Published online Dec 7, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5700

Revised: October 17, 2009

Accepted: October 24, 2009

Published online: December 7, 2009

AIM: To assess the management and outcome of nonerosive gastro-esophageal reflux disease (NERD) patients who were identified retrospectively, after a 5-year follow-up.

METHODS: We included patients with gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms who had a negative endoscopy result and pathological 24-h esophageal pH-monitoring while off therapy. We interviewed them after an average period of 5 years (range 3.5-7 years) by means of a structured questionnaire to assess presence of GERD symptoms, related therapy, updated endoscopic data and other features. We assessed predictors of esophagitis development by means of univariate and multivariate statistical analysis.

RESULTS: 260 patients (137 women) were included. Predominant GERD symptoms were heartburn and regurgitation in 103/260 (40%). 70% received a maintenance treatment, which was proton pump inhibitor (PPI) in 55% of cases. An average number of 1.5 symptomatic relapses per patient/year of follow-up were observed. A progression to erosive gastro-esophageal reflux disease (ERD) was found in 58/193 (30.0%) of patients undergoing repeat endoscopy; 72% of these were Los Angeles grade A-B.

CONCLUSION: This study shows that progression to ERD occurs in about 5% of NERD cases per year, despite therapy. Only two factors consistently and independently influence progression: smoking and absence of PPI therapy.

- Citation: Pace F, Pallotta S, Manes G, de Leone A, Zentilin P, Russo L, Savarino V, Neri M, Grossi E, Cuomo R. Outcome of nonerosive gastro-esophageal reflux disease patients with pathological acid exposure. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(45): 5700-5705

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i45/5700.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.5700

Evaluating the natural history of gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) is useful for a number of reasons, as this knowledge may help to: (1) discern the percentage of the population that will progress from non-erosive to erosive disease with its complications, such as stricture, Barrett’s oesophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma, or from exclusively esophageal to extraesophageal manifestations; (2) define, assess and validate predictivity of risk factors for such disease complications; (3) determine if medical, surgical or endoscopic therapies are able to positively modify the natural course of the disease; and (4) determine the need for maintenance therapy to prevent complications and persistent symptoms.

Others[1,2] have pointed out that many factors make it difficult to study the natural history of GERD, notably the evolving definition of the disease and the lack of a diagnostic standard. As a consequence, few studies in the literature have addressed the issue of defining the natural history of erosive GERD, and even less that of nonerosive gastro-esophageal reflux disease (NERD) or extraesophageal GERD and complications.

Until recently, patients with endoscopic-negative reflux disease were considered to suffer from a milder disease[3], i.e. requiring less intensive/prolonged treatment and possibly characterized by a better long-term prognosis. This concept was subsequently proven to be incorrect; as an example, the impairment in disease-related quality of life appears to be similar in GERD patients with or without endoscopic esophagitis and is related in both instances to symptom severity[4]. Also, the symptomatic acute response to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) drugs in patients with or without endoscopic mucosal damage may be worse in NERD[5,6]. Finally, after discontinuation of acute treatment, symptomatic relapse within 6 mo appears to affect a similarly high proportion of both GERD groups[7].

Up till now, however, it has not been entirely clear whether and in what proportion GERD patients with symptomatic syndrome but without mucosal damage[8] may progress to disease with mucosal damage.

The aim of this study was to assess the outcome of NERD patients with pathological acid reflux at entry after a 5-year follow-up, in three Italian tertiary care centres. Additionally, we investigated which factors are related to development of esophagitis.

