Published online Jun 14, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i22.2828

Revised: April 16, 2010

Accepted: April 23, 2010

Published online: June 14, 2010

Periampullary cancer may cause not only biliary but also duodenal obstructions. In patients with concomitant duodenal obstructions, endoscopic biliary stenting remains technically difficult and may often require percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. We describe a method of metal stent placement via a thin forward-viewing endoscope in patients with simultaneous biliary and duodenal obstruction. In two consecutive patients with biliary and duodenal obstruction due to pancreatic cancer, a new biliary metal stent mounted in a slim delivery catheter was placed via a thin forward viewing endoscope after passage across the duodenal stenosis without balloon dilation. In both patients, with our new placement technique, metallic stents were successfully placed in a short time without adverse events. After biliary stenting, one patient received curative resection and the other received duodenal stenting for palliation. Metallic stent placement with a forward-viewing thin endoscope is a beneficial technique, which can avoid percutaneous drainage in patients with bilio-duodenal obstructions due to periampullary cancer.

- Citation: Maetani I, Nambu T, Omuta S, Ukita T, Shigoka H. Treating bilio-duodenal obstruction: Combining new endoscopic technique with 6 Fr stent introducer. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(22): 2828-2831

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i22/2828.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i22.2828

Patients with periampullary malignancies occasionally experience not only biliary but also duodenal obstructions. Although biliary obstruction usually occurs first and is followed by duodenal obstruction, the two occur simultaneously in some cases. These patients often require percutaneous biliary stenting because the endoscopic procedure is difficult.

A new commercially available self-expandable metallic stent (SEMS) mounted in an extra slim delivery catheter can be passed through the working channel of a thin endoscope. Here, we assessed the outcome of metal stent placement via a thin forward-viewing endoscope in two patients with simultaneous biliary and duodenal obstruction.

Two consecutive patients with simultaneous biliary and duodenal obstructions due to pancreatic cancer between November 2009 and January 2010 were investigated (Table 1). In both patients, duodenal obstructions did not allow the passage of a duodenoscope across the stricture without a dilating procedure. The patients underwent placement of SEMS via a slim forward-viewing gastroscope (GIF XP-240, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) (a valid length of 1030 mm, an outer diameter of 7.7 mm, a working channel diameter of 2.2 mm). The SEMS used is a new uncovered SEMS, Zilver® 635 stent (10 mm in diameter) (Cook, Bloomington, IN, USA) which is a laser-cut nitinol stent mounted in an extra slim (6-Fr) delivery catheter. The study was approved by our institutional review board (OHASHI #21-017), and written informed consent was obtained from the patients.

| Case | Age/sex | Level of duodenal obstruction | Level of biliary obstruction | Comorbidity | Purpose of biliary stenting | Subsequent procedures |

| 1 | 79/F | Pars II | Distal | None | Presurgical decompression | Pancreatico-duodenectomy |

| 2 | 81/M | Pars II | Distal | Advanced esophageal cancer | Palliation | Duodenal and esophageal stenting |

A slim endoscope was inserted perorally and passed across the stricture. The ampulla was endoscopically visualized by retroflexing the endoscope in the distal second portion of duodenum. An endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) catheter (PR-109Q, Olympus) was advanced into the bile duct using a wire-guided cannulation technique with a 0.025 “hydrophilic guidewire (Surf®, Piolax Medical Devices, Inc. Kanagawa, Japan). Then, the guidewire was replaced with a 0.035” Jagwire (Boston Scientific Inc., Natick, MA, USA), endoscopic papillary balloon dilation was performed with an 8-mm balloon dilator (Eliminator® PET biliary balloon dilator, ConMed, Utica, NY, USA), and the SEMS was released under endoscopic and fluoroscopic control.

