Published online Feb 14, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.742

Revised: November 16, 2008

Accepted: November 23, 2008

Published online: February 14, 2009

AIM: To evaluate the diagnosis of chest pain with foregut symptoms in Chinese patients.

METHODS: Esophageal manometric studies, 24-h introesophageal pH monitoring and 24-h electrocardiograms (Holter electrocardiography) were performed in 61 patients with chest pain.

RESULTS: Thirty-nine patients were diagnosed with non-specific esophageal motility disorders (29 patients with abnormal gastroesophageal reflux and eight patients with myocardial ischemia). Five patients had diffuse spasm of the esophagus plus abnormal gastroesophageal reflux (two patients had concomitant myocardial ischemia), and one patient was diagnosed with nutcracker esophagus.

CONCLUSION: The esophageal manometric studies, 24-h intra-esophageal pH monitoring and Holter electrocardiography are significant for the differential diagnosis of chest pain, particularly in patients with foregut symptoms. In cases of esophageal motility disorders, pathological gastroesophageal reflux may be a major cause of chest pain with non-specific esophageal motility disorders. Spasm of the esophageal smooth muscle might affect the heart-coronary smooth muscle, leading to myocardial ischemia.

- Citation: Deng B, Wang RW, Jiang YG, Tan QY, Liao XL, Zhou JH, Zhao YP, Gong TQ, Ma Z. Diagnosis of chest pain with foregut symptoms in Chinese patients. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(6): 742-747

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i6/742.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.742

Recent reports[12] have indicated that recurrent chest pain is often a result of esophageal motility disorders or gastroesophageal reflux diseases (GERD), which is known as esophageal chest pain. Esophageal chest pain is very similar to symptoms seen during myocardial ischemia. It is also observed in patients with coronary artery disease with similar incidence (i.e. linked angina)[3]. As a result, differential diagnosis is often difficult and many patients with esophageal chest pain are misdiagnosed as having coronary artery disease[4]. Hence, the percentage of patients that are correctly treated and cured is relatively low. It is well known that esophageal manometry and 24-h intra-esophageal pH monitoring provide accurate diagnoses of esophageal motility disorders. As an incentive, Holter electrocardiography is more economical for these patients from developing countries compared to coronary artery opacification.

Previous reports have focused on the diagnosis of unclear chest pain via both coronary artery 24-h intra-esophageal pH monitoring and coronary artery opacification, which is very expensive to the patient, particularly in developing countries. In addition, very few studies have shown the efficacy of combined esophageal manometry, 24-h intra-esophageal pH monitoring, and electrocardiograms from Holter monitoring and the results have been inconclusive. Paterson et al[5] reported that there was no correlation between the incidence of chest pain and changes in esophageal manometry, 24-h intra-esophageal pH monitoring, and Holter electrocardiography. Wright et al[6] reported that physiologic gastroesophageal reflux does not induce electrocardiographic changes from Holter monitoring. However, Dobrzycki et al[7] and Patai et al[8] reported distinguishable alterations in 24-h intra-esophageal pH monitoring and Holter electrocardiography during chest pain. As a result, it was thought that simultaneous 24-h esophageal pH manometry and electrocardiograms from Holter monitoring could contribute to the diagnosis of atypical chest pain. However, up to now, many questions remain unaddressed. Can esophageal motility disorders affect myocardial ischemia? Can GERD affect myocardial ischemia? All of these diseases can cause chest pain, so it is unclear how to differentiate between cause and effect in these patients. Is there any clinical significance to the combination of these three types of monitoring in the differential diagnosis of unclear chest pain? Here, we present our experience in the combined application of monitoring over the past 6 years.

From September 2001 to May 2007, 61 Chinese patients with chest pain from the thoracic surgery department were enrolled into this study. The patients were both male (27) and female (34), ranging in age from 18 to 69 years (average age: 45.5 years). All patients had complaints of varying degrees of chest pain and most had symptoms of retrosternal pain or backache, ranging in duration from 60 d to 5 years (average duration of pain: 14.5 mo). Twenty patients had intermittent dysphagia and 40 had other symptoms such as regurgitation. There were no abnormalities in their hemogram, chest X-rays, routine electrocardiograms or esophago-gastroscopy.

