Published online Jun 7, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i21.2677

Revised: February 10, 2010

Accepted: February 17, 2010

Published online: June 7, 2010

AIM: To analyze the clinical and imaging features of the small intestinal lipomas and to evaluate the diagnostic value of multi-slice computed tomography (CT) enterography.

METHODS: Fourteen cases (one had two intestinal lesions) of surgically confirmed lipomas of the small intestine were retrospectively analyzed. The location, size, clinical and radiological aspects were discussed.

RESULTS: Twelve patients presented with abdominal pain, of whom three complained of paroxysmal colic. Melena or bloody stools was mentioned in five cases. One lesion was detected incidentally during routine physical examination. One lesion was found unexpectedly during the preoperational evaluation for cholecystitis. Examination of the abdomen revealed palpable masses in four cases. Precontrast CT scan showed round or oval well-defined hypo-intense intraluminal masses with the attenuation ranging from -130 HU to -60 HU. On contrast enhancement CT scan, no striking enhancement was seen.

CONCLUSION: The small intestinal lipomas are rare and difficult to diagnose merely based on clinical manifestations, while the characteristic features at small intestinal CT enterography can help establish reliable prospective diagnoses.

- Citation: Fang SH, Dong DJ, Chen FH, Jin M, Zhong BS. Small intestinal lipomas: Diagnostic value of multi-slice CT enterography. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(21): 2677-2681

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i21/2677.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i21.2677

Primary small intestinal tumors are uncommon, which account for about 1% of all gastrointestinal tumors, and primary lipomas of the small intestine are rare[1-5]. Preoperative diagnosis is usually indeterminate only based on clinical manifestations due to the overlap of symptoms and signs with other intestinal tumors. Benign tumors in the small intestine do not have a characteristic computed tomography (CT) appearance and, in most instances, cannot be differentiated from malignant lesions, but lipomas can be definitively diagnosed by the recognition of fat attenuation within the mass[1]. To the best of our knowledge, only case reports of small bowel lipoma were presented in the literature[1-4]. Herein we present 15 surgically confirmed small intestinal lipomas and analyze retrospectively their clinical, pathological and imaging findings, especially multi-slice CT enterography.

The institutional review board approved this retrospective study and waived the need to obtain patient consent. Fourteen patients (one had two intestinal lesions) treated at three hospitals (Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital; First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine and Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital, China) from May 1994 to June 2009 were enrolled. All patients (four women and ten men; age range, 19-82 years; mean age, 63.2 years) with pathologically confirmed lipoma underwent 16-detector row CT enterography before surgery.

Melena or bloody stools was mentioned in five cases. Fecal occult blood test was positive in nine cases and negative in the other five cases. No significant abnormality was found in blood biochemical tests. Twelve patients presented with abdominal pain, three of them complained of paroxysmal colic and were subsequently found to have intestinal obstruction secondary to intussusception. They denied vomiting, fever, or chills. One lesion was detected incidentally during routine physical examination. One lesion was found unexpectedly during the preoperational investigation for cholecystitis. Physical examination of the abdomen revealed palpable masses in four cases.

