Published online Jun 14, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i22.2818

Revised: April 1, 2010

Accepted: April 8, 2010

Published online: June 14, 2010

AIM: To explore the feasibility and therapeutic effect of total laparoscopic left hepatectomy (LLH) for hepatolithiasis.

METHODS: From June 2006 to October 2009, 61 consecutive patients with hepatolithiasis who met the inclusion criteria for LLH were treated in our institute. Of the 61 patients with hepatolithiasis, 28 underwent LLH (LLH group) and 33 underwent open left hepatectomy (OLH group). Clinical data including operation time, intraoperative blood loss, postoperative complication rate, postoperative hospital stay time, stone clearance and recurrence rate were retrospectively analyzed and compared between the two groups.

RESULTS: LLH was successfully performed in 28 patients. The operation time of LLH group was longer than that of OLH group (158 ± 43 min vs 132 ± 39 min, P < 0.05) and the hospital stay time of LLH group was shorter than that of OLH group (6.8 ± 2.8 d vs 10.2 ± 3.4 d, P < 0.01). No difference was found in intraoperative blood loss (180 ± 56 mL vs 184 ± 50 mL), postoperative complication rate (14.2% vs 15.2%), and stone residual rate (intermediate rate 17.9% vs 12.1% and final rate 0% vs 0%) between the two groups. No perioperative death occurred in either group. Fifty-seven patients (93.4%) were followed up for 2-40 mo (mean 17 mo), including 27 in LLH group and 30 in OLH group. Stone recurrence occurred in 1 patient of each group.

CONCLUSION: LLH for hepatolithiasis is feasible and safe in selected patients with an equal therapeutic effect to that of traditional open hepatectomy.

-

Citation: Tu JF, Jiang FZ, Zhu HL, Hu RY, Zhang WJ, Zhou ZX. Laparoscopic

vs open left hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(22): 2818-2823 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i22/2818.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i22.2818

Hepatolithiasis refers to the stone in branching bile ducts above the confluence of left and right hepatic ducts. It may occur alone or with extrahepatic bile duct stones and is a prevalent disease in Southeast Asia and its incidence is also higher in Chinese coast areas, southwest region, Hong Kong and Taiwan. Hepatectomy is a definite and effective approach for hepatolithiasis[1,2]. With the refinement of laparoscopic instruments and accumulated experience in both laparoscopic surgery and hepatic surgery, laparoscopic hepatectomy has been used in treatment of hepatic benign and malignant tumors and donor hepatectomy of live donor liver transplantation[3,4]. However, few studies are available on laparoscopic hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis[5-8]. We successfully used total laparoscopic left hepatectomy (LLH) to treat hepatolithiasis in 8 patients between November 2003 and May 2006, and have preliminarily accumulated surgical experience with it and considered this operation safe and feasible[9]. To further explore the therapeutic effect of total LLH on hepatolithiasis, clinical data about 61 consecutive patients with hepatolithiasis who underwent LLH or open left hepatectomy (OLH) were retrospectively analyzed and compared.

The inclusion criteria for LLH for hepatolithiasis include (1) multiple stones in the left or left lateral intrahepatic ducts with fibrosis and atrophy of hepatic lobes or hepatic segments; (2) possibly combined with extrahepatic bile duct stones or a few stones in the right intrahepatic ducts, but with no extrahepatic bile duct stricture or stone incarceration in the lower part of common bile duct; and (3) liver function of Child A to B classification, with no portal hypertension, coagulation disorder, structural disease in the heart, lungs, liver and kidneys, intrahepatic biliary cancer, and abdominal surgical histories.