We retrospectively identified all patients referred to our outpatient departments during the period 1996-2003 for investigation of gastroesophageal (GER) disease symptoms. Subjects were included in the study provided that (1) they were off PPI therapy for at least the preceding 7 d, (2) had a negative upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy, (3) had a 24-h esophageal pH-monitoring result showing pathological GER, i.e. a 24-h esophageal acid exposure greater than 4.4%, corresponding to the 95th percentile of normal Italian subjects and (4) were able to accept a telephone interview[9]. We interviewed the subjects after an average period of 5 years (range 3.5-7 years) by means of a structured questionnaire, already used in a previous study[10], to assess presence and type of GERD symptoms (i.e. typical: heartburn or regurgitation, and atypical, i.e. chronic cough, pharyngodynia, hoarseness, chest pain), antireflux drug therapy (presence and type), updated endoscopic data and other features regarding their present clinical status. The questionnaire allowed the patient to identify the most bothersome GERD symptom, be it typical or atypical, as the predominant one. Collected data at study entry included demographic characteristics, such as age, gender and body mass index (BMI), the reason for undergoing the examination, pattern of GERD symptoms (Table 1), and the results of index upper GI endoscopy and 24-h esophageal pH-metry. Both investigations were carried out while off PPI therapy.

| M/F | 121/139 |

| Age ( yr) | 49.5 ± 14 |

| BMI | 25.24 ± 3.7 |

| EAE (%) | |

| 24 h | 6.8 ± 5.4 |

| Upright | 5.6 ± 6.6 |

| Supine | 6.8 ± 7.6 |

| No. of smokers | 132 |

| Patients with predominant typical symptoms | 103 (39.6%) |

| Patients with predominant atypical symptoms | 142 (54.6%) |

| Patients with both typical & atypical predominant symptoms | 15 (5.7%) |

Descriptive statistics consisted of t tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. We conducted a univariate logistic regression to evaluate the influence of each risk factor, such as gender, age, BMI, smoking, typical and atypical symptoms, use of therapy, pH-monitoring reflux parameters, on the dependent variable, i.e. development of esophagitis. Significant prognostic factors were then subjected to a multivariate analysis with logistic regression to evaluate the association among the determinants while simultaneously controlling for the effect of other variables. We controlled for several covariates, and only variables with P > 0.1 were kept in the model. Statistical significance was defined by a two-sided alpha level of 0.05. A Cox model was ultimately used to construct the survival curves.

All analyses were performed using statistical software (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

We were able to identify 995 patients overall who were referred for GERD symptoms. 260 patients (137 women) satisfied the inclusion criteria and were included in the study. Mean age at the time of initial evaluation was 50 ± 14 (SD) years, with a BMI of 25.24 ± 3.72; 50% were smokers. The clinical and demographic characteristics of patients are listed in Table 1.

