Published online Nov 28, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5586

Revised: September 14, 2009

Accepted: September 21, 2009

Published online: November 28, 2009

AIM: To evaluate the safety of unsedated transnasal small-caliber esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) for elderly and critically ill bedridden patients.

METHODS: One prospective randomized comparative study and one crossover comparative study between transnasal small-caliber EGD and transoral conventional EGD was done (Study 1). For the comparative study, we enrolled 240 elderly patients aged > 65 years old. For the crossover analysis, we enrolled 30 bedridden patients with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) (Study 2). We evaluated cardiopulmonary effects by measuring arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2) and calculating the rate-pressure product (RPP) (pulse rate × systolic blood pressure/100) at baseline, 2 and 5 min after endoscopic intubation in Study 1. To assess the risk for endoscopy-related aspiration pneumonia during EGD, we also measured blood leukocyte counts and serum C-reactive protein (CRP) levels before and 3 d after EGD in Study 2.

RESULTS: In Study 1, we observed significant decreases in SpO2 during conventional transoral EGD, but not during transnasal small-caliber EGD (0.24% vs -0.24% after 2 min, and 0.18% vs -0.29% after 5 min, P = 0.034, P = 0.044). Significant differences of the RPP were not found between conventional transoral and transnasal small-caliber EGD. In Study 2, crossover analysis showed statistically significant increases of the RPP at 2 min after intubation and the end of endoscopy (26.8 and 34.6 vs 3.1 and 15.2, P = 0.044, P = 0.046), and decreases of SpO2 (-0.8% vs -0.1%, P = 0.042) during EGD with transoral conventional in comparison with transnasal small-caliber endoscopy. Thus, for bedridden patients with PEG feeding, who were examined in the supine position, transoral conventional EGD more severely suppressed cardiopulmonary function than transnasal small-caliber EGD. There were also significant increases in the markers of inflammation, blood leukocyte counts and serum CRP values, in bedridden patients after transoral conventional EGD, but not after transnasal small-caliber EGD performed with the patient in the supine position. Leukocyte count increased from 6053 ± 1975/L to 6900 ± 3392/L (P = 0.0008) and CRP values increased from 0.93 ± 0.24 to 2.49 ± 0.91 mg/dL (P = 0.0005) at 3 d after transoral conventional EGD. Aspiration pneumonia, possibly caused by the endoscopic examination, was found subsequently in two of 30 patients after transoral conventional EGD.

CONCLUSION: Transnasal small-caliber EGD is a safer method than transoral conventional EGD in critically ill, bedridden patients who are undergoing PEG feeding.

- Citation: Yuki M, Amano Y, Komazawa Y, Fukuhara H, Shizuku T, Yamamoto S, Kinoshita Y. Unsedated transnasal small-caliber esophagogastroduodenoscopy in elderly and bedridden patients. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(44): 5586-5591

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i44/5586.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.5586

Small-caliber endoscopy of the upper gastrointestinal tract was developed and for transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and has been used frequently in the past decade[1-4]. Transnasal small-caliber EGD has improved the safety of the endoscopic examination, and has fewer adverse effects on cardiopulmonary function[5-10] and autonomic nerve function[11], compared with transoral conventional EGD. Transnasal small-caliber EGD provides good operability compared to that of transoral conventional EGD[12], and requires no special training[13]. For these reasons, unsedated transnasal small-caliber EGD is used routinely in endoscopic examinations of the upper gastrointestinal tract, often in preference to transoral conventional EGD.

Although we perform endoscopy on elderly and critically ill patients with increasing frequency, we have little information concerning the relative safety of transnasal small-caliber and transoral conventional EGD in these patient groups. Elderly patients do not frequently gag or choke during transoral conventional EGD. If transoral conventional EGD is safe and comfortable for the elderly, the value of transnasal small-caliber EGD is limited, since the smaller charge-coupled device in the endoscope may potentially reduce diagnostic accuracy for minute gastric lesions. The comparative safety of the two techniques should therefore be considered carefully for the treatment of elderly patients with higher risks for gastric cancer and cardiopulmonary diseases.

We compared the safety and tolerability of transnasal and transoral EGD in patients aged > 65 years old and in chronically bedridden elderly patients who required percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) feeding. We used a prospective comparative study and a crossover analysis to evaluate changes in hemodynamic and pulmonary function, and the risk of endoscopy-related aspiration pneumonia during EGD by each method.

These following prospective and crossover studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of Izumo City General Medical Center. In Study 1, we obtained written informed consent from all the participants. In Study 2, written informed consent was obtained from the key family members of the enrolled patients.

We compared changes in cardiopulmonary function during unsedated transnasal small-caliber and transoral conventional EGD in patients aged > 65 years old.

