Published online Dec 7, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5740

Revised: October 10, 2009

Accepted: October 17, 2009

Published online: December 7, 2009

AIM: To investigate the diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy (CE) in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB), and to determine whether the yield was affected by different bleeding status.

METHODS: Three hundred and nine consecutive patients (all with recent negative gastric and colonic endoscopy results) were investigated with CE; 49 cases with massive bleeding and 260 cases with chronic recurrent overt bleeding. Data regarding OGIB were obtained by retrospective chart review and review of an internal database of CE findings.

RESULTS: Visualization of the entire small intestine was achieved in 81.88% (253/309) of cases. Clinically positive findings occurred in 53.72% (166/309) of cases. The positivity of the massive bleeding group was slightly higher than that of the chronic recurrent overt bleeding group but there was no significant difference (59.18% vs 52.69%, P > 0.05) between the two groups. Small intestinal tumors were the most common finding in the entire cohort, these accounted for 30% of clinically significant lesions. In the chronic recurrent overt bleeding group angioectasia incidence reached more than 29%, while in the massive bleeding group, small intestinal tumors were the most common finding at an incidence of over 51%. Increasing patient age was associated with positive diagnostic yield of CE and the findings of OGIB were different according to age range. Four cases were compromised due to the capsule remaining in the stomach during the entire test, and another patient underwent emergency surgery for massive bleeding. Therefore, the complication rate was 1.3%.

CONCLUSION: In this study CE was proven to be a safe, comfortable, and effective procedure, with a high rate of accuracy for diagnosing OGIB.

- Citation: Zhang BL, Fang YH, Chen CX, Li YM, Xiang Z. Single-center experience of 309 consecutive patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(45): 5740-5745

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i45/5740.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.5740

Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) is defined as recurrent or persistent bleeding or iron deficiency anemia after a negative result from gastric and colonic endoscopy[1]. OGIB accounts for approximately 5% of all gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and lesions in the small bowel[2]. Previous capsule endoscopy (CE) investigations of small intestine showed the value in finding small intestinal diseases, especially inflammatory bowel disease and OGIB. CE is a tool that allows for visualization of mucosa throughout the entire small bowel and it has already gained widespread clinical acceptance. CE has been shown to be superior to push enteroscopy[3,4], small bowel follow-through[5] and computed tomography (CT) scan[6] in detecting bleeding lesions in the small intestine. Early reports indicated that 45%-66% of patients with OGIB were detected by CE[3,5,7]. Despite promising preliminary results, published studies were limited to small groups of patients. In this study a large group of OGIB patients were investigated by CE examination, including obscure-overt and a few obscure-occult patients. We divided these patients into a massive bleeding group (bloody stool or circulatory failure, serious anemia) and a chronic recurrent overt occult bleeding group (melena). Therefore, we investigated the outcome of CE in a large group of patients with OGIB from a single institution and determined whether the results of CE for OGIB patients were related to bleeding status. Also, the selection of OGIB candidates for successful CE evaluation was discussed in our study.

Three hundred and nine cases underwent CE for the indication of OGIB at our institution from May, 2003 to April, 2008. All patients suffering at least two episodes of bleeding prior to CE had undergone endoscopy without localization of a bleeding lesion. Data of the 309 cases were obtained by retrospective chart review. Data included: age, gender, inpatient or outpatient status, status of GI bleeding (massive bleeding vs chronic recurrent overt occult bleeding), median units of red blood cells (RBCs) transfused, mean hemoglobin value prior to endoscopic evaluation, prior radiographic evaluation, computed tomography (CT) evaluation, and lesion diagnosis confirmed by surgery. CE data collected included: whether the entire small intestine was visualized, CE findings in the small intestine and whether complications occurred. Pregnant women, patients with pace-makers or intestinal obstruction were excluded from the study. The study was approved by the local ethics committees.

The Given Diagnostic Imaging System (Yoqneam, Israel) was used in our study. This system is composed of three main subunits: an ingestible capsule endoscope, a data recorder, and a workstation. On the day before the examination, patients were allowed to be on a semi-liquid diet and received complete colonic irrigation (polyethylene glycol 4000, PEG4000) 12 h before the examination. Patients were deprived of water for 4 h and deformer (simethicone) was administered orally 30 min prior to the examination, respectively. Informed consent was obtained. Four hours after swallowing the capsules, subjects were allowed to take light snacks such as milk. During the examination, subjects were allowed to move freely but exposure to any strong electromagnetic field would be avoided. Eight hours later, data recorded would be downloaded to a RAPID workstation for graphic analysis. All capsules were for single use only.

Findings on CE were classified as diagnostic and non-diagnostic lesions. Examples of non-diagnostic lesions included red spots, white spots, erythema, scatter lymphangiectasia, active bleeding, blood clots, or small polyps. Examples of diagnostic lesions included angioectasias, tumors, or ulcers, obvious small bowel inflammation, and roundworms. A diagnostic lesion had to definitely or probably account for the patient’s bleeding and was diagnosed by two experienced endoscopists.