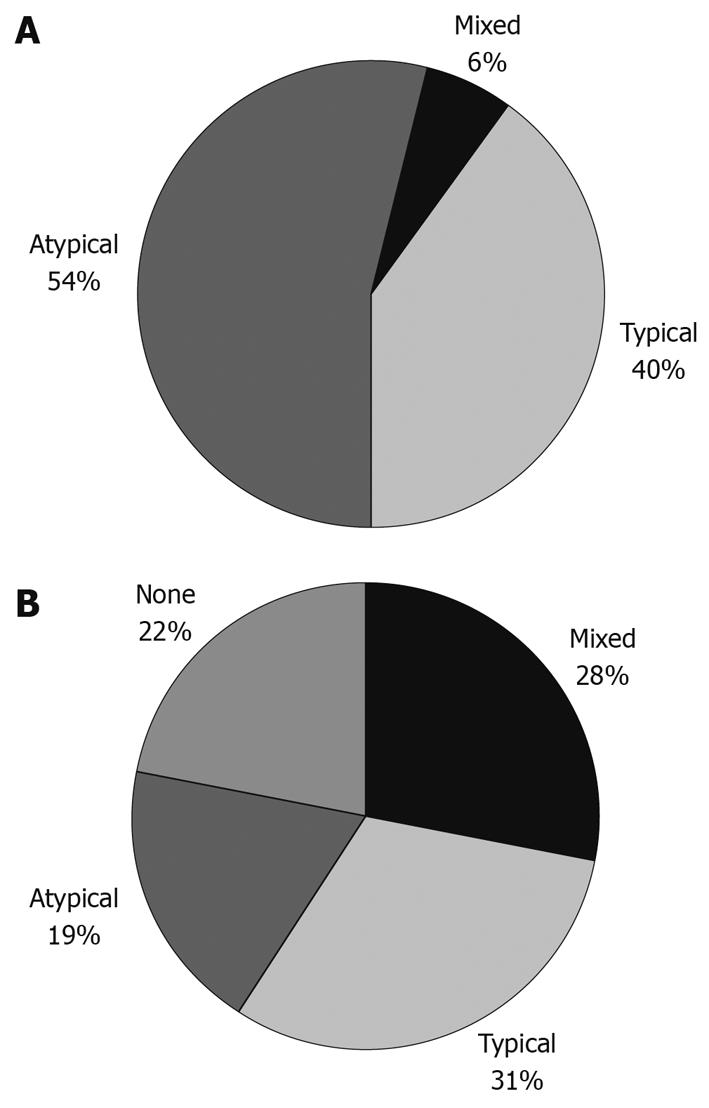

Predominant GERD symptoms were typical in 103/260 (40%), atypical in 142/260 (54%) and mixed, i.e. similarly dominating the clinical picture, in the remaining 15/260 (6%) (Figure 1A). The mean percentage time with pH < 4 was 7.1% ± 2.6%. At interview, after a median follow-up time of 5 years, typical symptoms such as heartburn and regurgitation were still present in 80 patients (31%). The distribution of symptoms at follow-up is presented in Figure 1B.