Patients: Between July 2006 and April 2007, we enrolled 240 elderly patients (> 65 years old), who received EGD for their abdominal symptoms and for their annual medical check in the Izumo City General Medical Center, into the prospective comparison study. The first consecutive 120 patients were assigned to the transnasal small-caliber EGD (TN) group and the second consecutive 120 patients to the transoral conventional EGD (TO) group.

Endoscopic procedure: A single experienced endoscopist (M.Y.), certified by the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society, performed all of the examinations. Patients in the TN group were examined with a small-caliber videoendoscope (EG-530N; Fujinon Toshiba ES Systems Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), 5.9 mm in diameter. Patients in the TO group were examined with a conventional endoscope (GIF-H260; Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan), 9.8 mm in diameter. Patients who needed endoscopic biopsy and/or received a time-consuming chromoendoscopic examination were excluded from this study.

Patients in the TO group received throat anesthesia by application of 5 mL 2% lidocaine viscous (Xylocaine viscous; Astra Zeneca, Osaka, Japan) for 5 min. Nasal anesthesia was started in patients in the TN group by spraying a solution of 0.4% lidocaine and 0.5% naphazoline into the nostril. The patients were then instructed to inhale 2% lidocaine jelly (Xylocaine jelly; Astra Zeneca), and a 20 Fr catheter covered with lidocaine jelly was inserted into the deeper nasal cavity for 5 min. All the EGDs were performed with the patient in the left lateral recumbent position, and without administration of scopolamine butylbromide.

Cardiopulmonary monitoring: Systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP), pulse rate (PR), and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry (SpO2) were measured at the following four points during the endoscopic examination, to measure these parameters at the stabilized condition of patients: (1) baseline; (2) at 2 min and (3) at 5 min after endoscopic intubation; and (4) at the end of the examination. The values of BP, PR and SpO2 were measured simultaneously with high sensitivity by the newly developed measuring system, Bedside Monitor PetiTelemo DS-7001 (Fukuda Denshi Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The rate-pressure product (PR × systolic BP/100) was also calculated as shown in previous reports[14,15]. Changes in each value were compared between TN and TO groups.

In the patients treated with PEG tube feeding, we performed periodic PEG tube exchanges during endoscopic observation every 6 mo. For these observations, an endoscopic method, transoral conventional or transnasal small-caliber was selected randomly for each patient by an envelop method, and switched at the next exchange (a crossover design). Changes in cardiopulmonary parameters and markers of inflammation were measured during EGD, and blood leukocyte counts and serum C-reactive protein (CRP) concentrations were measured before and after EGD.

Patients: Between March 2007 and April 2008, 30 patients who were undergoing PEG feeding were enrolled. Reasons for PEG feeding included dysphagia caused by cerebral infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and other conditions. Their PEG tube exchanges were carried out routinely under endoscopic observation every 6 mo, using an instrument (transnasal small-caliber or transoral conventional endoscope) that was assigned randomly to each patient at enrollment. At the next tube exchange 6 mo later, the alternate method was used for each patient. The 30 patients were thereby divided into one initially transnasal, secondarily transoral (TN-TO, n = 15) group, and one initially transoral, secondarily transnasal (TO-TN, n = 15) group. In all of the enrolled patients, a bumper type kit (Ponsky Non-Balloon Replacement Gastrostomy Tube; Bard Limited, Salt Lake City, UT, USA) was used as a PEG tube. Each procedure for the PEG tube exchanges was not done when the patients had infectious diseases such as pneumonia, or urinary or hepato-biliary tract infection. Before PEG tube exchange, chest X-ray examination, urinalysis, and laboratory blood tests including peripheral blood count, inflammatory markers and hepato-biliary enzymes were done to confirm the absence of infectious diseases. In this study, PEG tube exchanges were not performed in patients who showed increases of leukocyte count or CRP and fever elevation before the procedure.

Endoscopic procedure: A single experienced endoscopist (M.Y., as in Study 1) performed all of the examinations, using the same endoscopes and pre-medication regimens as in Study 1. The procedure for PEG tube exchange by transnasal endoscope was similar to that by transoral endoscope. All the EGDs were performed with the patient in the supine position, and without administration of scopolamine butylbromide.

Cardiopulmonary monitoring: During each endoscopy procedure, systolic and diastolic BP, PR, SpO2 and RPP were determined at the following three points: (1) baseline; (2) at 2 min after endoscopic intubation; and (3) at the end of the examination. Changes in each value were compared between TN and TO endoscopic studies.

