Published online Nov 28, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5610

Revised: September 24, 2009

Accepted: October 1, 2009

Published online: November 28, 2009

AIM: To study the relationship between the polymorphisms in some cytokines and the outcome of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.

METHODS: Samples were obtained from 203 patients infected with HBV and/or HCV while donating plasma in 1987, and 74 controls were obtained from a rural area of North China. Antibodies to HBV or HCV antigens were detected by enzyme-linked immunoassay. The presence of viral particles in the serum was determined by nested reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Hepatocellular injury, as revealed by alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase level, was detected by a Beckman LX-20 analyzer. DNA was extracted from blood cells. Then, the single nucleotide polymorphisms of IL-2-330, IFN-γ+874, IL-10-1082/-592 and IL-4-589 were investigated by restriction fragment length polymorphism-PCR or sequence specific primer-PCR.

RESULTS: Persistent infection with HBV, HCV, and HBV/HCV coinfection was associated with IL-2-330 TT genotype and T allele, IFN-γ+874 AA genotype, and IL-10-1082 AA genotype. The clinical outcome of HBV and/or HCV infection was associated with IL-2-330 TT genotype and T allele, IFN-γ+874 AA genotype, and IL-10-1082 AA genotype. IL-2-330 GG genotype frequency showed a negative correlation with clinical progression, IL-10-1082 AA genotype frequency showed a positive correlation and IL-10-1082 AG genotype frequency showed a negative correlation with clinical progression. HCV RNA positive expression was associated with IL-10-1082 AA genotype and the A allele frequency. Abnormal serum ALT level was associated with IL-10-592 AC genotype frequency and IL-4-589 CC genotype, CT genotype, and the C allele.

CONCLUSION: These results suggest that polymorphisms in some cytokine genes influence persistent HBV and HCV infection, clinical outcome, HCV replication, and liver damage.

- Citation: Gao QJ, Liu DW, Zhang SY, Jia M, Wang LM, Wu LH, Wang SY, Tong LX. Polymorphisms of some cytokines and chronic hepatitis B and C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(44): 5610-5619

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i44/5610.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.5610

The natural outcome in hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection varies dramatically among individuals. Infection with HCV is self-limited in a fortunate minority, while the majority of subjects develop persistent (chronic) infection[1,2]. Although infection with HBV in adults progresses to the chronic phase in about 5%[3], among those individuals with persistent HBV or HCV infection, the majority develop chronic hepatitis (CH), progressive fibrosis and even liver cancer[4,5]. However, there are some cases that never evolve into any significant liver disease within the patient’s natural lifespan[6,7]. It remains unknown why patients infected with HBV and/or HCV frequently turn to be chronic and the outcome of HBV and/or HCV infection dramatically varies. Besides the pathogenesis of viral factors, the most important factor is the different immune response to HBV or HCV infection between individuals. For example, in patients infected with HBV/HCV, some show a strong reduction in CD4+ T-helper (Th) and CD8+ cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte (CTL) responses. This is likely to be crucial in clearance of acute viremia[8-10]. Another factor is thought to be immune tolerance to HBV/HCV infection. This contributes to explaining the different susceptibility to HBV/HCV infection. Many manifestations show that the immunity level of host correlates with relevant gene polymorphisms, especially with single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the promoter region that regulates gene expression. Furthermore, the gene polymorphisms probably determine the outcome of the infection. This study investigated the screened Th1 cytokines, interleukin (IL)-2 (-330), interferon (IFN)-γ (+874), and Th2 cytokines, IL-10 (-1082, -592) and IL-4 (-589) as candidate genes, to investigate the outcome of HBV/HCV infection.

We recruited 277 Han Chinese individuals from a rural area of Northern China (137 male and 140 female, aged 30-70 years, mean age 50.20 ± 10.43 years), including 203 that were infected with HBV and/or HCV when they donated plasma in 1987, and 74 controls who had cleared HBV and HCV spontaneously. Plasma samples were evaluated by nested reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (nRT-PCR) and PCR. We diagnosed and excluded 28 patients with fatty liver. The infections had been diagnosed in 1993. Written informed consent for enrolling in the study was obtained from all the subjects. Patients were classified into the following groups. (1) Controls: 74 individuals (34 male and 40 female, mean age 48.61 ± 9.39 years) who were negative for HBV and HCV antibodies. (2) Persistent HCV infection: 55 individuals (28 male and 27 female, mean age 49.42 ± 10.01 years) who were positive for HCV antibodies but negative for HBV antibodies. (3) Persistent HBV infection: 69 individuals (39 male and 30 female, mean age 52.74 ± 13.17 years) who had hepatitis B surface antigen and/or anti-hepatitis B core and/or anti-hepatitis B e antibodies, without HCV antibodies. (4) Persistent HBV and HCV coinfection: 79 individuals (36 male and 43 female, mean age 50.01 ± 8.56 years) who had antibodies to HBV and HCV.

Antibodies to HBV or HCV antigens were detected with an enzyme-linked immunoassay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Shanghai Kehua Bio-engineering Co. Ltd). The presence of hepatitis C viral particles in serum was determined by nRT-PCR. Hepatocellular injury, as revealed by alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase level, was detected by a Beckman LX-20 analyzer. Clinical outcomes were diagnosed by evidence of viremia, liver transaminases and abnormal ultrasonography. Patients were diagnosed into four progressive hepatitis groups. (1) Healthy group: individuals negative for HBV and HCV antibodies, with normal liver transaminase levels and ultrasonography. (2) Mild CH group: patients with antibodies to HBV and/or HCV with mild abnormal liver transaminase and ultrasonography, but no evidence of viremia. (3) Moderate/severe CH: patients with antibodies to HBV and/or HCV with evidence of viremia, abnormal liver transaminase and/or abnormal ultrasonography. (4) Cirrhosis group: patients with antibodies to HBV and/or HCV and significantly abnormal ultrasonography. The diagnosis was performed using established methods for confirming cirrhosis[11], with or without evidence of viremia, which had abnormal liver transaminase levels.

Blood specimens were collected in sodium citrate sterile tubes. Genomic DNA was extracted from 2-mL samples of whole blood and subsequently stored at -20°C for genotype analysis. Genomic DNA extraction was performed using the guanidine-HCl method[12].