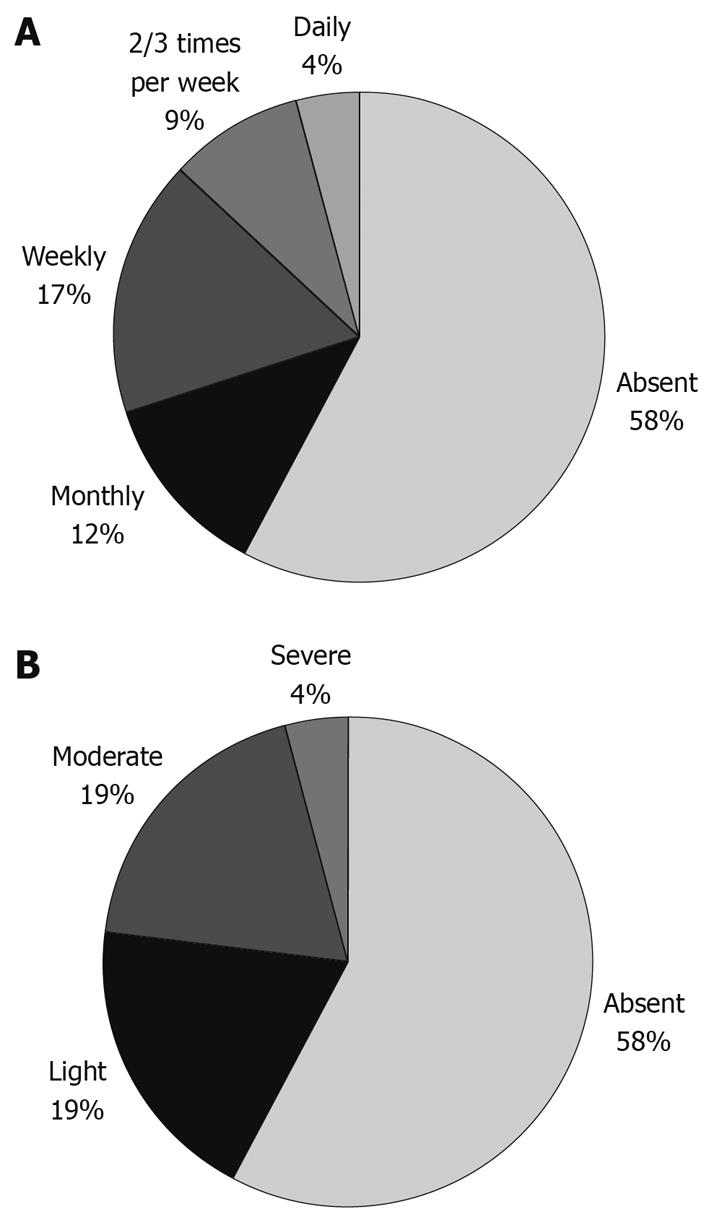

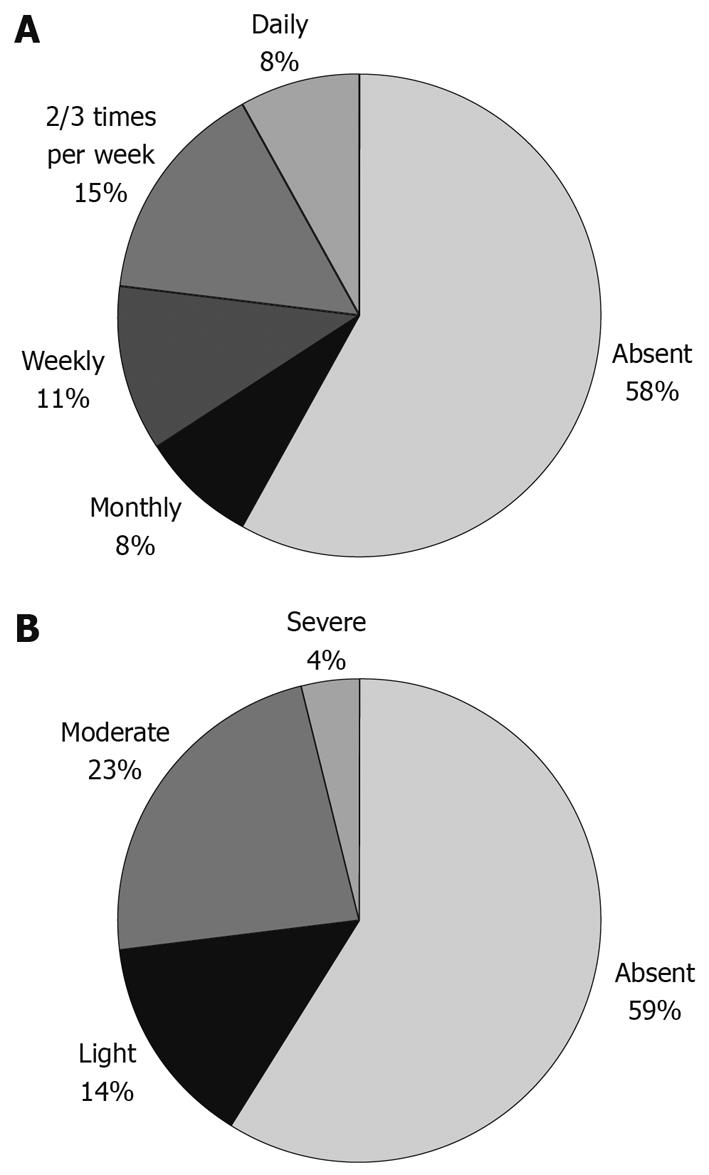

Frequency and severity of heartburn and regurgitation at follow-up are presented in Figures 2 and 3, respectively. Most patients had received a maintenance treatment during the follow-up period and 181/260 (69.6%) of them were still on therapy; of these, the majority (55%) had been treated with PPIs, 35% had been treated with H2 receptor agonists and the remaining with non-antisecretory agents. Among patients treated with PPIs during the last year (100 subjects), 65% were taking a full dose, i.e. the dose usually used for acute therapy, and the remaining 35% were taking a half dose. In either case, only 44% were using a continuous therapy, whereas the remaining 48% were using an intermittent one and only 8% used a true on-demand therapy. One hundred and ninety-three out of 260 included patients underwent repeat endoscopy during the follow-up period. An average number of 1.5 symptomatic relapses per patient/year of follow-up were observed with an average of 1.6 ± 0.3 (SD) repeat endoscopies performed during the follow-up. Reason for repeat endoscopy was almost always symptom relapse. Despite active therapy, a progression to erosive gastro-esophageal reflux disease (ERD) was found in 58 patients (30.0%) overall; 72% of these cases were Los Angeles grade A or B.

In the univariate analysis, factors found to be significantly associated with the development of esophagitis were smoking, the presence of severe or nocturnal regurgitation and supine reflux time > 1.2% (but not upright or total reflux time), as well as the absence of continuous use of PPI therapy (Table 2). Interestingly, neither the age of the patient nor the BMI value (and in particular a BMI > 30) were found to influence the development of esophagitis. Table 3 shows the pH-metry parameters and the BMI values at presentation of those patients showing a progression vs. those not showing development of esophagitis.