Evaluation of inflammatory response: As markers of inflammation, body temperature, leukocyte counts and serum concentrations of CRP were measured. Body temperature was measured before and every 6 h after the endoscopy-guided exchange of PEG tube. Leukocyte counts and CRP were performed routinely before and 3 d after the procedure. If suspicious pneumonia was found, these parameters were examined more frequently. Further examination of pneumonia such as chest X-ray examination and/or computed tomography (CT) was done when respiratory symptoms, fever elevation, and increased leukocyte count and/or CRP were found.

Increased occurrence of aspiration pneumonia: The incidence of aspiration pneumonia was also compared between the TN and TO groups. Pulmonary aspiration was defined by witnessed aspiration or tracheal suctioning of secretions including saliva as shown by previous studies on PEG procedures[16,17]. In patients with post-procedure elevation of inflammation markers and/or fever, aspiration pneumonia was evaluated by chest X-ray examination and/or CT. Pneumonia was diagnosed by the presence of new infiltrates of the lung associated with fever.

Data for each comparison between groups were analyzed using the χ2 and Wilcoxon signed rank tests. The latter test was done only when the Friedman test showed significant differences. Categorical data were compared using Student’s t test or, where unequal variances occurred, Welch’s test. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 12.0 (SPSS Japan, Tokyo, Japan).

Ninety-six and 102 elderly patients were analyzed finally as the TN and TO groups, respectively. Twenty-four and 18 patients were excluded since complete data could not be obtained, mainly because of the delay in measurement in the TN and TO groups, respectively. Characteristics of the enrolled patients in each group are shown in Table 1. Mean ages of these patients were 77.0 and 76.7 years, respectively. Total procedure time for EGD was 8.46 ± 4.32 min in the TN group, and 6.03 ± 2.50 min in the TO group. This difference in procedure time was statistically significant (P < 0.001). No serious complications in cardiopulmonary function occurred in this study, although two patients experienced mild epistaxis during pre-medication for transnasal EGD. The baseline cardiopulmonary parameters, RPP and SpO2, did not show any significant differences (Table 1).

