INTRODUCTION

Figure 1 Iron up-regulates HMOX1 mRNA levels in Huh-7, 9-13 and CNS3 cells.

A: HMOX1 mRNA levels in Huh-7, 9-13 and CNS3 cells; B: HMOX1 mRNA levels in Huh-7 cells treated with 100 μmol/L FeNTA or 1 mmol/L H2O2 for 6 h; C: HMOX1 mRNA levels in 9-13 cells treated with 100 μmol/L FeNTA or 1 mmol/L H2O2 for 6 h; D: HMOX1 mRNA levels in CNS3 cells treated with 100 μmol/L FeNTA or 1 mmol/L H2O2 for 6 h. Values for cells without any treatment were set equal to 1. HMOX1 mRNA data are presented as means ± SE from triplicate samples, all normalized to GAPDH in the same samples. aP < 0.05 vs control. Huh-7, 9-13 or CNS3 cells were cultured as described in Materials and Methods, and treated with 100 μmol/L FeNTA or 1 mmol/L H2O2 for 6 h. Cells were harvested and total RNA was extracted. Levels of mRNA for HMOX1 and GAPDH were measured by quantitative RT-PCR.

Figure 2 Effects of FeNTA on Nrf2 protein levels in Huh-7, 9-13, and CNS3 cells.

A: Nrf2 protein levels in Huh-7 cells; B: Nrf2 protein levels in 9-13 cells; C: Nrf2 protein levels in CNS3 cells. aP < 0.05 vs control. Huh-7, 9-13 or CNS3 cells were treated with different concentrations of FeNTA (0, 20, 50, 100 μmol/L) or 100 μmol/L NaNTA for 6 h, after which cells were harvested and total protein was isolated, as described in Materials and Methods. Proteins were separated on 4%-15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a PVDF membrane, and probed with anti-human Nrf2 and GAPDH specific antibodies. The relative amounts of Nrf2 proteins were normalized to GAPDH.

