Published online Mar 7, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1099

Revised: January 14, 2009

Accepted: January 21, 2009

Published online: March 7, 2009

AIM: To identify clinical parameters, and develop an Upper Gastrointesinal Bleeding (UGIB) Etiology Score for predicting the types of UGIB and validate the score.

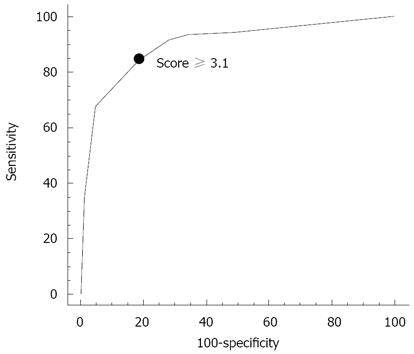

METHODS: Patients with UGIB who underwent endoscopy within 72 h were enrolled. Clinical and basic laboratory parameters were prospectively collected. Predictive factors for the types of UGIB were identified by univariate and multivariate analyses and were used to generate the UGIB Etiology Score. The best cutoff of the score was defined from the receiver operating curve and prospectively validated in another set of patients with UGIB.

RESULTS: Among 261 patients with UGIB, 47 (18%) had variceal and 214 (82%) had non-variceal bleeding. Univariate analysis identified 27 distinct parameters significantly associated with the types of UGIB. Logistic regression analysis identified only 3 independent factors for predicting variceal bleeding; previous diagnosis of cirrhosis or signs of chronic liver disease (OR 22.4, 95% CI 8.3-60.4, P < 0.001), red vomitus (OR 4.6, 95% CI 1.8-11.9, P = 0.02), and red nasogastric (NG) aspirate (OR 3.3, 95% CI 1.3-8.3, P = 0.011). The UGIB Etiology Score was calculated from (3.1 × previous diagnosis of cirrhosis or signs of chronic liver disease) + (1.5 × red vomitus) + (1.2 × red NG aspirate), when 1 and 0 are used for the presence and absence of each factor, respectively. Using a cutoff ≥ 3.1, the sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) in predicting variceal bleeding were 85%, 81%, 82%, 50%, and 96%, respectively. The score was prospectively validated in another set of 195 UGIB cases (46 variceal and 149 non-variceal bleeding). The PPV and NPV of a score ≥ 3.1 for variceal bleeding were 79% and 97%, respectively.

CONCLUSION: The UGIB Etiology Score, composed of 3 parameters, using a cutoff ≥ 3.1 accurately predicted variceal bleeding and may help to guide the choice of initial therapy for UGIB before endoscopy.

- Citation: Pongprasobchai S, Nimitvilai S, Chasawat J, Manatsathit S. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding etiology score for predicting variceal and non-variceal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(9): 1099-1104

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i9/1099.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.1099

Upper Gastrointesinal Bleeding (UGIB) is a common gastrointestinal emergency and carries a mortality rate of 5%-14%[1]. The causes of UGIB have been classified into variceal bleeding (esophageal and gastric varices) and non-variceal bleeding (peptic ulcer, erosive gastroduodenitis, reflux esophagitis, tumor, vascular ectasia, etc). Currently, emergency esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is the standard investigation of choice for active UGIB since it provides both diagnosis and treatment of UGIB[2–11]. However, in the real life situation, emergency EGD is seldom available in most hospitals due to the difficulty of setting up emergency services in non-official time, an insufficiency of well-trained endoscopists and medical teams and lack of equipment. Thus, most patients are usually treated medically for a period of time before being referred for EGD at the centers with available facilities.

Some practice guidelines on non-variceal bleeding[56], variceal bleeding[1213] including Thai guidelines in 2004[14] recommend giving empirical treatments to patients with UGIB while waiting for EGD. If variceal bleeding is suspected, empirical treatment with vasoactive agents (e.g. somatostatin, octreotide, terlipressin, etc) is strongly recommended, since they can stop bleeding in up to 70%-80% of cases and a decrease in mortality has been shown with some agents (i.e. terlipressin)[1213]. In contrast, for suspected non-variceal bleeding, empirical treatment with a high-dose proton pump inhibitor is recommended since it reduces the stigmata of recent hemorrhage[51516].

