as true remission, a CDAI below 150 might not indicate remission in the perception of a CD patient. Our results focus new attention on currently insufficient pain therapy in IBD patients and stress the need for sufficient and continually reviewed individualized pain therapy. Whether this insufficient pain therapy is due to the inadequate effect of pain killers, additional IBS-like symptoms, underrepresented complaints of pain, or physicians’ underestimation of pain intensity remains unclear and will require further studies.

Despite recent advances in the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), acute and chronic pain continues to have a profound negative impact on patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Moreover, the methods for evaluating pain and its impact on HRQOL in IBD patients are still insufficient.

The development of a new questionnaire based on both the short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (SIBDQ) and the German pain questionnaire enabled us to investigate localization and levels of pain and their impact on HRQOL in IBD patients. Many clinical studies have been performed to investigate the effect of anti-inflammatory therapies on HRQOL but there are no data available on the correlation of pain and HRQOL.

This study provides the first evidence that the majority of IBD patients suffer from pain despite anti-inflammatory therapy and that HRQOL is impaired by pain. Interestingly, ulcerative colitis pain and HRQOL are well correlated with disease activity, whereas Crohn’s disease patients also suffer from pain during remission.

This study focuses new attention on pain as a burden to patients and urges physicians to devise sufficient and individualized pain therapy plans to improve patients’ HRQOL.

There is increasing focus upon QOL in patients with chronic IBD, and upon factors determining and modifying this. Pain is a frequent symptom in IBD, and may contribute adversely to QOL in these patients.

Peer reviewer: Andrew S Day, MB, ChB, MD, FRACP, AGAF, Associate Professor, Department of Paediatrics, University of Otago, Christchurch, PO Box 4345, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Graff LA, Walker JR, Bernstein CN. Depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease: a review of comorbidity and management. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1105-1118. |

| 2. | Grover M, Herfarth H, Drossman DA. The functional-organic dichotomy: postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease-irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:48-53. |

| 3. | Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and established and evolving therapies. Lancet. 2007;369:1641-1657. |

| 4. | Clark M, Colombel JF, Feagan BC, Fedorak RN, Hanauer SB, Kamm MA, Mayer L, Regueiro C, Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ. American gastroenterological association consensus development conference on the use of biologics in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease, June 21-23, 2006. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:312-339. |

| 5. | Blondel-Kucharski F, Chircop C, Marquis P, Cortot A, Baron F, Gendre JP, Colombel JF. Health-related quality of life in Crohn's disease: a prospective longitudinal study in 231 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2915-2920. |

| 6. | Casellas F, López-Vivancos J, Badia X, Vilaseca J, Malagelada JR. Influence of inflammatory bowel disease on different dimensions of quality of life. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:567-572. |

| 7. | Irvine EJ. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease and other chronic diseases. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1996;221:26-28. |

| 8. | Padua L, Aprile I, Frusciante R, Iannaccone E, Rossi M, Renna R, Messina S, Frasca G, Ricci E. Quality of life and pain in patients with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2009;40:200-205. |

| 9. | Jakobsson U, Hallberg IR. Pain and quality of life among older people with rheumatoid arthritis and/or osteoarthritis: a literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2002;11:430-443. |

| 10. | Fujimura T, Takahashi S, Kume H, Takeuchi T, Kitamura T, Homma Y. Cancer-related pain and quality of life in prostate cancer patients: assessment using the Functional Assessment of Prostate Cancer Therapy. Int J Urol. 2009;16:522-525. |

| 11. | Han SW, Gregory W, Nylander D, Tanner A, Trewby P, Barton R, Welfare M. The SIBDQ: further validation in ulcerative colitis patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:145-151. |

| 12. | Jowett SL, Seal CJ, Barton JR, Welfare MR. The short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire is reliable and responsive to clinically important change in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2921-2928. |

| 13. | Rose M, Fliege H, Hildebrandt M, Körber J, Arck P, Dignass A, Klapp B. [Validation of the new German translation version of the "Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire" (SIBDQ)]. Z Gastroenterol. 2000;38:277-286. |