Esophageal motility was studied by standard water perfusion and stationary manometry (Medtronic DPT-6000, Smith Medical, Sweden) with computer-assisted analysis (Polygram 2.0, Smith Medical, Sweden) of the tracings according to a previously published protocol[910]. Briefly, a station pull-through technique was applied, and measurements were made at the pressure levels of the lower esophageal sphincter (LESP), the relaxation rate of the lower esophageal sphincter (LESRR), the esophageal body, the upper esophageal sphincter and the pharynx.

Twenty-four-hour intra-esophageal pH was monitored using the classical DeMeester criteria[11]. A single channel, nasoesophageal, antimony pH-probe (Synectics Medical, Sweden) was positioned 5 cm above the lower esophageal sphincter and was connected to a portable data acquisition system (Digitrapper Mark II Gold, Synectics Medical, Sweden). Following 24-h intra-esophageal pH monitoring, chest leads at CM1, CM5 and CMF of a digital ambulatory 24-h Holter monitor (Life Card CF, Reynolds Medical, England) were positioned. Holter studies and 24-h pH monitoring were performed simultaneously. Following 24-h monitoring, data from the two monitors were analyzed by software (supplied by Life Card CF, Reynolds Medical, England and Digitrapper Mark II Gold, Synectics Medical, Sweden).

Esophageal contraction waves following swallowing were classified as (1) peristaltic, (2) simultaneous, (3) interrupted, or (4) dropped. Primary esophageal motility disorders were classified according to Chinese standards[12]: (1) Diffuse esophageal spasm; (2) Nutcracker esophagus; or (3) Non-specific esophageal motility disorders. Abnormal gastro-esophageal reflux was considered when the score was > 14.72. If the decreasing amplitude of the ST segment was above 0.1 mV, chest pain arousing from myocardial ischemia was considered, according to an electrocardiogram obtained from the Holter monitor.

In the present case report, 45 of 61 patients had different types of esophageal motility disorders (Table 1). The episodes of pain are shown in Table 1. Results of esophageal manometric studies and 24-h intra-esophageal pH monitoring are presented in Table 2.

| Diagnosis | Number cases and pain episodes | Cases combined with abnormal gastroesophageal reflux | Cases combined with myocardial ischemia | |||||

| Cases | Pain episodes | Cases | Pain episodes | Pain episodes with changes in 24-h pH monitoring | Cases | Pain episodes | Pain episodes with changes in Holter monitoring | |

| Non-specific esophageal motility disorders | 39 | 312 | 29 | 235 | 156 | 8 | 61 | 10 |

| Diffuse spasm of esophagus | 5 | 65 | 5 | 65 | 53 | 2 | 25 | 13 |

| Nutcracker esophagus | 1 | 18 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Normal case | 16 | 83 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Consolidation of table | 61 | 478 | 34 | 366 | 0 | 10 | 86 | 23 |

| Cases | LESP | LESRR | Overall length of LES | Abdominal length of LES | Swallow waves | pH monitoring DeMeester scores | |

| Non-specific esophageal motility disorders | 39 | Reduced in 29 patients (9.32 ± 1.53 mmHg) | Reduced in 28 patients (52.18 ± 20.51%) | Reduced in 21 patients (2.3 ± 0.1 cm) | Reduced in 18 patients (1.2 ± 0.1 cm) | 39 patients with simultaneous non- transmitted waves | 60.2 ± 12.4 |

| Diffuse spasm of esophagus | 5 | Normal in 5 patients (18.35 ± 2.92 mmHg) | Reduced in 5 patients (30.50% ± 6.65%) | Normal in 5 patients (3.3 ± 0.3 cm) | Normal in 5 patients (2.0 ± 0.1 cm) | 20% or more simultaneous contractions in response to wet swallows appearing in all five patients | 80.4 ± 35.5 |

| Nutcracker esophagus | 1 | 12.2 mmHg | 64.0% | 4.0 cm | 2.5 cm | High amplitude contracting wave appearing above 229.7 mmHg |