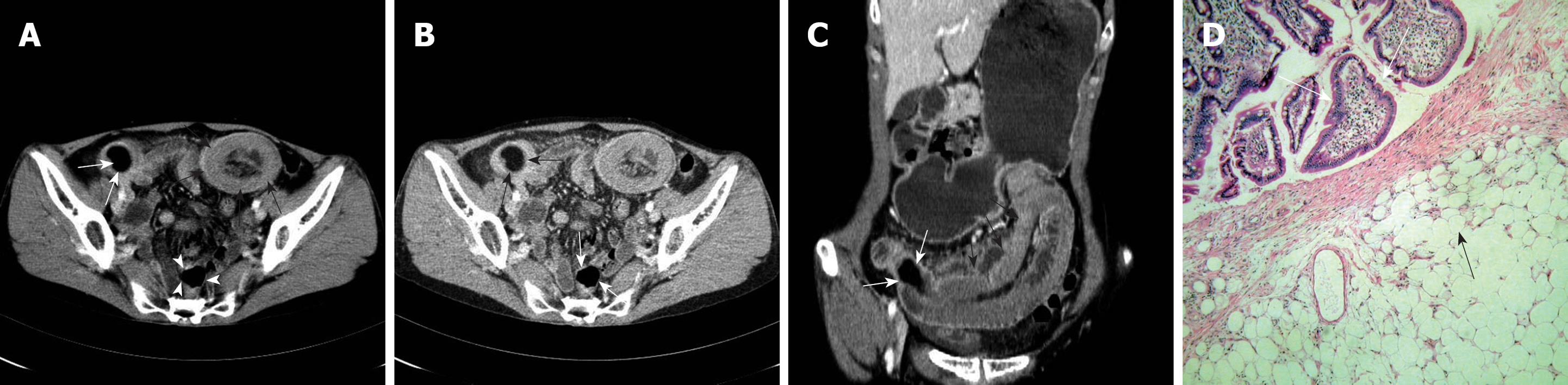

Fourteen patients had confirmed small intestinal lipomas (Figures 1, 2, 3), including one who had two intestinal lesions. Four of the 15 tumors occurred in the duodenum, three in the jejunum, and eight in the ileum (Figures 1, 2, 3).

The size of the lesions ranged from 2 cm × 1.5 cm × 1.1 cm to 6.3 cm × 4.5 cm × 2 cm (mean, 3.9 cm × 2.8 cm × 2.3 cm). The tumors were round or oval (Figures 1, 2, 3) and three were pedunculated in shape.

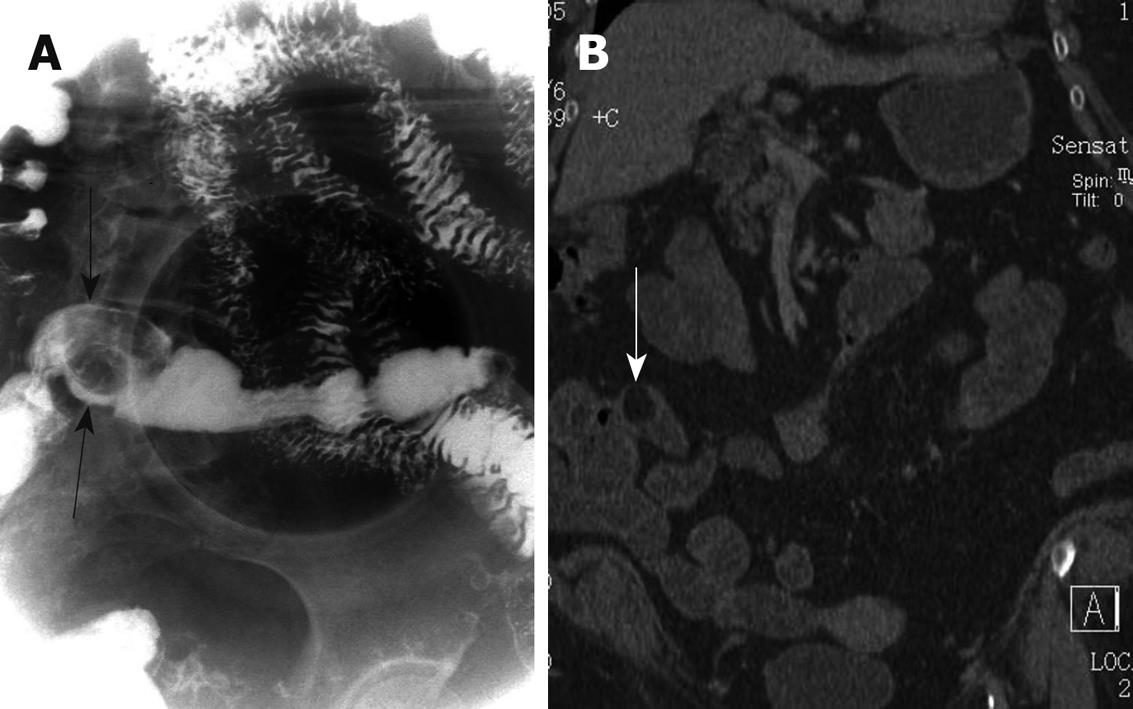

Precontrast CT scan showed round or oval well-circumscribed hypo-intense intraluminal masses with the attenuation ranging from -130 HU to -60 HU (Figure 2). Eleven of the 15 tumors were homogeneous, while the remaining four were heterogeneous with several streak septa. No enhancement after intravenous contrast material administration (Figures 1, 2, 3) was found in all the lesions, except the streak septa which was enhanced minimally. Small intestinal CT enterography demonstrated the typical “target” appearance (Figure 1) as intestinal intussusception in three cases. Except one of the three patients with intussusception, all other 13 patients had a definitive preoperative diagnosis of lipomas by the CT enterography, which were confirmed by subsequent surgical pathology.