| Risk factor | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

| Smoking | 3.1 (1.6-6.04) | 0.0006 |

| Regurgitation > 1/wk | 3.5 (1.9-6.6) | 0.0001 |

| Severe regurgitation | 2.6 (1.35-4.8) | 0.005 |

| Nocturnal regurgitation | 2.4 (1.2-4.7) | 0.01 |

| Supine reflux time > 1.2 | 5.3 (0.8-38.9) | 0.03 |

| Continuing PPI therapy | 0.3 (0.1-0.6) | 0.001 |

| % time of esophageal pH < 4 | BMI values (kg/m2) | |||

| Total | Upright | Supine | ||

| Patients developing esophagitis at follow-up | 5.1 ± 1.6 | 3.2 ± 2.6 | 6.2 ± 2.4 | 25.2 ± 3.6 |

| Patients not developing esophagitis at follow-up | 7.2 ± 5.6 | 6.2 ± 7.2 | 6.9 ± 8.5 | 25.3 ± 0.5 |

| P value | > 0.5 | > 0.5 | > 0.5 | > 0.5 |

In multivariate logistic regression analysis, only two factors were found to be independent predictors of development of esophagitis: smoking habit and the use of a continuous PPI therapy (Table 4).

| Risk factor | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

| Smoking | 2.9 (1.4-6.2) | 0.0055 |

| Ongoing PPI therapy | 0.2 (0.09-0.7) | 0.04 |

This retrospective study clearly shows that during a relatively long follow-up conducted in a sample of patients with NERD and pathological acid reflux, esophagitis develops in a clinically relevant proportion of patients (roughly one quarter); even in those undergoing a maintenance treatment. Smoking and the lack of a continuous PPI therapy are the only factors independently associated with the development of esophagitis, which, in our study, was predominantly grade A or B according to Los Angeles classification.

Our retrospective study is the largest ever conducted in a population of NERD patients further categorized on the basis of a pathological pH-monitoring.