| TN group | TO group | P value | |

| Age (range, yr) | 77.0 ± 7.7 (65-97) | 76.7 ± 7.2 (65-95) | NS |

| Gender (M:F) | 30:66 | 53:49 | NS |

| Total procedure time (min) | 8.46 ± 4.32 | 6.03 ± 2.50 | 0.001 |

| Baseline cardiopulmonary parameters | |||

| Systolic BP | 131.4 ± 19.3 | 135.4 ± 21.8 | NS |

| Diastolic BP | 67.6 ± 12.3 | 70.5 ± 12.8 | NS |

| RPP | 100.2 ± 27.4 | 98.82 ± 25.7 | NS |

| SpO2 | 98.1 ± 1.4 | 98.2 ± 1.4 | NS |

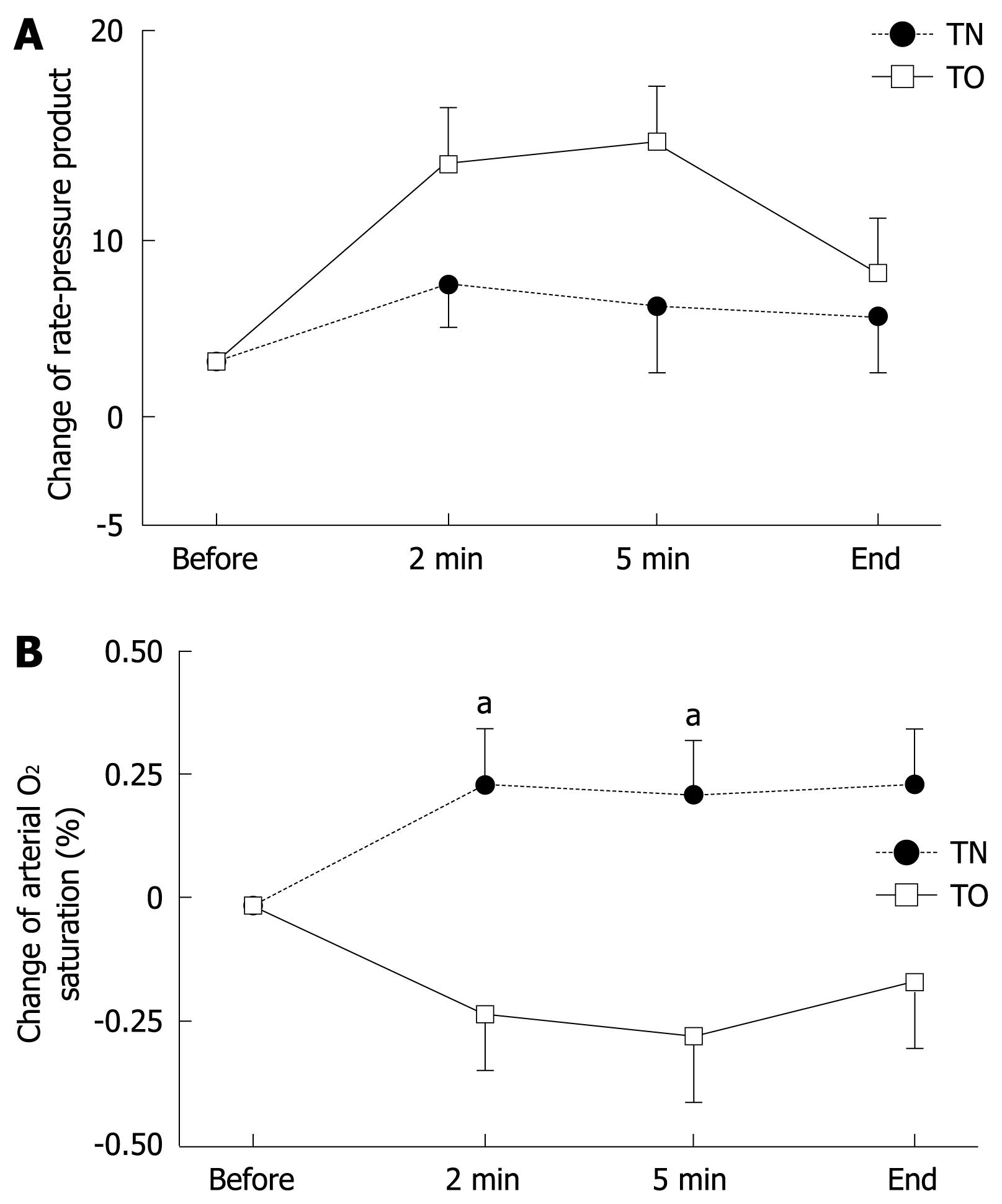

Changes in BP, PR and RPP during endoscopy did not differ significantly between the TN and TO groups, although these parameters tended to increase more in the TO group (Figure 1A). Values for SpO2 in the TO group decreased significantly during EGD (-0.24% and -0.29% after 2 and 5 min) compared with those in the TN group (+0.24% and +0.18% after 2 and 5 min, P < 0.05). These findings suggested that transoral EGD affects pulmonary function more severely than transnasal EGD does in this group of patients (Figure 1B).

We enrolled 30 patients who required PEG feeding: 15 in the TN-TO group and 15 in the TO-TN group. Characteristics of these patients are shown in Tables 2 and 3. Categorical data did not differ significantly between the TN-TO and TO-TN groups. Baseline cardiopulmonary parameters, RPP and SpO2, did not differ significantly.

| TN-TO group | TO-TN group | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 84.3 ± 7.9 | 80.7 ± 15.8 | NS |

| Gender (M:F) | 3:12 | 4:11 | NS |

| Background pathological condition for PEG feeding | |||

| Cerebral infarction | 10 | 11 | |

| Cerebral hemorrhage | 2 | 3 | |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 1 | 0 | |