A 79-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital due to obstructive jaundice. Computed tomography (CT) revealed pancreatic cancer with duodenal invasion. The patient underwent ERCP for biliary stenting, during which a duodenoscope (JF-260V, 12.6 mm outer diameter, Olympus) could not be passed across the stricture in the second portion of duodenum. Despite the presence of duodenal stricture, she was able to take soft food orally.

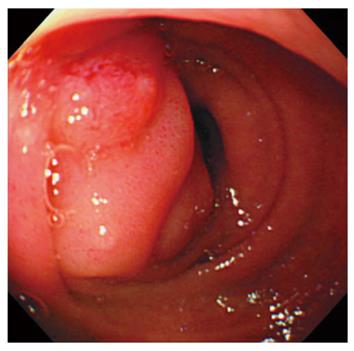

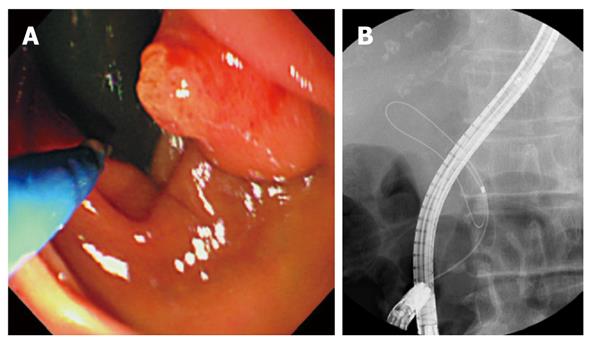

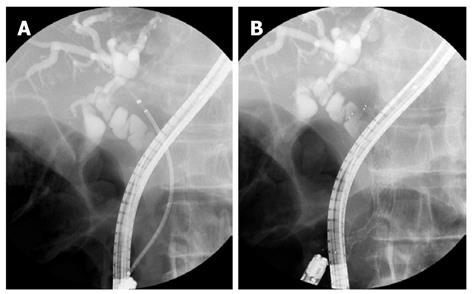

The new stenting procedure with a thin forward-viewing endoscope was employed. In brief, a slim endoscope was inserted perorally and easily passed across the stricture (Figure 1). After successful biliary cannulation (Figure 2), a Zilver® 635 stent (8 cm in length) was placed and deployed at the optimal position (Figure 3). The entire procedure took 35 min, and no complications were encountered.

After biliary stenting, her cancer was considered resectable based on the assessment with detailed examinations. The patient successfully underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy on day 14 after stenting when her jaundice was relieved. The resected specimen revealed duodenal invasion from pancreatic cancer. Since then, the patient has received adjuvant chemotherapy with S-1.

An 81-year-old man was admitted for epigastric pain, nausea and vomiting. Ultrasonography and CT revealed a 40-mm pancreatic mass with invasion to the extrahepatic bile duct, duodenum and portal vein. In addition, esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed an advanced cancer in the lower part of esophagus and a duodenal stenosis due to pancreatic cancer. The cancer was therefore considered unresectable. Because of these gastrointestinal obstructions, the patient could not take food orally and both biliary and duodenal stenting for palliation were scheduled. Liver function tests showed abnormal results, although jaundice was not identified. We carried out biliary stenting first in view of a treatment strategy based on scheduled palliative stenting, both biliary and duodenal[1].

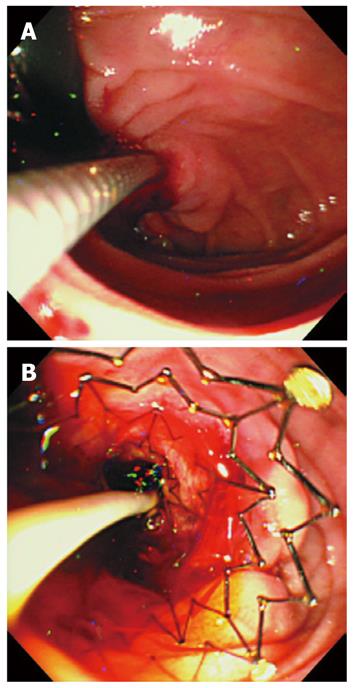

Because it was impossible to pass a large-caliber side-viewing duodenoscope (JF-260V, Olympus) through the duodenal stricture, we employed the new biliary stenting procedure with a thin forward-viewing endoscope as in Case 1 and subsequently placed a duodenal stent. A thin endoscope was easily passed across the duodenal as well as esophageal obstruction, after which a Zilver® 635 stent (8 cm in length) was successfully placed without difficulty, even through the endoscope was retroflexed as in Case 1 (Figure 4). The total procedure time was 22 min. No procedure-related complications were found.

