Published online Jan 14, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i2.232

Revised: December 2, 2009

Accepted: December 9, 2009

Published online: January 14, 2010

AIM: To understand the demographic characteristics of patients in Southwestern Ontario, Canada with ulcerative colitis (UC) in order to predict disease severity.

METHODS: Records from 1996 to 2001 were examined to create a database of UC patients seen in the London Health Sciences Centre South Street Hospital Inflammatory Bowel Disease Clinic. To be included, patients’ charts were required to have information of their disease presentation and a minimum of 5 years of follow-up. Charts were reviewed using standardized data collection forms. Disease severity was generated during the chart review process, and non-endoscopic Mayo Score criteria were collected into a composite.

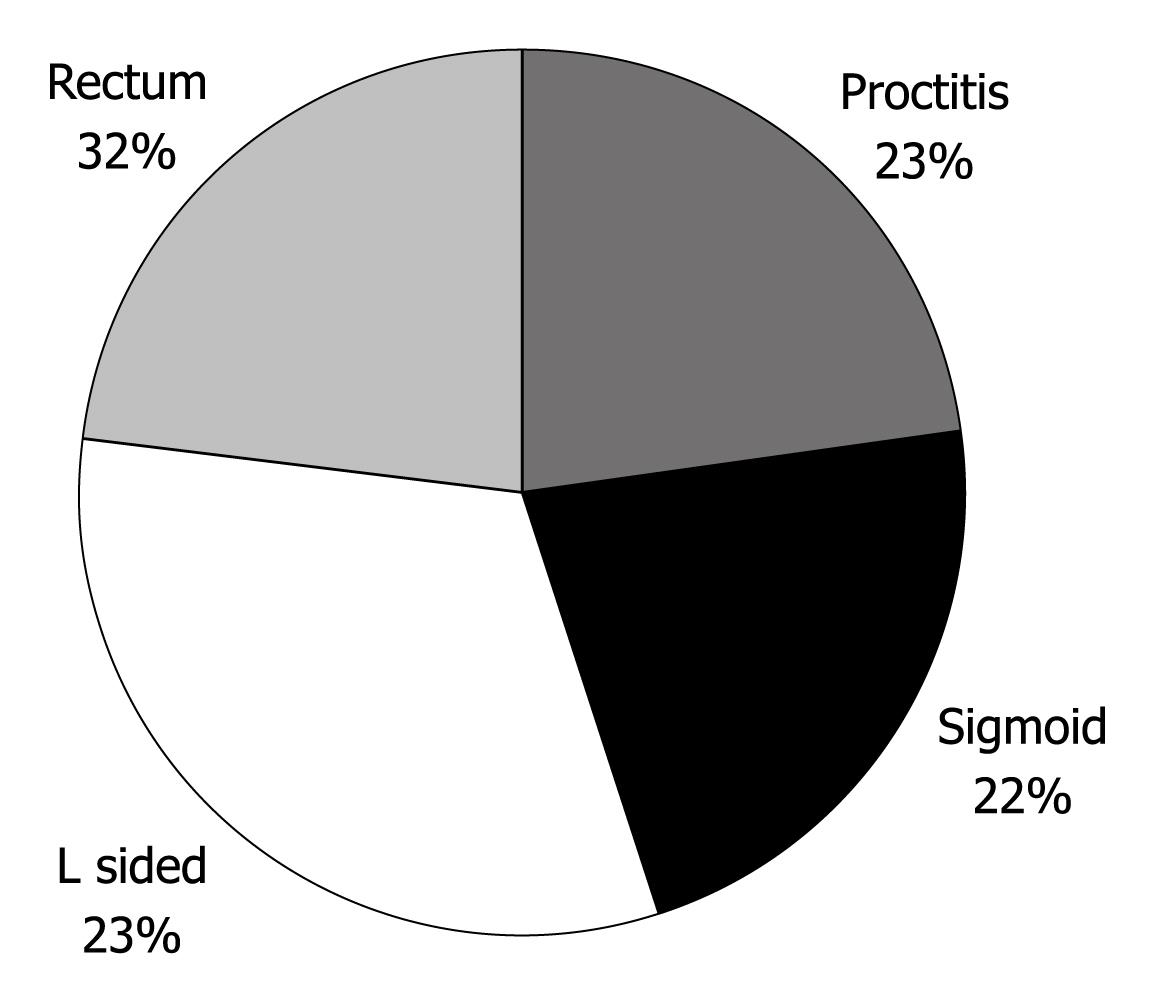

RESULTS: One hundred and two consecutive patients’ data were entered into the database. Demographic analyses revealed that 51% of the patients were male, the mean age at diagnosis was 39 years, 13.7% had a first degree relative with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), 61.8% were nonsmokers and 24.5% were ex-smokers. In 22.5% of patients the disease was limited to the rectum, in 21.6% disease was limited to the sigmoid colon, in 22.5% disease was limited to the left colon, and 32.4% of patients had pancolitis. Standard multiple regression analysis which regressed a composite of physician global assessment of disease severity, average number of bowel movements, and average amount of blood in bowel movements on year of diagnosis and age at time of diagnosis was significant, R2 = 0.306, F (7, 74) = 4.66, P < 0.01. Delay from symptoms to diagnosis of UC, gender, family history of IBD, smoking status and disease severity at the time of diagnosis didnot significantly predict the composite measure.

CONCLUSION: UC severity is associated with younger age at diagnosis and year of diagnosis in a longitudinal cohort of UC patients, and may identify prognostic UC indicators.

- Citation: Roth LS, Chande N, Ponich T, Roth ML, Gregor J. Predictors of disease severity in ulcerative colitis patients from Southwestern Ontario. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(2): 232-236

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i2/232.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i2.232

Canada has one of the highest rates of ulcerative colitis (UC) in the world, with an annual incidence of approximately 3500 cases and a prevalence of roughly 60 000[1]. Each patient with UC is faced with a chronic disease with an uncertain course, experiencing periods of relapse and remission, and often requiring long-term medical therapy. In some cases, however, the disease remains mild or becomes more severe but it is difficult to predict the ultimate course of UC without simply monitoring the patient for years.

