Published online Nov 14, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5368

Revised: October 12, 2009

Accepted: October 19, 2009

Published online: November 14, 2009

Essential thrombocythemia is frequently associated with abdominal thrombotic complications including portal cavernoma as a consequence of chronic portal vein thrombosis. Essential thrombocythemia in a latent form is difficult to identify at onset due to the absence of an overt disease phenotype. In the presented case report, the diagnosis of essential thrombocythemia was initially missed because the typical disease phenotype was masked by bleeding and hypersplenism. The correct diagnosis was only reached when the patient experienced persistent thrombocytosis and pseudohyperkalemia after a shunt operation.

- Citation: Cai XY, Zhou W, Hong DF, Cai XJ. A latent form of essential thrombocythemia presenting as portal cavernoma. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(42): 5368-5370

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i42/5368.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.5368

Portal cavernoma is the consequence of persistent portal vein thrombosis (PVT) which may be caused by a variety of conditions including cirrhosis, cancer, abdominal infectious disease and myeloproliferative disorders (MPD). Its related symptoms are gastrointestinal bleeding, splenomegaly and hypersplenism as a consequence of portal hypertension.

Essential thrombocythemia (ET) is the most prevalent MPD. It is characterized by persistent thrombocytosis with an estimated annual incidence between 0.77 and 2.53 per 100 000 population, and is relatively common in young females. The predominant clinical features are thrombosis and hemorrhage, as well as delayed occurrence of transformation into leukemia or other myeloid diseases[1]. We describe here a young woman suffering from portal cavernoma caused by latent ET, which was masked by bleeding and hypersplenism. The correct diagnosis was only reached when she experienced persistent thrombocytosis and pseudohyperkalemia after a shunt operation.