From a clinical viewpoint, to diagnose variceal bleeding precisely and to promptly administer vasoactive drugs to these patients, is crucial because variceal bleeding has a very high early mortality rate of up to 30% and up to 47%-74% of patients will have recurrent bleeding[1213]. To predict which patients have variceal bleeding is not always easy. Some authors have suggested that the clinical signs of cirrhosis or portal hypertension[17–19], painless hematemesis and bleeding with significant change in hemodynamics may indicate variceal bleeding. In contrast, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) users, the presence of dyspepsia or coffee-ground NG aspirate have been suggested to favor non-variceal bleeding[1819]. These suggestions are often expert opinions and have never been formally validated.

The aims of this study are to assess the clinical and basic laboratory parameters which may help differentiate variceal and non-variceal bleeding before performing EGD, to develop a model of the UGIB Etiology Score for predicting the cause of UGIB based on clinical parameters and to validate the accuracy of this suggested score.

All consecutive patients who presented with acute UGIB at Siriraj Hospital from June 2006 to December 2007 were prospectively enrolled into the study. Patients who presented in the initial period during June 2006 to December 2006 were included for score derivation purposes and patients who presented in the later period during May 2007 to December 2007 were included for score validation. The inclusion criteria were: 1. UGIB, defined by the presence of hematemesis, melena or hematochezia, and a positive NG tube aspiration for coffee-ground, black or bloody contents 2. EGD within 72 h after the onset of UGIB 3. Patients aged ≥ 18 years. An exclusion criterion was patients whose definite cause of UGIB was undetermined or inconclusive during EGD.

Data were collected by gastroenterology fellows at the time of the patients’ presentation. Patients’ history included age, gender, appearance of vomitus, (red bloody, coffee-ground, clear), appearance of stool (red or maroon stool, melena, brown or yellow stool), presence of dyspepsia or abdominal pain, underlying cirrhosis, history of previous variceal or non-variceal bleeding within 1 year), comorbid diseases (e.g. acute or chronic kidney diseases, diabetes, hypertension, cardiac diseases, chronic lung diseases, and cerebrovascular diseases, etc), history of medications used within 4 wk (i.e. NSAIDS, aspirin, anticoagulants, corticosteroids and alcohol).

Physical examinations included blood pressure at presentation (presence of shock or BP < 90/60 mmHg), heart rate at presentation (presence of tachycardia, HR > 100 beats/min), degree of pallor (marked, mild/moderate, none), findings on NG tube aspiration (red blood, coffee-ground, clear), findings on rectal examination (red or maroon stool, melena, brownish to yellowish stool), the presence of any sign of chronic liver disease (spider angioma, palmar erythema, gynecomastia, testicular atrophy or parotid gland enlargement), epigastric tenderness, ascites, splenomegaly, and hepatic encephalopathy.

Laboratory data included hemoglobin, hematocrit, white blood cell count, platelet count, BUN, creatinine, prothrombin time, and a panel of liver chemistry tests.

EGD was performed within 72 h of admission in all cases. Causes of bleeding were classified into variceal (esophageal or gastric varices) and non-variceal (e.g. peptic ulcer, erosive gastroduodenitis, reflux esophagitis, tumor, vascular ectasia, etc).

Statistical analysis was performed by using SPSS Program version 13.0. Univariate analysis for the associations between clinical parameters and the types of UGIB was carried out using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variable data. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Logistic regression analysis to identify independent parameters was performed and is presented with odds ratio and 95% confidence interval.

The UGIB Etiology Score was developed from the parameters derived from the multivariate analysis. The best cutoff of the score was chosen from the receiver operating curve (ROC) and the sensitivity and specificity for predicting the types of UGIB were calculated. The score was then tested in the validation group and the positive (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated.

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Siriraj Hospital.