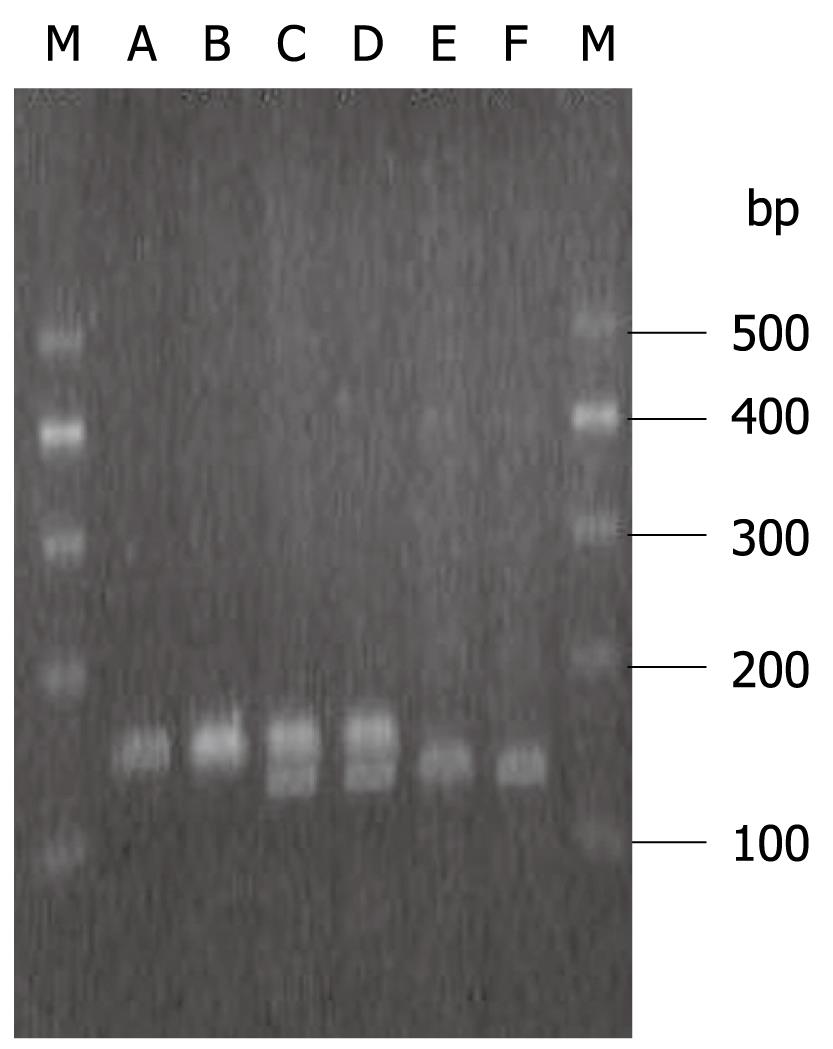

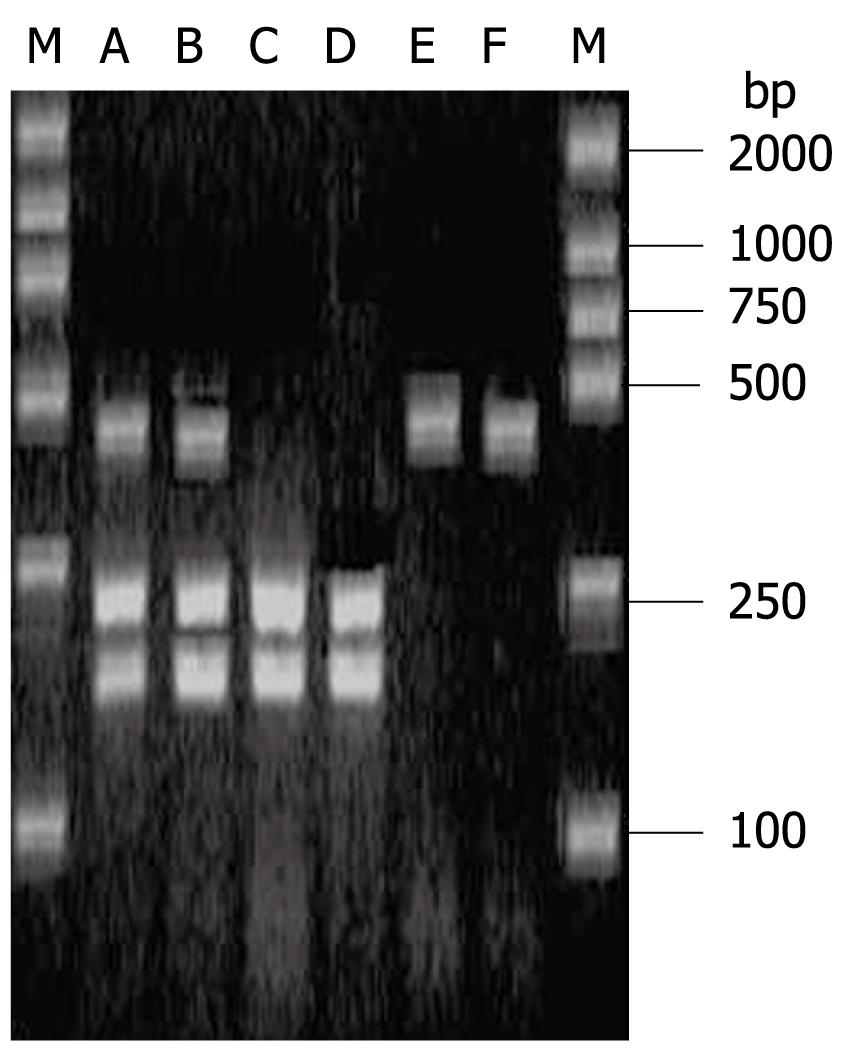

Gene amplification: IL-2-T330G, IL-4-C589T and IL-10-A592C gene polymorphisms were typed by restriction fragment length polymorphism-PCR. The primer sequences used are listed in Table 1. The 25-μL final PCR volume was as follows: 20 ng DNA, 2.5 μL 10 × PCR Buffer (100 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 500 mmol/L KCl), 200 μmol/L dNTPs (400 μmol/L dNTPs for IL-4-C589T), 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2 (2.0 mmol/L MgCl2 for IL-2-T330G), 10 pmol each primer, 1 U Taq polymerase (TaKaRa Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Dalian, China). PCR was carried out in an AmpGene DNA thermal cycler 4800 (America PE Corporation). After the initial denaturation step (95°C for 2 min), the 35 cycles specified in Table 1 were employed. After the final cycle, the samples were kept at 72°C for 7 min. Successful amplification was confirmed by using 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. The product size of each cytokine was described as in Table 2.

| SNP position | Polymorphism | Primer sequence 5’-3’ | PCR conditions |

| IL-2 -330 | T→G | F: 5'-TATTCACATGTTCAGTGTAGTTCT-3' | 94°C, 48°C, 72°C for 1 min |

| R: 5'-ACATTAGCCCACACTTAGGT-3' | |||

| IL-4 -589 | C→T | F: 5'-ACTAGGCCTCACCTGATACG-3' | 94°C, 57°C, 72°C for 30 s |

| R: 5'-GTTGTAATGCAGTCCTCCTG-3' | |||

| IL-10 -592 | A→C | F: 5'-CCTAGGTCACAGTGACGTGG-3' | 94°C/30 s, 60°C/45 s, 72°C/60 s |

| R: 5'-GGTGAGCACTACCTGACTAGC-3' |

| SNP position | Product size (bp) | Restriction enzyme | Digestion fragments (bp) |

| IL-2-330 T/G | 150 | MaeI (Bio Basic Inc.) | 150 |

| 26 + 124 | |||

| IL-4-589 T/C | 252 | BsmFI (New England BioLabs) | 252 |

| 60 + 192 | |||

| IL-10-592 C/A | 412 | RsaI (Bio Basic Inc.) | 412 |

| 236 + 176 |

Restriction enzyme digestion: Restriction enzyme digestion was performed in 10-μL volumes as follows: 2 U restriction enzyme, 1 μL 10 × Buffer, and the appropriate PCR product (4 μL IL-2-T330G, 3 μL IL-4-C589T and 1 μL 10 × BSA, 5 μL IL-10-A592C). The digestion reaction of IL-2-T330G and IL-10-A592C was incubated at 37°C for 10 h, and the IL-4-C589T reaction at 65°C for 15 h. The digestive products were visualized on 3% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. The wild or mutant genotype was characterized by enzyme digestion fragments, as in Table 2.