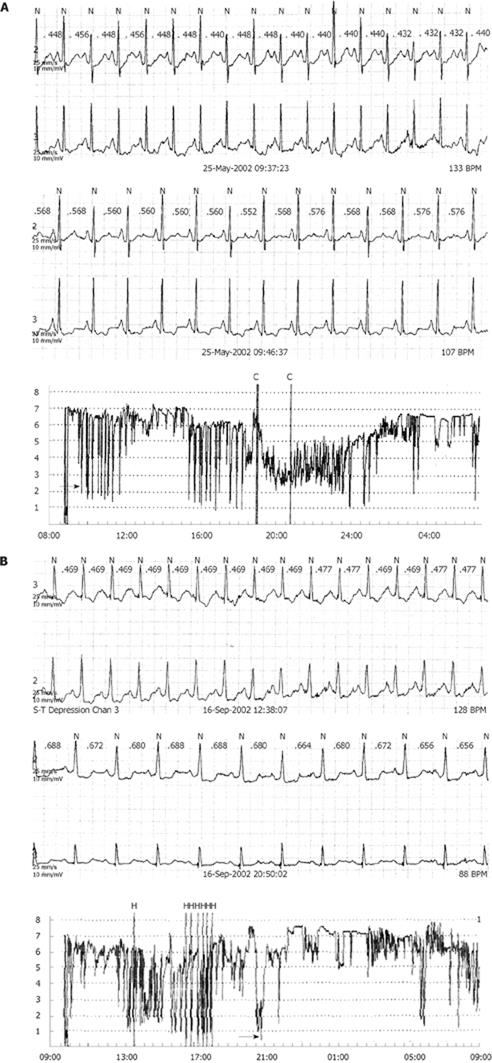

Eight patients were diagnosed with myocardial ischemia and non-specific esophageal motility disorders. Two patients were diagnosed with myocardial ischemia and diffuse spasm of the esophagus. Of the above 10 patients, eight had myocardial ischemia, which occurred with simultaneous abnormal gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) (Figure 1).

Recurrent chest pain is typically general and difficult to identify. Shrestha et al[4] reported that 30% of non-cardiac chest pain was caused by esophageal diseases such as GERD. Since the innervation and location of the esophageal nervous system in the body overlaps with the cardiac nervous system, symptoms are often similar. As a result, patients with esophageal chest pain are often misdiagnosed as having coronary artery disease[13]. Therefore, it is important for physicians to pay particular attention to the differential diagnosis of inconclusive esophageal chest pain.

As for the differential diagnosis of chest pain, there are very few studies investigating combined 24-h intra-esophageal pH and electrocardiograms from Holter monitoring. Several studies[56] have found that there is minimal correlation between the incidence of chest pain and changes in esophageal dysfunction and myocardial ischemia monitoring, while others have reported the opposite[78]. Therefore, in the present study, we reassessed the significance of the combined monitoring. In our study, 45 of 61 patients had esophageal disorders (the rate was 73.7%, which was rather high since the patients were recruited from the thoracic surgery outpatient clinic and some of them had pre-existing upper gastrointestinal symptoms such as dysphagia or regurgitation), and 10 (16.4%) patients had myocardial ischemia. We think that the main reason for the weak correlation between incidences of chest pain and changes in the combined monitoring reported by Paterson et al[5] and Wright et al[6] may be as follows: (1) the number of samples that were selected randomly was relatively small; and (2) there may have been an unknown heterogeneity of patient populations.