Many therapies have been studied over the past 60 years for the treatment of UC, starting with sulfasalazine and hydrocortisone[2], through newer 5-aminosalicylate products[3], immunosuppressives[4,5], and now biological therapies. A treatment pyramid has been proposed, with less potent and more tolerable agents at the bottom and more powerful agents with greater potential toxicities at the top[6]. The recent introduction of infliximab has provided another treatment option for UC patients with refractory disease, but the long-term safety and efficacy of this therapy is unknown[7]. In addition, the substantial cost of biological therapies makes using these agents as initial therapy difficult to justify given the large number of patients who respond to more inexpensive treatments.

Studies examining groups of UC patients have been published from various geographic regions over a number of decades, with many looking at cohorts of UC patients longitudinally[8-11]. Many of these studies, however, were published prior to the introduction of newer therapies and may lack applicability to current UC patients. Furthermore, few studies have looked at Canadian UC patients, and therefore the relevance of these results to our patient population is unknown. The aim of this study was to examine the UC population of Southwestern Ontario (SWO), Canada in an effort to gather information on the natural history of the disease and determine predictors of future disease severity at the time of diagnosis.

Patients with UC seen in the London Health Sciences Centre South Street Hospital Inflammatory Bowel Disease Clinic from 1996-2001 were identified by a search of diagnostic codes. Individual clinic charts for these patients were reviewed to determine if they met the study inclusion criteria, which included a new diagnosis of UC, details of disease presentation at diagnosis, and documentation of follow up for at least 5 years.

Patient data were collected retrospectively from clinic charts using standardized data collection forms created specifically for this study. Demographic data including age, sex, year of diagnosis, age at diagnosis, smoking status, and a family history of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) as well as annual measurements of disease severity and course of disease were recorded.

Disease severity was measured using a modified version of the Mayo Scoring System for assessment of UC activity[12], which excluded the endoscopic component. Values from 0 to 3 were recorded for each of: frequency of bowel movements, amount of blood in bowel movements, and physician assessment of disease severity.

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS 15.0 for a multiple regression analysis of demographic factors on the disease severity composite. Microsoft Excel was used for the data management and averages.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at The University of Western Ontario.