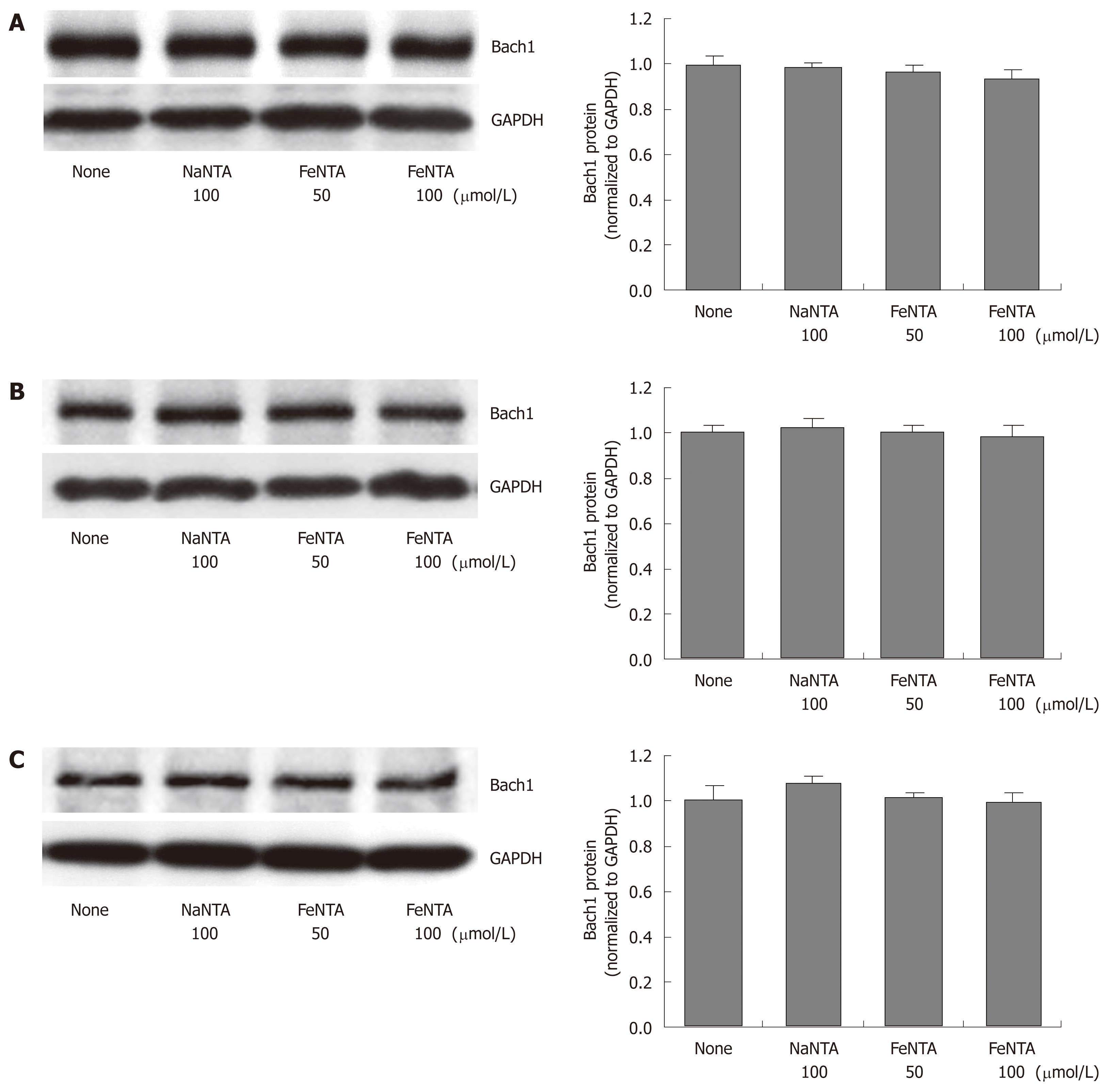

Figure 3 Effects of FeNTA on Bach1 protein levels in Huh-7, 9-13, and CNS3 cells.

A: Bach1 protein levels in Huh-7 cells; B: Bach1 protein levels in 9-13 cells; C: Bach1 protein levels in CNS3 cells. Huh-7, 9-13 or CNS3 cells were treated with different concentrations of FeNTA (0, 50, 100 μmol/L) or 100 μmol/L NaNTA for 16 h, after which cells were harvested and total protein was isolated, as described in Material and Methods. Proteins were separated on 4%-15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a PVDF membrane, and probed with anti-human Bach1 and GAPDH specific antibodies. The relative amounts of Bach1 were normalized to GAPDH.