At laparotomy, a jejunojejunal or ileoileac intussusception (Figures 1 and 3) was present in three cases. One patient had two separated submucosal lipomas. All tumors were defined to originate from the submucosal layer. Grossly they had a clear margin and yellow section surface. Microscopically (Figure 1D), they were composed of mature adipose cells, nine tumors had overlying necrosis and ulceration, and four showed inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia with septa formation extending in the adipose tissue.

Tumors of small intestine account for only 1%-2% of all gastrointestinal tumors, and benign tumors account for approximately 30% of all small intestinal tumors[6]. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors are the most common symptomatic benign tumors of the small bowel, while the lipomas are rare benign tumors, representing 2.6% of non-malignant tumors of the intestinal tract[2].

Lipomas are often single submucosal intraluminal masses, with intensely yellow color in the mucosa because of the underlying accumulated fat. They usually appear as a capsulated round or oval yellowish mass protruding into the intestinal lumen. Sometimes there is overlying ulceration of the mucosa[7-10].

Small bowel lipomas tend to occur in the elderly, and the sixth to seventh decades of life are considered to be the most risky period[3,11,12]. Jejunum and ileum, especially the terminal ileum, are common locations. Eleven of the 15 lesions arose from jejunoileum and the mean age of the patients was 63.2 years in this study, which was consistent with those previously reported. Patients may be completely asymptomatic with small lipomas (< 1 cm), which are usually detected incidentally. Larger tumors may produce symptoms as follows.

Paroxysmal abdominal pain: About 75% patients present with abdominal pain in different degree. Twelve of the 14 patients in this study complained of abdominal pain and 3 suffered from severe colic due to intussusception. Tumor traction, peristalsis disorder, intestinal obstruction, tumor necrosis or secondary infection may result in abdominal pain while the intestinal obstruction due to lipomas is usually characterized clinically by recurrent severe abdominal pain with increased bowel sound and locally palpable round or oval masses. Lesions greater than 4cm in diameter have a greater likelihood of introducing bowel intussusception, and submucosal or subserosal lipomas also tend to cause intussusception[7,13-15]. Large subserosal tumors are prone to result in intestinal compression and volvulus.

Hemorrhage of digestive tract: Approximately 25% of patients with benign intestinal neoplasm have alimentary tract hemorrhage. Small bowel lipomas usually cause lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage, and lipomas arising from duodenum may cause upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage and symptoms like peptic ulcer. Some of the bleeding is intermittent, some is continuous in small amount or only presents as microscopically positive fecal occult blood. Melena or bloody stools was mentioned in five cases and fecal occult blood test was positive in nine cases in this study.

Abdominal masses: Large lipomas may be palpable as soft, lobulated and movable abdominal masses without tenderness. Of the 4 patients who had palpable masses in this study, three were ill-defined with tenderness, possibly due to the intestinal intussusception.

Other reported clinical symptoms include nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea and abdominal distention. Pedunculated submucosal lipomas may ablate spontaneously and discharged from anus when there are volvulus and necrosis.

Preoperative diagnosis of the small intestinal lipomas is mainly established by means of endoscopic and radiologic evaluations. The duodenal lipomas are endoscopically characterized by: (1) “tenting sign”, implying that the mucosa can be pulled from the lesion with biopsy forceps on endoscopy; and (2) “cushion sign”, implying spongy consistency of the lesion when indented with biopsy forceps and yellowish change of the mucosa from normal pink appearance for the compression of the vessels, representing the underlying lipoma[16].

The diagnosis of the jejunoileal lipomas mainly depends on the imaging modalities as follows.

The role of abdominal conventional radiographs for the evaluation of lipomas is limited. Mechanic intestinal obstruction or low density of the lipid is occasionally seen[17]. Abdominal X-ray films of two patients in our series revealed small bowel obstruction but failed to suggest the primary disease.

Double-contrast barium study, especially small bowel enema, may be helpful for the lipomas evaluation. The tumor commonly presents as round, oval or lobulated well-circumscribed intraluminal filling defect (Figure 2A), with so-called “squeeze sign” in which the shape of the mass changes as a consequence of peristalsis or manual pressure[3]. Some pedunculated tumors are movable and may change their locations in response to position or palpitation. There is also so-called “bull’s-eye sign” signifying a niche formation in the radiolucent filling defect due to ulceration. The intestinal peristalsis remains normal and the mucosa is intact. However, barium study still has limitations in many aspects including: (1) overlap of the intestinal loops, which makes unsatisfactory display and may result in misdiagnosis; (2) difficult differentiation from other tumors which also present as filling defects; (3) disability to detect small lipomas; and (4) contraindication in patients accompanying intestinal obstruction or intussusception.