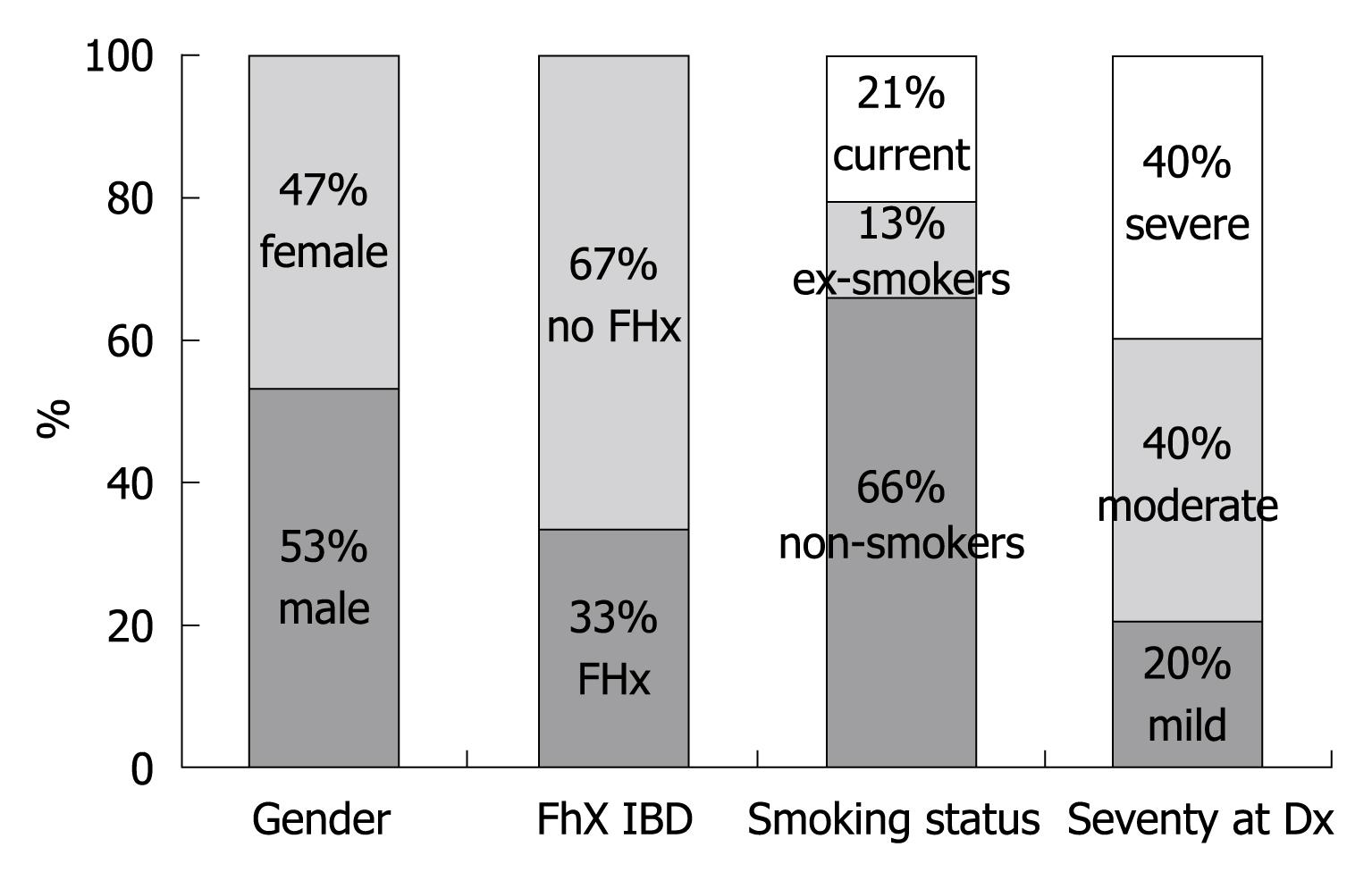

One hundred and two consecutive patient charts who met the inclusion criteria were reviewed. Demographic analyses demonstrated that 51% of the cohort was male, 13.7% had a family history of IBD, and 61.8% were nonsmokers (Table 1). Average delay from time of symptom onset to time of diagnosis was 1.8 years (range 0-34 years; SD = 4.5 years).