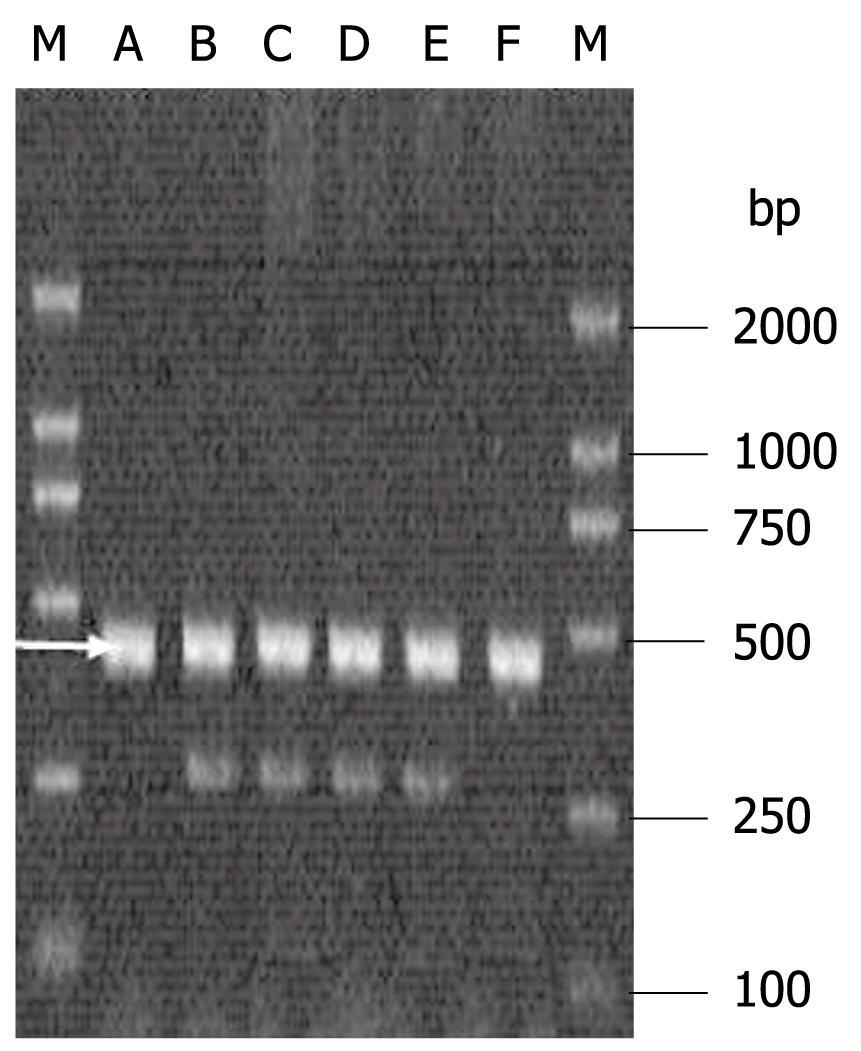

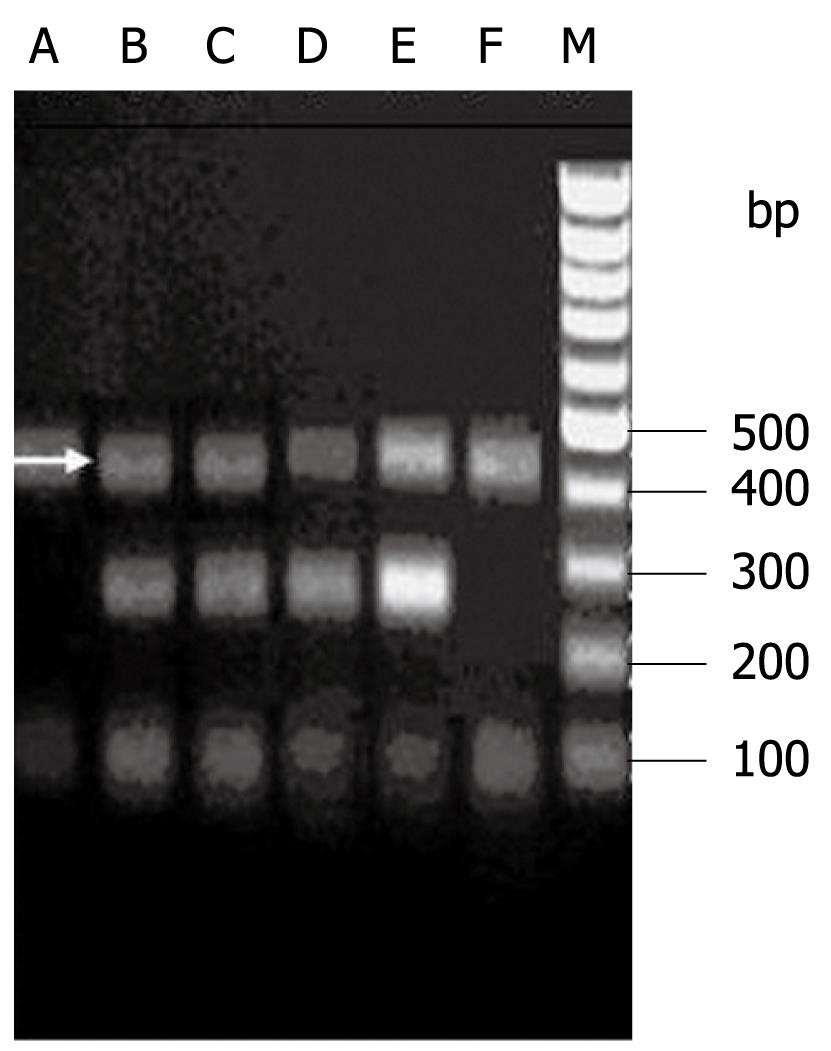

IL-10-G1082A and IFN-γ+T874A gene polymorphisms were detected by sequence specific primer-PCR technique. For each sample, two parallel reactions were performed. For IL-10-1082, the forward allele-specific primers were either 5'-ACTACTAAGGCTTCTTTGGGAA-3' (for IL-10 allele A) or 5'-CTACTAAGGCTTCTTTGGGAG-3' (for IL-10 allele G), and the antisense primer was 5'-CAGTGCCAACTGAGAATTTGG-3'. The product size was 258 bp. A human growth hormone sequence was used as an internal control. The control primers were 5'-GCCTTCCCAACCATTCCCTTA-3' and 5'-TCACGGATTTCTGTTGTGTTTC-3', and the product size was 429 bp. The 20-μL final reaction volume contained: 2.0 μL 10 × PCR Buffer (100 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 500 mmol/L KCl), 200 μmol/L dNTPs, 2.0 mmol/L MgCl2, 3.75 μmol/L specific primer, 0.09 μmol/L control primer, 20 ng DNA, and 0.5 U Taq polymerase. PCR was carried out in an AmpGene DNA thermal cycler 4800. The cycling conditions were 95°C for 2 min, and 10 cycles for 1 min at 95°C, 50 s at 65°C and 50 s at 72°C, followed by 20 cycles for 1 min at 95°C, 50 s at 59°C, and 50 s at 72°C, followed by a final extension for 7 min at 72°C. The PCR products were visualized on 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide.

For IFN-γ+874, the forward allele-specific primers were 5'-TTCTTACAACACAAAATCAAATCT-3' (for allele T) or 5'-TTCTTACAACACAAAATCAAATCA-3' (for allele A), and the anti-sense primer was 5'-TCAACAAAGCTGATACTCCA-3'. The product size was 262 bp. A human growth hormone sequence was used as an internal control. The control forward primer was 5'-TATGATTCTGGCTAAGGAATG-3' and the anti-sense primer was 5'-TCAACAAAGCTGATACTCCA-3. The product size was 440 bp. The 20-μL final reaction volume contained 2.0 μL 10 × PCR buffer (100 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 500 mmol/L KCl), 200 μmol/L dNTPs, 2.0 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.5 μmol/L specific primer, 0.1 μmol/L former control primer, 20 ng DNA, and 0.5 U Taq polymerase. PCR was carried out in an AmpGene DNA thermal cycler 4800. The cycling conditions were 94°C for 2 min, and 10 cycles for 30 s at 94°C, 40 s at 60°C and 40 s at 72°C, followed by 25 cycles for 30 s at 94°C, 40 s at 56°C, and 50 s at 72°C, followed by a final extension for 7 min at 72°C. The PCR products were visualized on 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide.

The data were tested by the χ2 test for the goodness of fit to the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) between the observed and expected genotype values. The frequencies of the alleles and genotypes among the groups were compared by the χ2 test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We calculated the OR and 95% CI.

An HWE test was performed for all cytokine polymorphisms investigated in this study (Table 3). The distribution of these observed genotypes was not significantly different from the expected distribution according to HWE, except the IL-10-1082 polymorphisms, which revealed a deviation from HWE because of the lower frequency of wild-type homozygosity (the observed vs the expected frequency was 1.08% vs 10.91%). In IL-2-330, IL-4-589, IL-10-1082, IL-10-592 and IFN-γ+874 gene polymorphisms, there were no significant differences in age and sex (P > 0.05).

| Locus | Observed homozygosity (%) | Expected homozygosity (%) | P value | ||

| Wild-type genotype | Mutant genotype | Wild-type genotype | Mutant genotype | ||