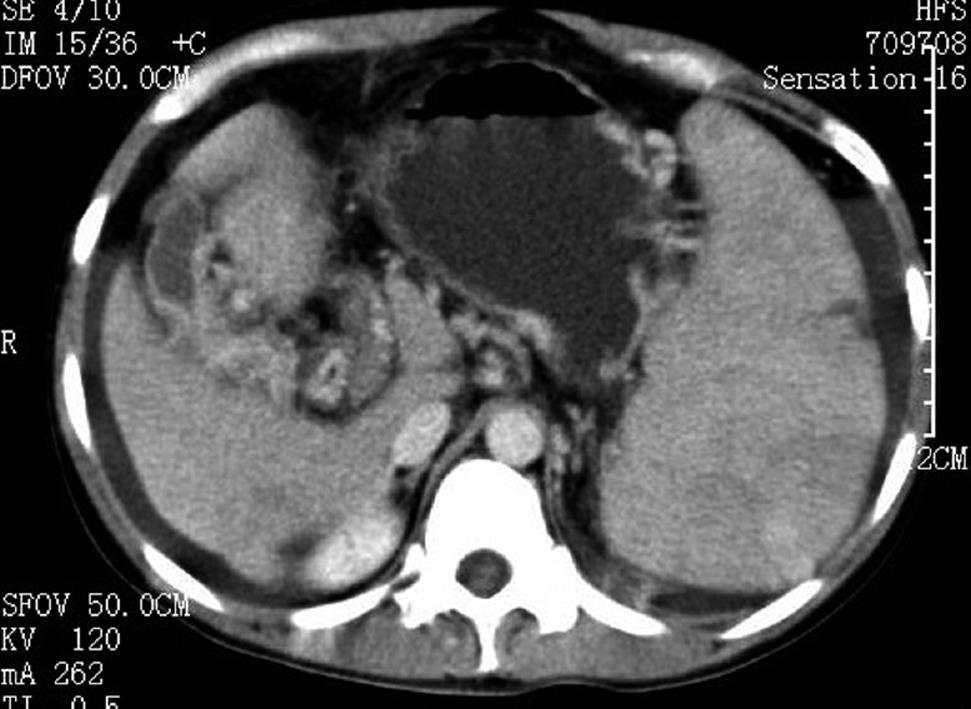

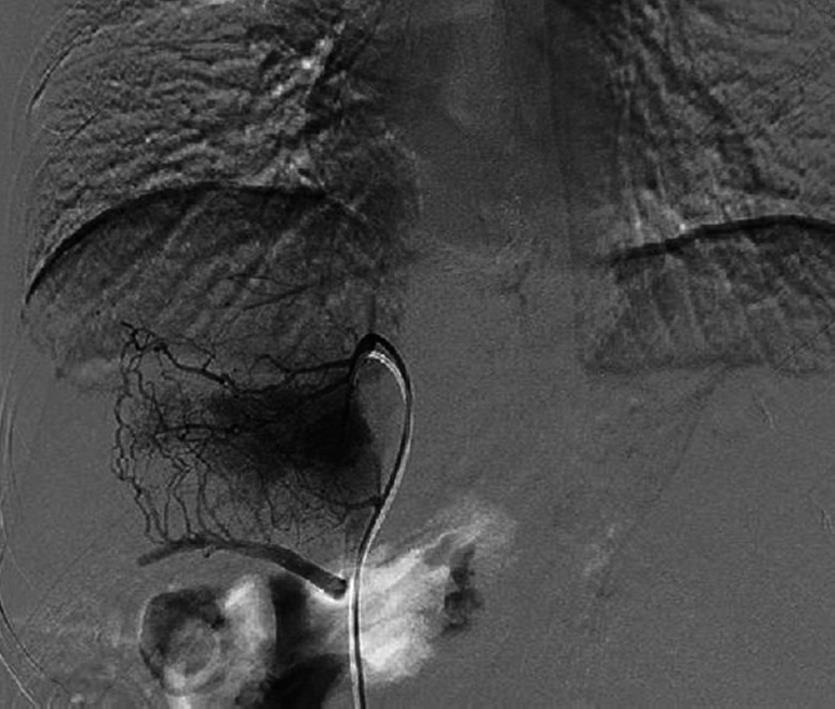

A 36-year-old female was admitted for recurrent upper quadrant abdominal pain of one year and violent hematemesis two days before. She was found to have a low hemoglobin level, and received a transfusion in a local hospital. Physical examination revealed a non-tender and firm spleen with degree III enlargement. The patient denied the use of contraceptive agents and a history of vascular thrombosis. Laboratory investigations revealed a hemoglobin of 71 g/L, hematocrit of 26.8%, leukocyte count of 12.4 × 109/L, and a platelet count of 313 × 109/L. Viral hepatitis serology was negative. A slightly prolonged prothrombin time of 17.2/13.5 s and a partial thromboplastin time of 43.8/36.5 s were noted during coagulation screening. Liver and renal functions were within normal range. Computed tomography scan showed splenomegaly and varicose veins in the esophagus and gastric fundus (Figure 1). Portovenography showed non-visualization of the portal vein and splenic vein with the formation of lots of collaterals, confirming the presence of portal cavernoma (Figure 2).