There were 261 patients enrolled into the score derivation group, of which 214 patients (82%) had non-variceal and 47 (18%) had variceal bleeding according to EGD findings. None had negative or inconclusive causes of UGIB by EGD. The causes of non-variceal bleeding were gastric ulcer (39%), duodenal ulcer (22%), both gastric and duodenal ulcer (9%), erosive gastroduodenitis (12%), GI malignancies (5%), Mallory-Weiss syndrome (3%), reflux esophagitis (2%) and miscellaneous (8%). The causes of variceal bleeding were esophageal varices (89%) and gastric varices (11%). Clinical characteristics and laboratory data of the 2 groups together with the univariate analysis of the associations between these factors and the causes of UGIB are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

| Clinical parameter | Cause of UGIB | P | |

| Variceal (n = 47) | Nonvariceal (n = 214) | ||

| Age, mean ± SD (yr) | 53 ± 15 | 61 ± 15 | 0.001 |

| Male | 41 (87) | 151 (71) | 0.030 |

| Character of vomitus | < 0.001 | ||

| Red | 28 (60) | 39 (18) | |

| Coffee-ground or clear | 19 (40) | 175 (82) | |

| Stool appearance | 0.220 | ||

| Red or maroon | 6 (13) | 14 (6) | |

| Melena, brown or yellow | 41 (87) | 200 (93) | |

| Dyspepsia or abdominal pain | 3 (6) | 45 (21) | 0.032 |

| NSAID, ASA, anticoagulant use | 10 (21) | 114 (53) | < 0.001 |

| Previously diagnosed cirrhosis | 17 (36) | 41 (19) | < 0.001 |

| History of variceal bleeding | 13 (28) | 8 (4) | < 0.001 |

| History of non-variceal bleeding | 0 (0) | 21 (10) | 0.018 |

| Comorbid illness | 13 (28) | 132 (62) | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol drinking | 14 (30) | 43 (20) | 0.207 |

| Hypotension | 13 (28) | 39 (18) | 0.206 |

| Tachycardia | 26 (55) | 93 (44) | 0.188 |

| Epigastric tenderness | 2 (4) | 25 (12) | 0.212 |

| Signs of chronic liver disease | 30 (64) | 32 (15) | < 0.001 |

| Splenomegaly | 15 (32) | 14 (6) | < 0.001 |

| Ascites | 20 (43) | 20 (9) | < 0.001 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 7 (15) | 10 (5) | 0.018 |

| Character of NG aspirate | < 0.001 | ||

| Red | 28 (60) | 38 (18) | |

| Coffee-ground or clear | 19 (40) | 176 (82) | |

| Laboratory findings | Causes of UGIB | P | |

| Variceal (n = 47) | Nonvariceal (n = 214) | ||

| Hemoglobin, (g/dL) | 8.6 ± 2.2 | 8.5 ± 2.6 | 0.731 |

| Hematocrit, (%) | 25.8 ± 6.3 | 25.9 ± 7.3 | 0.965 |

| WBC (× 103/ mm3) | 12.2 ± 8.7 | 14.3 ± 13.5 | 0.319 |

| Platelets (× 103/mm3) | 165.0 ± 115.8 | 248.6 ± 129.9 | < 0.001 |

| < 100 × 103/mm3 | 16 (34) | 23 (11) | < 0.001 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 31 ± 18 | 44 ± 29 | 0.003 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 1.6 ± 1.8 | 0.190 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 0.001 |

| Globulin (g/L) | 3.7 ± 0.9 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | < 0.001 |

| Albumin/globulin ratio < 1 | 38 (81) | 83 (45) | < 0.001 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 4.1 ± 5.8 | 2.3 ± 5.5 | 0.054 |

| SGOT (U/L) | 133 ± 187 | 62 ± 107 | 0.001 |

| > 2 × UNL | 25 (53) | 36 (20) | < 0.001 |

| SGPT (U/L) | 62 ± 76 | 36 ± 50 | 0.003 |

| > 2 × UNL | 8 (21) | 21 (12) | 0.359 |

| SGOT/SGPT > 1 | 43 (92) | 132 (75) | 0.025 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 158 ± 112 | 115 ± 105 | 0.015 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 21 ± 11 | 16 ± 8 | 0.002 |