On day 10 after biliary stent placement, the patient underwent stent placement at the duodenal stricture. A duodenal stent (Niti-S® Pyloric/Duodenal Uncovered Stent, Taewoong Medical Inc. Seoul, Korea) was successfully placed with a through-the-scope placement procedure at the optimal position. Two weeks after the duodenal stenting, the patient also underwent stent placement at the esophageal obstruction with an Ultraflex™ (Boston Scientific) (Figure 5). Biliary, duodenal and esophageal stenting improved his dietary status, allowing intake of solid food.

We report here the successful endoscopic placement of a biliary SEMS using a thin forward-viewing endoscope in two patients with simultaneous biliary and duodenal obstructions. One patient underwent the procedure for presurgical decompression and the other for palliation.

The combination of biliary and duodenal obstruction in patients with periampullary cancer is relatively frequent, as 23% of the patients had both biliary and duodenal obstructions in a retrospective study of unresectable pancreatic head cancer[2]. In most cases, duodenal obstruction occurs after biliary obstruction, but simultaneous obstruction also occasionally occurs. Because stent placement in these simultaneous cases is more complicated, these patients often require percutaneous biliary stenting. Even if a duodenoscope can be passed across the duodenal stricture when a duodenal stent is first placed, access to the ampulla may be hampered by stent mesh covering the papilla. Biliary stenting before duodenal stenting is therefore recommended for these patients[1]. However, because the stricture is usually too narrow to allow passage of a large-caliber duodenoscope, hydrostatic balloon dilation is frequently required[2,3]. Even after dilation, passage of a side-viewing duodenoscope across the obstruction is sometimes difficult, and is at a risk for duodenal perforation owing to the presence of acute angulation in the duodenum. Because the endoscope used in the present study is much thinner and forward-viewing, we were able to pass it easily and safely across the stricture under direct vision. The present technique thus has the great advantage of allowing the easier and safer emplacement of a biliary stent than a previously published technique of biliary stenting after a duodenal dilation with a side-viewing duodenoscope in patients with combined biliary and duodenal obstruction[2,3].

Although usually selected when endoscopic stenting is difficult, percutaneous stenting has two drawbacks, namely a compromised quality of life owing to the need for an indwelling percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) catheter for at least one week before stent placement, and the risk of cancer implantation in the catheter tract. A retrospective analysis of patients who underwent PTBD before resection of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma showed that catheter tract cancer-implantation develops in 6%[4]. Catheter tract cancer-implantation is reportedly observed in patients with pancreatic cancer as well as cholangiocarcinoma[5]. In recent years, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided biliary drainage has been introduced as an alternative to PTBD when ERCP is unsuccessful. However, this procedure is associated with procedure-specific complications, such as bile leak-attributable peritonitis[6,7], in addition to bleeding and cholangitis from stent dysfunction. Theoretically, it may cause cancer implantation in the peritoneal cavity and fistula track as in the case of PTBD. Transpapillary stenting is the only procedure conducted via a natural route and so must be the most desirable technique for presurgical as well as palliative decompression.