Ultrasound may detect large lipomas of the small intestine as hyper- or hypo-echoic masses, or irregular sausage-shaped masses, of which the inner central part is hyper-echoic and the peripheral area is hypo-echoic representing intestinal intussusception[15,17]. However, the role of ultrasound is also limited greatly because of the noise interference caused by the intraluminal gas. Ultrasound examination of the two cases of our series both failed to establish a correct diagnosis.

Abdominal CT scans are considered to be the most definitive diagnostic measure of recognizing small bowel lipomas[1,3,11,15]. With the fast volume scan technique of multiple spiral CT, reformation in any dimensions is feasible, and the quality of the reformatted images is almost as same as the axial ones, which ensures a good overall observation. The finding of lipid attenuation (-100 to -50 HU) is vital to the diagnosis of a lipoma[17,18]. CT examination revealed lipid-attenuated (-130 to -60 HU) intraluminal masses in all patients of our series (Figure 2B), the location and range of the tumors and the accompanying intussusception were also displayed clearly and directly on the two-dimensional (2D) CT enterography (Figure 1C and Figure 3), which helped establish a correct prospective diagnosis. For the other misdiagnosed cases, post-operational recognization of the reformatted CT images with regulated windows still retrospectively showed the tumor existence. It is important to stress that adequate oral contrast media is necessary for filling the small bowel and optimal windows is also needed to avoid mistaking lipomas for intraluminal gas. Observation of the images reformatted in multiple dimensions is helpful in differentiation lipomas from invaginated mesenteric fat when there is an intestinal intussusception.

The role of MR imaging in the evaluation of small bowel lesions is limited due to the lack of effective intestinal contrast media and the presence of motion artifact caused by relatively long scanning time and intestinal peristalsis. With new MR machine, advanced fast scan techniques, fat-saturation imaging and gadolinium chelates application, the resolution of MR images has improved, the clinical and research application on intestinal diseases has increased over recent years, nevertheless there are still few reports in the literature about MR imaging of small bowel lipomas[19,20].

Clinical manifestation is not specific for this rare entity, imaging modalities are helpful for revealing small bowel lipomas, especially the characteristic features at multi-slice CT enterography can be used by the radiologists to establish a definitive diagnosis before operation for most cases. In the instances of secondary intestinal intussusception or obstruction, the primary lesion of a lipoma should be carefully searched out.

Lipomas are benign tumors and may arise from any anatomic location, subcutaneous tissue is the most common site, while lipomas of the alimentary tract especially of the small intestine are rare entities. According to the authors of this paper, only case reports of small bowel lipoma have been presented in the literature.

Primary small bowel tumors are uncommon, which account for about 1% of all gastrointestinal tumors, and primary lipomas of the small intestine are rare. Preoperative diagnosis is usually indeterminate only based on clinical manifestations due to the overlap of symptoms and signs with other intestinal tumors. Benign tumors in the small intestine do not have a characteristic computed tomography (CT) appearance and, in most instances, cannot be differentiated from malignant lesions, but lipomas can be definitively diagnosed by the recognition of fat attenuation within the mass.

The authors presented 15 surgically confirmed small intestinal lipomas and analyzed retrospectively their clinical, pathological and imaging findings, especially multi-slice CT enterography.

Clinical manifestation is not specific for the small intestinal lipomas, imaging modalities are helpful for revealing small bowel lipomas, especially the multi-slice CT enterography which can be used by the radiologists to establish a definitive diagnosis before operation for most cases.

Small bowel lipomas tend to occur in the elderly, and the sixth to seventh decades of life are considered to be the most risky period. Multi-slice CT enterography (MCTE): MCTE is a new non-invasive procedure that uses very fast CT scanning combined with liquid intake to obtain detailed images of the abdomen. CT enterography has several advantages over conventional bowel imaging: it shows the entire thickness of the bowel wall; it is able to image all of the long loops of the small intestine; and it can also evaluate surrounding mesentery and fat tissues. CT enterography has also become an important alternative to traditional fluoroscopy in the assessment of other small bowel disorders such as celiac sprue and small bowel neoplasms.