| Others | 2 | 1 |

| TN-EGD | TO-EGD | P value | |

| Total procedure time (min) | 4.36 ± 3.46 | 4.42 ± 3.18 | NS |

| Baseline cardiopulmonary parameter | |||

| Systolic BP | 125.5 ± 25.3 | 122.6 ± 28.4 | NS |

| Diastolic BP | 70.1 ± 17.8 | 64.9 ± 20.1 | NS |

| RPP | 107.7 ± 44.6 | 101.3 ± 37.9 | NS |

| SpO2 | 98.7 ± 1.7 | 95.4 ± 17.5 | NS |

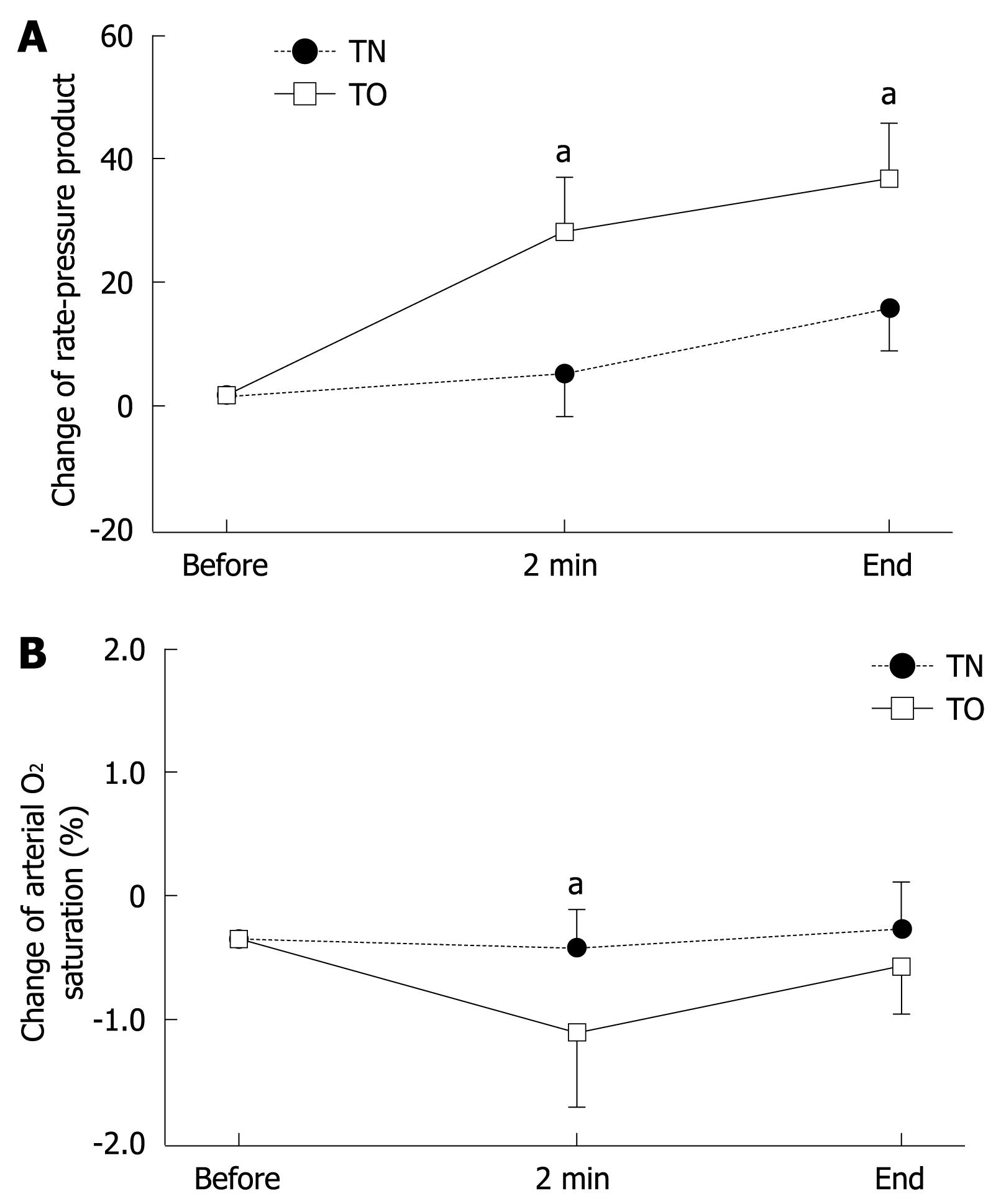

Higher values of systolic and diastolic BP were found in the TO group than in the TN group after intubation for endoscopy, but these differences did not reach statistical significance. Values for RPP during and at the end of endoscopy were significantly higher in the TO group (26.8 and 34.6) than those in the TN group (3.1 and 15.2, P < 0.05), as shown in Figure 2A. The SpO2 also significantly decreased at 2 min after the start of transoral EGD (-0.8%) in comparison with transnasal EGD (-0.1%, P < 0.05) (Figure 2B). Thus, in the bedridden patients with PEG feeding, examined in the supine position, transoral EGD disturbed cardiopulmonary function more strongly than did transnasal EGD.