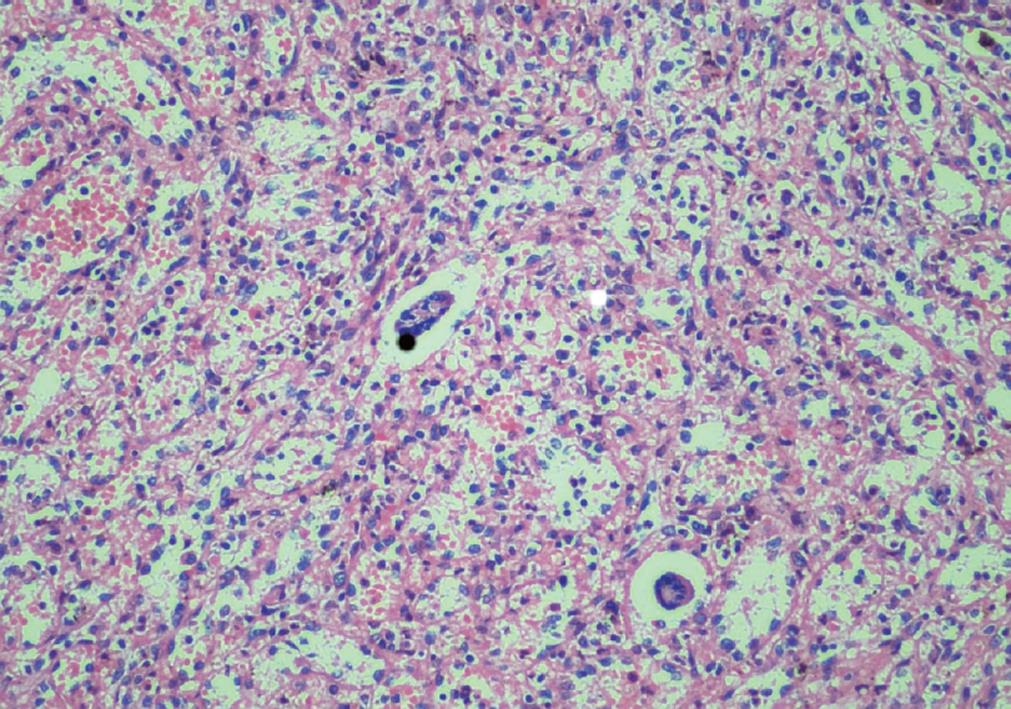

Obvious cavernous transformation was found at the porta hepatis during surgery. Splenectomy and a mesocaval interposition shunt with prosthetic H-graft were performed. Pathological study of the spleen showed chronic congestion and extramedullary hemopoiesis (Figure 3). The patient received antithrombotic treatment with low-dose heparin immediately after surgery. When the platelet count progressively increased to 1137 × 109/L two weeks later, the patient was administered aspirin tablets 100 mg/d.

