Published online Oct 28, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5097

Revised: September 27, 2009

Accepted: October 4, 2009

Published online: October 28, 2009

AIM: To investigate the efficacy and safety of rabeprazole under continuous non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) administration for NSAID-induced ulcer in Japan.

METHODS: Subjects comprised patients undergoing NSAID treatment in whom upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed an ulcerous lesion (open ulcer) with diameter ≥ 3 mm, who required continuous NSAID treatment. Endoscopies were performed at the start of treatment, during the treatment period, and at the conclusion (or discontinuation) of treatment. Findings were evaluated as size (maximum diameter) and stage based on the Sakita-Miwa classification. An ulcer was regarded as cured when the “white coating” was seen to have disappeared under endoscopy. As criteria for evaluating safety, all medically untoward symptoms and signs (adverse events, laboratory abnormalities, accidental symptoms, etc.) occurring after the start of rabeprazole treatment were handled as adverse events.

RESULTS: Endoscopic cure rate in 38 patients in the efficacy analysis (endoscopic evaluation) was 71.1% (27/38). Among those 38 patients, 35 had gastric ulcer with a cure rate of 71.4% (25/35), and 3 had duodenal ulcer with a cure rate of 66.7% (2/3). Three adverse drug reactions were reported from 64 patients in the safety analysis (interstitial pneumonia, low white blood cell count and pruritus); thus, the incidence rate for adverse drug reactions was 4.7% (3/64).

CONCLUSION: The treatment efficacy of rabeprazole for NSAID-induced ulcer under continuous NSAID administration was confirmed.

- Citation: Mizokami Y. Efficacy and safety of rabeprazole in non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced ulcer in Japan. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(40): 5097-5102

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i40/5097.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.5097

| Item | Subjects | ||

| n | % | ||

| Age at baseline (yr) | 20-39 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 40-64 | 16 | 42.1 | |

| ≥ 65 | 22 | 57.9 | |

| Sex | Male | 14 | 36.8 |

| Female | 24 | 63.2 | |

| Diagnosis | Gastric ulcer | 33 | 86.8 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 3 | 7.9 | |

| Gastric/duodenal ulcer | 2 | 5.3 | |

| Ulcer history | Initial occurrence | 15 | 39.5 |

| Reoccurrence | 13 | 34.2 | |

| Unknown | 10 | 26.3 | |

| Prior history | No | 28 | 73.7 |

| Yes | 10 | 26.3 | |

| History of allergies | No | 31 | 81.6 |

| Yes | 5 | 13.2 | |

| Unknown | 2 | 5.3 | |

| Type of NSAID (duplicates included) | Diclofenac sodium | 14 | 36.8 |

| Loxoprofen sodium | 14 | 36.8 | |

| Other | 15 | 39.5 | |

| Anti-ulcer treatment before rabeprazole treatment (within 1 mo) | No | 12 | 31.6 |

| Yes | 26 | 68.4 | |

| Concomitant medication (not including NSAIDs) | No | 5 | 13.2 |

| Yes | 33 | 86.8 | |

| Endoscopic findings before start of treatment (ulcer size) | 3 ≤ size < 10 mm | 21 | 55.3 |

| 10 ≤ size < 20 mm | 13 | 34.2 | |

| ≥ 20 mm | 4 | 10.5 | |

| Rabeprazole treatment duration | ≤ 56 d | 20 | 52.6 |

| > 56 d | 18 | 47.4 | |

| Rabeprazole dosage | 10 mg | 24 | 63.2 |

| 20 mg | 12 | 31.6 | |

| 10 mg→20 mg | 1 | 2.6 | |

| 20 mg→10 mg | 1 | 2.6 | |

| Item | Subjects | ||

| n | % | ||

| Age at baseline (yr) | 20-39 | 1 | 1.6 |

| 40-64 | 34 | 53.1 | |

| ≥ 65 | 29 | 45.3 | |

| Sex | Male | 27 | 42.2 |

| Female | 37 | 57.8 | |

| Diagnosis | Gastric ulcer | 57 | 89.1 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 4 | 6.3 | |