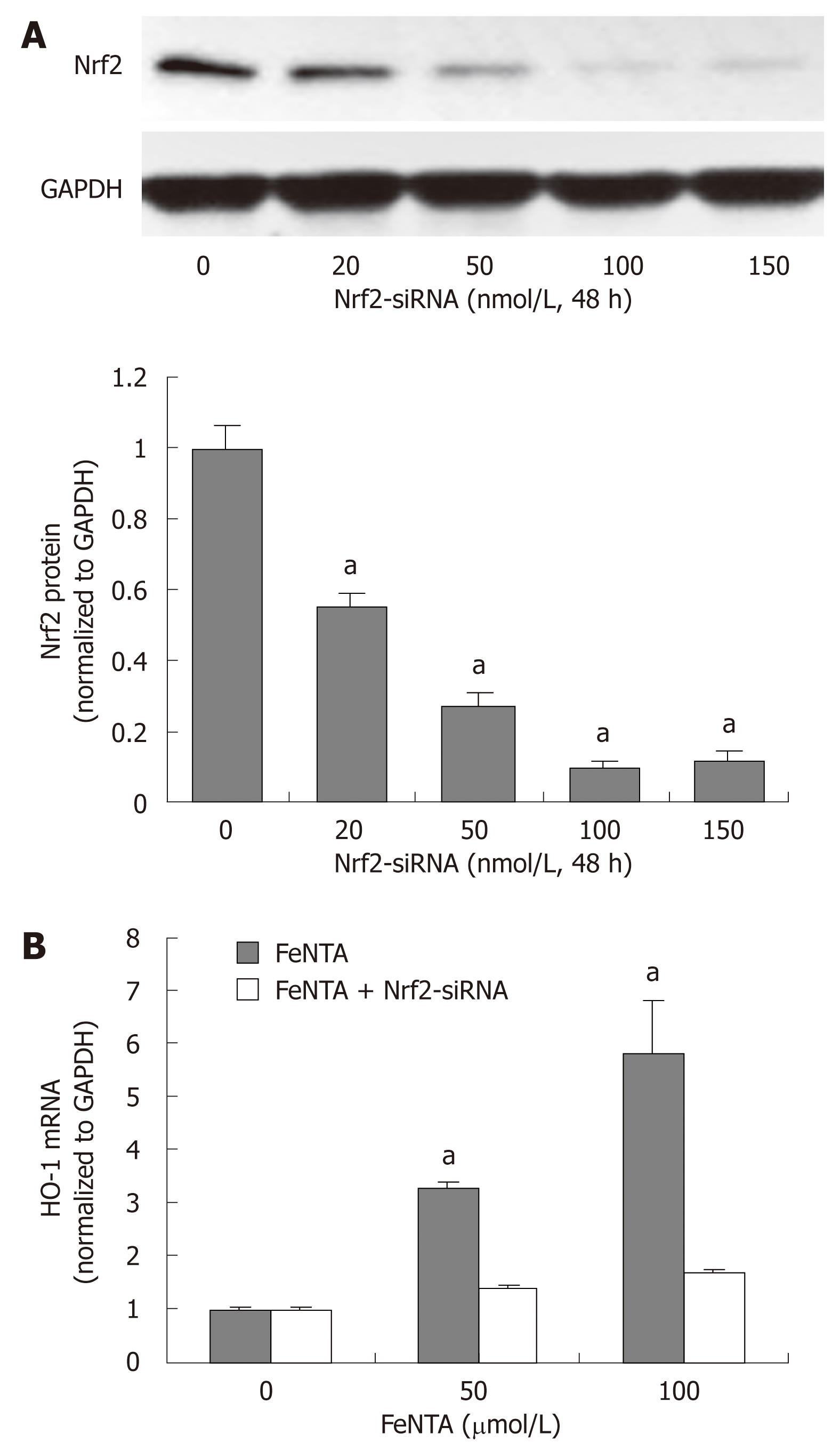

Figure 4 Silencing the Nrf2 gene abrogates up-regulation of the HMOX1 gene by iron.

A: Dose-response effect of Nrf2-specific siRNA on Nrf2 protein levels; B: Effect of Nrf2-specific siRNA on FeNTA up-regulated levels of HMOX1 mRNA. aP < 0.05 vs control. 9-13 cells were transfected with selected concentrations of Nrf2-siRNA (0, 20, 50, 100, 150 nmol/L). After 48 h of transfection, cells were treated with different concentrations of FeNTA (0, 50, 100 μmol/L) for 6 h, after which cells were harvested and total RNA was isolated. The HMOX1 mRNA levels were measured by quantitative RT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods.