| IL-2-330 | 40.79 | 14.08 | 40.14 | 13.43 | > 0.05 |

| IFN-γ+874 | 11.55 | 35.02 | 14.65 | 38.10 | > 0.05 |

| IL-4-589 | 3.25 | 50.54 | 6.94 | 54.24 | > 0.05 |

| IL-10-592 | 42.60 | 10.83 | 43.40 | 11.64 | > 0.05 |

| IL-10-1082 | 1.08 | 35.02 | 10.91 | 44.85 | < 0.05 |

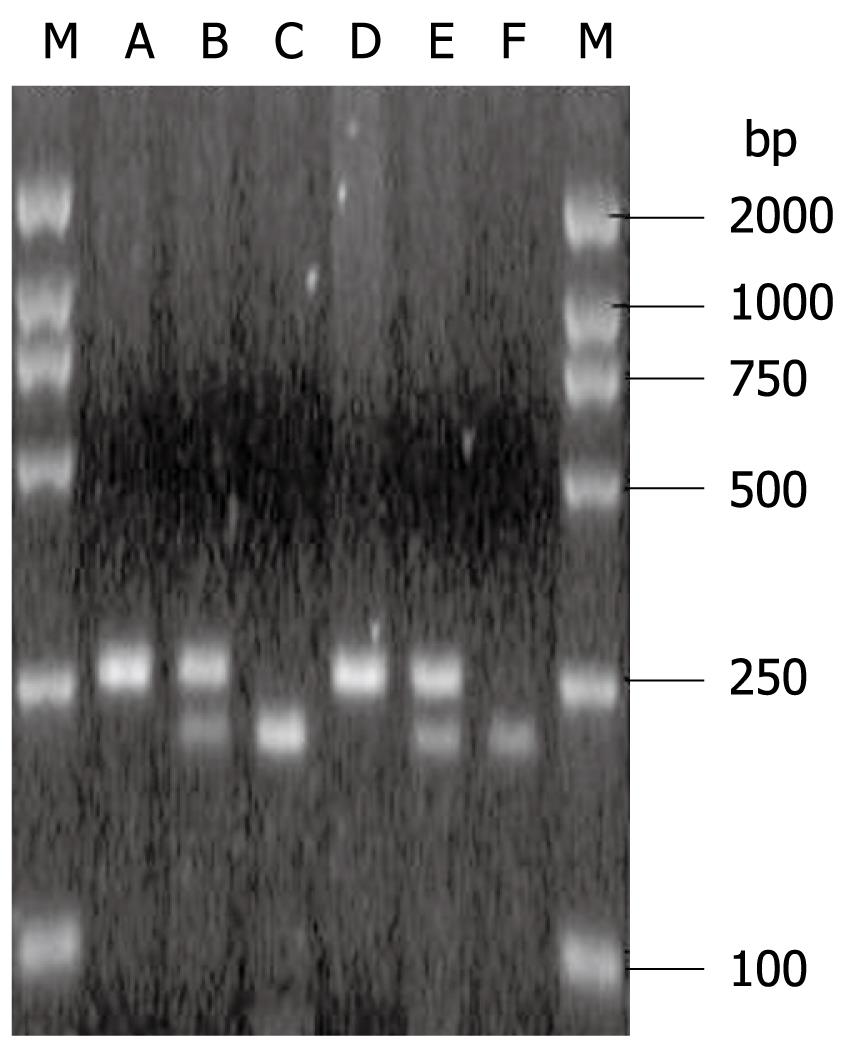

IL-2-330 TT, -330 GG and -330 TG are shown in Figure 1. The IL-2-330 polymorphisms showed obvious association with persistent HBV and/or HCV infection. IL-2-330 TT was associated with an increased risk, but IL-2-330 GG with a reduced risk of persistent HBV and/or HCV infection. The OR and 95% CI for IL-2-330 TT compared with -330 GG in HCV infection, HBV infection and HBV/HCV coinfection were 3.46 (1.17-10.20), 7.14 (2.13-23.81) and 2.93 (1.15-7.46), respectively. However, IL-2-330 TT/GG did not differ significantly between patients with HBV and/or HCV infection. The IL-2-330 T allele was associated with an increased risk, but the IL-2-330 G allele was associated with a reduced risk of chronic HCV and/or HBV infection. The OR and 95% CI for the IL-2-330 T allele compared with -330 G allele in HCV infection, HBV infection, and HBV/HCV coinfection were 1.82 (1.09-3.03), 2.26 (1.39-3.69) and 1.73 (1.10-2.73), respectively. However, the IL-2-330 T/G allele did not differ significantly between HBV and/or HCV infection (Table 4).

| Genotype allele | Controls (n = 74) | HCV infection (n = 55) | HBV infection (n = 69) | HBV/HCV coinfection (n = 79) | χ2 | P |

| IL-2-330 | ||||||

| TT | 22 (29.7) | 24 (43.6) | 33 (47.8) | 34 (43.0) | ||

| GG | 19 (25.7) | 6 (10.9) | 4 (5.8) | 10 (12.7) | 14.24 | 0.03 |

| TG | 33 (44.6) | 25 (45.5) | 32 (46.4) | 35 (44.3) | ||

| T | 77 (52.0) | 73 (66.4) | 98 (71.0) | 103 (65.2) | 12.33 | 0.01 |

| G | 71 (48.0) | 37 (33.6) | 40 (29.0) | 55 (34.8) | ||

| IFN-γ+874 | ||||||

| TT | 7 (9.5) | 5 (9.1) | 9 (13.0) | 11 (13.9) | ||

| AA | 14 (18.9) | 23 (41.8) | 25 (36.2) | 35 (44.3) | 16.15 | 0.01 |

| TA | 53 (71.6) | 27 (49.1) | 35 (50.7) | 33 (41.8) | ||

| T | 67 (45.3) | 37 (33.6) | 53 (38.4) | 55 (34.8) | 4.87 | 0.18 |

| A | 81 (54.7) | 73 (66.4) | 85 (61.6) | 103 (65.2) | ||

| IL-10-1082 | ||||||

| GG | 1 (1.4) | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| AA | 16 (21.6) | 21 (38.2) | 27 (39.1) | 33 (41.8) | 13.05 | 0.04 |

| GA | 57 (77.0) | 32 (58.2) | 42 (60.9) | 46 (58.2) | ||

| G | 59 (39.9) | 36 (32.7) | 42 (30.4) | 46 (29.1) | 4.65 | 0.20 |

| A | 89 (60.1) | 74 (67.3) | 96 (69.6) | 112 (70.9) | ||

| IL-10-592 | ||||||

| AA | 34 (45.9) | 20 (36.4) | 29 (42.0) | 35 (44.3) | ||

| CC | 9 (12.2) | 6 (10.9) | 9 (13.0) | 6 (7.6) | 2.83 | 0.83 |

| AC | 31 (41.9) | 29 (52.7) | 31 (44.9) | 38 (48.1) | ||

| A | 99 (66.9) | 69 (62.7) | 89 (64.5) | 108 (68.4) | 1.10 | 0.78 |

| C | 49 (33.1) | 41 (37.3) | 49 (35.5) | 50 (31.6) | ||

| IL-4-589 | ||||||

| CC | 5 (6.8) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.5) | ||

| TT | 38 (51.4) | 28 (50.9) | 35 (50.7) | 39 (49.4) | 4.41 | 0.62 |

| CT | 31 (41.9) | 26 (47.3) | 33 (47.8) | 38 (48.1) | ||

| C | 41 (27.7) | 28 (25.5) | 35 (25.4) | 42 (26.6) | 0.26 | 0.97 |

| T | 107 (72.3) | 82 (74.5) | 103 (74.6) | 116 (73.4) |

IFN-γ+874 TT, +874 AA and +874 TA are shown in Figure 2. The IFN-γ+874 polymorphisms showed a significant association with persistent HBV and/or HCV infection. IFN-γ+874 AA was associated with an increased risk, but IFN-γ+874 TA with a reduced risk of persistent HBV and/or HCV infection. The OR and 95% CI for IFN-γ+874 AA compared with +874 TA in HCV infection, HBV infection, and HBV/HCV coinfection were 3.23 (1.43-7.25), 2.70 (1.24-5.92) and 4.02 (1.88-8.55), respectively. However, IFN-γ+874 AA/TA did not differ significantly between HBV and/or HCV infection. The IFN-γ+874 T/A alleles did not differ significantly between all groups (Table 4).

IL-10-1082 GG, -1082 AA and -1082 GA are shown in Figure 3. The IL-10-1082 polymorphisms showed a significant association with persistent HBV and/or HCV infection. IL-10-1082 AA was associated with an increased risk, but -1082 AG with a reduced risk of persistent HBV and/or HCV infection. The OR and 95% CI for IL-10-1082 AA compared with -1082 AG in HCV infection, HBV infection, and HBV/HCV coinfection were 2.34 (1.07-5.10), 2.29 (1.10-4.78) and 2.56 (1.25-5.21), respectively. However, IL-10-1082 AA/AG did not differ significantly between the subjects with HBV and/or HCV infection. The IL-10-1082 A/G alleles did not differ obviously between any of the subjects (Table 4).

The IL-10-592 polymorphisms are shown in Figure 4. The IL-10-592 A/C polymorphisms did not differ significantly between any of the groups (Table 4).

IL-10-589 TT, -589 CC and -589 TC are shown in Figure 5. IL-4-589 T/C polymorphisms did not differ significantly between any of the groups (Table 4).