| > 12.5 s | 44 (94) | 58 (29) | < 0.001 |

Variceal bleeding occurred significantly more often than non-variceal bleeding in younger patients (mean age 52.7 vs 60.8 years). Patients with variceal bleeding commonly presented with red bloody vomitus (60% vs 18%), red NG aspirate (60% vs 18%), were often previously diagnosed with cirrhosis (36% vs 19%), often had signs of chronic liver disease (64% vs 15%), splenomegaly (32% vs 6%) and hepatic encephalopathy (15% vs 5%). Patients with non-variceal UGIB more commonly had comorbid diseases (62% vs 28%), a history of ulcerogenic drug use (53% vs 21%) and dyspeptic symptoms (21% vs 6%) as compared to those with variceal bleeding. Hemodynamic changes (hypotension or tachycardia) at presentation were not significantly different between patients with variceal and non-variceal bleeding.

Eighty-two patients were either previously diagnosed with cirrhosis or had signs of chronic liver disease; however, only 40 (49%) of these patients had variceal bleeding.

Patients with variceal bleeding had lower platelet counts, and albumin level, but more commonly had reverse albumin/globulin ratio (81% vs 45%), and higher mean AST and ALT levels (133 vs 62 U/L and 62 vs 36 U/L, respectively). Prolonged prothrombin time was found in 94% of patients with variceal bleeding as compared to 29% of patients with non-variceal bleeding.

Multivariate analysis was performed by a stepwise logistic regression analysis. Three factors were found to be independently associated with variceal bleeding; previous diagnosis of cirrhosis or signs of chronic liver disease (OR 22.4, 95% CI 8.3-60.4, P < 0.001), red vomitus (OR 4.6, 95% CI 1.8-11.9, P = 0.020) and red NG aspirate (OR 3.3, 95% CI 1.3-8.3, P = 0.011) as shown in Table 3.

| Parameter | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P |

| Previous diagnosis of cirrhosis or signs of chronic liver disease | 22.4 | 8.3-60.4 | < 0.001 |

| Red vomitus | 4.6 | 1.8-11.9 | 0.020 |

| Red NG aspirate | 3.3 | 1.3-8.3 | 0.011 |

Using the 3 independent factors, the formulation for calculating the UGIB Etiology Score was constructed for the prediction of variceal bleeding. The formulation was as follow:

UGIB Score = (3.1 × previous diagnosis of cirrhosis or the presence of signs of chronic liver disease) + (1.5 × presence of red vomitus) + (1.2 × presence of red NG aspirate).

To calculate the score, a previous diagnosis of cirrhosis or the presence of signs of chronic liver diseases was scored 1 if present and 0 if absent. Red vomitus was scored 1 if present and 0 if absent. Similarly, red NG aspirate was scored 1 if present and 0 if absent.

Using the receiver operating curve (ROC) in Figure 1, a cutoff ≥ 3.1 was chosen as the best cutoff for predicting variceal bleeding. The sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, PPV and NPV for variceal bleeding with this cutoff were 85%, 81%, 82%, 50% and 96%, respectively.

The UGIB Etiology score was prospectively validated in another set of 195 patients with UGIB. Forty-six patients had variceal and 149 had non-variceal bleeding. None had negative or inconclusive etiologies of UGIB by EGD. The 3 clinical parameters are shown in Table 4. The PPV and NPV of the UGIB Etiology Score for predicting variceal bleeding in the validation group using the same cutoff of ≥ 3.1 were 79% and 97%, respectively.

| Clinical parameter | Cause of UGIB | |

| Variceal (n = 46) | Non-variceal (n = 149) | |

| Age (yr) | 64.51 ± 16 | 56.43 ± 14 |

| Male | 31 (67) | 76 (51) |

| Previous diagnosis of cirrhosis or signs of chronic liver disease | 35 (76) | 12 (8) |