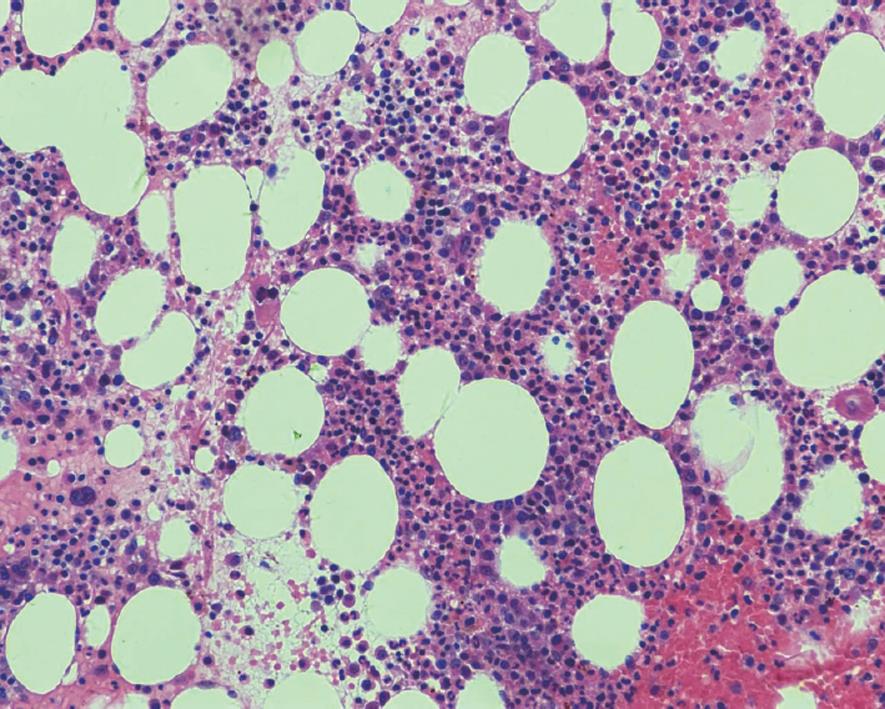

On postoperative day 18, routine laboratory investigations revealed hyperkalemia of 6.1 mmol/L, hemoglobin of 10.3 g/L, leukocyte count of 14.7 × 109/L, and platelet count of 1551 × 109/L. She denied any complaints and electrocardiogram was normal. Hyperkalemia repeatedly occurred despite the use of exchange resin and insulin. Pseudohyperkalemia was suspected after all the causes of hyperkalemia were excluded through detailed examination. Plasma potassium concentration was found to be within the normal range, while the serum concentration remained high. The diagnosis of pseudohyperkalemia was confirmed and the medical treatment for hyperkalemia was stopped. One month after surgery, the platelet count reached 2246 × 109/L. A hematology consultation was obtained to perform a bone marrow biopsy, which signified megakaryocytic hyperplasia (Figure 4) and negative Bcr/abl confluence gene. The diagnosis of essential thrombocythemia was established and the patient was started on hydroxyurea therapy under close hematological monitoring. After discharge from hospital, she was asymptomatic, and the platelet count decreased to 629 × 109/L within three months of surgery.

Cavernous transformation of portal vein refers to the development of a network of tortuous collateral vessels bypassing the obstructive area due to chronic PVT. Once the liver blood supply decreases significantly, the compensatory mechanism is activated and collaterals begin to form within a few days of the obstruction and organize into a cavernomatous transformation in 3-5 wk. Symptom development is often insidious and related to the progression of portal hypertension. Cirrhosis and cancer are common causes in adults. Other possible etiological factors include abdominal surgery and trauma, pancreatic disease, splanchnic infection, other hypercoagulability associated disease, and the use of oral contraceptive medicines. Ogren et al[2] studied 23 796 autopsies in Sweden and found the population prevalence of PVT was 1.0%. They reported that 28% of PVT patients had cirrhosis, 23% primary and 44% secondary hepatobiliary malignancy, 10% major abdominal infectious or inflammatory disease and 3% had a myeloproliferative disorder. MPD with a combination of several prothrombotic factors constitute the most common identifiable causes among non-cirrhotic and non-tumoral PVT cases in the West with an estimated prevalence of 30%-60%[3,4].

ET is frequently associated with thrombotic complications in the large abdominal vessels. Gangat et al[5] reported a prevalence rate of 4% for abdominal vein thrombosis in 460 consecutive patients with ET, but did not provide detailed information on portal vein thrombosis. The risk factors for thrombosis in ET patients include age, thrombotic history, cardiovascular risk factors and genetic or acquired thrombophilia[6]. It seems likely that elevated platelet counts are implicated in thrombotic events in ET, however, the degree of elevation does not appear to be important. It is well documented that thrombosis may occur at relatively low platelet counts[7]. ET usually carries the best prognosis among the MPD, but abdominal vein thrombosis was identified as a risk factor for poor survival and appeared to be the result of excess death from leukemic or fibrotic transformation and hepatic failure[5].

Treatment options for ET include aspirin (or an equivalent therapy) and cytoreductive therapy to control the platelet count such as hydroxyurea, anagrelide and interferon, however, there is still a lot of controversy regarding the role of anticoagulation in patients with chronic PVT. The management of bleeding varices due to MPD is not different from cirrhotic or cancer patients, but the prognosis is unquestionably better in the former cases[8]. It seems that the mortality rate from variceal bleeding in patients without liver disease is primarily related to underlying diseases other than bleeding itself[9].

In our case, the diagnosis of cavernous transformation was definite on admission. MPD was not considered because the platelet count was only slightly elevated. After splenectomy, the platelet count increased very quickly, and even exceeded 2000 × 109/L. This suggested that the features of ET in peripheral blood cell counts are masked by hypersplenism. For patients with extreme thrombocytosis, active research is important to exclude latent MPD, although reactive thrombocytosis is usually a more common cause than ET. Recently the discovery of a mutation in V617F of the Janus Kinase 2 gene in a significant proportion of ET patients provides a new strategy for molecular diagnosis[7].