| Gastric/duodenal ulcer | 2 | 3.1 | |

| Anastomotic ulcer | 1 | 1.6 | |

| Ulcer history | Initial occurrence | 29 | 45.3 |

| Reoccurrence | 20 | 31.3 | |

| Unknown | 15 | 23.4 | |

| Prior history | No | 47 | 73.4 |

| Yes | 17 | 26.6 | |

| History of allergies | No | 55 | 85.9 |

| Yes | 6 | 9.4 | |

| Unknown | 3 | 4.7 | |

| Type of NSAID (duplicates included) | Diclofenac sodium | 34 | 53.1 |

| Loxoprofen sodium | 20 | 31.3 | |

| Other | 27 | 42.2 | |

| Anti-ulcer treatment before rabeprazole treatment (within 1 mo) | No | 19 | 29.7 |

| Yes | 45 | 70.3 | |

| Concomitant medication (not including NSAIDs) | No | 7 | 10.9 |

| Yes | 57 | 89.1 | |

| Endoscopic findings before start of treatment (ulcer size) | 3 ≤ size < 10 mm | 31 | 48.4 |

| 10 ≤ size < 20 mm | 25 | 39.1 | |

| ≥ 20 mm | 5 | 7.8 | |

| Unknown | 3 | 4.7 | |

| Rabeprazole treatment duration | ≤ 56 d | 27 | 42.2 |

| (gastric ulcer, gastric/duodenal ulcer, duodenal ulcer, anastomotic ulcer) | > 56 d | 37 | 57.8 |

| Rabeprazole dosage | 10 mg | 39 | 60.9 |

| 20 mg | 19 | 29.7 | |

| 10 mg→20 mg | 1 | 1.6 | |

| 20 mg→10 mg | 5 | 7.8 | |

| Site of ulcer | n | % | Ulcer form | n | % | No. of ulcers | n | % |

| Ulcer condition | ||||||||

| Corpus | 19 | 29.7 | Round | 27 | 42.2 | Single | 42 | 65.6 |

| Angle | 7 | 10.9 | Elliptical | 23 | 35.9 | Multiple | 21 | 32.8 |

| Antrum | 31 | 48.4 | Irregular | 11 | 17.2 | |||

| Bulb | 4 | 6.3 | Other | 2 | 3.1 | |||

| Efferent loop | 1 | 1.6 |

In clinical practice, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are widely prescribed for arthralgia and rheumatoid arthritis (RA)[1,2]. NSAIDs exert potent anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects but are clinically problematic in that gastric mucosal injury can be induced as an adverse reaction[3,4]. For example, up to 25% of patients using NSAIDs develop peptic ulcer[5,6]. A United States study reported that the number of people taking NSAIDs has reached 13 million per year, with approximately 100 000 requiring hospital treatment for upper gastrointestinal injury and 17 000 reported deaths annually[7]. The medical cost exceeds $4 billion per year in the USA[8].

In Japan, the Japan Rheumatism Foundation has reported the results of an epidemiological survey of the incidence of NSAID-induced gastric mucosal lesions in arthritis patients[9]. According to that report, of the 1008 patients with arthritis who took NSAIDs for ≥ 3 mo, upper gastrointestinal tract lesions were observed in 62.2%, including 15.5% with gastric ulcer and 1.9% with duodenal ulcer. This suggests that NSAID-induced gastric ulcers occur at a higher rate than the incidence of gastric ulcer found by physical examination (2.2%-4.1%). Moreover, more than 40% of patients were asymptomatic despite the presence of a lesion. In Japan, which faces an increasingly aging society, chronic diseases requiring long-term treatment with NSAIDs (e.g. RA, low back pain and arthralgia) are expected to increase. Devising methods for coping with the expected associated increases in gastric mucosal lesions will thus become increasingly important.

Preparations like proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and misoprostol are known for curing NSAID-induced gastrointestinal mucosal damage[10-13]. However, misoprostol often induces some adverse reactions like diarrhea[14].

Given this background, the “Evidence-Based Guidelines for Gastric Ulcer” were issued in 2003 (2nd edition in 2007) proposing policies for the treatment and prevention of NSAID-induced ulcers[15]. The guidelines recommend the following therapies: (1) if possible, discontinuation of NSAIDs and initiation of conventional ulcer treatment[16]; and (2) if NSAID treatment cannot be discontinued, initiation of treatment with a PPI or prostaglandin preparation. However, the evidence (clinical results) put forth in the guidelines was based entirely on foreign reports, with no evidence of use from Japanese studies[15].

Rabeprazole, a newer PPI, provides reliable control of gastric acid secretion, with more potent antisecretory activity than that of other PPIs such as omeprazole and lansoprazole, a more rapid rise in intragastric pH, and less effect of CYP2C19 on its metabolism[17-20].