The IL-2-330 polymorphisms showed a significant association with the outcome of persistent HBV and/or HCV infection. IL-2-330 TT was associated with an increased risk, but -330 GG with a reduced risk of mild CH, moderate/severe CH, and cirrhosis. The OR and 95% CI for IL-2-330 TT compared with -330 GG genotype in patients with mild CH, moderate/severe CH, and cirrhosis were 3.42 (1.45-8.13), 3.29 (1.10-9.80), and 11.11 (1.32-90.91), respectively. However, IL-2-330 TT/GG did not differ significantly between patients with mild CH, moderate and severe CH, and cirrhosis. The IL-2-330 T allele was associated with an increased risk, but the -330 G allele was associated with a reduced risk of mild CH, moderate and severe CH, or cirrhosis. The OR and 95% CI for the -330 T allele compared with -330 G allele for patients with mild CH, moderate/severe CH and cirrhosis were 1.83 (1.20-2.80), 1.70 (1.02-2.82) and 2.75 (1.32-5.63), respectively. However, IL-2-330 polymorphisms did not differ significantly between patients with mild CH, moderate/severe CH, and cirrhosis (Table 5).

| Genotype | Control (n = 74) | Mild CH (n = 122) | Moderate/severe CH (n = 57) | Cirrhosis (n = 24) | χ2 | P |

| IL-2-330 | ||||||

| TT | 22 (29.7) | 54 (44.3) | 23 (40.4) | 13 (54.2) | ||

| GG | 19 (25.7) | 14 (11.4) | 6 (10.5) | 1 (4.2) | 13.46 | 0.04 |

| TG | 33 (44.6) | 54 (44.3) | 28 (49.1) | 10 (41.7) | ||

| T | 77 (52.0) | 163 (66.8) | 74 (64.9) | 36 (75.0) | 11.69 | 0.01 |

| G | 71 (48.0) | 81 (33.2) | 40 (35.0) | 12 (25.0) | ||

| IFN-γ+874 | ||||||

| TT | 8 (10.8) | 14 (11.5) | 5 (8.8) | 4 (16.7) | ||

| AA | 14 (18.9) | 48 (39.3) | 26 (45.6) | 9 (37.5) | 14.78 | 0.02 |

| TA | 52 (70.3) | 60 (49.2) | 26 (45.6) | 11 (45.8) | ||

| T | 68 (45.9) | 90 (36.9) | 36 (31.6) | 19 (39.6) | 5.68 | 0.13 |

| A | 80 (54.1) | 154 (63.1) | 78 (68.4) | 29 (60.4) | ||

| IL-10-1082 | ||||||

| GG | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| AA | 16 (21.6) | 44 (36.1) | 24 (42.1) | 13 (54.2) | 11.40 | 0.07 |

| GA | 57 (77.0) | 77 (63.1) | 32 (56.1) | 11 (45.8) | ||

| G | 59 (39.9) | 79 (32.4) | 34 (29.8) | 11 (22.9) | 5.85 | 0.12 |

| A | 89 (60.1) | 165 (67.6) | 80 (70.2) | 37 (77.1) | ||

| IL-10-592 | ||||||

| AA | 34 (45.9) | 51 (41.8) | 22 (38.6) | 11 (45.8) | ||

| CC | 9 (12.2) | 11 (9.0) | 8 (14.0) | 2 (8.3) | 2.50 | 0.87 |

| AC | 31 (41.9) | 60 (49.2) | 27 (47.4) | 11 (45.8) | ||

| A | 98 (66.2) | 163 (66.8) | 71 (62.3) | 33 (68.8) | 0.92 | 0.82 |

| C | 50 (33.8) | 81 (33.2) | 43 (37.7) | 15 (31.3) | ||

| IL-4-589 | ||||||

| CC | 3 (4.0) | 3 (2.4) | 3 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| TT | 38 (51.4) | 69 (54.8) | 24 (42.1) | 11 (45.8) | 4.58 | 0.60 |

| CT | 33 (44.6) | 54 (42.9) | 30 (52.6) | 13 (54.2) | ||

| C | 39 (26.4) | 58 (23.8) | 36 (31.6) | 13 (27.1) | 2.46 | 0.48 |

| T | 109 (73.6) | 186 (76.2) | 78 (68.4) | 35 (72.9) |

The IFN-γ+874 polymorphisms showed a significant association with the clinical outcome of persistent HBV and/or HCV infection. IFN-γ+874 AA was associated with an increased risk, but +874 TA with a reduced risk of mild CH, moderate/severe CH, and cirrhosis. There was significantly decreased IFN-γ+874 AA genotype frequency in cirrhosis compared with moderate/severe CH patients. The OR and 95% CI for IFN-γ+874 AA compared with +874 TA in patients with mild CH, moderate/severe CH, and cirrhosis were 3.09 (1.51-6.33), 3.85 (1.70-8.70) and 3.14 (1.08-9.17), respectively. The IFN-γ+874 T/A alleles did not differ between any of the groups (Table 5).

The IL-10-1082 polymorphisms showed a significant association with the clinical outcome of persistent HBV and/or HCV infection. IL-10-1082 AA was associated with an increased risk, but -1082 AG with a reduced risk of mild CH, moderate/severe CH, and cirrhosis. There was a significantly increased IL-10-1082 AA genotype frequency in cirrhosis compared with mild CH. IL-10-1082 AA showed a positive correlation with clinical outcome (γ = 0.99, P = 0.00), but the IL-10-1082 AG showed a negative correlation with clinical outcome (γ = -0.99, P = 0.00). The OR and the 95% CI for IL-10-1082 AA compared with -1082 AG in patients with mild CH, moderate/severe CH, and cirrhosis were 2.03 (1.03-3.98), 2.70 (1.24-5.88) and 4.26 (1.59-11.36), respectively. The IL-10-1082 G/A allele did not differ obviously in every group (Table 5).

The polymorphisms of IL-10-592 A/C and IL-4 -589 C/T did not differ significantly in every group (Table 5).

IL-10-1082 AA was associated with an increased risk, but -1082 AG was associated with a reduced risk of HCV RNA replication. The OR and 95% CI for IL-10-1082 AA compared with -1082 AG was 3.36 (1.67-6.76). IL-10-1082 A was associated with an increased risk, but -1082 G with a reduced risk of HCV RNA replication. The OR and 95% CI for IL-10-1082 A compared with -1082 G was 1.67 (1.08-2.57). The polymorphisms of IL-2-330, IFN-γ+874, IL-10-592 and IL-4-589 showed no association with HCV RNA replication (Table 6).

| HCV RNA - | HCV RNA + | χ2 | P | ALT < 80 U/L | ALT ≥ 80 U/L | χ2 | P | |

| IL-2-330 | ||||||||

| TT | 29 (37.2) | 39 (37.1) | 102 (41.8) | 11 (33.3) | ||||

| GG | 14 (17.9) | 14 (13.3) | 0.83 | 0.66 | 35 (14.3) | 4 (12.1) | 1.35 | 0.51 |

| TG | 35 (44.9) | 52 (49.5) | 107 (43.9) | 18 (54.5) | ||||

| T | 93 (59.6) | 130 (61.9) | 0.20 | 0.66 | 311 (63.7) | 40 (60.0) | 0.24 | 0.62 |

| G | 63 (40.4) | 80 (38.1) | 177 (36.3) | 26 (39.4) | ||||

| IFN-γ+874 | ||||||||

| TT | 13 (16.7) | 10 (9.5) | 29 (11.9) | 3 (9.1) | ||||

| AA | 28 (35.9) | 45 (42.9) | 2.36 | 0.31 | 85 (34.8) | 12 (36.4) | 0.23 | 0.89 |

| TA | 37 (47.4) | 50 (47.6) | 130 (53.3) | 18 (54.5) | ||||

| T | 63 (40.4) | 70 (33.3) | 1.92 | 0.17 | 188 (38.5) | 24 (36.4) | 0.12 | 0.74 |

| A | 93 (59.6) | 140 (66.7) | 300 (61.5) | 42 (63.6) | ||||

| IL-10-1082 | ||||||||

| GG | 1 (1.3) | 2 (1.9) | 3 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| AA | 14 (17.9) | 44 (41.9) | 12.27 | 0.00 | 81 (33.2) | 16 (48.5) | 3.25 | 0.20 |