Esophageal motility disorders are the most common cause of esophageal chest pain[14]. Non-transmitted contraction waves appeared in all of the 39 patients with non-specific esophageal motility disorders, while 29 patients had abnormal gastroesophageal reflux. Among the total 235 pain episodes, 156 had changes in 24-h pH monitoring, indicating that abnormal gastroesophageal reflux may be the main cause of chest pain in these patients, confirmed by the observation by Patai et al[8] showing that proton pump inhibition with omeprazole alleviated gastroesophageal reflux as well as spontaneous chest pain. Interestingly, exercise potentiated the effect of intra-esophageal pH monitoring on electrocardiogram abnormalities (Badzynski et al[15]).

In the five patients with diffuse spasm of the esophagus, 20% or more had simultaneous contractions in response to wet swallows. However, some degree of peristaltic function was retained and the differential diagnosis could be made between diffuse spasm of the esophagus and achalasia. All of the five cases were defined as secondary diffuse spasm of the esophagus due to abnormal gastroesophageal reflux[13]. Two patients were diagnosed as having simultaneous diffuse spasm of the esophagus, myocardial ischemia, and GERD. We hereby hypothesize that diffuse spasm of the esophageal smooth muscle might affect spasm of the heart-coronary smooth muscle, leading to myocardial ischemia. All of these could be caused by a disturbance of the nervous system controlling the esophagus and cardiovascular system. It is interesting that this presumption is supported by Manfrini et al[16], in which esophageal spasm was considered to be related to myocardial ischemia (P < 0.05). Bidirectional analysis of causal effects showed that the influence between esophageal and coronary spasms was mutual and reciprocal in seven patients with variant angina. In two patients in our study, 25 pain episodes occurred with eight episodes causing changes in 24-h pH and Holter monitoring. This fact indicates that myocardial ischemia may occur with GERD, especially in patients with diffuse spasm of the esophagus.

Amplitude of the contractive wave in the patients with nutcracker esophagus was 229.7 mmHg, consistent with the diagnostic criteria[17].

Hence, combined monitoring of esophageal manometry, 24-h intra-esophageal pH and electrocardiograms from Holter monitoring are very significant for the diagnosis of recurrent chest pain, particularly for patients with foregut symptoms. We therefore, suggest that the diagnostic procedures of cloudy chest pain should be undertaken as follows. Firstly, the patients with cloudy chest pain should undergo routine examination including hemogram, chest X-rays, routine electrocardiogram and esophago-gastroscopy, in order to exclude severe diseases such as tumor or myocardial infarction. Secondly, the combined examinations should be recommended to the patients without the positive results of the routine examinations and with foregut symptoms as the “final step” in the diagnostic procedures. The detection rate is satisfactorily high, as shown in our cases. In conclusion, as an added incentive, the combined monitoring is very cost-effective for the patients, with a total cost of approximately 50 US dollars.

Studies on unclear chest pain are timely and important with the growing age of the world’s population. However, very few studies have been performed about esophageal manometric studies, 24-h intra-esophageal pH monitoring and a Holter electrocardiography for the differential diagnosis of chest pain caused by esophageal dysfunctional and/or myocardial ischemia. Interestingly, the results of published papers on the combined monitoring have been inconclusive.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the significance of combined monitoring in the diagnosis of chest pain with foregut symptoms in Chinese patients.

The study indicated that spasm of the esophageal smooth muscle might affect the heart-coronary smooth muscle, leading to myocardial ischemia. The combination of esophageal manometric studies, 24-h intra-esophageal pH monitoring and Holter electrocardiography are significant for the differential diagnosis of chest pain, particularly with foregut symptoms. As an added incentive, combined monitoring is very cost-effective for the patients, especially those from developing countries.