| Gender (male/female) | 52 (51)/50 (49) |

| Mean age at diagnosis (yr) | 39 (range 9-85; SD = 17.9) |

| Family history of IBD in 1st degree relative | 14 (13.7) |

| Non-smokers/ex-smokers | 63 (61.8)/25 (24.5) |

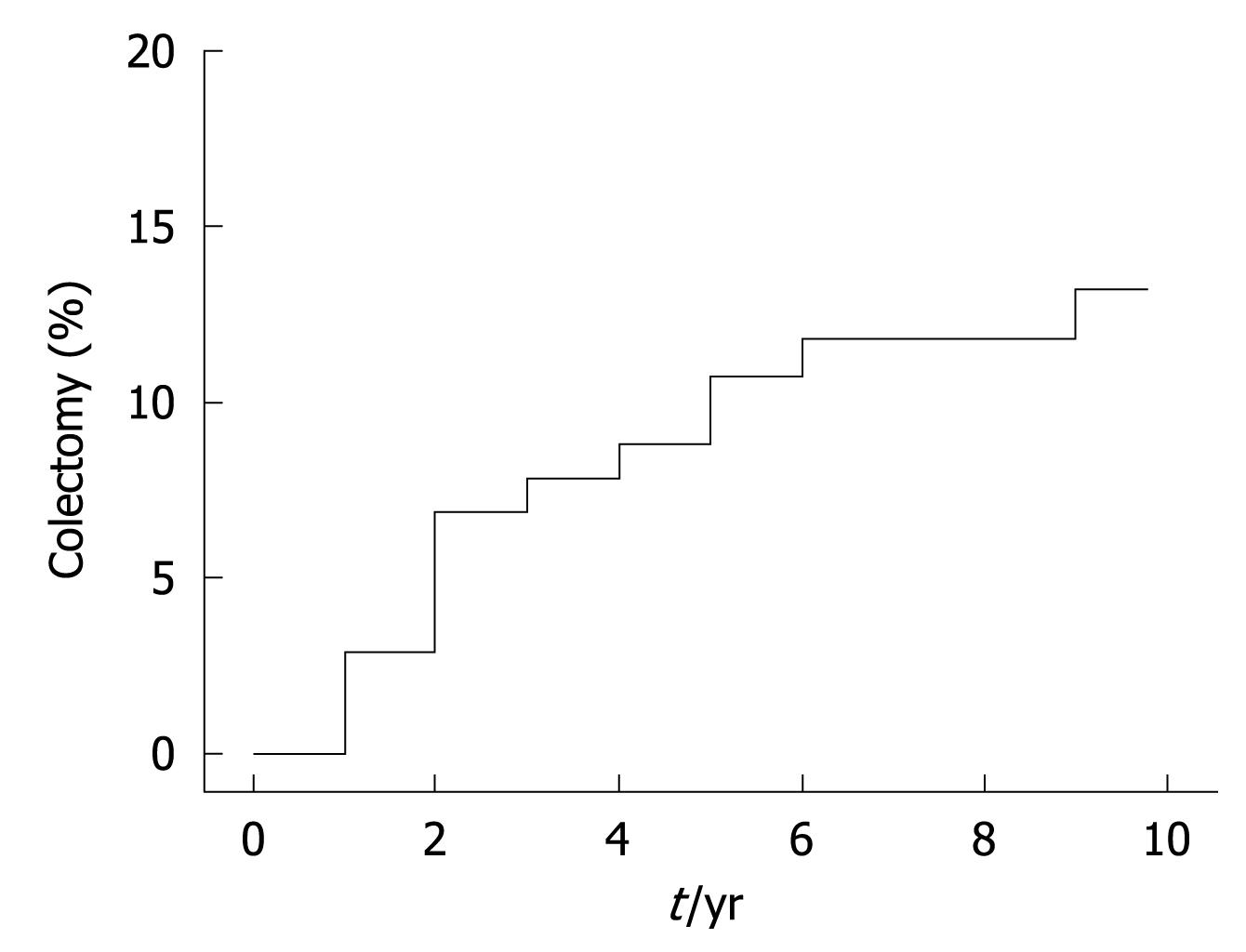

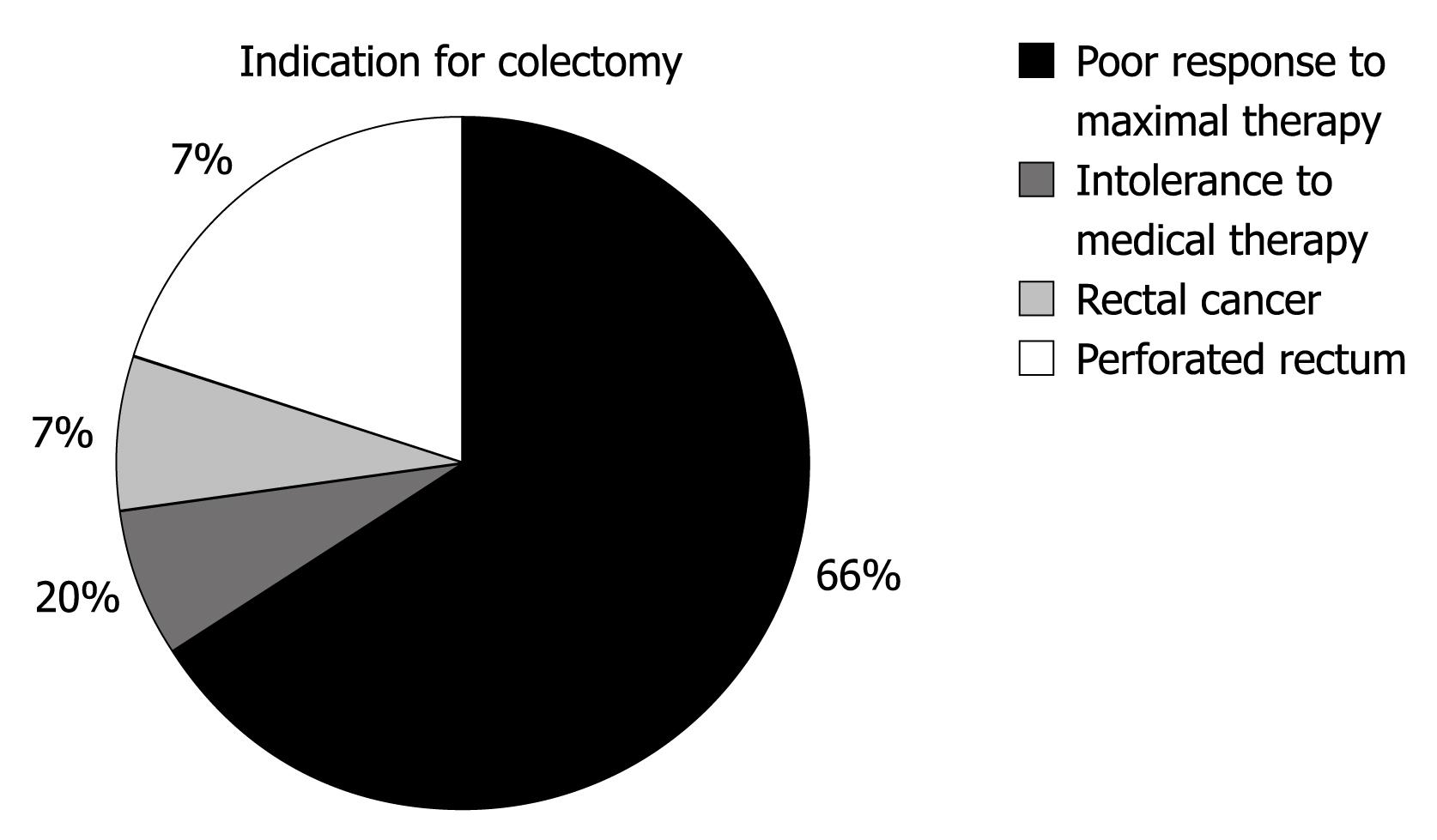

Data examining the extent of disease are shown in Figure 1. Colectomy rates were calculated at 14.7% of the cohort (15 patients), and are plotted against time in Figure 2. Figure 3 outlines the indications for colectomy, while Figure 4 displays the demographics of this group. Seven of these patients underwent an ileal pouch-anal anastomosis with the remaining 8 patients undergoing an ileostomy. Of those who underwent ileal pouch anal-anastomosis, 5 (71%) had at least 1 subsequent episode of pouchitis. In the patients who had a colectomy, 10 patients (66.6%) had pancolitis while disease extent was limited to the sigmoid colon in 4 patients (26.7%) and to the left colon in 1 patient (6.7%). The average composite severity score for this group was 3.24 across at least 5 years of follow up (1.15 for number of bowel movements, 0.85 for blood in bowel movements, and 1.24 for physician global assessment of severity).

Three patients died during the follow up period, two from unrelated malignancies (melanoma and squamous cell lung cancer) and one from congestive heart failure.