| GA | 63 (80.8) | 59 (56.2) | 160 (65.6) | 17 (51.5) | ||||

| G | 91 (58.3) | 147 (70.0) | 5.36 | 0.02 | 166 (34.0) | 17 (25.8) | 1.79 | 0.18 |

| A | 65 (41.7) | 63 (128) | 322 (66.0) | 49 (74.2) | ||||

| IL-10-592 | ||||||||

| AA | 41 (52.6) | 44 (41.9) | 110 (45.1) | 8 (24.2) | ||||

| CC | 6 (7.7) | 11 (10.5) | 2.10 | 0.35 | 27 (11.1) | 3 (9.1) | 6.32 | 0.04 |

| AC | 31 (39.7) | 50 (47.6) | 107 (43.9) | 22 (66.7) | ||||

| A | 113 (72.4) | 138 (65.7) | 1.88 | 0.17 | 327 (67.0) | 38 (57.6) | 2.30 | 0.09 |

| C | 43 (27.6) | 72 (34.3) | 161 (33.0) | 28 (42.4) | ||||

| IL-4-589 | ||||||||

| CC | 3 (3.8) | 5 (4.8) | 6 (2.5) | 3 (9.1) | ||||

| TT | 48 (61.5) | 55 (52.4) | 1.53 | 0.47 | 132 (54.1) | 8 (24.2) | 12.46 | 0.02 |

| CT | 27 (34.6) | 45 (42.9) | 106 (43.4) | 22 (66.7) | ||||

| C | 33 (21.2) | 55 (26.2) | 1.24 | 0.27 | 118 (24.2) | 28 (42.4) | 9.97 | 0.00 |

| T | 123 (78.8) | 155 (73.8) | 370 (75.8) | 38 (57.6) |

IL-10-592 AC showed an increased risk, but -592 AA showed a reduced risk of abnormal ALT. The OR and 95% CI for IL-10-592 AC compared with -592 AA was 2.83 (1.21-6.63). The IL-10-592 A/C alleles were not associated with abnormal ALT (Table 6).

The IL-4-589 CT/CC showed an increased risk, but -589 TT showed a reduced risk of abnormal ALT level. The OR and 95% CI for IL-10-589 CT and -589 CC compared with -589 TT genotype were 3.43 (1.47-8.00) and 8.25 (1.74-39.22), respectively, in patients with abnormal ALT. IL-4-589 C showed an increased risk, but -589 T showed a reduced risk of abnormal ALT level (Table 6). The OR and 95% CI for IL-10-589 C compared with -589 T was 2.31 (1.36-3.93).

The polymorphisms of IL-2-330, IFN-γ+874 and IL-10-1082 were not significantly associated with abnormal ALT (Table 6).

The natural outcome of HBV and HCV infection varies dramatically among individuals. HCV infection is self-limited in a fortunate minority, while the majority of subjects develop persistent (chronic) infection[1,2]. Although infection with HBV in adults progresses to the chronic phase in about 5%[3], among those individuals with persistent HBV or HCV infection, the majority develop CH, progressive fibrosis and even liver cancer[4,5,13]. However, some cases will never progress to any significant liver disease[6,7]. It remains unknown why the infection frequently turns into CH, and why the outcome with HBV and/or HCV infection varies dramatically. Cytokines play a crucial role in regulating the immune and inflammatory responses. Polymorphisms in the regulatory regions of the cytokine genes may influence their expression. Therefore, as genetic predictors of the disease susceptibility or clinical outcome, the polymorphisms of cytokine genes are potentially important.

IL-2 is a Th1 cytokine and has a powerful immunoregulatory effect on the stimulation of proliferation and activation of most T lymphocytes, natural killer cells, and B lymphocytes[14]. Some evidence has shown that the IL-2 levels of patients with moderate/severe CH and cirrhosis are decreased significantly more than those of healthy controls[15-17]. Other authors have observed that increased IL-2 expression is correlated with the grading/staging of chronic hepatitis C[18]. In this study, we found that the IL-2-330 SNP was associated with persistent HBV and/or HCV infection. The subjects with persistent HBV and/or HCV infections had significantly lower IL-2-330 GG genotype frequency and higher IL-2-330 TT genotype frequency than the controls. The subjects with IL-2-330 TT had a 3.46, 7.14 and 2.93 times higher risk of infection with HCV, HBV, or HBV/HCV. The subjects with chronic HCV and/or HBV infections had higher IL-2-330 T allele and lower -330 G allele frequencies, respectively. The patients with the -330 T allele had a 1.82, 2.26 and 1.73 times higher risk of infection with HCV, HBV and HBV/HCV, respectively. At the same time, we also found an association between IL-2-330 SNP and clinical outcome of mild CH, moderate/severe CH and cirrhosis. Compared with the controls, the patients with mild CH, moderate/severe CH and cirrhosis had significantly higher IL-2-330 TT genotype frequency and lower -330 GG genotype frequency. IL-2-330 GG showed a negative correlation with clinical outcome (γ = -0.92, P = 0.01). Individuals with -330 TT genotype had a 3.42, 3.29 and 11.11 times higher risk of developing into mild CH, moderate/severe CH, and cirrhosis, respectively. Subjects with IL-2-330 T had a 1.83, 1.70 and 2.75 times higher risk of developing into mild CH, moderate/severe CH, and cirrhosis, respectively. These results indicate that the IL-2-330 TT genotype and the -330 T allele are not only the potential susceptibility gene for HBV and/or HCV infections, but also the gene that potentially determines clinical outcome. Moreover, the clinical outcome of HBV and/or HCV infection is associated with IL-2 level, as determined by the IL-2-330 polymorphisms. A plausible explanation for the association of IL-2-330 TT genotype and T allele with persistent infection and clinical outcome is derived from experiments that have shown that patients with the IL-2-330 TT genotype and T allele, with lower IL-2 production[5], unsuccessfully eradicate the virus and become persistently viremic, which further results in susceptibility to HBV and/or HCV infection.

IFN-γ is a Th1 cytokine and plays an important role in modulating almost all the immune responses, such as T-cell differentiation, anti-proliferative, antitumor, and antiviral activities[19,20]. Pravica et al[21] have found that IFN-γ+874 T/T genotype is often regarded as indicating high IFN-γ production, and +874 A/A genotype as indicating low production. Some authors have found that plasma IFN-γ concentrations in chronic hepatitis C patients decrease significantly[22,23]. Other authors have documented a correlation between the increase of IFN-γ expression and grading in chronic hepatitis C infection[18,24,25]. In this study, compared with the controls, the IFN-γ+874 AA genotype was found more frequently and the +874 TA genotype was found less frequently in subjects with persistent HBV and/or HCV infection. Subjects with +874 AA genotype have a 3.23, 2.70 and 4.02 times higher risk of HCV infection, HBV infection, and HBV/HCV coinfection, respectively. No difference was found in the IFN-γ+874 T/A alleles among the groups. However, Liu et al[26] have found that the frequency of IFN-γ+874 A allele was significantly higher in patients with chronic HBV infection than in the controls (OR = 2.25, 95% CI = 1.69-2.99, P < 0.0001). Moreover, compared with the controls, the patients with mild CH, moderate/severe CH, and cirrhosis showed a higher IFN-γ+874 AA frequency and a lower IFN-γ+874 TA frequency. Individuals with IFN-γ+874 AA had a 3.09, 3.85 and 3.14 times higher risk of developing mild CH, moderate/severe CH, and cirrhosis, respectively. Compared with moderate/severe CH patients, cirrhosis patients showed a significantly decreased +874 AA genotype frequency. This probably resulted from the lower number of samples of cirrhosis. These results indicate that IFN-γ+874 AA genotype is not only the potential susceptibility gene for HBV and/or HCV infection, but also the gene that potentially determines clinical outcome. A plausible explanation is that IFN-γ+874 AA genotype produces a low level of IFN-γ, which results in the cytolytic defect that promotes viral persistence and hepatic persistent infection that determines the clinical outcome of HBV and/or HCV infection.