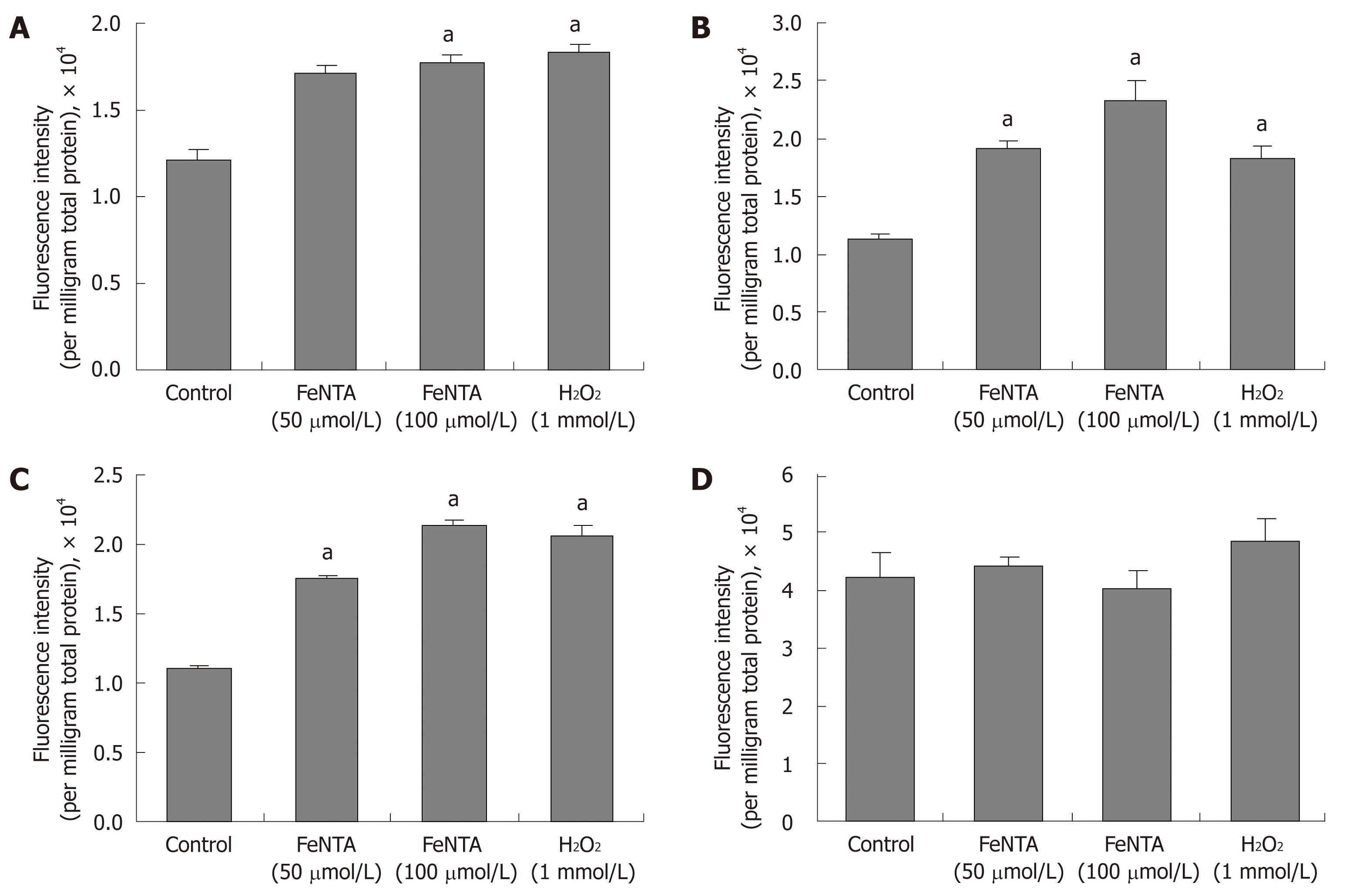

Figure 5 Effects of FeNTA on intracellular ROS in Huh-7, 9-13, and CNS3 cells.

A: Fluorescence intensity with the H2DCF-DA probe in Huh-7 cells; B: Fluorescence intensity with the H2DCF-DA probe in 9-13 cells; C: Fluorescence intensity with the H2DCF-DA probe in CNS3 cells; D: Fluorescence intensity with the (control) DCF-DA in CNS3 cells. Cells were preincubated with 100 μmol/L H2DCF-DA or DCF-DA for 30 min, and then exposed to selected concentrations of FeNTA (0, 50, 100 μmol/L) for 1 h. Intracellular ROS production was measured as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent fluorescence intensity measured and expressed as relative fluorescence units per milligram total protein (mean ± SE, n = 3 experiments). aP < 0.05 vs control.