We preferred to include only patients in whom an abnormal acid exposure could be demonstrated by 24-h esophageal pH monitoring for two main reasons: (1) to replicate the inclusion criteria we used in a previously published paper[11] and (2) to deal with a more homogeneous GERD patient population. In fact, as already demonstrated by others, a significant proportion of presumed NERD patients defined on the basis of symptoms alone do not have GERD[12]. It has been shown that, on the whole, pH testing is abnormal in about 45% of NERD patients, compared with 75% of patients with erosive esophagitis and 93% of patients with Barrett’s esophagus[13]. Thus, our population sample is not representative of the NERD population at large, but reflects a more homogenous subgroup of NERD patients, which can be defined as having a “true” acid-related NERD. In fact, whereas the majority of NERD patients with abnormal pH test have > 75% of heartburn occurring during an acid reflux event, this happens in only 10% of NERD patients with a negative pH test[13]. The particular selection of our patients may be viewed as a limitation as far as the translational capability of the results. On the other hand, the patients have been more precisely defined than solely on the basis of presence of symptoms and negativity of endoscopic features. The natural history of patients such as ours is at present incompletely known; in a previous retrospective study of a small cohort of pH test-positive NERD patients we demonstrated a progression to erosive esophagitis in 5 out of 33 patients treated over a 6 mo period with antacids and/or prokinetics[11]. In a subsequent study[10], we extended the observation time of the original patient group up to a median duration of 10 years. We found that almost all the patients we were able to trace (28/29) became affected by GERD symptoms when antisecretory drugs were discontinued, and therefore the majority (75%) were on such a therapy due to GERD symptoms. In addition, esophagitis was found in the vast majority of subjects in whom repeat endoscopy was performed (18/28). Thus, a considerable proportion of the original patient cohort indeed showed a progression from nonerosive to erosive disease within a long enough (> 5 years) time interval.

Other studies, such as that undertaken by Schindlbeck et al[14] or by McDougall et al[15], support the concept that a progression to esophagitis occurs at least in a proportion of NERD patients with a positive pH test at presentation. These results are in keeping with those recently published by Fullard et al[16], who performed a systematic review of studies conducted on GERD patients. In their review, they found that the annual progression rate for NERD patients (not further characterized by pH monitoring) ranged between 0% and 30%.

The multivariate analysis in our study found only two factors were independent determinants of a negative outcome, i.e. the development of esophagitis; namely smoking and the lack of a continuous PPI therapy.

These results seem to indicate that the information obtained with esophageal pH-monitoring in NERD patients is not useful to predict the potential progression of such patients toward erosive esophagitis. This has already been observed in the literature in the past; for example, in our previous study[11] conducted on a small and different patient sample, we found that patients who developed endoscopic esophagitis did not have a more severe baseline pattern of GER pH-metrically measured compared with those who did not develop esophageal mucosal damage. Similarly, Cadiot et al[17], in a multivariate analysis of factors predicting the development of esophagitis in patients with GERD symptoms, found that three independent factors contributed significantly to differentiating between patients with and without esophagitis; namely basal lower esophageal sphincter pressure, peak acid output and the number of reflux episodes during a 24 h period lasting more than 5 min, but not the total esophageal acid exposure time. Also a stepwise regression analysis, conducted on 66 GERD patients and 16 asymptomatic controls, found that hiatal hernia size and basal lower esophageal sphincter pressure, but not esophageal acid exposure or number of reflux episodes during a 24 h period lasting more than 5 min, significantly predicted presence and severity of esophagitis[18]. Moreover, Labenz et al[19] in a very large prospective study involving more than 6000 GERD patients (The ProGERD Study Initiative) found that no single factor or combination of factors was capable of predicting the presence of esophageal mucosal damage at multivariate analysis. In a case-control study of nearly 5000 patients with and without endoscopic reflux esophagitis investigated with a multivariate regression logistic analysis, Avidan et al[20] found that the only statistically significant factor associated with development of esophagitis was the presence of hiatal hernia. In both studies, however, no pH esophageal recording was performed. Moreover, all these studies were conducted on a mixed GERD population, e.g. patients with and without erosive esophagitis, and aimed at finding factors capable to discriminate these two categories.