For patients with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension, in particular with extrahepatic portal vein thrombosis, portosystemic shunt surgery provides efficient and permanent decompression of the portal venous system without liver function deterioration or encephalopathy. Several authors have advocated preserving the spleen whenever possible especially in MPD, because the spleen may become a place for extramedullary marrow formation[9]. During surgery, we planned to perform a spleen-preserving splenorenal side-to-side shunt, but failed to find normal splenic veins, so converted to splenectomy and a mesocaval interposition (H-graft) shunt.

In the present case, the patient developed elevated serum potassium of 6.1 mmol/L with extreme thrombocytosis of 1551 × 109/L on postoperative day 18. Active research failed to find a cause of hyperkalemia, therefore pseudohyperkalemia was suspected and plasma potassium level was measured to confirm the diagnosis. The phenomenon of pseudohyperkalemia was first reported in 1955, and has been commonly observed in patients with severe thrombocytosis, erythrocytosis and the presence of activated platelets[10]. It is characterized by a marked elevation of serum potassium concentration with normal plasma potassium level. Patients with pseudohyperkalemia are usually without any clinical manifestation of electrolyte imbalance. The main mechanism causing this phenomenon is the release of potassium from excessive cells in vitro during clotting of the sample. Pseudohyperkalemia has no harmful consequences and an aggressive therapeutic approach is unnecessary.

In summary, for patients with portal cavernoma, if no common causes such as cirrhosis and neoplasm are found, investigations into an uncommon cause of MPD is indicated using bone marrow biopsy and coagulation profile. It is important to realize that the features of ET in peripheral blood cell counts could be masked by hypersplenism.

Peer reviewer: David Cronin II, MD, PhD, FACS, Associate Professor, Department of Surgery, Yale University School of Medicine, 330 Cedar Street, FMB 116, PO Box 208062, New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8062, United States

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Jensen MK, de Nully Brown P, Nielsen OJ, Hasselbalch HC. Incidence, clinical features and outcome of essential thrombocythaemia in a well defined geographical area. Eur J Haematol. 2000;65:132-139. |

| 2. | Ogren M, Bergqvist D, Björck M, Acosta S, Eriksson H, Sternby NH. Portal vein thrombosis: prevalence, patient characteristics and lifetime risk: a population study based on 23,796 consecutive autopsies. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2115-2119. |

| 3. | Denninger MH, Chaït Y, Casadevall N, Hillaire S, Guillin MC, Bezeaud A, Erlinger S, Briere J, Valla D. Cause of portal or hepatic venous thrombosis in adults: the role of multiple concurrent factors. Hepatology. 2000;31:587-591. |

| 4. | Valla DC, Condat B. Portal vein thrombosis in adults: pathophysiology, pathogenesis and management. J Hepatol. 2000;32:865-871. |

| 5. | Gangat N, Wolanskyj AP, Tefferi A. Abdominal vein thrombosis in essential thrombocythemia: prevalence, clinical correlates, and prognostic implications. Eur J Haematol. 2006;77:327-333. |

| 6. | Landolfi R, Di Gennaro L, Falanga A. Thrombosis in myeloproliferative disorders: pathogenetic facts and speculation. Leukemia. 2008;22:2020-2028. |

| 7. | Harrison CN. Essential thrombocythaemia: challenges and evidence-based management. Br J Haematol. 2005;130:153-165. |

| 8. | Harmanci O, Bayraktar Y. Portal hypertension due to portal venous thrombosis: etiology, clinical outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2535-2540. |

| 9. | Wolff M, Hirner A. Current state of portosystemic shunt surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2003;388:141-149. |

| 10. | Sevastos N, Theodossiades G, Efstathiou S, Papatheodoridis GV, Manesis E, Archimandritis AJ. Pseudohyperkalemia in serum: the phenomenon and its clinical magnitude. J Lab Clin Med. 2006;147:139-144. |