Statistical methods included χ2 analysis for comparison of the positive diagnostic yield of CE between patients with acute large bleeding and chronic recurrent overt occult GI bleeding. SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL) was used in our study, and P < 0.05 was considered a statistical significance.

The 309 cases with OGIB in this study are listed in Table 1 with regard to their baseline characteristics. Prior to CE, for all patients, the cause of OGIB could not be identified with either gastroscopy or colonoscopy. Among them, 39.16% (121/309) underwent a CT scan to detect the source of GI bleeding at the same time, and the percentage of patients who finally underwent surgical operation was 11% (34/309).

| Item | All (n = 309) | Massive bleeding (n = 49) | Chronic recurrent overt bleeding (n = 260) |

| Mean age ± SD (yr) | 55.5 ± 16.6 | 52 ± 19.1 | 56.1 ± 16.1 |

| Years (range, yr) | 13-87 | 13-87 | 15-86 |

| Gender n (%) | 150 M (48.5) | 27 M (55.1) | 123 M (47.3) |

| 159 F (51.5) | 22 F (44.9) | 137 F (52.7) | |

| Patient status (n) | |||

| Outpatient | 141 | 0 | 141 |

| Inpatient | 168 | 49 | 119 |

| Median units of RBCs transfused (U/mL) | 4.63 ± 4.23 | 8.00 ± 6.46 | 4.00 ± 6.85 |

| Mean Hb value (range, g/dL) | 8.73 (4.52-12.10) | 6.20 (4.52-9.85) | 9.21 (6.56-12.10) |

Completion of CE: Of all CE procedures performed, 81.88% (253/309) extended through the entire small intestine. However, the rate of going right through the intestine in the chronic recurrent overt bleeding group was higher than that of the massive bleeding group (83.85% vs 69.39%, P = 0.017, respectively). Four cases with gastric motility disorder resulting in the capsule remaining in the stomach during the entire test were compromised, and another case resulted in emergency surgery because of the large amount of bleeding.

The diagnostic ability of CE: The yield of CE, defined as diagnostic lesions as the source of OGIB, was 53.72% (166/309) in the entire cohort and slightly higher in those patients with massive bleeding compared to those in the chronic recurrent overt bleeding group, with no significant statistical difference between groups (59.18% vs 52.69%, P > 0.05, respectively) (Table 2).

| All (n = 309) | Massive bleeding (n = 49) | Chronic recurrent overt bleeding (n = 260) | |

| Diagnostic | 166 (53.7) | 29 (59.2) | 137 (52.7) |

| Non-diagnostic/negative | 143 (46.3) | 20 (40.8) | 123 (47.3) |

Small bowel angioectasias and small bowel tumors (masses) were common and accounted for over 28% of lesions in the entire cohort (Table 3). In the chronic recurrent overt bleeding group, angioectasia incidence was over 29% (Table 3), while in the massive bleeding group small bowel tumors were a common finding at over 51%. Angioectasias were the second most common lesion and accounted for 22.2%, while Crohn’s disease was in third place (Table 3).