IL-10 is an important anti-inflammatory cytokine secreted from Th2 cells. The levels of IL-10 production determine immune regulation, and the balance between the inflammatory and humoral responses. There are three confirmed SNPs in the IL-10 gene promoter. The -1082 GG genotype is associated with high IL-10 production, the -1082 GA with intermediate production, and the -1082 AA with low production. Polymorphisms at position -819 and -592 have no independent influence on IL-10 production[27]. There are contradictory reports about the exact effect of IL-10 promoter polymorphisms on the natural outcome of HBV and HCV infection. Some authors have found that plasma IL-10 level is decreased significantly in chronic hepatitis C patients[22,28]. Others have reported that the level of IL-10 in patients with chronic hepatitis C is higher than that in healthy individuals (P < 0.05). The value of IL-10 showed a significant positive correlation with ALT[29,30]. In the present study, IL-10-1082 AA was associated with an increased risk, but -1082 AG was associated with a reduced risk of persistent HBV and/or HCV infection. Subjects with IL-10-1082 AA had a 2.34, 2.29 and 2.56 times higher risk of persistent HCV infection, HBV infection and HBV/HCV coinfection, respectively. At the same time, IL-10-1082 AA is associated with an increased risk, but -1082 AG is associated with a reduced risk of mild CH, moderate/severe CH, and cirrhosis. Also, IL-10-1082 AA showed a positive correlation with clinical outcome (γ = 0.99, P < 0.01), but -1082 AG showed a negative correlation with clinical outcome (γ = -0.99, P < 0.01). Individuals with the -1082 AA genotype had a 2.03, 2.70 and 4.26 times higher risk of developing mild CH, moderate/severe CH, and cirrhosis, respectively. These results indicate that the IL-10-1082 AA genotype is not only a potential susceptibility gene for HBV and/or HCV infection, but also potentially determines clinical outcome. IL-10-1082 AA and -1082 A were associated with an increased risk, but IL-10-1082 AG and -1082 G were associated with a reduced risk of HCV RNA replication (OR = 3.36, 1.67, respectively). This result indicates that IL-10-1082 AA and -1082 A are associated with HCV RNA replication. The evidence shows that during persistent HCV infection, IL-10 may compromise the cellular immune response to the virus[31-33]. A plausible explanation is that IL-10 is an important anti-inflammatory cytokine. IL-10-1082 AA and -1082 A lead to lower IL-10 production[27] and persistent infection, which determines the clinical outcome of chronic infection. The IL-10-1082 polymorphisms had no significant association with plasma ALT level, which agrees with the results of Abbas et al[34]. The IL-10-592 AC genotype frequency was significantly higher in patients with abnormal ALT (OR = 2.83). This result indicates that the IL-10-592 AC genotype is associated with abnormal ALT level and hepatocellular injury. Hepatocellular injury is probably caused by the decreased production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, which results from linkage of the IL-10-592 and IL-10-1082 genes.

IL-4 is a Th2 cytokine and plays an important role in humoral immunity. IL-4 has the function of inhibiting the production of IFN-γ and downregulating the differentiation of Th1 cells[35]. IL-4 has the function of modulating inflammatory responses by downregulating production of pro-inflammatory mediators and preventing inflammatory injury of the liver[36,37]. It has been described that the IL-4-589 T compared with the -590 C allele increases the strength of the IL-4 promoter[38], which leads to high production of IL-4. The evidence has shown that IL-4 plays a key role in HBV and HCV infection pathogenesis. Some have reported that IL-4 levels are lower in patients infected with HCV[39]. Others have reported that IL-4 is significantly higher in chronic HCV infection with abnormal ALT than with normal ALT level[38,39]. In the present study, IL-4-589 polymorphisms were not significantly associated with persistent HBV and/or HCV infection or clinical outcome. However, we found that the IL-4-589 CT genotype and -589 CC genotype frequency was significantly higher than that of -589 TT genotype frequency in patients with abnormal ALT level. Individuals with IL-4-589 CT and -589 CC genotype had a 3.43 and 8.25 times higher risk of abnormal ALT. Higher -589 C allele and lower -589 T allele frequencies in patients with abnormal ALT were observed; individuals with the -589 C allele had a 2.31 times higher risk of abnormal ALT. This result indicates that the IL-4-589 CC and -589 CT genotype and the -589 C allele are associated with liver inflammatory injury. Such injury is probably caused by the decreased production of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10.

In summary, the polymorphisms of IL-2-330, IFN-γ+874, IL-10-1082 and -592 and IL-4-589 showed a significant association with the outcome of chronic HBV and/or HCV infection. The IL-2-330 TT/T allele, IFN-γ+874 AA and IL-10-1082 AA were associated with increased risk, but IL-2-330 GG/G allele, IFN-γ+874 TA and IL-10-1082 AG were associated with reduced risk of persistent HBV and/or HCV infection, and of developing mild CH, moderate/severe CH, and cirrhosis. The IL-10-1082 AA/A allele was associated with an increased risk, but the IL-10-1082 AG/G allele was associated with a reduced risk of HCV RNA replication. IL-10-592 AC and IL-4-589 CT/CC showed increased risk, but IL-10-592 AA and IL-4-589 TT showed reduced risk of abnormal ALT.

The natural outcome in hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection varies dramatically among individuals. Some infections are self-limited; some individuals progress to persistent HBV or HCV infection; and some develop chronic hepatitis, fibrosis and even liver cancer. The mechanisms are unknown. Besides viral pathogenic factors, a more important factor is the different immune response to HBV or HCV infection between individuals. T helper (Th)1 and Th2 cytokines determine host immunity level, which is regulated by polymorphisms in the promoter region of the Th1 and Th2 cytokines. Interleukin (IL)-2 (-330), interferon (IFN)-γ (+874), IL-10 (-1082, -592), IL-4 (-589) should have some association with the outcome of HBV and/or HCV infection.

It remains unknown why subjects infected with HBV and/or HCV frequently develop chronic infection, and why the outcome of infection varies dramatically. Among infections with HBV/HCV, some show a strong reduction in CD4+ T-helper and CD8+ cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte responses. This is likely to be crucial in clearance of acute viremia. It is thought that immune tolerance to HBV/HCV infection may explain the different susceptibility to HBV/HCV infection. Many manifestations show that the immunity level of the host correlates with relevant gene polymorphisms, especially with single nucleotide polymorphisms in the promoter region, which regulates gene expression. Furthermore, the gene polymorphisms probably determine the outcome of the infection.

The polymorphisms of IL-2-330, IFN-γ+874, IL-10-1082 and -592 and IL-4-589 showed a significant association with the outcome of chronic HBV and/or HCV infection. The IL-2-330 TT/T allele, IFN-γ+874 AA and IL-10-1082 AA were associated with increased risk, but the IL-2-330 GG/G allele, IFN-γ+874 TA and IL-10-1082 AG were associated with reduced risk of persistent HBV and/or HCV infection, and of developing mild chronic hepatitis (CH), moderate/severe CH, and cirrhosis. The IL-10-1082 AA/A allele was associated with increased risk, but the IL-10-1082 AG/G allele was associated with reduced risk of HCV RNA replication. IL-10-592 AC and IL-4-589 CT/CC showed increased risk, but IL-10-592 AA and IL-4-589 TT showed reduced risk of abnormal ALT.

These results suggest that polymorphisms in some cytokine genes influence persistent HBV and/or HCV infection, clinical outcome, HCV replication and liver damage. Some cytokines, including IL-2, IFN-γ and IL-10 might be beneficial to the clinical outcome of HBV and/or HCV infection. Some cytokines, including IL-4, might result in liver damage. These results provide a scientific basis for the further treatment of patients with chronic HBV and HCV infection and viral hepatitis.

IL-2 is a Th1 cytokine and has a powerful immunoregulatory effect on the stimulation of proliferation and activation of most T lymphocytes, natural killer cells, and B lymphocytes. IFN-γ is a Th1 cytokine and plays an important role in modulating almost all the immune responses, such as T-cell differentiation, and anti-proliferative, antitumor, and antiviral activities. IL-10 is an important anti-inflammatory cytokine secreted from Th2 cells. The levels of IL-10 production determine immunoregulation, and the balance between the inflammatory and humoral responses. IL-4 is a Th2 cytokine and plays an important role in humoral immunity. IL-4 has the function of inhibiting the production of IFN-γ and downregulating differentiation of Th1 cells.

This is interesting paper. These results suggest that the IL-10-1082 polymorphisms are associated with Hepatitis C viral replication and the IL-10-592 and IL-4-589 polymorphisms influence liver damage.