Based on our belief in the importance of investigating the efficacy and safety of the PPI rabeprazole on NSAID-induced ulcers in Japanese individuals, we conducted this survey of 38 medical departments (primarily departments of gastroenterology and internal medicine) at 38 facilities nationwide. This survey was conducted between 1 August 2004 and 31 January 2006, in accordance with good post-marketing surveillance practice.

Subjects included in this survey were patients undergoing NSAID treatment in whom upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed an ulcerous lesion (open ulcer) with diameter ≥ 3 mm, who required continuous NSAID treatment. Patients taking low-dose aspirin to prevent clot/thrombus formation were excluded as subjects. Patients meeting any of the following criteria were also excluded: (1) history of hypersensitivity to rabeprazole components; (2) exposed blood vessels in the ulcer base; or (3) judged by an investigator as unsuitable for participation in this survey.

A central registration system was adopted. The registration form was mailed within 1 wk of the registration date. Rabeprazole were to be administered in accordance with the following dose: once daily oral administration of 10 mg of rabeprazole sodium, which can be increased to once daily oral administration of 20 mg, depending on the symptoms (Standard dosage for adults): Standard treatment duration is 8 wk in the case of gastric or anastomotic ulcer, and 6 wk in the case of duodenal ulcer. The Japanese standard dosages of the three most used NSAIDs in this study are as follows; diclofenac sodium, 25-100 mg/d; loxoprofen, 60-180 mg/d; lornoxicam, 12-18 mg/d.

Endoscopic findings: Endoscopies were performed at the start of treatment, during the treatment period, and at the conclusion (or discontinuation) of treatment. Findings were evaluated as size (maximum diameter) and stage based on the Sakita-Miwa classification. When multiple ulcers existed in a single subject, only the largest one was recorded. An ulcer was regarded as cured when the “white coating” was seen to have disappeared under endoscopy.

Adverse events: As criteria for evaluating safety, all medically untoward symptoms and signs (adverse events, laboratory abnormalities, accidental symptoms, etc.) occurring after the start of rabeprazole treatment were handled as adverse events.

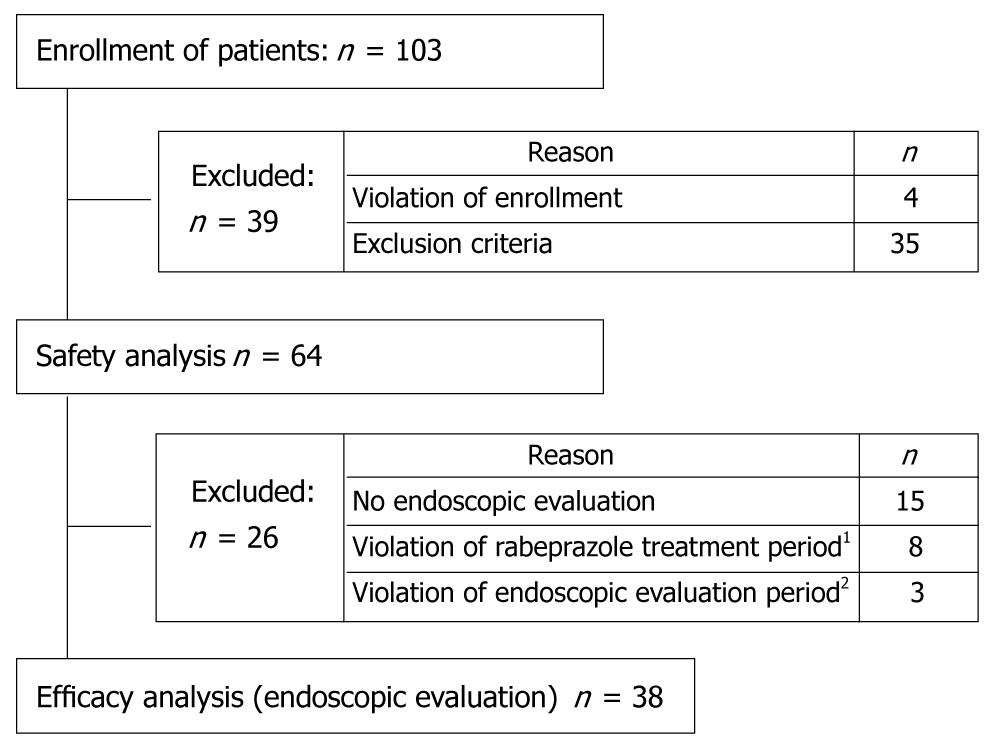

One hundred three patients were enrolled in the present study. Due to violation of enrollment and patients meeting exclusion criteria like no concomitant use of NSAIDs, 38 patients were put in the efficacy analysis and 64 patients in the safety analysis (Figure 1).