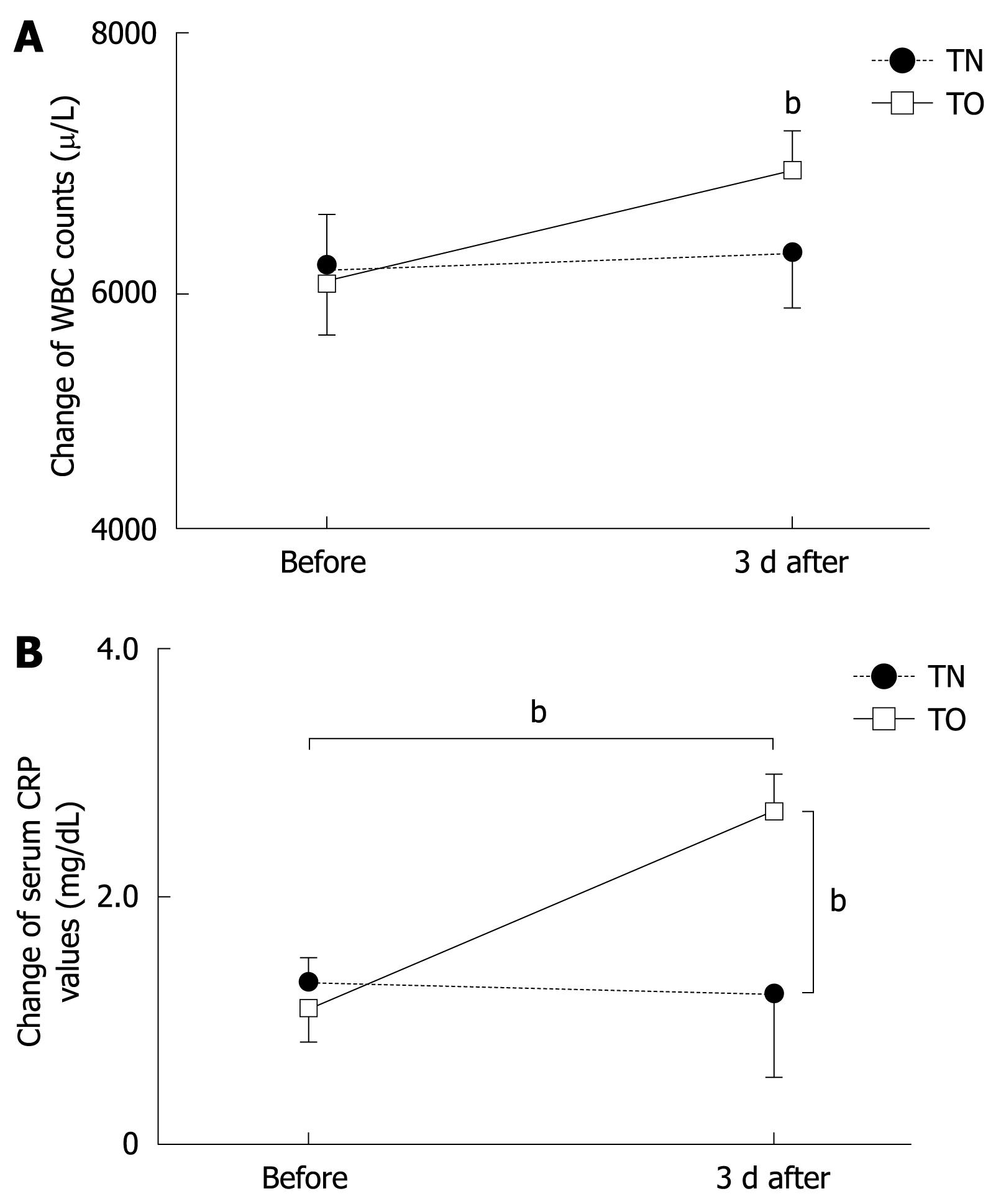

Markers of inflammation also changed significantly in conjunction with endoscopy. Peripheral leukocyte count increased from 6053 ± 1975/L to 6900 ± 3392/L at 3 d after transoral EGD, as shown in Figure 3A (P < 0.001); and CRP values increased from 0.93 ± 0.24 mg/dL to 2.49 ± 0.91 mg/dL (P < 0.001) (Figure 3B). These data also showed statistically significant differences at 3 d after PEG tube exchange between transnasal and transoral EGD (P < 0.001).

Aspiration pneumonia, possibly caused by the endoscopic examination, was subsequently found in two of 30 patients after transoral EGD. In these two cases, a significant drop in SpO2 values was found during transoral EGD, and the elevation of inflammation makers (CRP values and leukocyte counts) was also found after the procedure with transoral EGD but not with transnasal EGD. Additionally, the witnessed aspiration or tracheal suctioning of secretions including saliva was observed in these two cases of transoral EGD. Both of these patients recovered after the administration of antibiotics.

Transnasal small-caliber endoscopy, recently accepted for screening of the upper gastrointestinal tract, presents advantages apart from image quality, a noteworthy feature of transoral conventional endoscopy. Unsedated transoral EGD is well known to increase BP and PR, with an increased cardiopulmonary work load[2,4-6]. Recently, small-caliber endoscopes have been developed and used for EGD with the transnasal route. Several investigators have demonstrated that transnasal EGD with small-caliber endoscopes is feasible and tolerable[7-11], since transnasal small-caliber EDG is less stimulative to the uvula, palatine arches and posterior part of the tongue, and does not induce gag reflex[6]. Therefore, the feasibility and tolerability of unsedated transnasal small-caliber EGD strongly support its value as a standard screening procedure. However, the studies on transnasal small-caliber EGD were done mainly on relatively young patients aged < 60 years old. Elderly patients are believed to tolerate easily transoral EGD without excessive gagging or choking. Therefore, the clinical advantage of transnasal small-caliber EGD for this population may not outweigh the advantage of higher image quality obtained with conventional EGD. To determine the value of the transnasal small-caliber endoscope for screening older patients, we must first establish its tolerability and safety for this group. We have found no studies that specifically have addressed this issue.