The authors present 15 surgically confirmed small intestinal lipomas and analyze retrospectively their clinical, pathological and imaging findings.

Peer reviewer: Aydin Karabacakoglu, Assistant Professor, Department of Radiology, Meram Medical Faculty, Selcuk University, Konya 42080, Turkey

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Kiziltaş S, Yorulmaz E, Bilir B, Enç F, Tuncer I. A remarkable intestinal lipoma case. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2009;15:399-402. |

| 2. | Aminian A, Noaparast M, Mirsharifi R, Bodaghabadi M, Mardany O, Ali FA, Karimian F, Toolabi K. Ileal intussusception secondary to both lipoma and angiolipoma: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:7099. |

| 3. | Karadeniz Cakmak G, Emre AU, Tascilar O, Bektaş S, Uçan BH, Irkorucu O, Karakaya K, Ustundag Y, Comert M. Lipoma within inverted Meckel's diverticulum as a cause of recurrent partial intestinal obstruction and hemorrhage: a case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1141-1143. |

| 4. | Du L, Shah TR, Zenilman ME. Image of the month--quiz case. Intussuscepted transverse colonic lipoma. Arch Surg. 2007;142:1221. |

| 5. | Gore RM, Mehta UK, Berlin JW, Rao V, Newmark GM. Diagnosis and staging of small bowel tumours. Cancer Imaging. 2006;6:209-212. |

| 6. | Akagi I, Miyashita M, Hashimoto M, Makino H, Nomura T, Tajiri T. Adult intussusception caused by an intestinal lipoma: report of a case. J Nippon Med Sch. 2008;75:166-170. |

| 7. | Rosai J. Gastrointestinal tract. Rosai and Ackerman’s surgical pathology. New York: Mosby 2004; 739. |

| 8. | Miettinen M, Blay JY, Kindblom LG, Sobin LH. Mesenchymal tumors of the colon and rectum. Pathology and genetics of tumors of the digestive system. Lyon: IARC Press 2000; 142. |

| 9. | Miettinen M, Blay JY, Sobin LH. Mesenchymal tumors of the small intestine. Pathology and genetics of tumors of the digestive system. Lyon: IARC Press 2000; 90. |

| 10. | Ladurner R, Mussack T, Hohenbleicher F, Folwaczny C, Siebeck M, Hallfeld K. Laparoscopic-assisted resection of giant sigmoid lipoma under colonoscopic guidance. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:160. |

| 11. | Jayaraman MV, Mayo-Smith WW, Movson JS, Dupuy DE, Wallach MT. CT of the duodenum: an overlooked segment gets its due. Radiographics. 2001;21 Spec No:S147-S160. |

| 12. | Kakitsubata Y, Kakitsubata S, Nagatomo H, Mitsuo H, Yamada H, Watanabe K. CT manifestations of lipomas of the small intestine and colon. Clin Imaging. 1993;17:179-182. |

| 13. | Oyen TL, Wolthuis AM, Tollens T, Aelvoet C, Vanrijkel JP. Ileo-ileal intussusception secondary to a lipoma: a literature review. Acta Chir Belg. 2007;107:60-63. |

| 14. | Costanzo A, Patrizi G, Cancrini G, Fiengo L, Toni F, Solai F, Arcieri S, Giordano R. [Double ileo-ileal and ileo-cecocolic intussusception due to submucous lipoma: case report]. G Chir. 2007;28:135-138. |

| 15. | Tsushimi T, Matsui N, Kurazumi H, Takemoto Y, Oka K, Seyama A, Morita T. Laparoscopic resection of an ileal lipoma: Report of a case. Surg Today. 2006;36:1007-1011. |

| 16. | Heiken JP, Forde KA, Gold RP. Computed tomography as a definitive method for diagnosing gastrointestinal lipomas. Radiology. 1982;142:409-414. |

| 17. | Ross GJ, Amilineni V. Case 26: Jejunojejunal intussusception secondary to a lipoma. Radiology. 2000;216:727-730. |

| 18. | Drop A, Czekajska-Chehab E, Maciejewski R. Giant retroperitoneal lipomas--radiological case report. Ann Univ Mariae Curie Sklodowska Med. 2003;58:142-146. |

| 19. | Fidler J. MR imaging of the small bowel. Radiol Clin North Am. 2007;45:317-331. |

| 20. | Turi S, Röckelein G, Dobroschke J, Wiedmann KH. [Lipoma of the small bowel]. Z Gastroenterol. 2004;42:147-151. |