Recently, cholangiographic or cholangioscopic procedures with an ultra-slim endoscope have been reported[8,9]. A prospective comparison of transnasal ERCP with an ultrathin forward-viewing endoscope vs conventional ERCP with a large caliber side-viewing duodenoscope has reported no statistically significant difference in the rates or times of cannulation, albeit that the success rate of cannulation with the transnasal method is lower. The endoscope used in the present study (7.7 mm in diameter) is slightly larger than that used in the previous study (5.9 mm in diameter)[8]. Unlike the previous study, we introduced the endoscope into the duodenum perorally but were nevertheless able to accomplish biliary cannulation and stenting, without any difficulty. One previous case report of stent placement using an ultrathin forward-viewing endoscope per os has appeared[10], in which a patient with choledocholithiasis who received placement of two 5-Fr hand-made stents, subsequently underwent sphincterotomy and stone removal using a peroral ultrathin endoscope after relief of cholangitis. With plastic stents, thin endoscopes with a narrower working channel are restricted to accepting only 6 Fr or thinner stents. However, larger stents are generally more favorable than smaller ones, particularly for palliative use. We consider that the use of the new SEMS mounted in an extra slim delivery catheter takes full advantage of the possibilities of a thin endoscope with a thinner working channel.

When duodenal tumor invasion extends to the major papilla, endoscopic identification of the papilla is frequently difficult. Even if the papilla can be found, it is generally impossible to access the bile duct because of the difficulty of aligning the catheter with the bile duct axis. Under these conditions, therefore, stent placement would likely be difficult even with the present method and a percutaneous or EUS-guided transenteric procedure may be required instead. However, the number of such cases appears to be limited. The present report is a preliminary result with only two cases, and further study with more patients is warranted.

In conclusion, placement of the new SEMS mounted in an extra slim delivery catheter via a thin forward-viewing endoscope appears to be a safe and effective procedure for either presurgical or palliative decompression in patients with malignant biliary and duodenal obstruction. This study is preliminary, however, and further evaluation in a larger number of patients is warranted.

Peer reviewers: Yuk-Tong Lee, MD, Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, New Territories, Hong Kong, China; Hong Joo Kim, MD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Sungkyunkwan University Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, 108, Pyung-Dong, Jongro-Ku, Seoul, 110-746, South Korea

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Baron TH. Optimizing endoscopic placement of expandable stents throughout the GI tract. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;2:399-409. |

| 2. | Maire F, Hammel P, Ponsot P, Aubert A, O'Toole D, Hentic O, Levy P, Ruszniewski P. Long-term outcome of biliary and duodenal stents in palliative treatment of patients with unresectable adenocarcinoma of the head of pancreas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:735-742. |

| 3. | Kaw M, Singh S, Gagneja H. Clinical outcome of simultaneous self-expandable metal stents for palliation of malignant biliary and duodenal obstruction. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:457-461. |

| 4. | Sakata J, Shirai Y, Wakai T, Nomura T, Sakata E, Hatakeyama K. Catheter tract implantation metastases associated with percutaneous biliary drainage for extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:7024-7027. |

| 5. | Fiori E, Galati G, Bononi M, De Cesare A, Binda B, Ciardi A, Volpino P, Cangemi V, Izzo L. Subcutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer in the site of percutaneous biliary drainage. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2003;22:151-154. |

| 6. | Irisawa A, Hikichi T, Shibukawa G, Takagi T, Wakatsuki T, Takahashi Y, Imamura H, Sato A, Sato M, Ikeda T. Pancreatobiliary drainage using the EUS-FNA technique: EUS-BD and EUS-PD. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:598-604. |

| 7. | Püspök A. Biliary therapy: are we ready for EUS-guidance? Minerva Med. 2007;98:379-384. |

| 8. | Mori A, Ohashi N, Maruyama T, Tatebe H, Sakai K, Shibuya T, Inoue H, Takegoshi S, Okuno M. Transnasal endoscopic retrograde chalangiopancreatography using an ultrathin endoscope: a prospective comparison with a routine oral procedure. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1514-1520. |

| 9. | Larghi A, Waxman I. Endoscopic direct cholangioscopy by using an ultra-slim upper endoscope: a feasibility study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:853-857. |