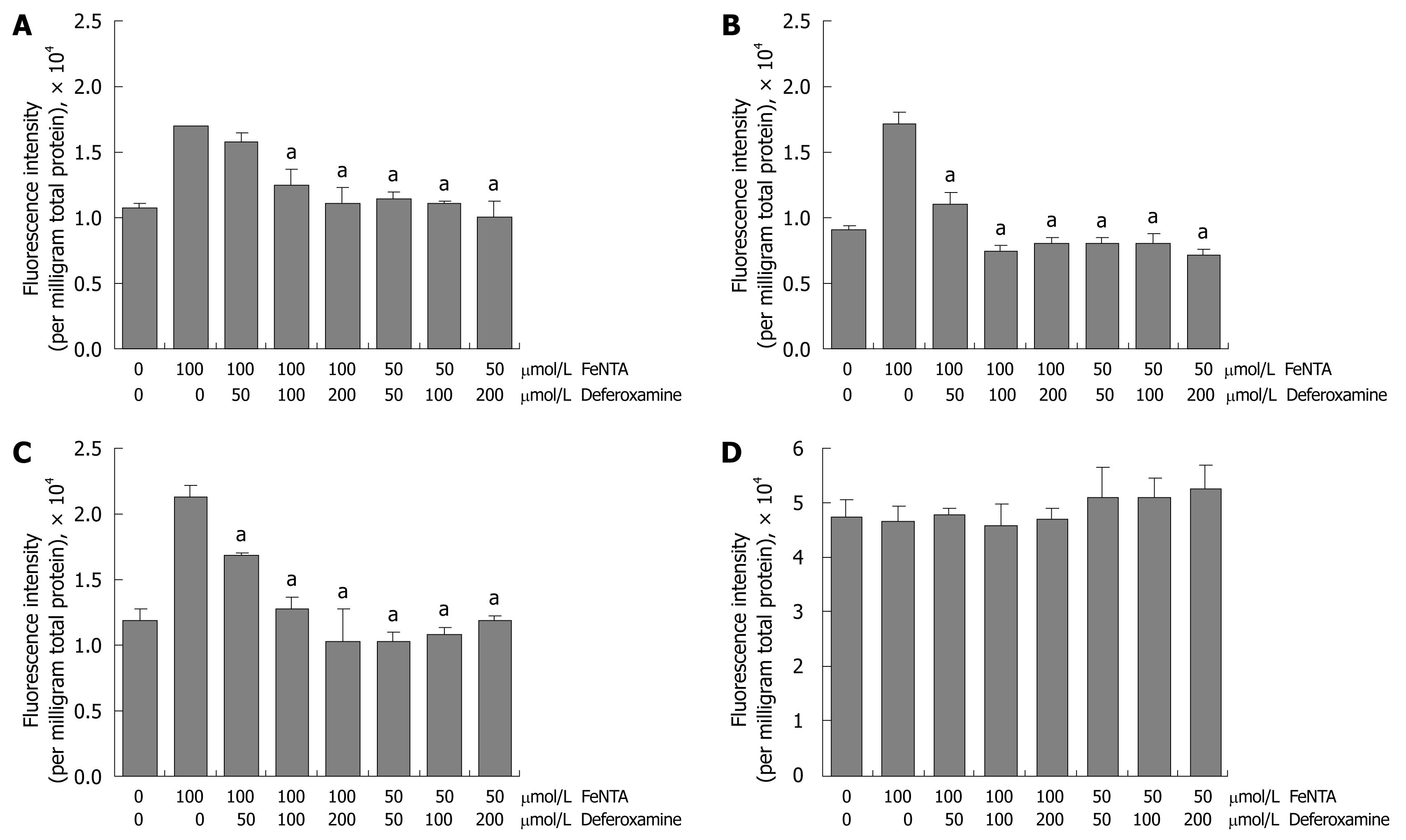

Figure 6 Effects of deferoxamine on intracellular ROS induced by FeNTA in Huh-7, 9-13, and CNS3 cells.

A: Fluorescence intensity with the H2DCF-DA probe in Huh-7 cells; B: Fluorescence intensity with the H2DCF-DA probe in 9-13 cells; C: Fluorescence intensity with the H2DCF-DA probe in CNS3 cells; D: Fluorescence intensity with the (control) DCF-DA in CNS3 cells. Cells were loaded with 100 μmol/L H2DCF-DA for 30 min, treated with different concentrations of deferoxamine (50, 100, 200 μmol/L) for 30 min, and then exposed to different concentrations of FeNTA (50, 100 μmol/L) for 1 h. Intracellular ROS production was measured as described in Materials and Methods.