| 14. | Yoshida EM. The Crohn's Disease Activity Index, its derivatives and the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire: a review of instruments to assess Crohn's disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 1999;13:65-73. |

| 15. | Acciuffi S, Ghosh S, Ferguson A. Strengths and limitations of the Crohn's disease activity index, revealed by an objective gut lavage test of gastrointestinal protein loss. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10:321-326. |

| 16. | Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006;10:287-333. |

| 17. | Nagel B, Gerbershagen HU, Lindena G, Pfingsten M. [Development and evaluation of the multidimensional German pain questionnaire]. Schmerz. 2002;16:263-270. |

| 18. | Wewers ME, Lowe NK. A critical review of visual analogue scales in the measurement of clinical phenomena. Res Nurs Health. 1990;13:227-236. |

| 19. | Irvine EJ, Zhou Q, Thompson AK. The Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT Investigators. Canadian Crohn's Relapse Prevention Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1571-1578. |

| 20. | Rachmilewitz D. Coated mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid) versus sulphasalazine in the treatment of active ulcerative colitis: a randomised trial. BMJ. 1989;298:82-86. |

| 21. | Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW, Kern F Jr. Development of a Crohn's disease activity index. National Cooperative Crohn's Disease Study. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:439-444. |

| 22. | Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf DC, Olson A, Bao W. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn's disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541-1549. |

| 23. | Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SB, Rutgeerts P, Fedorak RN, Lukas M, MacIntosh DG, Panaccione R, Wolf D, Kent JD, Bittle B. Adalimumab for maintenance treatment of Crohn's disease: results of the CLASSIC II trial. Gut. 2007;56:1232-1239. |

| 24. | Schreiber S, Khaliq-Kareemi M, Lawrance IC, Thomsen OØ, Hanauer SB, McColm J, Bloomfield R, Sandborn WJ. Maintenance therapy with certolizumab pegol for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:239-250. |

| 25. | Turner D, Seow CH, Greenberg GR, Griffiths AM, Silverberg MS, Steinhart AH. A systematic prospective comparison of noninvasive disease activity indices in ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1081-1088. |

| 26. | Kruis W, Schreiber S, Theuer D, Brandes JW, Schütz E, Howaldt S, Krakamp B, Hämling J, Mönnikes H, Koop I. Low dose balsalazide (1.5 g twice daily) and mesalazine (0.5 g three times daily) maintained remission of ulcerative colitis but high dose balsalazide (3.0 g twice daily) was superior in preventing relapses. Gut. 2001;49:783-789. |

| 27. | Kruis W, Bar-Meir S, Feher J, Mickisch O, Mlitz H, Faszczyk M, Chowers Y, Lengyele G, Kovacs A, Lakatos L. The optimal dose of 5-aminosalicylic acid in active ulcerative colitis: a dose-finding study with newly developed mesalamine. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1:36-43. |

| 28. | Heikenen JB, Werlin SL, Brown CW, Balint JP. Presenting symptoms and diagnostic lag in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1999;5:158-160. |

| 29. | Bernklev T, Jahnsen J, Henriksen M, Lygren I, Aadland E, Sauar J, Schulz T, Stray N, Vatn M, Moum B. Relationship between sick leave, unemployment, disability, and health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:402-412. |

| 30. | Saibeni S, Cortinovis I, Beretta L, Tatarella M, Ferraris L, Rondonotti E, Corbellini A, Bortoli A, Colombo E, Alvisi C. Gender and disease activity influence health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel diseases. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:509-515. |

| 31. | Kovács Z, Kovács F. Depressive and anxiety symptoms, dysfunctional attitudes and social aspects in irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2007;37:245-255. |

| 32. | Jones MP, Bratten J, Keefer L. Quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome differs between subjects recruited from clinic or the internet. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2232-2237. |