From June 2006 to October 2009, 61 consecutive patients with hepatolithiasis who met the inclusion criteria for LLH were treated in our institute. Of the 61 patients with hepatolithiasis, 28 underwent LLH (LLH group) and 33 underwent OLH (OLH group). Before operation, all patients had a complete medical evaluation, including liver function, renal function, electrocardiogram and chest X-ray. Preoperative ultrasonography, CT and MRCP were performed to identify the distribution of stones and changes in the bile duct tree. Of the 28 patients in LLH group, 10 were men and 18 women, with a mean age of 47 years (range 25-63 years). Twenty-one patients had left hepatolithiasis and 7 left and right hepatolithiasis. Twelve patients were accompanied with cholecystolithiasis, 13 with choledocholith, and 6 with mild jaundice. Liver function was classified as Child A and B in 22 and 6 patients, respectively. Two patients had a history of biliary surgery. Of the 33 patients in OLH group, 12 were men and 21 women with a mean age of 49 years (range 31-68 years). Twenty-three patients had left hepatolithiasis and 10 left and right hepatolithiasis. Twelve patients were accompanied with cholecystolithiasis, 15 with choledocholithiasis, and 9 with mild jaundice. Liver function was classified as Child A and B in 25 and 8 patients, respectively. Three patients had a history of biliary surgery. No significant difference was found in age, sex, stone distribution, liver function and surgical history between the two groups.

Patients in LLH group, placed in supine position, underwent general anesthesia. The chief surgeon stood on the left of the patient and the first assistant on the right. Another surgeon who supported the mirror stood on the left of the chief surgeon. Two monitors were placed above each side of the patient’s head. A 10-mm cut was made below the umbilicus and a CO2 pneumoperitoneum was established at a pressure of 14 mmHg. A 30° angled laparoscope was introduced. Under direct vision, two 12-mm trocars were respectively inserted below the xiphoid bone and the costal margin of the left mid-clavicular line, and a 5-mm trocar was also inserted below the costal margin of the right mid-clavicular line.

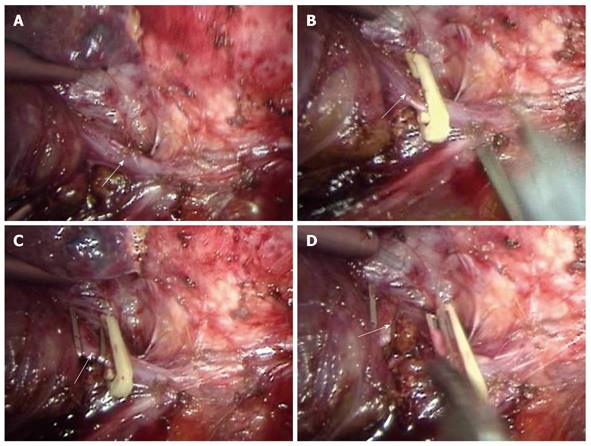

Left lateral segmentectomy: Laparoscopy was performed with the round and falciform ligaments transected using an ultrasound knife (Johnson & Johnson, USA). By meticulous dissection, the artery and vein of left lateral segment were visualized, clamped with absorbable clips and divided. Interrupted bile ducts were not clamped temporarily. Left triangular and coronary ligaments were divided with the trunk or branch of the left hepatic vein carefully dissected properly away from the second hepatic portal. If the confluence point of left hepatic veins and inferior vena cava was very close to the posterior border of the left liver, the left hepatic veins were clamped extremely near the posterior border of the left liver, but not divided until complete removal of Couinaud. If the confluence point of left hepatic veins and inferior vena cava was away from the liver parenchyma, the left hepatic vein was dissected, clamped with absorbable clips and divided (Figure 1). Liver parenchyma was transected from left of the round ligament to liver inferior border of sagittal portion, vessels and bile ducts in the transection plane were bluntly dissected, clamped and divided. Dilated intrahepatic bile ducts in the transection plane were opened. According to the size, number and position of residual stones, stone forceps were introduced below the xiphoid bone to directly remove stones, or a fiber choledochoscope (Olympus, Japan) was used to remove stones from the transection plane. If the stones were near the distal common bile duct or bigger, or combined with right hepatolithiasis, common bile duct exploration was performed to remove the stones. Cholecystectomy was done routinely. Continuous or interrupted suture was performed for the transection plane with 3-0 Vicryl. Water was injected via a T tube to determine whether the suture was tight. The transection plane was coagulated with fibrin glue to seal capillary vessels or covered with absorbable hemostatic gauze. The integral specimen was packed into a plastic bag and removed via an extended trocar hole. A drainage tube was left in vicinity of the transection plane through the costal margin of the left mid-clavicular line. Whether a drainage tube is left near the first hepatic portal depends on the intraoperative conditions.