| Red vomitus | 33 (72) | 27 (18) |

| Red NG aspirate | 23 (50) | 21 (14) |

In the present study, the value of clinical and basic laboratory parameters for predicting the types of UGIB (variceal or non-variceal bleeding) was assessed before endoscopy. The present study differs considerably from other previously published studies on the use of clinical predictors in patients with UGIB, as most studies were aimed at predicting the risk of worst outcome or mortality from UGIB in order to triage patients for appropriate care. These studies similarly demonstrated that clinical parameters (e.g. hemodynamics[1720–23], comorbid illnesses[1720–23], NG aspirate[172425]), endoscopic findings (stigmata of recent hemorrhage[1721–2326], and the presence of varices[1721–23]) were strongly associated with the worst outcome, the need for hospitalization or interventions. Multiple scoring systems in UGIB, e.g. the Rockall score[21], Baylor bleeding score[22], Blatchford score[20], Cedars-Sinai score[23] and other scoring systems[27] including a scoring system in Thai patients[28] were also developed for these purposes. In contrast, the present study aimed to determine clinical parameters for use in a scoring system to predict the types of UGIB. Results of the present study may help physicians, particularly those in general practice, where emergency EGD is often unavailable, to decide on the type of empiric treatment more accurately, i.e. the use of pharmacological treatments and in some situations, the use of balloon tamponade in cases with a very high likelihood of severe variceal bleeding.

The present study demonstrated that variceal and non-variceal bleeding have many significant distinct features; but only 3 independent factors were able to predict variceal bleeding, i.e. previous diagnosis of cirrhosis or the signs of chronic liver disease, red vomitus, and red NG aspirate. Although these 3 factors are not new findings, our study clearly strengthened and demonstrated the power of these factors. Furthermore, some previously believed predictors, e.g. splenomegaly or thrombocytopenia (for variceal bleeding)[1819] or the presence of dyspepsia (for non-variceal bleeding)[1819] were found not to be useful due to rarity or weak associations. Other factors, particularly the severity of hemodynamic changes at presentation were also found to be an indistinguishable factor.

In the present study, the UGIB Etiology Score was developed from these 3 clinical parameters. Using a cutoff of ≥ 3.1, the UGIB Score was shown to be accurate in predicting variceal bleeding with a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 81%. The strength of this study is the accuracy of this score which was validated in another set of patients and consistently gave good results. Although a PPV of 79% is not very high, a NPV of 97% for variceal bleeding is very appropriate in the setting of UGIB where variceal bleeding should never be missed. Therefore, a score < 3.1 will help rule out variceal bleeding with confidence.

Since the cutoff of ≥ 3.1 reflected the presence of only one parameter, i.e. previous diagnosis of cirrhosis or the presence of signs of chronic liver disease this may be sufficient to predict variceal bleeding, it may be argued that considering only this parameter might be as accurate as calculating the UGIB Etiology Score. This is probably true; but, considering the other two parameters is also helpful because it increases the PPV of variceal bleeding to 86%-89% with the presence of another parameter and to 96% if all three parameters are present. The latter setting may help physicians to consider balloon tamponade[121329] (which carries significant risks) in cases with severe unstable variceal bleeding when emergency EGD is unavailable or vasoactive agents fail.

Although there have been a few studies on UGIB in Thailand[2830], the present study is the largest prospective study on UGIB in Thailand. The prevalence of variceal bleeding in both study periods was 23%, which was slightly higher than the rate of 6%-14% in the literature[1] and might reflect the tertiary care setting of the present study. However, the present study demonstrated that patients with a history of previously diagnosed cirrhosis or the presence of signs of chronic liver disease had an approximately 50% chance of bleeding from varices. These findings are comparable to those from other studies which showed that 50%-60% of cirrhotic patients with UGIB would bleed from varices[131–33]. Nevertheless, the result of this study and the accuracy of the UGIB Etiology Score should be further validated in other hospitals, where the setting may be different.

In conclusion, the UGIB Etiology Score derived from 3 parameters, using a cutoff ≥ 3.1, may be accurate enough to predict variceal causes of UGIB and may help in guiding the choice of initial therapy for UGIB before endoscopy.