Our study followed a different approach; we followed up a cohort of NERD patients and tried to locate factors potentially related to evolution into erosive esophagitis. The only similar study we were able to find in the literature is a study conducted in Japan, in which 47 patients with symptomatic GERD but without esophagitis (NERD) and 450 control subjects were endoscopically investigated at yearly intervals for 5 years, apparently without receiving any antisecretory therapy during this period[21]. The researchers found that among the group of NERD patients, esophagitis developed in 31.9% as compared with 11.3% in the control group (P < 0.01), and that the risk of developing esophagitis was significantly related to absence of Helicobacter pylori infection (P < 0.01), absence of gastric mucosal atrophy (P < 0.01), elevated triglycerides during the 5-year follow-up (P < 0.05), and an elevated BMI (P < 0.05), with a Cox proportional hazard model[21]. This study is however hardly transferable to clinical practice due to exclusion of adequate therapy during the 5-year of follow-up, which in our opinion is an insurmountable ethical drawback of the investigation.

The apparent lack of a relationship between extent of esophageal acid exposure time (and other pathophysiologic parameters of reflux and of esophageal motility) and development of esophagitis has been taken into consideration recently[22], and it has been suggested that the majority of investigations conducted so far have overlooked the resistance of the esophageal mucosa. Although the effect of smoking on GERD symptoms and lesions is not clear-cut, it probably acts on different pathogenetic sites, including mucosal resistance. Smoking may in fact promote GER by several mechanisms including; attenuation of the tone at the lower esophageal sphincter[23,24], a decrease in salivary flow and bicarbonate secretion with a resultant prolongation of acid clearance[25], and a delay in gastric emptying[26,27]. Some additional effects of smoking and nicotine that may be relevant to GERD are; an increase in gastric acid and pepsin secretion, augmentation of duodeno-gastric bile reflux and attenuation of the protective mechanisms of the gastric mucosa, such as synthesis of prostaglandins, mucus and epidermal growth factor[28]. Finally, in a recent study conducted on a NERD population which included a pathological pH investigation, smoking was found to be an independent predictor of GERD symptoms at multiple linear regression analysis[29].

In conclusion, our study shows that progression to ERD occurs in a considerable proportion of NERD patients (close to 5% per year) despite standard therapy, whereas symptomatic relapse occurs more frequently than once per year. Factors consistently and independently influencing this progression are smoking and the lack of a continuous PPI therapy during the follow-up period.

The natural history of nonerosive gastro-esophageal reflux disease (NERD) is not entirely known. In particular, data are lacking regarding the subgroup of NERD patients with abnormal esophageal pH monitoring. The authors conducted a study to assess the fate of these patients who were followed for a mean of 5 years after the index evaluation.

To evaluate by means of a multivariate analysis potential factors leading to a progression of the disease, e.g. the development of mucosal lesions.

The present study showed that progression to erosive gastro-esophageal reflux disease occurred in about 5% of their NERD patients per year, despite therapy. Only two factors consistently and independently influenced progression: smoking and absence of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy.

Due to the clinically relevant number of NERD patients evolving to esophagitis, it is conceivable that the present guidelines for endoscopy in gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) should be changed. In particular, the authors propose the repetition of upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy at least once every 5 years.

The authors have conducted a retrospective study which provides useful information regarding the natural history of nonerosive reflux disease patients and the potential factors leading to esophageal mucosal lesions over 5 years of follow-up.

Peer reviewer: Radha K Dhiman, Associate Professor, Department of Hepatology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh 160012, India

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Eisen G. The epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease: what we know and what we need to know. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:S16-S18. |

| 2. | Locke GR 3rd, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd. Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1448-1456. |

| 3. | Quigley EM, DiBaise JK. Non-erosive reflux disease: the real problem in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2001;33:523-527. |

| 4. | Glise H, Hallerbäck B, Wiklund I. Quality of life: a reflection of symptoms and concerns. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1996;221:14-17. |

| 5. | Smout AJPM. Endoscopy-negative acid reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11 Suppl 2:81-85. |

| 6. | Fass R, Fennerty MB, Vakil N. Nonerosive reflux disease--current concepts and dilemmas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:303-314. |

| 7. | Carlsson R, Dent J, Watts R, Riley S, Sheikh R, Hatlebakk J, Haug K, de Groot G, van Oudvorst A, Dalväg A. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care: an international study of different treatment strategies with omeprazole. International GORD Study Group. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:119-124. |