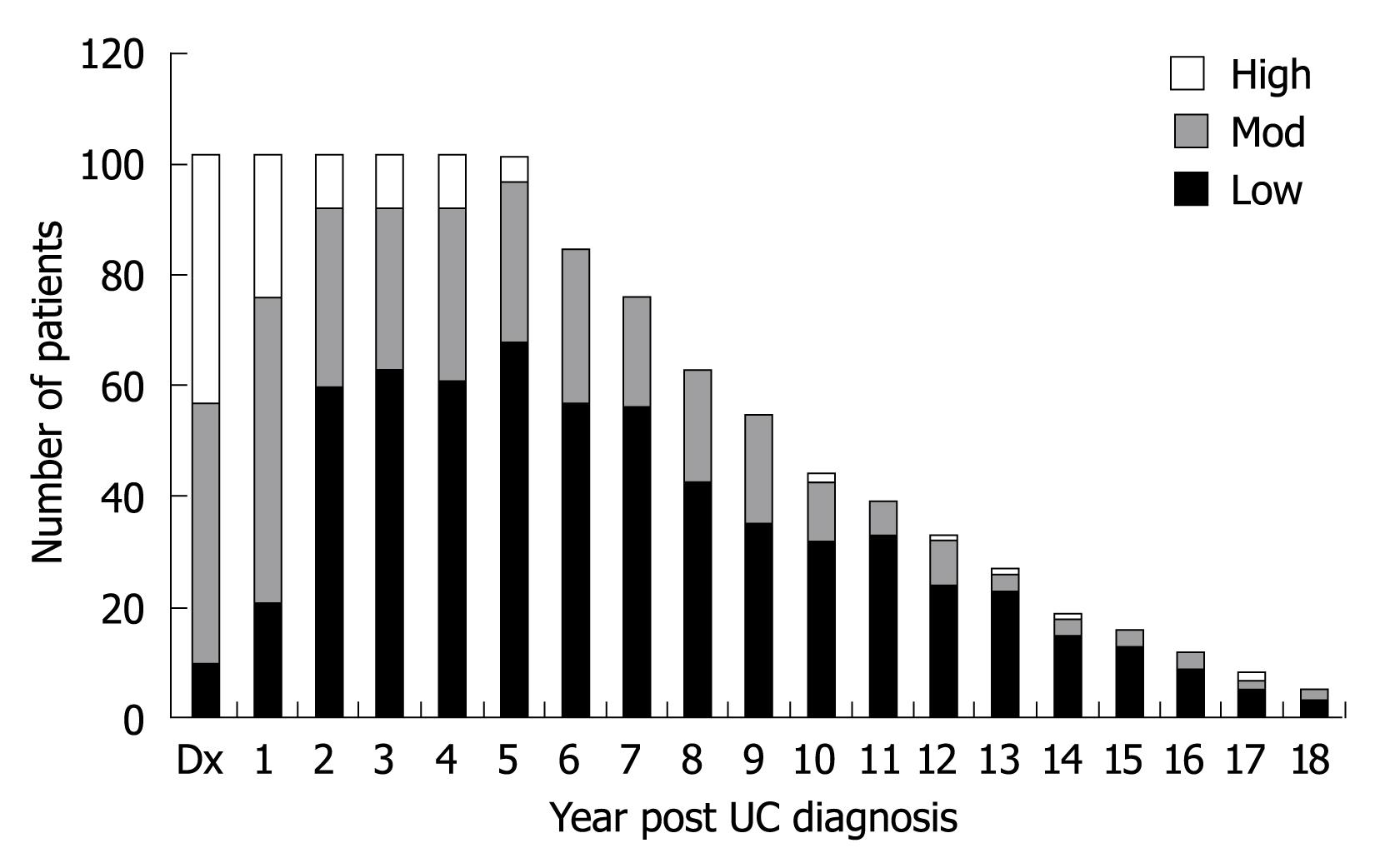

Disease severity was determined for each patient during each year of follow up. All patients except one had complete data for at least 5 years of follow up after diagnosis, with the reviewer unable to assign severity status to one patient during 1 year of follow up. Data are listed in Figure 5 with severity divided into three groups: low (modified Mayo Score 0-2), moderate (modified Mayo Score 3-5), and high (modified Mayo Score 6-9).

The composite of disease severity was averaged across the number of years with UC, with a mean value for the cohort of 2.12 (standard deviation 1.18; minimum 0.36; maximum 6.22). When grouped into categories of severity, 77.5% (79 patients) had an average score of less than three, 21.5% (22 patients) had an average score between three and six, and 1% (1 patient) had an average score of greater than six.

Pearson product moment correlation analyses were conducted in order to evaluate the extent of interrelationship between the composite value of disease severity and demographic variables. Demographic variables included year of diagnosis, delay from symptom onset to diagnosis, gender, smoking status at time of diagnosis, family history of IBD in a first degree relative, severity at diagnosis, and age at diagnosis. Year of diagnosis was positively associated with the composite of disease severity [r (102) = 0.35, P < 0.01], such that a more recent year of diagnosis was associated with a higher composite score. Smoking status at time of diagnosis [r (97) = -0.22, P < 0.05] and age at diagnosis [r (102) = -0.32, P < 0.01] were negatively associated with the composite score of disease severity, such that current smokers and younger patients had a higher composite score.

Regression analysis was performed on the composite value of disease severity on various demographic variables. Standard multiple regression analyses on year of diagnosis and age at time of diagnosis were significant, R2 = 0.306, F (7, 74) = 4.66, P < 0.01. The correlation indicated that more severe disease was present in those diagnosed at an earlier age, and those diagnosed more recently had a worse course of disease. Delay from symptoms to diagnosis of UC, gender, family history of IBD, smoking status and disease severity at the time of diagnosis didnot significantly predict the composite measure.