Upper Gastrointesinal Bleeding (UGIB) is classified by etiology into variceal and non-variceal bleeding based on esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) findings. Although emergency EGD is the standard investigation and treatment of UGIB, it is seldom available in most hospitals, particularly in the developing world. Patients are usually treated empirically for some time, while waiting for EGD, with vasoactive agents or acid suppressants based on the clinical suspicion of variceal or non-variceal bleeding, respectively. Therefore, the clinical prediction of which patients have variceal or non-variceal bleeding is critical.

Clinical prediction between variceal and non-variceal bleeding has not been extensively studied. Most suggestions have been based on opinions rather than evidence.

The present study prospectively analyzed the clinical and basic laboratory data which were able to differentiate between variceal and non-variceal bleeding in a group of patients with UGIB. Only 3 independent factors were identified; previous diagnosis of cirrhosis or the presence of signs of chronic liver disease, red vomitus and red NG lavage. The UGIB Etiology Score was constructed and a score cut-off of 3.1 had a fair to good positive predictive value (PPV) but excellent negative predictive value (NPV) to rule out variceal bleeding. The accuracy of the score was also confirmed in another set of patients. The present study differs considerably from most other studies on scoring systems in UGIB which mostly aimed to identify high-risk patients with a poor outcome.

The UGIB Etiology Score ≥ 3.1 had fair to good PPV for variceal bleeding; thus, it can allow physicians to initiate vasoactive agents for variceal bleeding, while a score < 3.1 helped to rule out variceal bleeding with confidence. The presence of all 3 factors or a score of 5.8 indicated variceal bleeding and may be enough for physicians to consider balloon tamponade if bleeding is severe, EGD is unavailable or vasoactive agents fail.

Variceal bleeding is UGIB caused by esophageal or gastric varices. Non-variceal bleeding is caused by any etiology of UGIB other than varices.

This is a nicely performed study aiming to develop and validate a scoring system for predicting variceal vs non-variceal bleeding. The steadily high NPV of the score makes the developed scoring system accurate in excluding variceal bleeding.

| 1. | van Leerdam ME. Epidemiology of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:209-224. |

| 2. | Adler DG, Leighton JA, Davila RE, Hirota WK, Jacobson BC, Qureshi WA, Rajan E, Zuckerman MJ, Fanelli RD, Hambrick RD. ASGE guideline: The role of endoscopy in acute non-variceal upper-GI hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:497-504. |

| 3. | Qureshi W, Adler DG, Davila R, Egan J, Hirota W, Leighton J, Rajan E, Zuckerman MJ, Fanelli R, Wheeler-Harbaugh J. ASGE Guideline: the role of endoscopy in the management of variceal hemorrhage, updated July 2005. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:651-655. |

| 5. | Barkun A, Bardou M, Marshall JK. Consensus recommendations for managing patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:843-857. |

| 6. | Barkun A, Fallone CA, Chiba N, Fishman M, Flook N, Martin J, Rostom A, Taylor A. A Canadian clinical practice algorithm for the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Can J Gastroenterol. 2004;18:605-609. |

| 7. | Celinski K, Cichoz-Lach H, Madro A, Slomka M, Kasztelan-Szczerbinska B, Dworzanski T. Non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding--guidelines on management. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;59 Suppl 2:215-229. |

| 8. | Calabuig Sanchez M, Ramos Espada JM. [Practice guidelines in gastroenterology (VIII). Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage and lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Spanish Society of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Pediatric Nutrition]. An Esp Pediatr. 2002;57:466-479. |

| 9. | Feu F, Brullet E, Calvet X, Fernandez-Llamazares J, Guardiola J, Moreno P, Panades A, Salo J, Saperas E, Villanueva C. [Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;26:70-85. |

| 10. | Brito-Lugo P, Moreno-Terrones L, Bernal-Sahagun F, Gonzalez-Espinola G, Kuri-Guinto J, Lopez-Ureta A, Maranon-Sepulveda M, Santiago-Vazquez L. [Clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Diagnosis]. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2007;72:399-400. |

| 11. | Grau-Cobos L, Arceo-Perez G, Betancourt-Linares R, Compan-Gonzalez F, Hernandez-Guerrero A, Gallo-Reynoso S, Segovia-Gasque Rde J, Lopez-Colombo A. [Clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Treatment]. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2007;72:401-402. |