| Type of lesion | All | Massive bleeding | Chronic recurrent overt bleeding |

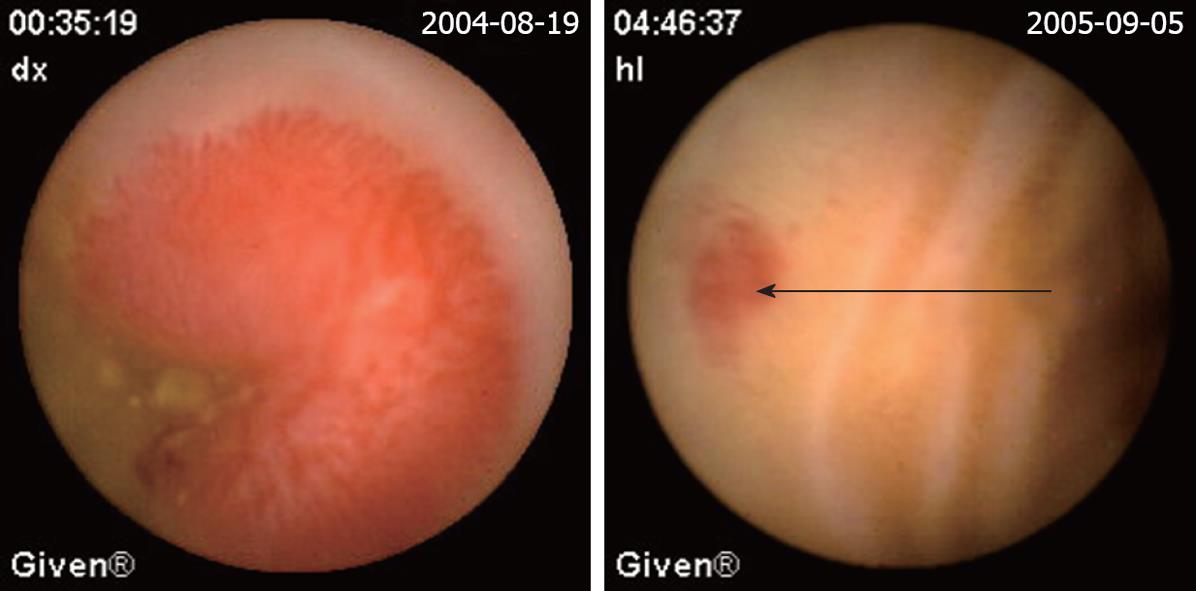

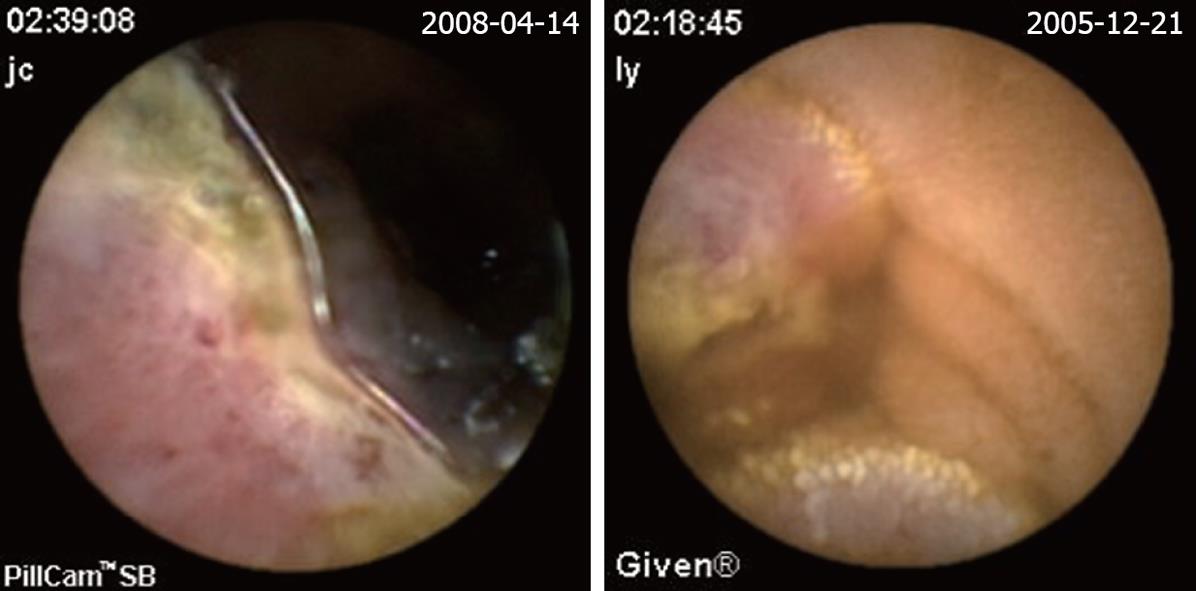

| Angioectasias (Figure 2) | 49 (28.3) | 6 (22.2) | 43 (29.9) |

| SB tumor | 53 (30.6) | 15 (51.7) | 38 (26.0) |

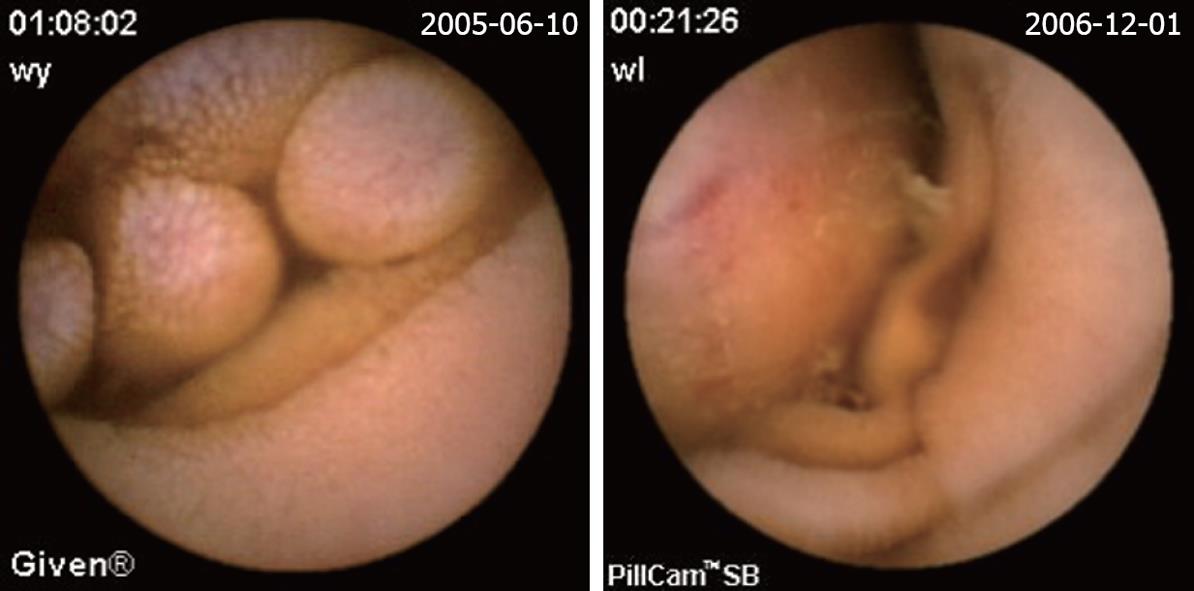

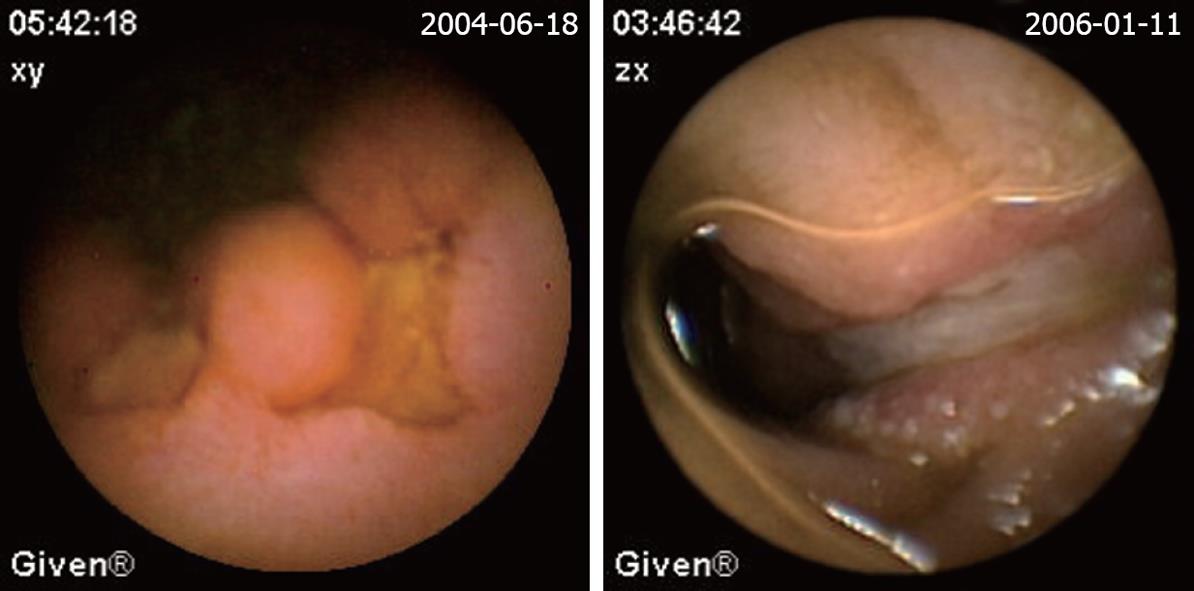

| Mesenchymoma (Figure 3) | 15 (8.7) | 5 (17.2) | 10 (6.9) |

| Polyps | 13 (7.5) | 2 (6.9) | 11 (7.6) |

| Hemangioma (Figure 4) | 6 (3.5) | 2 (6.9) | 4 (2.8) |

| Lipoma | 4 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 4 (2.8) |

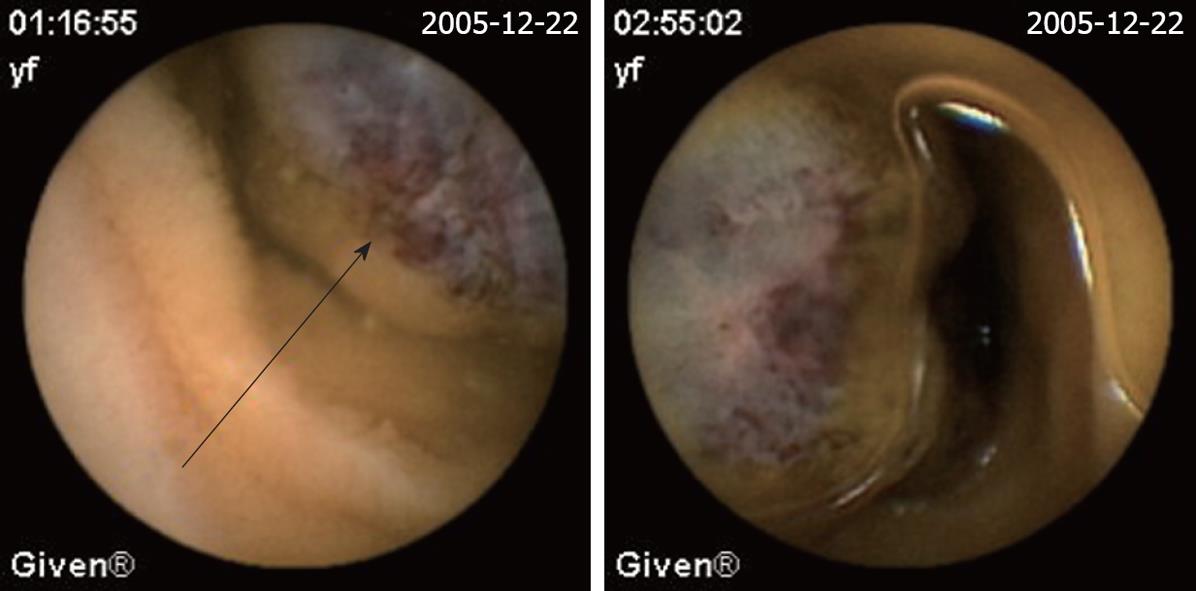