Demographic and baseline characteristics: Demographic and baseline characteristics of the 38 patients in the efficacy analysis (endoscopic evaluation) are shown in Table 1. Well-used NSAIDs by patients were diclofenac sodium in 36.8% (14/38), loxoprofen 36.8% in (14/38) and lornoxicam in 13.2% (5/38). The main reasons for use of NSAIDs observed were RA in 39.5% (15/38) and low back pain in 36.8% (14/38).

Among 25 subjects undergoing examination for Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) infection, 64.0% (16/25) were positive, and 36.0% (9/25) were negative.

Endoscopic cure rate: Endoscopic cure rate for the 38 patients in the efficacy analysis (endoscopic evaluation) was 71.1% (27/38) (Table 2). According to diagnosis, the cure rate was 71.4% (25/35) for gastric ulcer and 66.7% (2/3) for duodenal ulcer. In addition, the cure rate was lower in the gastric antrum (55.6%; 10/18) than in the gastric corpus (91.7%; 11/12).

Demographic and baseline characteristics: Demographic and baseline characteristics of 64 patients in the safety analysis are shown in Table 3. Well-used NSAIDs by patients were diclofenac sodium in 53.1% (34/64), loxoprofen in 31.3% (20/64) and lornoxicam in 10.9% (7/64). The main reasons for using NSAIDs were RA in 40.6% (26/64), low back pain in 28.1% (18/64) and osteoarthritis in 15.6% (10/64). Among 42 subjects undergoing examination for H pylori infection, 59.5% (25/42) were positive, and 40.5% (17/42) were negative.

Incidence of adverse drug reactions: Among the 64 patients in the safety analysis, 3 adverse drug reactions were observed in 3 patients. The incidence rate for adverse drug reactions was thus 4.7% (3/64). Adverse reactions comprised 1 case of “interstitial pneumonia” (serious; outcome: recovering) (1.6%); 1 case of “low white blood cell count” (non-serious; outcome: recovered) (1.6%); and 1 case of “pruritus” (non-serious; outcome: recovered) (1.6%).

Endoscopic cure rate was 71.1% (27/38). By disease, the endoscopic cure rate in gastric ulcer patients after 8 wk of treatment was 71.4% (25/35) and the endoscopic cure rate in duodenal ulcer patients after 6 wk of treatment was 66.7% (2/3). In other clinical studies of rabeprazole, reported cure rates have been 93.5% (72/77 patients)[21] and 96.4% (27/28) for gastric ulcer, and 100% (23/23) for duodenal ulcer[22]. Endoscopic cure rate in this survey, at 71.1%, did not reach the general cure rates obtained for chronic gastric and duodenal ulcers. These results strongly suggest that continuous administration of NSAIDs may act to delay ulcer healing.

Conversely, in studies similar to this study relating to the healing of gastric and duodenal ulcers in the presence of NSAID treatment, according to the results of Shiokawa et al[23] in the first such study in Japan, cure rates for gastric and duodenal ulcer were 70% (35/50) and 83.3% (5/6), respectively, when a prostaglandin was used at 800 μg/d. With regard to the healing effect of PPI use, only results from foreign studies are available[24-27]. Hawkey et al[26] conducted a comparative examination of the results of studies on the effects of 20 mg and 40 mg of omeprazole, and 800 μg of misoprostol. After 8 wk of administration, the gastric ulcer cure rate was 87.2% (102/117) with 20 mg of omeprazole and 79.5% (105/132) with 40 mg. The cure rate in the group administered 20 mg of omeprazole was significantly higher than the 72.8% (91/125 patients) in the control group administered 800 μg of misoprostol. In a study of lansoprazole, Agrawal et al[27] compared the results of 15 mg and 30 mg of lansoprazole versus 300 mg of ranitidine hydrochloride. Gastric ulcer cure rates after 8 wk of treatment were 68.6% (81/118) with 15 mg lansoprazole and 72.6% (85/117) with 30 mg. Cure rates in both lansoprazole groups were significantly higher than the 53.0% (61/115 patients) obtained using ranitidine hydrochloride. The present survey found no significant difference between rabeprazole doses with respect to cure rates for NSAID-induced ulcer, with a cure rate of 70.8% (17/24) using a dose of 10 mg and 75.0% (9/12) at 20 mg. The cure rates observed here did not differ significantly from those obtained using the other PPIs described above.