| 8. | Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920; quiz 1943. |

| 9. | Baldi F, Ferrarini F, Longanesi A, Bersani G. Ambulatory 24-hour oesophageal pH monitoring in normal subjects: a multicentre study in Italy. G.I.S.M.A.D. GOR Study Group. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1991;23:477-480. |

| 10. | Pace F, Bollani S, Molteni P, Bianchi Porro G. Natural history of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease without oesophagitis (NERD)--a reappraisal 10 years on. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:111-115. |

| 11. | Pace F, Santalucia F, Bianchi Porro G. Natural history of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease without oesophagitis. Gut. 1991;32:845-848. |

| 12. | Tack J, Fass R. Review article: approaches to endoscopic-negative reflux disease: part of the GERD spectrum or a unique acid-related disorder? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19 Suppl 1:28-34. |

| 13. | Martinez SD, Malagon IB, Garewal HS, Cui H, Fass R. Non-erosive reflux disease (NERD)--acid reflux and symptom patterns. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:537-545. |

| 14. | Schindlbeck NE, Klauser AG, Berghammer G, Londong W, Müller-Lissner SA. Three year follow up of patients with gastrooesophageal reflux disease. Gut. 1992;33:1016-1019. |

| 15. | McDougall NI, Johnston BT, Collins JS, McFarland RJ, Love AH. Three- to 4.5-year prospective study of prognostic indicators in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:1016-1022. |

| 16. | Fullard M, Kang JY, Neild P, Poullis A, Maxwell JD. Systematic review: does gastro-oesophageal reflux disease progress? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:33-45. |

| 17. | Cadiot G, Bruhat A, Rigaud D, Coste T, Vuagnat A, Benyedder Y, Vallot T, Le Guludec D, Mignon M. Multivariate analysis of pathophysiological factors in reflux oesophagitis. Gut. 1997;40:167-174. |

| 18. | Jones MP, Sloan SS, Rabine JC, Ebert CC, Huang CF, Kahrilas PJ. Hiatal hernia size is the dominant determinant of esophagitis presence and severity in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1711-1717. |

| 19. | Labenz J, Jaspersen D, Kulig M, Leodolter A, Lind T, Meyer-Sabellek W, Stolte M, Vieth M, Willich S, Malfertheiner P. Risk factors for erosive esophagitis: a multivariate analysis based on the ProGERD study initiative. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1652-1656. |

| 20. | Avidan B, Sonnenberg A, Schnell TG, Sontag SJ. Risk factors for erosive reflux esophagitis: a case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:41-46. |

| 21. | Kawanishi M. Will symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease develop into reflux esophagitis? J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:440-443. |

| 22. | Bortolotti M. Natural history of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: the neglected factor. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1204-1208. |

| 23. | Kahrilas PJ, Gupta RR. Mechanisms of acid reflux associated with cigarette smoking. Gut. 1990;31:4-10. |

| 24. | Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ. Smoking and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:837-842. |

| 25. | Trudgill NJ, Smith LF, Kershaw J, Riley SA. Impact of smoking cessation on salivary function in healthy volunteers. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:568-571. |

| 26. | Miller G, Palmer KR, Smith B, Ferrington C, Merrick MV. Smoking delays gastric emptying of solids. Gut. 1989;30:50-53. |

| 27. | Scott AM, Kellow JE, Shuter B, Nolan JM, Hoschl R, Jones MP. Effects of cigarette smoking on solid and liquid intragastric distribution and gastric emptying. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:410-416. |

| 28. | Endoh K, Leung FW. Effects of smoking and nicotine on the gastric mucosa: a review of clinical and experimental evidence. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:864-878. |

| 29. | Zimmerman J. Irritable bowel, smoking and oesophageal acid exposure: an insight into the nature of symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1297-1303. |