INTRODUCTION

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is characterized by the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies and multiple systemic abnormalities including arterial or venous thrombosis, fetal loss, thrombocytopenia, leg ulcers, livedo reticularis, chorea, and migraine[12345]. Venous thrombosis commonly involves deep venous system of the leg, but the renal vein, pulmonary vein, inferior vena cava, hepatic vein, and portal vein may also be involved[267]. The most common site of arterial thrombosis is the cerebral circulation, but occlusion of coronary, renal, or retinal arteries has also been reported[67]. Only rarely has mesenteric arterial thrombosis been noted[16]. We report an unusual case where APS was first manifested by infarction and cecal perforation following cesarean section.

CASE REPORT

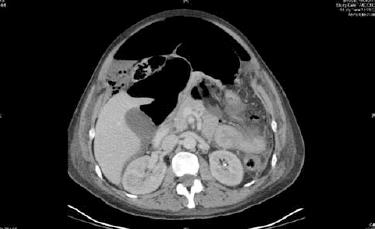

A 37-year-old lady was admitted for elective induction of labor, but proceeded to have an emergency cesarean section due to prolonged second stage of labor. During the postpartum period she developed abdominal distention and exhibited signs of peritonitis. Laboratory tests showed a leukocyte count of 21 × 109 with 19 × 109 neutrophils, hemoglobin of 11.9 g/dL and INR of 1.15. Renal and liver biochemistries were normal. Computerized tomography (CT) revealed a large amount of free gas and free fluid in the abdomen indicative of bowel perforation (Figure 1).

Figure 1 CT revealed free gas and fluid in the abdomen.

After initial resuscitation, she underwent emergency laparotomy which revealed generalized fecal peritonitis and multiple perforations of the cecum. Macroscopically the entire right colon looked inflamed. After peritoneal lavage a right hemicolectomy was performed. A double barrelled stoma (ileo-colostomy) was fashioned due to fecal soiling of the peritoneal cavity and unknown etiology of the perforation. Post operative recovery was complicated by intra-abdominal serous collections, necessitating percutaneous drainage, and pleural effusion for which she needed a chest drain insertion.

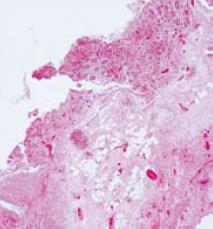

Histopathology of the resected bowel revealed transmural infarction with the presence of occasional fibrin thrombi in adjacent blood vessels without evidence of vasculitis (Figure 2). Background bowel and the resection margins showed peritonitis, but the wall was viable and did not show any significant abnormalities.

Figure 2 Histopathology showed bowel wall necrosis.

Clotting profile confirmed the presence of lupus anti-coagulant, but it was negative for anticardiolipin antibodies. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) revealed occlusion of the inferior mesenteric artery and stenosis of the hepatic artery. Ultrasound scan of the hepatobiliary system was normal. A diagnosis of APS was established and she was subsequently commenced on life-long warfarin (target INR 3-4).

The stoma was closed 4 mo later after a normal contrast enema. The patient made an uneventful recovery and remains well on follow-up.

DISCUSSION

APS is characterized by a state of hypercoagulability potentially posing a risk of thrombosis to all segments of the vascular bed and may result in pregnancy related morbidity. It is associated with the presence of a specific group of autoantibodies called antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) which are circulating immunoglobulins that cross-react with cell membrane phospholipids. The two main types of aPL are the anticardiolipin antibodies (aCL) and the lupus anticoagulant (LA). These antibodies are found in 2% of the general population and in 30%-40% of systemic lupus erythematosus patients[78]. Although patients with syphilis, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or other connective tissue disorders may have these antibodies, they may not manifest clinical features. About 30% of patients with the LA and 30%-50% with high or medium positive IgM aCL antibodies have clinical features of APS. The exact prevalence remains unknown[9]. The aCL test is positive in about 80% of patients with APS, the LA positive in approximately 20%, and both are present in 60% of the cases[10]. The Sapporo criteria require the positivity on two occasions, at least 6 wk apart of aCL at medium-high titres or LA[11]. However, this was recently revised to 12 wk by international consensus[12].

Anticardiolipin antibodies are strongly associated with thromboembolic phenomenon, thrombocytopenia, and prolonged prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times[8]. The suggested mechanisms for reaction of antibodies with epitopes are anticardiolipin binding to acidic phospholipids on platelet membranes resulting in platelet activation[1314], anticardiolipin blocking prothrombinase activation, anticardiolipin binding to membrane phospholipids to cause endothelial cell injury, and anticardiolipin alteration of the local endothelial levels of prostacyclin, prekallikrein, antithrombin III, or protein C[15161718]. However, lupus anticoagulants are a stronger risk factor for thrombosis than anticardiolipin antibodies in APS[19]. This was the case in our patient who was anticardiolipin negative, but lupus anticoagulant positive.

A wide range of abdominal manifestations of APS have been reported, with hepatic involvement being the most common, followed by thrombotic events involving different branches of the intestinal vasculature[20]. Sporadic splenic infarction and acute pancreatitis have also been reported. A wide range of hepatic diseases are associated with APS including both thrombotic (Budd-Chiari syndrome and hepatic infarction) and non-thrombotic conditions (cirrhosis, autoimmune hepatitis and portal hypertension). Intestinal infarction, due to thrombosis of mesenteric vessels, has been relatively less frequently reported in patients with APS[21].

Cases of mesenteric venous thromboses presenting with intestinal ischemia in patients with APS have been reported in the literature[22]. The presentation may be acute, often preceded by intestinal angina, or rarely results in intestinal bleeding and ulceration[20]. The occurrence of celiac artery and/or superior mesenteric artery stenosis has also been documented[23].

Computerized tomography (CT) is considered to be first-line investigation in APS patients presenting with abdominal symptoms. CT features of mesenteric ischemia have been reported to show thickening of both small and large bowel walls with prominence of the supplying mesenteric vessels[24]. Mesenteric MRA (magnetic resonance angiogram) in cases of suspected intestinal ischemia may confirm the diagnosis if the patients’ condition allows. In our case, the patient underwent an emergency laparotomy and spontaneous perforation of the cecum was found. The underlying cause, however, was not clear at the time of surgery and the diagnosis of APS was made during post-operative hospital stay.

Venous or arterial intestinal thromboses and infarctions may be prominent features of APS. The presentation may be non-specific and a high index of suspicion is needed for any signs of abdominal involvement in these patients. Pregnancy poses increased risks of complications (e.g. hypertension/pre-eclampsia, prematurity or thrombosis) and requires a more aggressive approach to the obstetric care. This should include full anticoagulation in the puerperium and frequent ultrasound monitoring with uterine and umbilical artery Doppler blood flow analyses to detect complications such as pre-eclampsia and placental insufficiency.

It is recommended that all women with APS should maintain antithrombotic treatment throughout their entire pregnancy and during the postpartum period. The treatment of choice is combined low-dose aspirin and full antithrombotic doses of low molecular weight heparin. In high risk groups, such as history of previous thrombotic events, warfarin may be used during pregnancy, but only after organogenesis (6th-12th wk) because of high risks of fetal malformations. Despite the significant risks associated with pregnancy in patients with APS, with the correct management the likelihood of a live birth is around 75%-80%[25].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report in the English literature of spontaneous colonic perforation due to APS following cesarean section. Our patient was previously fit and healthy and received the standard prophylaxis for thromboembolism with low molecular weight heparin. The underlying APS in combination with pregnancy and surgery, both of which are risk factors for thromboembolism, caused mesenteric thrombosis and cecal infarction.