UC is a chronic disease with a variable and uncertain course. Patients diagnosed with the disease have no means to predict whether their disease will be ongoing, consist of severe relapses, or remain indolent. Previous studies have looked at the natural course of UC, however, this study has the added benefit of following a fairly large cohort of patients with UC for a minimum of 5 years. Demographics such as disease extent, gender, and presence of a family history of IBD compare favorably with the cohort from Farmer’s 1992 study of over 1000 individuals from the Cleveland Clinic[8]. Previously reported colectomy rates range from 8.7% in a recent European trial[9], to 45% in a Swedish study from 1990[11]. Our value of 15% lies well within this range, and indeed, is comparable to the Northern European portion of the aforementioned study. This allows some quality assurance that patients in the SWO IBD clinic have similar demographics and outcomes to other areas of the world.

The Mayo Scoring System[12] is a validated tool that measures disease activity in patients with UC. We applied this tool to UC patients at diagnosis and during follow-up in an effort to determine which demographic variables could predict long term disease activity. The endoscopy score was excluded from this tool as sigmoidoscopy/colonoscopy was not routinely performed on a regular basis in most patients. Thus the score was out of a maximum of 9 rather than 12. Some scales, such as the Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index[13] and Seo et al[14] index do not rely on endoscopic scores, while other scores such as the Ulcerative Colitis Disease Activity Index and St. Mark’s index[15] incorporate an endoscopic component into their values. In a comparison between those scores that contain endoscopy related elements against those that didnot, it was found that endoscopy added little additional information to the assessment of disease activity[16]. Therefore, the use of the Mayo score without the endoscopic system is likely a valid alternative.

We found that younger age at diagnosis predicts a more severe future disease course. Previous studies have shown that patients with early onset UC are more prone to colorectal cancer[17], however the finding that severity of future disease is predicted is not widely prevalent in the current literature. One theory that has arisen in discussion as well as at presentations is that the more severe the disease, the earlier it unmasks itself clinically. This then leads to more symptoms during the patient’s follow up and a worse course clinically for the patient.

While younger age at diagnosis seems to play a significant role in predicting disease severity, so does the year of diagnosis. It is difficult to tease out the fine nuances of younger age and year of diagnosis, as these obviously affect each other. It would seem from the analysis, however, that the year independently predicts the outcome, and therefore we have to consider that as our arsenal for UC has grown, perhaps our treatment of this condition has not improved as much as we originally thought. An alternative explanation could be found in the fact that all patients in this study were seen in a rapidly growing IBD clinic in a tertiary care referral centre, and perhaps the severity of cases has been high with mild or moderate cases being managed by community practitioners.

The above variables predicted future disease severity, however, there were a number of factors not found to be predictive. One of the most intriguing was smoking status, as multiple previous studies have found that smoking was a protective factor[18], while non- or ex-smokers had a higher risk of relapsing disease[19]. In addition, disease severity at presentation didnot correlate with the severity index over the disease course, nor did delay from diagnosis to treatment. This was unexpected, as literature by Sandborn[20] found that classifying presentations into one of four severity categories was useful for prognosticating disease. In addition, gender and family history all seemed to have a minimal role in predicting future disease.

The limitations of the study make a large sweeping commentary on our prediction of UC difficult. It is retrospective in design, and relies heavily on chart review. The number of patients in the study compares favorably with many previous reviews of UC and contains patients with similar disease extent and severity, but with just over 100 patients it is difficult to be certain of the effect in a larger group. Additionally, the geographic nature of the population may make it hard to extract information on other populations in Canada or the rest of the world.

The information provided by the demographic variables is valuable in many ways. Firstly, to the patient this may alleviate much of the sense of unknown, and allow them to cope with the diagnosis and treatment more effectively. In addition to this, however, it allows the clinician to triage which patients may progress more quickly and customize their therapy accordingly. For instance, if a younger patient presents with confirmed UC, one may be more willing to adopt a “top down” approach and start them on anti-TNF agents immediately. This may help save time, patient discomfort, and reduce the risk of outcomes such as colectomy in that severe symptoms do not have the potential to develop. Rather than navigate patients through the pyramid of UC agents, this would guide patients to the agent most suited to their specific condition.

This study provides evidence that predictors of disease severity in UC may exist in simple demographic information that is available to any clinician and may help ease the unpredictability of this condition as well as help physicians treat patients with tailored therapy. Additional studies looking prospectively at patients with UC in an effort to help predict disease severity would be most useful and easily conducted.