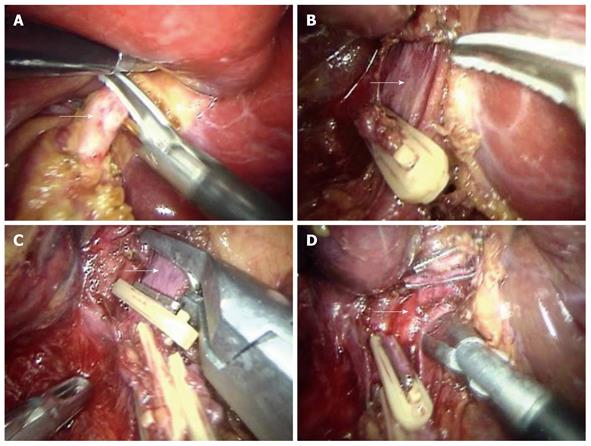

Left hemihepatectomy: In the first hepatic portal, the left hepatic artery and the left branch of portal vein were dissected. The proximal end of left hepatic artery was clamped with two absorbable clips, the left hepatic artery was clamped with a mental soft clip 2-3 mm away from the absorbable clips, and the left hepatic artery was divided between mental and absorbable clips. The left branch of portal vein was treated with the same method (Figure 2). Other surgical procedures were the same as those in left lateral segmentectomy.

In OLH group, an oblique incision was made along the right costal margin or along the right rectus abdominis with the patients in supine position under general anesthesia. Cholecystectomy was done routinely. Common bile duct exploration was performed to remove stones. Couinaud was removed with a T drainage tube left.

Residual stones were completely removed by fiber choledochoscopy via the T tube sinus tract after operation in both groups.

Clinical data including operation time, intraoperative blood loss, postoperative complication rate, postoperative hospital stay time, and stone clearance and recurrence rate were compared between the two groups. Follow-up data were obtained from hospital charts or by telephone.

Categorical parameters of each group were compared by χ2 test, and continuous parameters were compared using independent-sample t test. All analyses were performed using SPSS 12.0. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Laparoscopic left hepatectomy was successfully performed in 28 patients. Of the 28 patients, 3 underwent laparoscopic left hemihepatectomy, cholecystectomy, common bile duct exploration and T tube drainage, 18 underwent left lateral segmentectomy, cholecystectomy and common bile duct exploration. Of the 18 patients, 6 underwent primary suture of common bile duct, 12 underwent T tube drainage, 5 underwent left lateral segmentectomy with cholecystectomy, 1 underwent left lateral segmentectomy, common bile duct exploration and T tube drainage, and 1 underwent left lateral segmentectomy. All the 28 patients in LLH group underwent intraoperative cholangioscopic bile duct exploration or stone removal. Of the 33 patients in OLH group, 5 underwent open left hemihepatectomy, cholecystectomy, common bile duct exploration and T tube drainage, 23 underwent left lateral segmentectomy, cholecystectomy and common bile duct exploration. Of the 23 patients, 4 underwent primary suture of common bile duct, 19 underwent T tube drainage. Twenty-eight patients in OLH group underwent cholangioscopic bile duct exploration with stones removed (Table 1). Intraoperative findings and postoperative pathology displayed hepatolithiasis, cholangiectasis of Couinaud, chronic inflammation and fibration in all patients.