| 12. | de Franchis R. Evolving consensus in portal hypertension. Report of the Baveno IV consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2005;43:167-176. |

| 13. | Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922-938. |

| 14. | Thai Guideline for the management of upper GI bleeding. Available from: URL: http://www.gastrothai.com/file/guideline%20Upper%20GI%20Bleeding.pdf. . |

| 15. | Lau JY, Leung WK, Wu JC, Chan FK, Wong VW, Chiu PW, Lee VW, Lee KK, Cheung FK, Siu P. Omeprazole before endoscopy in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1631-1640. |

| 16. | Dorward S, Sreedharan A, Leontiadis GI, Howden CW, Moayyedi P, Forman D. Proton pump inhibitor treatment initiated prior to endoscopic diagnosis in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;356:CD005415. |

| 17. | Corley DA, Stefan AM, Wolf M, Cook EF, Lee TH. Early indicators of prognosis in upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:336-340. |

| 18. | Elta GH. Approach to the patient with gross gastrointestinal bleeding. Textbook of gastroenterology. 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia 2003; 698-723. |

| 19. | Rockey DC. Sleisenger and Fordtrans gastrointestinal and liver disease. Philadelphia: Saunders 2006; 255-299. |

| 20. | Blatchford O, Murray WR, Blatchford M. A risk score to predict need for treatment for upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet. 2000;356:1318-1321. |

| 21. | Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut. 1996;38:316-321. |

| 22. | Saeed ZA, Ramirez FC, Hepps KS, Cole RA, Graham DY. Prospective validation of the Baylor bleeding score for predicting the likelihood of rebleeding after endoscopic hemostasis of peptic ulcers. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:561-565. |

| 23. | Hay JA, Lyubashevsky E, Elashoff J, Maldonado L, Weingarten SR, Ellrodt AG. Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage clinical--guideline determining the optimal hospital length of stay. Am J Med. 1996;100:313-322. |

| 24. | Aljebreen AM, Fallone CA, Barkun AN. Nasogastric aspirate predicts high-risk endoscopic lesions in patients with acute upper-GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:172-178. |

| 25. | Silverstein FE, Gilbert DA, Tedesco FJ, Buenger NK, Persing J. The national ASGE survey on upper gastrointestinal bleeding. II. Clinical prognostic factors. Gastrointest Endosc. 1981;27:80-93. |

| 26. | Forrest JA, Finlayson ND, Shearman DJ. Endoscopy in gastrointestinal bleeding. Lancet. 1974;2:394-397. |

| 27. | Almela P, Benages A, Peiro S, Anon R, Perez MM, Pena A, Pascual I, Mora F. A risk score system for identification of patients with upper-GI bleeding suitable for outpatient management. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:772-781. |

| 28. | Thong-Ngam D, Tangkijvanich P, Isarasena S, Kladchareon N, Kullavanijaya P. A risk scoring system to predict outcome of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding in Thai patients. J Med Assoc Thai. 1999;82:1234-1240. |

| 29. | Avgerinos A, Armonis A. Balloon tamponade technique and efficacy in variceal haemorrhage. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1994;207:11-16. |

| 30. | Tangmankongworakoon N, Rerknimitr R, Aekpongpaisit S, Kongkam P, Veskitkul P, Kullavanijaya P. Results of emergency gastroscopy for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding outside official hours at King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital. J Med Assoc Thai. 2003;86 Suppl 2:S465-S471. |

| 31. | del Olmo JA, Pena A, Serra MA, Wassel AH, Benages A, Rodrigo JM. Predictors of morbidity and mortality after the first episode of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2000;32:19-24. |

| 32. | Afessa B, Kubilis PS. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with hepatic cirrhosis: clinical course and mortality prediction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:484-489. |

| 33. | Lecleire S, Di Fiore F, Merle V, Herve S, Duhamel C, Rudelli A, Nousbaum JB, Amouretti M, Dupas JL, Gouerou H. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with liver cirrhosis and in noncirrhotic patients: epidemiology and predictive factors of mortality in a prospective multicenter population-based study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:321-327. |