| Lymphoma (Figure 5) | 4 (2.3) | 2 (6.9) | 2 (1.4) |

| BRBNS | 2 (1.2) | 2 (6.9) | 0 (0) |

| Adenoma | 1 (0.6) | 1 (3.5) | 0 (0) |

| Metastatic melanoma | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) |

| Mass | 7 (4.0) | 1 (3.5) | 6 (4.2) |

| Crohn’s disease (Figure 6) | 25 (14.5) | 2 (6.9) | 23 (16.0) |

| Ulcer | 15 (8.7) | 2 (6.9) | 13 (9.0) |

| Multiple ulcer | 11 (6.4) | 1 (3.5) | 10 (7.6) |

| Isolated ulcer | 4 (2.3) | 1 (3.5) | 3 (2.1) |

| SB verminosis | 12 (6.9) | 2 (6.9) | 10 (6.9) |

| Non-specific enteritis | 10 (5.8) | 0 (0) | 10 (6.9) |

| SB diverticulum | 7 (4.0) | 1 (3.5) | 6 (4.2) |

| SAME | 1 (0.6) | 1 (3.5) | 0 (0) |

| Portal hypertension SB disease | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) |

| Total | 173 | 29 | 144 |

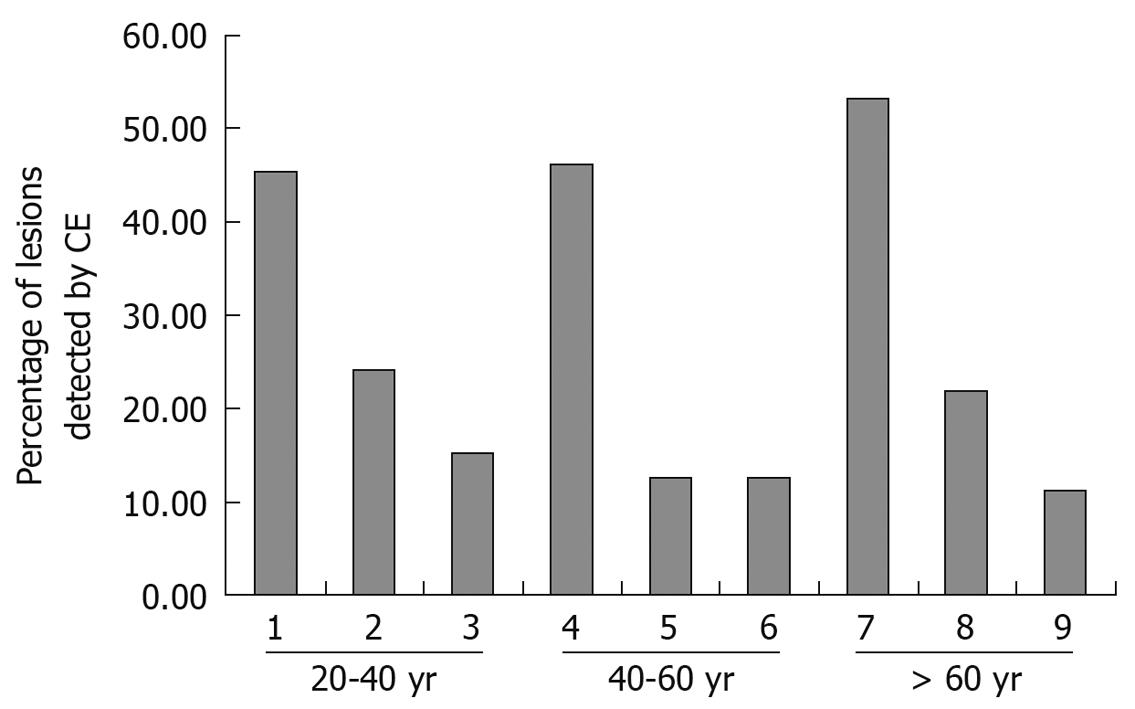

Age and diagnostic yield of CE: Increasing patient age was associated with positive diagnostic yield of CE and the findings of OGIB were different according to age range. In the 20-40 years age group, Crohn’s disease was found in almost 45.5% (15/33) of cases, and in the 40-60 years age group, tumor incidence was 46.2% (26/56). Angioectasias occurred in over 50% (39/73) of cases when the patients’ age was over 60 years (Figure 1).