In the first part of our study, we found no significant difference between transnasal and transoral endoscopy with respect to hemodynamic parameters. On the other hand, SpO2, a measure of pulmonary function, significantly declined during transoral endoscopy, although the decrease was small. The small decrease in SpO2 is not clinically important for elderly patients in good physical condition. However, for elderly patients with cardiopulmonary diseases and resulting decreased basal SpO2 value, further small decreases in SpO2 are prone to have serious consequences. Patients long confined to bed (including most who require PEG feeding) may become susceptible to infectious pulmonary diseases as a result of swallowing disturbance or micro-aspiration that accompanies decreased SpO2. For safety in the periodic tube exchange, endoscopy-guided re-intubation of the PEG kit is recommended for these patients, because wrong replacement of the feeding tube can cause serious complications, such as peritonitis. This procedure requires that the patient remains supine, which increases the risk for aspiration of saliva and refluxed gastric contents. Transoral endoscopy may stimulate salivary secretion and thereby increase the risk of aspiration pneumonia. In addition, the supine position may influence specifically hemodynamic and/or pulmonary parameters during endoscopy. Previous studies have assessed only the hemodynamic changes that occur when PEG tube insertion is monitored with transnasal small-caliber endoscopy[18,19]. We have therefore measured pulmonary function and two markers of inflammation, as well as hemodynamic parameters, in this endoscopic examination (i.e. with the patient in the supine position). We consistently found advantages in the use of the transnasal small-caliber endoscope, with respect to both hemodynamic and pulmonary parameters. Significant increases in leukocyte counts and CRP values, which indicate systemic inflammatory disease, occurred only after transoral conventional endoscopy. Aspiration pneumonia was found in two cases after 30 transoral endoscopic procedures for the replacement of the PEG tube. PEG tube exchange is done in the supine position, therefore, the patients may have a higher risk of aspiration. However, no pneumonia was found after the procedure using the transnasal small-caliber endoscope. The transoral conventional endoscope may stimulate salivary secretion and further increase the risk of aspiration. Additionally, the oral cavity and saliva of bedridden patients with PEG feeding is prone to be infected by bacteria that may cause pneumonia. Use of the transnasal small-caliber endoscope may therefore reduce the risk of this potentially serious complication of transoral conventional EGD in bedridden patients.

In conclusion, SpO2 decreased significantly in elderly patients during transoral conventional EGD, but not during transnasal small-caliber EGD. Compared to transoral conventional EGD, transnasal small-caliber endoscopy may reduce the risk of aspiration pneumonia, when the patient must be examined in the supine position. Therefore, transnasal small-caliber EGD is a safer method than transoral conventional EGD in critically ill patients, such as those who are bedridden and undergoing PEG feeding.

Unsedated transnasal small-caliber esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is often used to examine the upper gastrointestinal tract. Its efficacy for elderly and critically ill patients, however, has not been fully evaluated. To evaluate the tolerability of transnasal EGD for elderly and critically ill bedridden patients, a prospective randomized comparative and a crossover study were undertaken.

Elderly patients, including those who are bedridden, do not frequently gag or choke during transoral conventional EGD. If transoral conventional EGD is safe and comfortable for them, the value of transnasal small-caliber EGD could be limited, because the smaller charge-coupled device in the endoscope may potentially reduce diagnostic accuracy for minute gastric lesions. This is believed to be the first published study concerned with the tolerability and safety of transnasal small-caliber endoscopy for critically ill patients.

Other studies evaluating the tolerability and safety of transnasal endoscopy have focused mainly on younger patients, with a mean age < 50 years old. The data and viewpoints originated from elderly and critically ill patients and have not been published elsewhere.

Significant decreases were observed in SpO2 saturation during conventional transoral EGD, but not during transnasal small-caliber EGD. Significant increases were also found in the markers of inflammation in bedridden patients after transoral conventional EGD, but not after transnasal small-caliber EGD performed with the patient in the supine position.

This is a prospective study that compared the consequences of using two endoscopic devices (conventional and small caliber) in critically ill patients. The importance of this study is related to the fact that the use of small caliber endoscopes in diagnosis is becoming more common because of its tolerability and lack of sedation.