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an inflammatory disease of the large intestine that affects many Canadians. The individuals, often young and in the prime of their life, experience symptoms such as diarrhea, bleeding from the bowels, and abdominal discomfort. They can expect periods of health interrupted by worsening of their disease, with some having very serious symptoms and others having minimal to no symptoms.

The natural history of the disease has been looked at in previous studies, but predicting which patients will have severe disease and which will have mild disease has not been fully examined.

This article describes a Canadian population of patients with UC that have been followed for at least 5 years, and looked back to see if any of their characteristics, such as age, gender, smoking status, delay to diagnosis, year of diagnosis or the manner in which they presented, predicted how they will progress in coming years. Age at diagnosis and year of diagnosis seemed to predict the disease course, with a younger age at diagnosis and a more recent year of diagnosis predicting a more severe disease pattern.

These findings allow physicians to give patients newly diagnosed with UC an idea of what to expect in the coming years. Although not completely predictive, those patients who present with UC who are younger may expect a more severe disease course. Physicians treating these patients may be more inclined to start stronger therapies initially in these patients.

The original manuscript by Roth et al is a very interesting and a very well written manuscript. It is a retrospective study, with a good attempt to find out the predictors of severity from the demographic parameters. The paper is nicely laid out with a very good selection of references and nicely addressed limitations. A retrospective study, it is a good attempt to find out the predictors of severity from the demographic parameters.

Peer reviewers: Wojciech Blonski, MD, PhD, University of Pennsylvania, GI Research-Ground Centrex, 3400 Spruce St, Philadelphia, PA 19104, United States; Dr. Ashok Kumar, MD, Department of Surgical Gastroenterology, Sanjay Gandhi Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow 226014, India

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Bernstein CN, Wajda A, Svenson LW, MacKenzie A, Koehoorn M, Jackson M, Fedorak R, Israel D, Blanchard JF. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1559-1568. |

| 2. | Truelove SC, Witts LJ. Cortisone in ulcerative colitis; final report on a therapeutic trial. Br Med J. 1955;2:1041-1048. |

| 3. | Sutherland L, Macdonald JK. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;CD000543. |

| 4. | Timmer A, McDonald JW, Macdonald JK. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;CD000478. |

| 5. | Chande N, MacDonald JK, McDonald JW. Methotrexate for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;CD006618. |

| 6. | Velayos FS, Sandborn WJ. Positioning biologic therapy for Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2007;9:521-527. |

| 7. | Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J, Travers S, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB, Lichtenstein GR. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462-2476. |

| 8. | Farmer RG, Easley KA, Rankin GB. Clinical patterns, natural history, and progression of ulcerative colitis. A long-term follow-up of 1116 patients. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1137-1146. |

| 9. | Hoie O, Wolters FL, Riis L, Bernklev T, Aamodt G, Clofent J, Tsianos E, Beltrami M, Odes S, Munkholm P. Low colectomy rates in ulcerative colitis in an unselected European cohort followed for 10 years. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:507-515. |

| 10. | Langholz E, Munkholm P, Davidsen M, Binder V. Colorectal cancer risk and mortality in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1444-1451. |

| 11. | Leijonmarck CE. Surgical treatment of ulcerative colitis in Stockholm county. Acta Chir Scand Suppl. 1990;554:1-56. |

| 12. | Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625-1629. |

| 13. | Walmsley RS, Ayres RC, Pounder RE, Allan RN. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut. 1998;43:29-32. |

| 14. | Seo M, Okada M, Yao T, Ueki M, Arima S, Okumura M. An index of disease activity in patients with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:971-976. |

| 15. | Powell-Tuck J, Bown RL, Lennard-Jones JE. A comparison of oral prednisolone given as single or multiple daily doses for active proctocolitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1978;13:833-837. |

| 16. | Higgins PD, Schwartz M, Mapili J, Zimmermann EM. Is endoscopy necessary for the measurement of disease activity in ulcerative colitis? Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:355-361. |

| 17. | Eaden JA, Abrams KR, Mayberry JF. The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2001;48:526-535. |

| 18. | Calkins BM. A meta-analysis of the role of smoking in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:1841-1854. |

| 19. | Höie O, Wolters F, Riis L, Aamodt G, Solberg C, Bernklev T, Odes S, Mouzas IA, Beltrami M, Langholz E. Ulcerative colitis: patient characteristics may predict 10-yr disease recurrence in a European-wide population-based cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1692-1701. |

| 20. | Sandborn WJ. Severe Ulcerative Colitis. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 1999;2:113-118. |