Peer reviewer: Seyed-Moayed Alavian, MD, Professor, Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences & Tehran Hepatitis Center, PO Box 14155-3651-Tehran, Iran

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Alter MJ, Margolis HS, Krawczynski K, Judson FN, Mares A, Alexander WJ, Hu PY, Miller JK, Gerber MA, Sampliner RE. The natural history of community-acquired hepatitis C in the United States. The Sentinel Counties Chronic non-A, non-B Hepatitis Study Team. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1899-1905. |

| 2. | Seeff LB. The natural history of chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Liver Dis. 1997;1:587-602. |

| 3. | Vildózola Gonzales H, Salinas JL. [Natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection]. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2009;29:147-157. |

| 4. | Asselah T, Boyer N, Ripault MP, Martinot M, Marcellin P. Management of chronic hepatitis C. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2007;53:9-23. |

| 5. | Hoffmann SC, Stanley EM, Darrin Cox E, Craighead N, DiMercurio BS, Koziol DE, Harlan DM, Kirk AD, Blair PJ. Association of cytokine polymorphic inheritance and in vitro cytokine production in anti-CD3/CD28-stimulated peripheral blood lymphocytes. Transplantation. 2001;72:1444-1450. |

| 6. | Poynard T, Bedossa P, Opolon P. Natural history of liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. The OBSVIRC, METAVIR, CLINIVIR, and DOSVIRC groups. Lancet. 1997;349:825-832. |

| 7. | Kenny-Walsh E. Clinical outcomes after hepatitis C infection from contaminated anti-D immune globulin. Irish Hepatology Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1228-1233. |

| 8. | Diepolder HM, Zachoval R, Hoffmann RM, Jung MC, Gerlach T, Pape GR. The role of hepatitis C virus specific CD4+ T lymphocytes in acute and chronic hepatitis C. J Mol Med. 1996;74:583-588. |

| 9. | Cramp ME, Carucci P, Underhill J, Naoumov NV, Williams R, Donaldson PT. Association between HLA class II genotype and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C viraemia. J Hepatol. 1998;29:207-213. |

| 10. | Knapp S, Hennig BJ, Frodsham AJ, Zhang L, Hellier S, Wright M, Goldin R, Hill AV, Thomas HC, Thursz MR. Interleukin-10 promoter polymorphisms and the outcome of hepatitis C virus infection. Immunogenetics. 2003;55:362-369. |

| 11. | Chen YP, Feng XR, Dai L, Zhang L, Hou JL. Non-invasive diagnostic screening of hepatic fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Chin Med J (Engl). 2004;117:1109-1112. |

| 12. | Chang JJ, Zhang SH, Li L. [Comparing and evaluating six methods of extracting human genomic DNA from whole blood]. Fa Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2009;25:109-111, 114. |

| 13. | Terrault NA, Im K, Boylan R, Bacchetti P, Kleiner DE, Fontana RJ, Hoofnagle JH, Belle SH. Fibrosis progression in African Americans and Caucasian Americans with chronic hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1403-1411. |

| 14. | Seder RA, Paul WE. Acquisition of lymphokine-producing phenotype by CD4+ T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:635-673. |

| 15. | Sakaguchi E, Kayano K, Segawa M, Aoyagi M, Sakaida I, Okita K. [Th1/Th2 imbalance in HCV-related liver cirrhosis]. Nippon Rinsho. 2001;59:1259-1263. |

| 16. | Eckels DD, Tabatabail N, Bian TH, Wang H, Muheisen SS, Rice CM, Yoshizawa K, Gill J. In vitro human Th-cell responses to a recombinant hepatitis C virus antigen: failure in IL-2 production despite proliferation. Hum Immunol. 1999;60:187-199. |

| 17. | Pawlowska M, Halota W, Smukalska E, Grabczewska E. [Serum IL-2 and sIL-2R concentration in children with chronic hepatitis B]. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2005;18:33-35. |

| 18. | Napoli J, Bishop GA, McGuinness PH, Painter DM, McCaughan GW. Progressive liver injury in chronic hepatitis C infection correlates with increased intrahepatic expression of Th1-associated cytokines. Hepatology. 1996;24:759-765. |

| 19. | Belardelli F. Role of interferons and other cytokines in the regulation of the immune response. APMIS. 1995;103:161-179. |

| 20. | Muller U, Steinhoff U, Reis LF, Hemmi S, Pavlovic J, Zinkernagel RM, Aguet M. Functional role of type I and type II interferons in antiviral defense. Science. 1994;264:1918-1921. |

| 21. | Pravica V, Perrey C, Stevens A, Lee JH, Hutchinson IV. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the first intron of the human IFN-gamma gene: absolute correlation with a polymorphic CA microsatellite marker of high IFN-gamma production. Hum Immunol. 2000;61:863-866. |

| 22. | Zhang P, Chen Z, Chen F, Li MW, Fan J, Zhou HM, Liu JH, Huang Z. Expression of IFN-gamma and its receptor alpha in the peripheral blood of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Chin Med J (Engl). 2004;117:79-82. |

| 23. | Osna N, Silonova G, Vilgert N, Hagina E, Kuse V, Giedraitis V, Zvirbliene A, Mauricas M, Sochnev A. Chronic hepatitis C: T-helper1/T-helper2 imbalance could cause virus persistence in peripheral blood. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1997;57:703-710. |

| 24. | Bertoletti A, D’Elios MM, Boni C, De Carli M, Zignego AL, Durazzo M, Missale G, Penna A, Fiaccadori F, Del Prete G. Different cytokine profiles of intraphepatic T cells in chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:193-199. |

| 25. | Paul S, Tabassum S, Islam MN. Interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) response to different hepatitis B virus antigens in hepatitis B virus infection. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 2004;30:71-77. |

| 26. | Liu M, Cao B, Zhang H, Dai Y, Liu X, Xu C. Association of interferon-gamma gene haplotype in the Chinese population with hepatitis B virus infection. Immunogenetics. 2006;58:859-864. |

| 27. | Turner DM, Williams DM, Sankaran D, Lazarus M, Sinnott PJ, Hutchinson IV. An investigation of polymorphism in the interleukin-10 gene promoter. Eur J Immunogenet. 1997;24:1-8. |

| 28. | Gramenzi A, Andreone P, Loggi E, Foschi FG, Cursaro C, Margotti M, Biselli M, Bernardi M. Cytokine profile of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with different outcomes of hepatitis C virus infection. J Viral Hepat. 2005;12:525-530. |

| 29. | Jia HY, Du J, Zhu SH, Ma YJ, Chen HY, Yang BS, Cai HF. The roles of serum IL-18, IL-10, TNF-alpha and sIL-2R in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2002;1:378-382. |

| 30. | Cacciarelli TV, Martinez OM, Gish RG, Villanueva JC, Krams SM. Immunoregulatory cytokines in chronic hepatitis C virus infection: pre- and posttreatment with interferon alfa. Hepatology. 1996;24:6-9. |

| 31. | Eskdale J, Gallagher G, Verweij CL, Keijsers V, Westendorp RG, Huizinga TW. Interleukin 10 secretion in relation to human IL-10 locus haplotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9465-9470. |

| 32. | Edwards-Smith CJ, Jonsson JR, Purdie DM, Bansal A, Shorthouse C, Powell EE. Interleukin-10 promoter polymorphism predicts initial response of chronic hepatitis C to interferon alfa. Hepatology. 1999;30:526-530. |

| 33. | Reuss E, Fimmers R, Kruger A, Becker C, Rittner C, Hohler T. Differential regulation of interleukin-10 production by genetic and environmental factors--a twin study. Genes Immun. 2002;3:407-413. |

| 34. | Abbas Z, Moatter T. Interleukin (IL) 1beta and IL-10 gene polymorphism in chronic hepatitis C patients with normal or elevated alanine aminotransferase levels. J Pak Med Assoc. 2003;53:59-62. |

| 35. | Vercelli D, De Monte L, Monticelli S, Di Bartolo C, Agresti A. To E or not to E? Can an IL-4-induced B cell choose between IgE and IgG4? Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1998;116:1-4. |

| 36. | Kato A, Yoshidome H, Edwards MJ, Lentsch AB. Reduced hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury by IL-4: potential anti-inflammatory role of STAT6. Inflamm Res. 2000;49:275-279. |

| 37. | Yoshidome H, Kato A, Miyazaki M, Edwards MJ, Lentsch AB. IL-13 activates STAT6 and inhibits liver injury induced by ischemia/reperfusion. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1059-1064. |

| 38. | Noguchi E, Nukaga-Nishio Y, Jian Z, Yokouchi Y, Kamioka M, Yamakawa-Kobayashi K, Hamaguchi H, Matsui A, Shibasaki M, Arinami T. Haplotypes of the 5’ region of the IL-4 gene and SNPs in the intergene sequence between the IL-4 and IL-13 genes are associated with atopic asthma. Hum Immunol. 2001;62:1251-1257. |

| 39. | Cribier B, Schmitt C, Rey D, Lang JM, Kirn A, Stoll-Keller F. Production of cytokines in patients infected by hepatitis C virus. J Med Virol. 1998;55:89-91. |