Failed diagnoses of CE: Among the non-diagnostic studies, 15 cases were diagnosed by further examinations, such as CT scan, angiography, and surgery. In the massive bleeding group, two cases were negative and three cases were actively bleeding with unavailable diagnostic lesions. In the chronic recurrent overt bleeding group, four cases were actively bleeding but without diagnostic lesions. One case was diagnosed as tumor but finally confirmed as Meckel’s diverticulum by surgical operation. One case was diagnosed by CE as ulcer and was confirmed as tumor by surgical operation. Four cases were negative.

OGIB is the main indicator of the appropriateness of CE as a diagnostic procedure. Many studies have demonstrated a high degree of usefulness of CE as a diagnostic method. The common findings of OGIB reported are angioectasias, small bowel tumor or mass, inflammation, Meckel’s diverticulum, etc. Barium small bowel examination, angiography and push enteroscopy were the common evaluations for OGIB before the development of CE. Barium showed a diagnostic rate of 3%. Angiography was an invasive method, with a diagnostic rate of 27%-77%, requiring a blood flow > 0.5 mL/min, while push enteroscopy could not reach the lower part of the small bowel and had a diagnostic rate of 19%-32%. Recently, double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) has been introduced for the diagnosis of OGIB, as reported by a meta analysis[8]. The diagnostic yield from CE was significantly higher than that of DBE without the combination of oral and anal insertion approaches [137/219 vs 110/219, OR 1.67 (95% CI: 1.14-2.44), P < 0.01, respectively], but not superior to the yield of DBE with combination of those two insertion approaches [26/48 vs 37/48, OR 0.33 (95% CI: 0.05-2.21), P > 0.05), respectively]. However, the DBE is invasive and patients are not as tolerant of this method. CE is the only non-invasive method which can examine the whole small intestine.

All cases in our study could tolerate well the CE examination. Five cases were compromised, one in the chronic recurrent overt bleeding group because of capsule retained in the stomach, and four in the massive bleeding group. Among these four cases, three were compromised because of somatostatin; the capsules were all retained in the stomach due to disorders of gastric mobility. In one Crohn’s patient CE was obstructed. No other complication occurred. Therefore, the complication rate was 1.3%. Technical problems and complications of CE are infrequent. Former studies showed a rate of CE complications ranging from 0.75%-5%[9-11] and also that the existence of patients who had difficulty swallowing the capsule was a rare event. In patients with known altered gastric mobility, the problem could be easily solved by endoscopic placement of the capsule into the duodenum[12,13].

In our study, CE progressed through the whole small bowel in 81.55% (253/309) of patients, and complete progression rate in the chronic recurrent overt bleeding group was higher than that of the massive bleeding group. CE did not reach the ileocecum because of retention in the intestine due to motility disorder or stricture of the intestinal lumen. Capsule retention occurred almost universally at the site of lesions. In these patients, surgical intervention to retrieve the trapped capsule also allowed for resection of the small bowel involved in the lesion. CE retention by the lesions in our study was found in small bowel Crohn’s disease cases and small bowel tumors.

The bowel preparation with PEG and simethicone ensured a good quality of pictures. The 309 patient cohort in our study is the largest series in published studies. The diagnostic rate in our study was 53.72%, which was similar to previous published studies. The diagnostic accuracy yield of CE in published reports ranges from a rate of 30% to 92%, mainly depending on the definition of positive findings and the status of bleeding investigated[3,5,9,14-16]. The yield in a series of 260 patients previously reported was 53%. In patients with ongoing obscure overt GI bleeding the yield was 87%, and 46% in patients with obscure occult bleeding[11]. In this present study we included the presence of active blood as a positive finding. We discovered that the diagnostic rates in both the massive bleeding group and the chronic recurrent overt bleeding group were not statistically significantly different; 59.18% (29/49) and 52.69% (137/260), respectively. These results demonstrate that CE is the first diagnostic option for patients with massive bleeding, since the diagnostic rate was not affected by blood in the small bowel lumen. The relationship between the timing of the procedure and the diagnostic yield of CE remains a controversial issue. Pennazio et al[9] found the highest yield in patients with ongoing GI bleeding, and therefore argued for ordering a CE procedure earlier in the setting of obscure overt bleeding. One would presume that blood in the GI tract would mask visualization of the mucosa and that lesions could easily be missed. Delaying CE until after an acute bleed may allow for clearance of residual blood and better visualization of the mucosa and suspicious lesions. However, our study demonstrated that acute large bleeding did not affect the diagnostic rate.