| Variables | LLH (n = 28) | OLH (n = 33) |

| Left hemihepatectomy | 3 | 5 |

| Left lateral segmentectomy | 25 | 28 |

| Combined with cholecystectomy | 26 | 30 |

| Combined with CBD exploration | 22 | 31 |

| T tube drainage | 16 | 27 |

| Primary suture of CBD | 6 | 4 |

| Intraoperative choledochoscope | 28 | 28 |

The mean operation time was longer in LLH group than in OLH group (158 ± 43 min vs 132 ± 39 min, P < 0.05). The intraoperative blood loss in two groups was similar (180 ± 56 mL vs 184 ± 50 mL). One patient in OLH group was transfused with 2 units of concentrated red blood cells, no patient in LLH group received blood transfusion. Bile leakage occurred in 2 patients of LLH group, and healed automatically 3 and 5 d after operation. Pleural effusion, observed in 2 patients, disappeared after thoracentesis. In OLH group, seroperitoneum occurred in 1 patient, hepatic abscess in 1 patient and infection of incision in 3 patients. No significant difference was found in complication rate (14.2% vs 15.2%) and intermediate stone residual rate (17.9% vs 12.1%) between the two groups. The mean postoperative hospital stay time was shorter in LLH group than in OLH group (6.8 ± 2.8 d vs 10.2 ± 3.4 d, P < 0.01), and the serum transaminase was transiently increased and jaundice disappeared at discharge with no death occurred in both groups (Table 2).

| Variables | LLH (n = 28) | OLH (n = 33) |

| Operating time (min) | 158 ± 43 | 132 ± 39 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 180 ± 56 | 184 ± 50 |

| Intraoperative blood transfusion | 0 (0) | 1 (3.0) |

| Postoperative complications | 4 (14.2) | 5 (15.2) |

| Postoperative hospital stay (d) | 6.8 ± 2.8 | 10.2 ± 3.4 |

| Intermediate residual stone | 5 (17.9) | 4 (12.1) |

| Final residual stone | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Stone recurrence | 1 (3.6) | 1 (3.0) |

| Perioperative mortality | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Of the 16 patients in LLH group discharged with their T tubes, 11 underwent T extubation 28-35 d after operation, 5 underwent it 42-60 d after operation when residual stones were completely removed by choledochoscopy. Of the 27 patients in OLH group discharged with their T tubes, 23 underwent T extubation 28-40 d after operation, 4 underwent it 50-60 d after operation when residual stones were completely removed by choledochoscopy. Fifty-seven patients (93.4%) including 27 in LLH group and 30 in OLH group were followed up for 2-40 mo (mean 17 mo). Stone recurrence was found in 1 patient of LLH group and in 1 patient of OLH group. Intrahepatic biliary cancer occurred in 1 patient of OLH group 29 mo after operation, and was surgically removed in another hospital.