Conversely, how H pylori infection affects healing of NSAID-induced ulcers remains controversial and is an important topic that should be considered in future studies, and a recently published guideline addressed this point[28]. This survey investigated the dependency of cure rate on H pylori infection, but no significant difference was observed. The cure rate in H pylori-positive patients was 81.3% (13/16), compared to 77.8% (7/9) in H pylori-negative patients.

Symptoms and signs, and the conditions of occurrence of these presentations, are commonly considered to differ between NSAID-induced ulcer patients and patients with ordinary ulcers. Saigenji et al reported that the pretreatment incidence of epigastralgia was 100% (72/72 patients) in patients with gastric ulcer[21]. However, the pretreatment incidence rate for epigastralgia was 70.2% (33/41) in the present survey, which was comparatively lower than the incidence observed with ordinary gastric ulcer. In general, incidences for symptoms and signs are lower with NSAID-induced ulcers[29], and the present results support this.

Data on the site, shape and number of NSAID-induced ulcers were also tabulated in this survey. For the 90 patients with NSAID-induced ulcer (not including the 9 patients in the dataset of patients analyzed who did not display NSAID-induced ulcer), the original ulcer site was most frequent at the gastric antrum (43.3%) and the most common shapes were round (35.6%) and elliptical (37.8%), although irregularly shaped ulcers were also observed (23.3%). In terms of the number of ulcers, multiple ulcers were present in 33.3% (30/90) of cases. The clinical characteristics of NSAID-induced ulcers that were confirmed in the 64 patients in the safety analysis were also tabulated. The gastric antrum was the site of the ulcer in 48.4% (31/64) of patients; the shape was round in 42.2% (27/64) and elliptical in 35.9% (23/64) while 32.8% (21/64) of cases displayed multiple ulcers (Table 4).

NSAID-induced ulcer in gastric antrum, the most common in the present study, seemed to be harder to cure compared to NSAID-induced ulcers in the gastric corpus or gastric angle, as reported by Mizokami et al[30].

Measures for responding to NSAID-induced lesions found in normal medical examinations will become increasingly important as society continues to age. This survey, conducted in accordance with the guidelines, proposes one direction for treatment.

A non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) is widely prescribed for patients with rheumatoid arthritis, low back pain, etc. However, NSAID damages gastrointestinal mucosa and induces peptic ulcers. Use of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) is recommended to cure those peptic ulcers.

This multicenter study all over Japan revealed the safety profile and efficacy of rabeprazole, a type of PPI, for NSAID-induced ulcer.

This is one of the studies to investigate the safety profile and efficacy of rabeprazole for NSAID-induced ulcer.

Safety and efficacy of rabeprazole was comparable to other types of PPIs, which means more diversity of treatment options for patients suffering from NSAID-induced ulcer, and this is important since the number of patients using NSAIDs is expected to increase in the aging society in Japan.

The manuscript by Mizokami provides the results of studies on the efficacy and safety of rabeprazole for ulcerous lesions in patients undergoing NSAID treatment. This is a reasonable study and the data are well presented.