The definition of a positive finding on CE is an important idea not addressed in early reports[17]. Although experts have begun to address this issue, final consensus has not yet been reached[17-19]. For the purposes of this study, nonspecific mucosal changes such as red spots, erythema, scatter lymphangiectasia and thickened folds were considered to be clinically insignificant. Lesions such as angioectasias, tumors, masses or ulcers were included as positive findings in this series if they could completely or partially account for the GI bleeding. In our study, active bleeding but without definite lesion was described as a non-diagnostic finding. Figures 2,3,4,5,6 show the typical lesions found in our study.

There were 15 cases confirmed as being a pseudo-negative result surgically. Five were in the massive bleeding group; 2 of these on CE were negative, and 3 of them found only active bleeding but without diagnostic lesions. Ten cases were in the massive bleeding group, 4 of them on CE were negative, and 4 of them found only active bleeding but without diagnostic lesions. One case was diagnosed as tumor but finally confirmed as Meckel’s diverticulum by surgery, while another case indicating an ulcer was confirmed as small tumor by surgery.

CE can completely cover the whole GI tract and the procedure is well tolerated. It may provide false-positive and false-negative findings due to the possibility of uncontrollable movement and low-resolution pictures taken[20]. It was recently reported that CE missed an advanced small intestinal cancer that was later diagnosed with push enteroscopy[21], suggesting that CE is not an exclusive procedure but one complementary to other diagnostic tools in the assessment of small intestinal lesions. In Mehdizadeh’s series[22], CE found a potential bleeding source in 63 patients, but 34.9% (22/63) of them received negative results in the following DBE procedure. In our study, failed or negative findings of CE may have resulted from four main reasons: (1) growth pattern of lesions: transmural and extra-mural lesions could not be detected by CE; some angioectasias could only be detected by microscope; (2) technical factors of CE: the visual field of CE was only 140°, which perhaps leads to a blind spot; some lesions could be omitted due to movement of CE which could not be controlled. One case with Mechel’s diverticulum was diagnosed as small bowel tumor because of only partial views of the lesion; (3) cleanness of small bowel: in our study all cases were prepared with PEG and simethicone prior to examination and the visualization of CE was better than without any preparation, but in some cases, bubbles and food debris still affected the visualization. Delay of gastric motility caused by disease or drugs such as somatostatin would retain the capsule in the stomach, which could not go through the whole small bowel during the working time. The large number of false positives may result from the definition of clinically significant vs clinically insignificant findings.

In this study, common findings of lesions with OGIB were small bowel tumor (mass), angioectasias and Crohn’s disease. In the massive bleeding group, common findings of OGIB were small bowel tumor or mass and angioectasias, while in the chronic recurrent overt bleeding group common findings of OGIB were angioectasias, small bowel tumor (mass), and Crohn’s disease. A higher positive percentage of small intestine tumors was found compared with all previous studies published due to the definition of diagnostic lesion. Some of the angioectasias discovered in our study cannot be assumed to contribute to the bleeding, and these cases were not included in the positive findings.

In this study, younger patients were more often found to have Crohn’s disease, and older patients (older than 60 years) were prone to have angioectasias, while between 40 and 60 years, tumors accounted for a bigger proportion. According to the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA)[23], younger patients are likely to have small intestinal tumors, Meckel’s diverticulum, Dieulafoy’s lesion, and Crohn’s disease, while older patients (older than 40 years) are prone to bleeding from vascular lesions, which comprise of up to 40% of all causes, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced small bowel disease. Our finding was somewhat different from the AGA. Thus, in clinical work, patients who are suspected of having Crohn’s disease should be examined by CE as early as possible.

In summary, tolerance of administration, higher diagnostic yield, improvement in patient outcome and lower complication rate make CE an important advance in the diagnosis of OGIB. The AGA strongly recommended the CE as the first choice for OGIB. In our large cohort undergoing clinical investigation, we demonstrate that diagnostic rate of OGIB is determined by the definition of a clinically significant lesion. In addition, the massive bleeding status did not affect the positive detection rate.

Capsule endoscopy (CE) is a tool for visualization of mucosa throughout the entire small bowel. It has already gained a wide clinical acceptance in the evaluation of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB). Despite promising preliminary results, published studies were limited to small groups of patients with heterogeneous indications.

CE is now commonly performed for gastrointestinal bleeding of obscure origin. However, reports about large groups of patients with OGIB receiving CE are rare in the literature up till now.

Published studies of CE in the diagnosis of OGIB were limited to small groups of patients. The study analyzed a large group of OGIB patients, so the finding will be more objective. The authors concluded that the clinically important findings by CE in patients with OGIB were not affected by the different bleeding status, but disease diagnosis by CE is related to different bleeding status and ages. Small bowel tumor was the most common finding in general and also in the massive bleeding group. Angioectasias accounted for the majority of cases in the chronic recurrent overt bleeding group.