In 1991, Reich et al[10] used laparoscope to remove a benign tumor located at the edge of liver, raising the curtain on laparoscopic hepatectomy. In 1993, Wayand et al[11] performed laparoscopic segmentectomy (segments VI) for metastatic carcinoma. In 1996, Azagra et al[12] first performed laparoscopic left lateral lobectomy (segments II and III) for hepatic adenoma in 1 patient. With the refinement of laparoscopic instruments and accumulated experience in laparoscopic hepatectomy, indications for laparoscopic hepatectomy have gradually expanded from small, peripheral and benign diseases to large, central and malignant diseases[13,14]. Lesions located in Couinaud including II, III, IVa, V and VI segments are the best indications for laparoscopic hepatectomy, and regular left lateral lobectomy is expected to become its gold standard[8,15]. Most intrahepatic bile duct stones, especially left intrahepatic bile duct stones, manifested as a regional distribution, are usually combined with liver fibrosis and atrophy, which is also a good indication for laparoscopic hepatectomy[8,16]. The inclusion criteria for LLH for hepatolithiasis in this study were (1) multiple stones in the left or left lateral intrahepatic ducts with fibrosis and atrophy of hepatic lobes or segments, possibly combined with extrahepatic bile duct stones or a few stones in the right intrahepatic ducts; and (2) except for lots of stones in the right intrahepatic ducts, severe acute cholangitis, hepatic abscess, stone incarceration in the lower part of common bile duct and bile duct neoplasms. We believe that only LLH rather than common bile duct exploration is required for simple left hepatolithiasis. Chen et al[16] has described that endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) for left hepatolithiasis with extrahepatic bile duct stones, can completely remove common bile duct stones followed by laparoscopic hepatectomy. However, ERCP easily causes acute pancreatitis, thus making cholelithiasis heavier and EST destroys the integrity of duodenal papilla and sphincter Oddi, easily leading to biliary tract infection and difficulty to remove the stones with a diameter > 1.5 cm. Preoperative hospital stay time is significantly increased and secondary operation is required. In this study, common bile duct exploration was performed to remove stones followed by T-tube drainage or primary suture of common bile duct, which is suitable for different sizes of common bile duct stones, but is time-consuming and may lead to bile leakage. External drainage of bile may lead to electrolytical and digestive unbalance, which is not beneficial to postoperative recovery. Choledochoscopy can remove the stones through the stump of the left hepatic duct without cutting open the common bile duct, thus avoiding the above disadvantages. However, it is only suitable for a small number of patients. In this study, a few stones in the right hepatic bile duct were removed by intraoperative choledochoscopy through the common bile duct or by postoperative choledochoscopy via the T-tube sinus tract.

The liver possesses dual blood supply from hepatic artery and portal vein. Blood supply is abundant and bleeding easily occurs. During laparoscopic hepatectomy, since hepatic portal occlusion, hand pressure and saturation cannot be used for hemostasis, it is not easy to control intraoperative bleeding[17]. Therefore, how to prevent, control and reduce intraoperative bleeding is a key to surgical success and postoperative recovery[18]. In our study, full preoperative preparation was done for each patient. The patients with normal liver function and coagulation test were selected. Preoperative ultrasonography, CT or MRCP was performed to determine the distribution, location and size of stones and liver morphology. The stones were located in Couinauds II and III. The operators had rich experience in traditional hepatectomy and skilled laparoscopic technique. Excellent surgical instruments such as ultrasonic bleeding knife, vascular closure device and Ligasure vessel sealing system were provided. Each segment of the left liver was dissected in the first hepatic portal, and blocked with clips. The portal vascular structure of left liver was dissected outside Glisson sheath, and the branches of portal vein and hepatic artery were clamped with absorbable clips. The left hepatic vein trunk was dissected, clamped with clips and divided after transection of liver parenchyma. The transaction of liver parenchyma resulted in less tissue damage, less bleeding and good exposure of hepatic duct system. It was reported that Peng’s multifunctional operative dissector can reduce bleeding and operation time[19]. The ideal level of regular left lateral lobectomy is at the sagittal plane 1 cm away from the left of falciform ligament. The main vessels at this plane include superior and inferior segment branch of Couinaud of portal vein, trunk of left hepatic vein, left and upper branches of left hepatic vein, which are distributed in 2/3 of the superior part. Choledochoscope can enter the common bile duct or the right hepatic duct through the broken end of left hepatic duct or incisional anterior wall of the common bile duct to remove stones[6,7]. If no biliary tract stricture is identified, small stones may not be completely removed, and then a T tube is left. The residual small stones can be removed by choledochoscopy 6 wk after operation.