This survey was conducted in 38 medical facilities nationwide under the direction of the late Professor Shinichi Ota. We wish to express sincere gratitude to all the participating physicians as follows: Hiroyuki Hisai, Date Red Cross Hospital; Toshimi Chiba, Iwate Medical Unversity Hospital; Harufumi Oizumi, Oizumi Gastrointestinal and Medical Clinic; Yuji Mizokami, Tokyo Medical University Kasumigaura Hospital; Hideharu Miyabayashi, National Hospital Organization Matsumoto National Hospital; Naoshi Nakamura, Marunouchi Hospital; Akihiko Suzuki, Japanese Red Cross Azumino Hospital; Yoshihiro Matsukawa, Nihon University Itabashi Hospital; Kazuo Kashiwazaki, Kyosai Tachikawa Hospital; Norihiko Tonozuka, Akishima Hospital; Toru Segawa, National Hospital Organization, Murayama Medical Center; Toshifumi Kita, Fujimura Hospital; Koji Yakabi, Saitama Medical Center, Saitama Medical University; Shinichi Ota, Saitama Medical University Hospital; Yoshihiro Matuskawa, Kamifukuoka Kyodo Clinic; Akira Tokunaga, Nippon Medical School, Musashikosugi Hospital; Masakazu Tomiyama, Yokohama Minami Kyosai Hospital; Naoto Mitsugi, Yokohama City University Medical Center; Tetsuya Mine, Tokai University Hospital; Yoshifumi Yokoyama, Higashi Municipal Hospital, City of Nagoya; Hiroaki Iwase, National Hospital Organization Nagoya Medical Center; Masahiro Mitake, Suzuki-Mitake Clinic; Shin Yamamoto, Kansai Medical University Takii Hospital; Junichi Yamao, Nara Medical University Hospital; Nobuo Aoyama, Kobe University Hospital; Norimasa Yoshida, University Hospital, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine; Atsushi Sugahara, Kawasaki Hospital, Kawasaki Medical School; Hironao Komatsu, JA Hiroshima Koseiren Hiroshima General Hospital; Tomohiko Shimatani, Shinji Tanaka, Hiroshima University Hospital; Seizo Yamana, Higashi-Hiroshima Memorial Hospital; Hitoshi Hasegawa, Ehime University Hospital; Takahiro Horie, Tokushima Prefectural Miyoshi Hospital; Hiroaki Kubo, Fukuoka Prefectural Kaho Hospital; Tetsuya Ishida, Oita Red Cross Hospital; Aoi Yoshiiwa, Oita University Hospital; Masahiro Yoshinaga, National Hospital Organization Beppu Medical Center; Shinji Nasu, Yamaga Hospital; Shinsuke Nagai, Kagoshima Red Cross Hospital.

Peer reviewer: Bronislaw L Slomiany, PhD, Professor, Research Center, C-875, UMDNJ-NJ Dental School, 110 Bergen Street, PO Box 1709, Newark, NJ 07103-2400, United States

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Hungin AP, Kean WF. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: overused or underused in osteoarthritis? Am J Med. 2001;110:8S-11S. |

| 2. | Lichtenstein DR, Syngal S, Wolfe MM. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and the gastrointestinal tract. The double-edged sword. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:5-18. |

| 3. | Soll AH, Weinstein WM, Kurata J, McCarthy D. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and peptic ulcer disease. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:307-319. |

| 4. | Goldstein JL. Challenges in managing NSAID-associated gastrointestinal tract injury. Digestion. 2004;69 Suppl 1:25-33. |

| 5. | Larkai EN, Smith JL, Lidsky MD, Graham DY. Gastroduodenal mucosa and dyspeptic symptoms in arthritic patients during chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:1153-1158. |

| 6. | Laine L. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug gastropathy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1996;6:489-504. |

| 7. | Singh G. Recent considerations in nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug gastropathy. Am J Med. 1998;105:31S-38S. |

| 8. | Bidaut-Russell M, Gabriel SE. Adverse gastrointestinal effects of NSAIDs: consequences and costs. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;15:739-753. |

| 9. | Shiokawa Y, Nobunaga M, Saito T, Asaki S, Ogawa N. Epidemiology study on upper gastrointestinal lesions induced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Ryumachi. 1991;31:96-111. |

| 10. | Regula J, Butruk E, Dekkers CP, de Boer SY, Raps D, Simon L, Terjung A, Thomas KB, Luhmann R, Fischer R. Prevention of NSAID-associated gastrointestinal lesions: a comparison study pantoprazole versus omeprazole. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1747-1755. |

| 11. | Lanza FL, Fakouhi D, Rubin A, Davis RE, Rack MF, Nissen C, Geis S. A double-blind placebo-controlled comparison of the efficacy and safety of 50, 100, and 200 micrograms of misoprostol QID in the prevention of ibuprofen-induced gastric and duodenal mucosal lesions and symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:633-636. |

| 12. | Targownik LE, Metge CJ, Leung S, Chateau DG. The relative efficacies of gastroprotective strategies in chronic users of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:937-944. |

| 13. | Lanza FL. A double-blind study of prophylactic effect of misoprostol on lesions of gastric and duodenal mucosa induced by oral administration of tolmetin in healthy subjects. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31:131S-136S. |