CE is now widely used to diagnose small bowel diseases, especially in patients with OGIB. More and more patients who are suspected of having small bowel diseases are diagnosed using CE with less discomfort, less time taken and also fewer financial costs.

CE is a device that can be easily swallowed by patients. It can progress through the whole digestive tract and take two photos every second. These photos can be studied on a workstation.

The study is well constructed. It is a retrospective review of all the OBIG cases from a single referral centre and is, admittedly, one of the biggest series of its kind. Other than that though, it simply confirms findings of previous reports in the field.

Peer reviewer: Anastasios Koulaouzidis, MD, MRCP (UK), Day Case & Endoscopy Unit, Centre of Liver and Digestive Disorders, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh,51 Little France Crescent, Edinburgh, EH16 4SA, Scotland, United Kingdom

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: evaluation and management of occult and obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:197-201. |

| 2. | Lewis BS. Small intestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1994;23:67-91. |

| 3. | Ell C, Remke S, May A, Helou L, Henrich R, Mayer G. The first prospective controlled trial comparing wireless capsule endoscopy with push enteroscopy in chronic gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2002;34:685-689. |

| 4. | Lim RM, O’Loughlin CJ, Barkin JS. Comparison of wireless capsule endoscopy (M2A™) with push enteroscopy in the evaluation of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:S83. |

| 5. | Costamagna G, Shah SK, Riccioni ME, Foschia F, Mutignani M, Perri V, Vecchioli A, Brizi MG, Picciocchi A, Marano P. A prospective trial comparing small bowel radiographs and video capsule endoscopy for suspected small bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:999-1005. |

| 6. | Hara AK, Leighton JA, Sharma VK, Fleischer DE. Small bowel: preliminary comparison of capsule endoscopy with barium study and CT. Radiology. 2004;230:260-265. |

| 7. | Lewis BS, Swain P. Capsule endoscopy in the evaluation of patients with suspected small intestinal bleeding: Results of a pilot study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:349-353. |

| 8. | Chen X, Ran ZH, Tong JL. A meta-analysis of the yield of capsule endoscopy compared to double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with small bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4372-4378. |

| 9. | Pennazio M, Santucci R, Rondonotti E, Abbiati C, Beccari G, Rossini FP, De Franchis R. Outcome of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after capsule endoscopy: report of 100 consecutive cases. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:643-653. |

| 10. | Barkin JS, Friedman S. Wireless capsule endoscopy requiring surgical intervention: the world’s experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:S298. |

| 11. | Carey EJ, Leighton JA, Heigh RI, Shiff AD, Sharma VK, Post JK, Fleischer DE. A single-center experience of 260 consecutive patients undergoing capsule endoscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:89-95. |

| 12. | Carey EJ, Heigh RI, Fleischer DE. Endoscopic capsule endoscope delivery for patients with dysphagia, anatomical abnormalities, or gastroparesis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:423-426. |

| 13. | Hollerbach S, Kraus K, Willert J, Schulmann K, Schmiegel W. Endoscopically assisted video capsule endoscopy of the small bowel in patients with functional gastric outlet obstruction. Endoscopy. 2003;35:226-229. |

| 14. | Chong AK, Taylor AC, Miller AM, Desmond PV. Initial experience with capsule endoscopy at a major referral hospital. Med J Aust. 2003;178:537-540. |

| 15. | Adler DG, Knipschield M, Gostout C. A prospective comparison of capsule endoscopy and push enteroscopy in patients with GI bleeding of obscure origin. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:492-498. |

| 16. | Scapa E, Jacob H, Lewkowicz S, Migdal M, Gat D, Gluckhovski A, Gutmann N, Fireman Z. Initial experience of wireless-capsule endoscopy for evaluating occult gastrointestinal bleeding and suspected small bowel pathology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2776-2779. |

| 18. | Cave DR. Reading wireless video capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2004;14:17-24. |

| 19. | Fireman Z. The light from the beginning to the end of the tunnel. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:914-916. |

| 20. | Gerson LB, Van Dam J. Wireless capsule endoscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy for the diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;7:130-135. |

| 21. | Madisch A, Schimming W, Kinzel F, Schneider R, Aust D, Ockert DM, Laniado M, Ehninger G, Miehlke S. Locally advanced small-bowel adenocarcinoma missed primarily by capsule endoscopy but diagnosed by push enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2003;35:861-864. |

| 22. | Mehdizadeh S, Ross AS, Leighton J, Kamal A, Chen A, Schembre D, Binmoeller K, Kozarek R, Waxman I, Gerson L. Double balloon enteroscopy (DBE) compared to capsule endoscopy (CE) among patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB): a multicenter U.S. experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:AB90. |

| 23. | Raju GS, Gerson L, Das A, Lewis B. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute medical position statement on obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1694-1696. |