Hepatolithiasis is common in China, accounting for about 10% of calculosis, or 40%-50% in some areas. Stone clearance rate for open hepatectomy can reach 81.7% with a reliable long-term therapeutic effect[20]. Laparoscopic hepatectomy can achieve the same stone clearance rate in the left liver[6]. Zhang et al[8] reported that the therapeutic effect of laparoscopic left lateral lobotomy for left hepatolithiasis and choledocholith is better than that of traditional open stone removal. Machado et al[21] reported one patient who underwent laparoscopic right hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis, showing that the learning curve can influence the feasibility and repeatability of laparoscopic hepatectomy[22]. In this study, the therapeutic effects of laparoscopic and open hepatectomy on intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct stones were compared as previously described[9]. Although randomized controlled trial data are lack, the blood loss, blood transfusion rate, complication rate and mortality in laparoscopic hepatectomy were equal to those in open hepatectomy. It was reported that the evacuating time, fasting time, use of analgesics, hospital stay time, time to return to work and degree of satisfaction are better in laparoscopic hepatectomy than in open hepatectomy, while operation time is longer and cost is higher in laparoscopic hepatectomy than in open hepatectomy[5,23,24]. In our study, the mean operation time of LLH group was longer than that of OLH group, the mean blood loss and postoperative complication rate were similar in the two groups, the mean hospital stay time was significantly shorter in LLH group (6.8 ± 2.8 d) than in OLH group (10.2 ± 3.4 d) possibly due to the mini-invasive advantages, such as small incision, postoperative light inflammatory response, less interference with immune function. In addition, intermediate and final stone clearance rate and long term stone recurrence rate for the two groups were also similar with no CO2 gas embolism occurred in patients of LLH group. Air embolism is a potential risk factor for laparoscopic hepatectomy.

In summary, LLH for hepatolithiasis is safe and feasible in selected patients if it is performed by surgeons with experience in laparoscopic and hepatic surgery. Its therapeutic effect is equal to that of traditional open hepatectomy. Laparoscopic hepatectomy has the advantages such as mini-invasion, less postoperative pain and rapid recovery.

Hepatolithiasis is a prevalent disease in Southeast Asia with a high incidence in coast areas, southwest region, Hong Kong and Taiwan of China. Hepatectomy is a definite and effective procedure for hepatolithiasis. With the refinement of laparoscopic instruments and accumulated experience in laparoscopic and hepatic surgery, laparoscopic hepatectomy has been used in treatment of hepatic benign and malignant tumors and donor hepatectomy for live donor liver transplantation. However, few studies are available on on laparoscopic hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis.

The feasibility and therapeutic effect of total laparoscopic left hepatectomy (LLH) on hepatolithiasis are a hotspot.

This study explored the therapeutic effect of laparoscopic vs open left hepatectomy on hepatolithiasis and concluded that LLH for hepatolithiasis is feasible and safe in selected patients if it is performed by experienced surgeons. Its therapeutic effect is equal to that of traditional open hepatectomy.

Laparoscopic hepatectomy possesses the advantages such as mini-invasion, less postoperative pain and rapid recovery and worth of spreading.

Hepatolithiasis: It refers to stones in the branching bile ducts above the confluence of left and right hepatic ducts, and may occur alone or in combination with extrahepatic bile duct stones.

It is interesting and well-written. The results show that laparoscopic hepatectomy is worth of spreading due to its advantages such as mini-invasion, less postoperative pain and rapid recovery.

Peer reviewer: Giuseppe Currò, MD, University of Messina, Via Panoramica, 30/A, 98168 Messina, Italy

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Uenishi T, Hamba H, Takemura S, Oba K, Ogawa M, Yamamoto T, Tanaka S, Kubo S. Outcomes of hepatic resection for hepatolithiasis. Am J Surg. 2009;198:199-202. |

| 2. | Lee TY, Chen YL, Chang HC, Chan CP, Kuo SJ. Outcomes of hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis. World J Surg. 2007;31:479-482. |

| 3. | Zhang L, Chen YJ, Shang CZ, Zhang HW, Huang ZJ. Total laparoscopic liver resection in 78 patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5727-5731. |

| 4. | Nguyen KT, Gamblin TC, Geller DA. World review of laparoscopic liver resection-2,804 patients. Ann Surg. 2009;250:831-841. |

| 5. | Lai EC, Ngai TC, Yang GP, Li MK. Laparoscopic approach of surgical treatment for primary hepatolithiasis: a cohort study. Am J Surg. 2010;199:716-721. |

