CASE REPORT

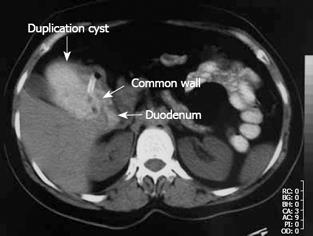

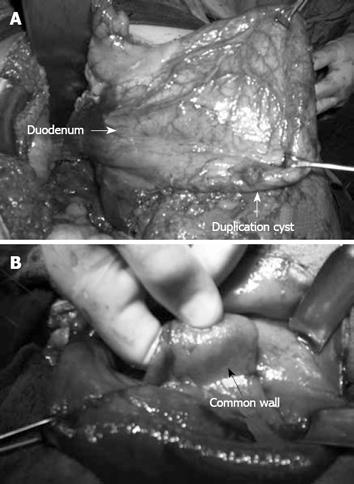

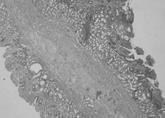

A 38-year-old woman who had occasional abdominal pain was referred to us with a clinical diagnosis of gastric outlet obstruction. The epigastrium was mildly sensitive on physical examination. Laboratory findings were normal but abdominal ultrasonography (US) showed gastric distension. Initial endoscopy was useless because of remnants of food. After nasogastric decompression, we repeated endoscopy but found no abnormalities. Upon abdominal computerized tomography (CT), a cystic lesion of 5 cm × 8 cm × 9 cm in diameter was observed, which extended along the lateral wall of the first and second parts of the duodenum. Remnants of food and orally taken contrast media were found within the lesion, and we observed the nasogastric tube entering the lesion through a defect between the duodenum and the cyst (Figure 1). We operated on the patient and found a cystic dilatation, 10 cm × 12 cm in diameter, anterolateral to the first and second parts of the duodenum (Figure 2A). We performed cystotomy and observed it make contact with the normally located duodenum at the posteromedial side of the cyst, through a defect of 2 cm × 2 cm in diameter. The wall between the duodenum and the cyst beneath the opening was covered with mucosa on both sides (Figure 2B). Thus, the diagnosis was cystic and communicating duodenal duplication. The wall between the cyst and duodenum was excised and the corners were sutured to form a cystoduodenostomy. The cystic wall is excised next to the pylorus above, duodenum laterally, pancreas medially and the third part of duodenum below, while the remnant is sutured primarily. The diagnosis was confirmed histopathologically by identifying a separate mucosa with its own muscularis mucosa on both sides of the wall between the cyst and duodenum and intervening connective tissue fibers (Figure 3). The patient was without complaint after 9 mo follow-up.

Figure 1 Oral and intravenous contrast-enhanced abdominal CT imaging.

The nasogastric tube was extended into the cyst, which was filled with oral contrast medium, through the defect between the duodenum and the cyst.

Figure 2 Operative view of cyst.

A: Duodenal duplication cyst; B: Inner surface of the cyst.

Figure 3 Common wall containing double mucosa with muscularis mucosa on each side and intervening connective tissue fibers (Hematoxylin and eosin, × 10).

DISCUSSION

Duplications of the gastrointestinal system can be observed anywhere along the alimentary tract, and they are located most often in the ileum and least often in the duodenum. Duodenal duplications can be cystic or tubular, communicating or non-communicating, but the most common type is cystic and non-communicating. These are generally located at the medial border of the first and second parts of the duodenum and extend to the anterior or posterior side[1–3]. Duodenal duplication observed in our case was cystic and located in the first and second parts of the duodenum, but it was of the communicating type and located on the antimesenteric side.

A variety of clinical manifestations have been reported that are determined by the type, site and size of the duplication. Generally, patients present with a palpable mass in the abdomen, signs of intestinal obstruction, or abdominal pain. Bleeding or perforation caused by peptic ulcer and jaundice, and pancreatitis caused by biliary obstruction may also be the manifestations[1–6]. In the current case, occasional attacks of abdominal pain and gastrointestinal obstruction were present. Obstruction in non-communicating cystic duplications is defined by compression of the duplication cyst, which is distended by intracystic secretions[1]. However, in our case, which was of the communicating type, it can be described by compression of the cyst, which was filled with the gastric contents but not drained.

Although radiological methods are helpful for diagnosis, preoperative diagnosis of duodenal duplication is rarely made accurately. In barium studies, in non-communicating cysts, the first and the second parts of the duodenum can be seen as compressed and displaced by a mass, whereas, in the communicating type, the cyst itself can be observed as being filled with barium[27]. In the current case, if barium studies had been performed, the communication between the duplication and duodenum would have been demonstrated better. Duodenal duplication is differentiated from other cystic lesions by the “gut signature” of its wall observed by abdominal or endoscopic US. Gut signature refers to the layered pattern of the wall, with the hyperechoic inner layer representing the submucosa and the hypoechoic outer layer representing the smooth muscle[8–10]. Peristalsis of the cyst wall noted upon real-time US is strongly suggestive of a duplication cyst[11]. US is an operator-dependent method and unfortunately it was not helpful in the diagnosis of our case. CT is valuable in identifying the type, location and the size of the duplication cyst. In the differential diagnosis of duodenal duplication, one should be mindful of choledochocele, pancreatic pseudocyst and intraluminal diverticulum[12]. In our case, the location of the cystic lesion and CT images made us think of cystic, communicating duodenal duplication. Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and gastroduodenoscopy are the other modalities that can be used for diagnosis, CT images were sufficient and MRI was not required in our case. Our not having a diagnostic sign upon endoscopy might have been caused by the fact that the endoscope we used was without lateral vision.

In spite of the diagnostic workup performed before the operation, accurate diagnosis of duodenal duplication is by histological examination. According to the analysis made by Merrot et al[1], two types of intra- or juxta-duodenal duplications occur: (1) a common wall formed by two separate mucosae with their own muscularis mucosa and a layer of intervening connective tissue; and (2) a common wall that comprises two mucosal layers with two smooth muscle layers, but that also contains biliary and pancreatic ducts. In our case, histological diagnosis of intraduodenal duplication was made by observation of the mucosa on both sides, each with its own muscularis mucosa, and connective tissue fibers between the two layers.

Management of duodenal duplications depends on the volume, type, location and proximity to the duodenal wall, pancreas or biliary ducts. If there is no communication between the mass and the biliary or pancreatic ducts, and if the vasculature allows, total resection is the procedure of choice. However, if it is not possible, partial resection or internal derivation must be carried out. In partial resection, all of the cyst wall is removed wherever possible, while the area of maximum adherence to the duodenum is preserved[113–15]. In our case, duplication was communicating and preservation of duodenal continuity would have been impossible if total resection had been performed. Thus, we performed partial resection with maximal removal of the cystic wall, which allowed secure closure. As the diameter of the communication was not efficient for adequate drainage of the cyst, the common wall between the cyst and the duodenum was excised and the corners were sutured to form a large cystoduodenostomy. This procedure is known as intraduodenally performed internal derivation, and it forms the basis of the endoscopic treatment of duodenal duplication[16].

In conclusion, duodenal duplication should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a patient who presents with abdominal symptoms when cystic structures neighboring the duodenum are demonstrated by radiology. Ideal treatment is total excision but, if not possible, subtotal excision and/or internal derivation should be performed.