Peer reviewers: Javier San Martín, Chief, Gastroenterology and Endoscopy, Sanatorio Cantegril, Av. Roosevelt y P 13, Punta del Este 20100, Uruguay; Dr. Grigoriy E Gurvits, Department of Gastroenterology, St. Vincent’s Medical Center, 170 West 12th Street, New York, NY 10011, United States

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Dumortier J, Ponchon T, Scoazec JY, Moulinier B, Zarka F, Paliard P, Lambert R. Prospective evaluation of transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy: feasibility and study on performance and tolerance. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:285-291. |

| 2. | Garcia RT, Cello JP, Nguyen MH, Rogers SJ, Rodas A, Trinh HN, Stollman NH, Schlueck G, McQuaid KR. Unsedated ultrathin EGD is well accepted when compared with conventional sedated EGD: a multicenter randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1606-1612. |

| 3. | Dumortier J, Napoleon B, Hedelius F, Pellissier PE, Leprince E, Pujol B, Ponchon T. Unsedated transnasal EGD in daily practice: results with 1100 consecutive patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:198-204. |

| 4. | Murata A, Akahoshi K, Sumida Y, Yamamoto H, Nakamura K, Nawata H. Prospective randomized trial of transnasal versus peroral endoscopy using an ultrathin videoendoscope in unsedated patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:482-485. |

| 5. | Preiss C, Charton JP, Schumacher B, Neuhaus H. A randomized trial of unsedated transnasal small-caliber esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) versus peroral small-caliber EGD versus conventional EGD. Endoscopy. 2003;35:641-646. |

| 6. | Yagi J, Adachi K, Arima N, Tanaka S, Ose T, Azumi T, Sasaki H, Sato M, Kinoshita Y. A prospective randomized comparative study on the safety and tolerability of transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Endoscopy. 2005;37:1226-1231. |

| 7. | Trevisani L, Cifalà V, Sartori S, Gilli G, Matarese G, Abbasciano V. Unsedated ultrathin upper endoscopy is better than conventional endoscopy in routine outpatient gastroenterology practice: a randomized trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:906-911. |

| 8. | Kawai T, Miyazaki I, Yagi K, Kataoka M, Kawakami K, Yamagishi T, Sofuni A, Itoi T, Moriyasu F, Osaka Y. Comparison of the effects on cardiopulmonary function of ultrathin transnasal versus normal diameter transoral esophagogastroduodenoscopy in Japan. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:770-774. |

| 9. | Thota PN, Zuccaro G Jr, Vargo JJ 2nd, Conwell DL, Dumot JA, Xu M. A randomized prospective trial comparing unsedated esophagoscopy via transnasal and transoral routes using a 4-mm video endoscope with conventional endoscopy with sedation. Endoscopy. 2005;37:559-565. |

| 10. | Alami RS, Schuster R, Friedland S, Curet MJ, Wren SM, Soetikno R, Morton JM, Safadi BY. Transnasal small-caliber esophagogastroduodenoscopy for preoperative evaluation of the high-risk morbidly obese patient. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:758-760. |

| 11. | Mori A, Ohashi N, Tatebe H, Maruyama T, Inoue H, Takegoshi S, Kato T, Okuno M. Autonomic nervous function in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: a prospective randomized comparison between transnasal and oral procedures. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:38-44. |

| 12. | Dumortier J, Josso C, Roman S, Fumex F, Lepilliez V, Prost B, Lot M, Guillaud O, Petit-Laurent F, Lapalus MG. Prospective evaluation of a new ultrathin one-plane bending videoendoscope for transnasal EGD: a comparative study on performance and tolerance. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:13-19. |

| 13. | Maffei M, Dumortier J, Dumonceau JM. Self-training in unsedated transnasal EGD by endoscopists competent in standard peroral EGD: prospective assessment of the learning curve. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:410-418. |

| 14. | Robinson BF. Relation of heart rate and systolic blood pressure to the onset of pain in angina pectoris. Circulation. 1967;35:1073-1083. |

| 15. | Gobel FL, Norstrom LA, Nelson RR, Jorgensen CR, Wang Y. The rate-pressure product as an index of myocardial oxygen consumption during exercise in patients with angina pectoris. Circulation. 1978;57:549-556. |

| 16. | Carnes ML, Sabol DA, DeLegge M. Does the presence of esophagitis prior to PEG placement increase the risk for aspiration pneumonia? Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:1798-1802. |

| 17. | Kitamura T, Nakase H, Iizuka H. Risk factors for aspiration pneumonia after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Gerontology. 2007;53:224-227. |

| 18. | Lustberg AM, Darwin PE. A pilot study of transnasal percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1273-1274. |

| 19. | Dumortier J, Lapalus MG, Pereira A, Lagarrigue JP, Chavaillon A, Ponchon T. Unsedated transnasal PEG placement. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:54-57. |