| 6. | Cai X, Wang Y, Yu H, Liang X, Peng S. Laparoscopic hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis: a feasibility and safety study in 29 patients. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1074-1078. |

| 7. | Di Giuro G, Balzarotti R, Lainas P, Franco D, Dagher I. Laparoscopic left hepatectomy with intraoperative biliary exploration for hepatolithiasis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1147-1148. |

| 8. | Zhang K, Zhang SG, Jiang Y, Gao PF, Xie HY, Xie ZH. Laparoscopic hepatic left lateral lobectomy combined with fiber choledochoscopic exploration of the common bile duct and traditional open operation. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1133-1136. |

| 9. | Jiang FZ, Tu JF, You HY, Han Y, Zheng XF, Zhang QY. [Laparoscopic left hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis]. Gandanyi Waike Zazhi. 2007;19:103-104. |

| 10. | Reich H, McGlynn F, DeCaprio J, Budin R. Laparoscopic excision of benign liver lesions. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78:956-958. |

| 11. | Wayand W, Woisetschläger R. [Laparoscopic resection of liver metastasis]. Chirurg. 1993;64:195-197. |

| 12. | Azagra JS, Goergen M, Gilbart E, Jacobs D. Laparoscopic anatomical (hepatic) left lateral segmentectomy-technical aspects. Surg Endosc. 1996;10:758-761. |

| 13. | Laurence JM, Lam VW, Langcake ME, Hollands MJ, Crawford MD, Pleass HC. Laparoscopic hepatectomy, a systematic review. ANZ J Surg. 2007;77:948-953. |

| 14. | Tranchart H, Di Giuro G, Lainas P, Roudie J, Agostini H, Franco D, Dagher I. Laparoscopic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: a matched-pair comparative study. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1170-1176. |

| 15. | McPhail MJ, Scibelli T, Abdelaziz M, Titi A, Pearce NW, Abu Hilal M. Laparoscopic versus open left lateral hepatectomy. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;3:345-351. |

| 16. | Chen P, Bie P, Liu J, Dong J. Laparoscopic left hemihepatectomy for hepatolithiasis. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:717-718. |

| 17. | Vibert E, Perniceni T, Levard H, Denet C, Shahri NK, Gayet B. Laparoscopic liver resection. Br J Surg. 2006;93:67-72. |

| 18. | Di Giuro G, Lainas P, Franco D, Dagher I. Laparoscopic left hepatectomy with prior vascular control. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:697-699. |

| 19. | Peng SY, Li JT, Mou YP, Liu YB, Wu YL, Fang HQ, Cao LP, Chen L, Cai XJ, Peng CH. Different approaches to caudate lobectomy with "curettage and aspiration" technique using a special instrument PMOD: a report of 76 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2169-2173. |

| 20. | Yang T, Lau WY, Lai EC, Yang LQ, Zhang J, Yang GS, Lu JH, Wu MC. Hepatectomy for bilateral primary hepatolithiasis: a cohort study. Ann Surg. 2010;251:84-90. |

| 21. | Machado MA, Makdissi FF, Surjan RC, Teixeira AR, Sepúlveda A Jr, Bacchella T, Machado MC. Laparoscopic right hemihepatectomy for hepatolithiasis. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:245. |

| 22. | Vigano L, Laurent A, Tayar C, Tomatis M, Ponti A, Cherqui D. The learning curve in laparoscopic liver resection: improved feasibility and reproducibility. Ann Surg. 2009;250:772-782. |

| 23. | Kazaryan AM, Pavlik Marangos I, Rosseland AR, Røsok BI, Mala T, Villanger O, Mathisen O, Giercksky KE, Edwin B. Laparoscopic liver resection for malignant and benign lesions: ten-year Norwegian single-center experience. Arch Surg. 2010;145:34-40. |

| 24. | Ito K, Ito H, Are C, Allen PJ, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, Jarnagin WR, D'Angelica MI. Laparoscopic versus open liver resection: a matched-pair case control study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:2276-2283. |