The manuscript describes an interesting study that aimed to demonstrate the etiology of chest pain. In fact, it is well known that non-cardiac chest pain is associated with GERD in about 50% of cases and that spastic esophageal motility disorders are related to chest pain. This study revisits the conflicting situation concerning the precise primary cause of chest pain, especially in patients in whom myocardial ischemia, GERD and esophageal spastic motility disorders are simultaneously found. As the authors pointed out, it has been suggested that spastic motility disorders may cause myocardial ischemia.

| 1. | Mudipalli RS, Remes-Troche JM, Andersen L, Rao SS. Functional chest pain: esophageal or overlapping functional disorder. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:264-269. |

| 2. | Rencoret G, Csendes A, Henríquez A. [Esophageal manometry in patients with non cardiac chest pain]. Rev Med Chil. 2006;134:291-298. |

| 3. | Fang J, Bjorkman D. A critical approach to noncardiac chest pain: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:958-968. |

| 5. | Paterson WG, Abdollah H, Beck IT, Da Costa LR. Ambulatory esophageal manometry, pH-metry, and Holter ECG monitoring in patients with atypical chest pain. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:795-802. |

| 6. | Wright RA, McClave SA, Petruska J. Does physiologic gastroesophageal reflux affect heart rate or rhythm? Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28:1021-1024. |

| 7. | Dobrzycki S, Baniukiewicz A, Korecki J, Bachórzewska-Gajewska H, Prokopczuk P, Musial WJ, Kamiński KA, Dabrowski A. Does gastro-esophageal reflux provoke the myocardial ischemia in patients with CAD? Int J Cardiol. 2005;104:67-72. |

| 8. | Patai A, Sipos E, Döbrönte Z. [Sinoatrial block caused by gastroesophageal reflux. The role of simultaneous 24 hr. esophageal pH-metry and Holter-ECG in the differential diagnosis of angina pectoris]. Orv Hetil. 1996;137:687-690. |

| 9. | Deng B, Wang RW, Jiang YG, Liao XL. The application of esophageal manometry and ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring test in the esophageal chest pain: 44 cases report. Zhonghua Xiongxin Xueguan Waike Zazhi. 2003;19:341-342. |

| 10. | Deng B, Wang RW, Jiang YG, Tan QY, Zhao YP, Zhou JH, Liao XL, Ma Z. Functional and menometric study of side-to-side stapled anastomosis and traditional hand-sewn anastomosis in cervical esophagogastrostomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;35:8-12. |

| 11. | DeMeester TR, Wang CI, Wernly JA, Pellegrini CA, Little AG, Klementschitsch P, Bermudez G, Johnson LF, Skinner DB. Technique, indications, and clinical use of 24 hour esophageal pH monitoring. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1980;79:656-670. |

| 12. | Deng B, Wang RW, Jiang YG, Ma Z, Liao XL. The significance of esophagealmotility testing and 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring in the diagnosis of chest pain. Zhongguo Xiongxin Xueguan Waike Linchuang Zazhi. 2004;11:262-264. |

| 13. | Szarka LA, DeVault KR, Murray JA. Diagnosing gastroesophageal reflux disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:97-101. |

| 14. | Kim SH, Lee JS, Im HH, Hwang KR, Jung IS, Hong SJ, Ryu CB, Kim JO, Jo JY, Lee MS. [The relationship between ineffective esophageal motility and gastro-esophageal reflux disease]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2005;46:255-261. |

| 15. | Budzynski J, Kłopocka M, Pulkowski G, Suppan K, Fabisiak J, Majer M, Swiatkowski M. The effect of double dose of omeprazole on the course of angina pectoris and treadmill stress test in patients with coronary artery disease--a randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled, crossover trial. Int J Cardiol. 2008;127:233-239. |

| 16. | Manfrini O, Bazzocchi G, Luati A, Borghi A, Monari P, Bugiardini R. Coronary spasm reflects inputs from adjacent esophageal system. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H2085-H2091. |

| 17. | Kamberoglou DK, Xirouchakis ES, Margetis NG, Delaporta EE, Zambeli EP, Doulgeroglou VG, Tzias VD. Correlation between esophageal contraction amplitude and lower esophageal sphincter pressure in patients with nutcracker esophagus. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:151-154. |