| 33. | Palm Ø, Bernklev T, Moum B, Gran JT. Non-inflammatory joint pain in patients with inflammatory bowel disease is prevalent and has a significant impact on health related quality of life. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1755-1759. |

| 34. | Veloso FT, Carvalho J, Magro F. Immune-related systemic manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. A prospective study of 792 patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;23:29-34. |

| 35. | Lakatos L, Pandur T, David G, Balogh Z, Kuronya P, Tollas A, Lakatos PL. Association of extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease in a province of western Hungary with disease phenotype: results of a 25-year follow-up study. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2300-2307. |

| 36. | Salvarani C, Fries W. Clinical features and epidemiology of spondyloarthritides associated with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2449-2455. |

| 37. | Rankin GB. Extraintestinal and systemic manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Med Clin North Am. 1990;74:39-50. |

| 38. | Orchard TR, Wordsworth BP, Jewell DP. Peripheral arthropathies in inflammatory bowel disease: their articular distribution and natural history. Gut. 1998;42:387-391. |

| 39. | Brynskov J, Binder V. Arthritis and the gut. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:997-999. |

| 40. | Ballantyne JC, Mao J. Opioid therapy for chronic pain. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1943-1953. |

| 41. | Smith JP, Stock H, Bingaman S, Mauger D, Rogosnitzky M, Zagon IS. Low-dose naltrexone therapy improves active Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:820-828. |

| 42. | Vind I, Riis L, Jess T, Knudsen E, Pedersen N, Elkjaer M, Bak Andersen I, Wewer V, Nørregaard P, Moesgaard F. Increasing incidences of inflammatory bowel disease and decreasing surgery rates in Copenhagen City and County, 2003-2005: a population-based study from the Danish Crohn colitis database. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1274-1282. |

| 43. | Wolters FL, Joling C, Russel MG, Sijbrandij J, De Bruin M, Odes S, Riis L, Munkholm P, Bodini P, Ryan B. Treatment inferred disease severity in Crohn's disease: evidence for a European gradient of disease course. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:333-344. |

| 44. | Jess T, Riis L, Vind I, Winther KV, Borg S, Binder V, Langholz E, Thomsen OØ, Munkholm P. Changes in clinical characteristics, course, and prognosis of inflammatory bowel disease during the last 5 decades: a population-based study from Copenhagen, Denmark. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:481-489. |

| 45. | Cosnes J, Nion-Larmurier I, Beaugerie L, Afchain P, Tiret E, Gendre JP. Impact of the increasing use of immunosuppressants in Crohn's disease on the need for intestinal surgery. Gut. 2005;54:237-241. |

| 46. | da Luz Moreira A, Stocchi L, Remzi FH, Geisler D, Hammel J, Fazio VW. Laparoscopic surgery for patients with Crohn's colitis: a case-matched study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1529-1533. |

| 47. | Yazdanpanah Y, Klein O, Gambiez L, Baron P, Desreumaux P, Marquis P, Cortot A, Quandalle P, Colombel JF. Impact of surgery on quality of life in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1897-1900. |

| 48. | Tillinger W, Mittermaier C, Lochs H, Moser G. Health-related quality of life in patients with Crohn's disease: influence of surgical operation--a prospective trial. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:932-938. |

| 49. | Köhler LW, Pemberton JH, Zinsmeister AR, Kelly KA. Quality of life after proctocolectomy. A comparison of Brooke ileostomy, Kock pouch, and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:679-684. |

| 50. | Poghosyan T, Polliand C, Bernard K, Rizk N, Valensi P, Champault G. [Comparison of quality of life in morbidly obese patients and healthy volunteers. A prospective study using the GIQLI questionnaire]. J Chir (Paris). 2007;144:129-133; discussion 134. |

| 51. | Pizzi LT, Weston CM, Goldfarb NI, Moretti D, Cobb N, Howell JB, Infantolino A, Dimarino AJ, Cohen S. Impact of chronic conditions on quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:47-52. |

| 52. | Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Hass S, Niecko T, White J. Health-related quality of life during natalizumab maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2737-2746. |