| 14. | Silverstein FE, Graham DY, Senior JR, Davies HW, Struthers BJ, Bittman RM, Geis GS. Misoprostol reduces serious gastrointestinal complications in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:241-249. |

| 15. | Ota S. NSAID ulcer. Japanese guideline for the management of gastric ulcer. 2nd ed. Tokyo: Jiho Inc 2007; 101-106. |

| 16. | Lancaster-Smith MJ, Jaderberg ME, Jackson DA. Ranitidine in the treatment of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug associated gastric and duodenal ulcers. Gut. 1991;32:252-255. |

| 17. | Saitoh T, Fukushima Y, Otsuka H, Hirakawa J, Mori H, Asano T, Ishikawa T, Katsube T, Ogawa K, Ohkawa S. Effects of rabeprazole, lansoprazole and omeprazole on intragastric pH in CYP2C19 extensive metabolizers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1811-1817. |

| 18. | Adachi K, Katsube T, Kawamura A, Takashima T, Yuki M, Amano K, Ishihara S, Fukuda R, Watanabe M, Kinoshita Y. CYP2C19 genotype status and intragastric pH during dosing with lansoprazole or rabeprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1259-1266. |

| 19. | Ando T, Ishikawa T, Kokura S, Naito Y, Yoshida N, Yoshikawa T. Endoscopic analysis of gastric ulcer after one week’s treatment with omeprazole and rabeprazole in relation to CYP2C19 genotype. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:933-937. |

| 20. | Yamano HO, Matsushita HO, Yanagiwara S. Plasma concentration of rabeprazole after 8-week administration in gastroesophageal reflux disease patients and intragastric pH elevation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:534-540. |

| 21. | Saigenji K, Yokota K, Kure T, Konno J, Mochizuki F, Mitaji T, Eda K, Komatsu M, Iizuka Y, Mizokami Y. Clinical evaluation of Pariet 10mg tablets in patients with gastric ulcer diseases. Jpn Pharmacol Ther. 2002;30:675-693. |

| 22. | Nakazawa S, Yoshino J, Yamachika H, Ito M, Nakano H, Miyaji I, Tsukamoto Y, Goto H, Hase S, Hayashi S. Early phase clinical study of E3810 on gastric and duodenal ulcer. Mod Physician. 1994;14:1-22. |

| 23. | Shiokawa Y, Nobunaga M, Saito T, Sakita T, Miwa T, Nakamura K, Gunji A, Aoki K. Evaluation of misoprostol’s clinical utility for gastric/duodenal ulcers seen under long-term use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID)--II. Evaluation of therapeutic effects on ulcers under continuous use of NSAID. Ryumachi. 1991;31:572-582. |

| 24. | Yeomans ND, Tulassay Z, Juhasz L, Racz I, Howard JM, van Rensburg CJ, Swannell AJ, Hawkey CJ. A comparison of omeprazole with ranitidine for ulcers associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Acid Suppression Trial: Ranitidine versus Omeprazole for NSAID-associated Ulcer Treatment (ASTRONAUT) Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:719-726. |

| 25. | Campbell DR, Haber MM, Sheldon E, Collis C, Lukasik N, Huang B, Goldstein JL. Effect of H pylori status on gastric ulcer healing in patients continuing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory therapy and receiving treatment with lansoprazole or ranitidine. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2208-2214. |

| 26. | Hawkey CJ, Karrasch JA, Szczepanski L, Walker DG, Barkun A, Swannell AJ, Yeomans ND. Omeprazole compared with misoprostol for ulcers associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Omeprazole versus Misoprostol for NSAID-induced Ulcer Management (OMNIUM) Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:727-734. |

| 27. | Agrawal NM, Campbell DR, Safdi MA, Lukasik NL, Huang B, Haber MM. Superiority of lansoprazole vs ranitidine in healing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-associated gastric ulcers: results of a double-blind, randomized, multicenter study. NSAID-Associated Gastric Ulcer Study Group. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1455-1461. |

| 28. | Lanza FL, Chan FK, Quigley EM. Guidelines for prevention of NSAID-related ulcer complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:728-738. |

| 29. | Armstrong CP, Blower AL. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and life threatening complications of peptic ulceration. Gut. 1987;28:527-532. |

| 30. | Mizokami Y, Shiraishi T, Otsubo T, Kariya Y, Nakamura H, Narushima K, Matsuoka T. Effect of Antiulcer Drugs for Treatment of Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drug-Induced Ulcers. Trends in Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2001;215-218. |