Figure 7 Effects of FeNTA on HCV core and NS5A mRNA and protein levels.

A: Core mRNA levels in Con1 cells treated with FeNTA and with or without deferoxamine; B: Core protein levels in Con1 cells treated with FeNTA and with or without deferoxamine; C: NS5A mRNA levels in Con1 cells treated with FeNTA and with or without deferoxamine; D: NS5A protein levels in Con1 cells treated with FeNTA and with or without deferoxamine. Data are presented as mean ± SE from triplicate samples, all normalized to GAPDH in the same samples. aP < 0.05 vs control. The Con1 full length HCV replicon cells were treated with indicated concentrations of FeNTA and with or without deferoxamine. After 24 h, cells were harvested and total RNA and proteins were extracted. Levels of mRNA were measured by quantitative RT-PCR, and protein levels were determined by Western blots as described in Materials and Methods. Values for cells without any treatment were set equal to 1.

Iron overload is known to be toxic to many organs, particularly to the liver. The liver is the major site of storage of excess iron. The most common form of iron overload is that related to classic hereditary hemochromatosis, in which, due to mutations in the HFE gene, there is excessive uptake of iron into enterocytes[1-3]. In hemochromatosis, decreased hepatic production and secretion of hepcidin leads to increased ferroportin expression at the plasma membranes, especially of enterocytes and macrophages. Ferroportin is the only known physiologic iron exporter from cells and its uncontrolled over expression leads to excess uptake of iron from the enterocytes into the portal blood and to increased release of iron from macrophages and other cells of the reticulo-endothelial system, including the Kupffer cells of the liver[4-6]. The excess iron in the portal blood and/or released by Kupffer cells within the liver is taken up by hepatocytes where it is stored, chiefly in the form of holo-ferritin. Iron in ferritin is relatively non-reactive and non-toxic. However, release of tissue ferritin from damaged or dying cells leads to activation of hepatic stellate cells and a cascade of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrogenic events. This may eventuate in the development of hepatic fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as all of the usual complications of advanced chronic liver disease[7-9].

In recent years, it has become increasingly clear that only modest amounts of iron in the liver may play a role as a co-morbid factor in the development and progression of non-hemochromatotic liver diseases[10-15]. The link between iron and non-hemochromatotic liver diseases is particularly strong for steatohepatitis, both non-alcoholic and alcoholic[10,14,15] and viral hepatitis B and C[16-18].

Porphyria cutanea tarda, the most common form of porphyria, is known to be triggered or exacerbated by iron and is often associated with HFE gene mutations, chronic hepatitis C, and alcohol use[19-21]. The treatment of choice for porphyria cutanea tarda involves removal of iron, which leads to remission of the biochemical and clinical features of the disease. Blumberg and colleagues were among the first to stress the importance of iron status in influencing outcomes and progression of acute hepatitis B infection[22,23]. In the case of hepatitis C infection, a number of investigators from throughout the world have noted high prevalences (35%-50%) of elevations of serum ferritin and high, albeit somewhat lower, frequencies of elevations of serum transferrin saturation in patients with chronic hepatitis C[10,24-26]. Despite this, the occurrence of heavy iron overload in chronic hepatitis C is infrequent and is chiefly related to advanced liver disease. Increases in serum measures of iron and stainable iron in the liver have been directly correlated with more severe chronic hepatitis C and with lower likelihoods of response to currently available antiviral therapy, especially type 1 interferons[24,27,28]. In addition, it has been shown repeatedly that reduction of body iron by therapeutic phlebotomy improves the responsiveness of chronic hepatitis C infection to interferon therapy[29].

Heme oxygenase-1 (HMOX1) has emerged as a key cytoprotective gene and enzyme in numerous experimental and clinical contexts (For reviews, see[30-33]). The HMOX1 gene is under complex regulation and can be up-regulated markedly by heme, the physiologic substrate for the HMOX1 protein, by iron and other transition metallic ions, and by oxidative and heat stress and other stressful perturbations. Regulation of HMOX1 gene expression is related in part to alterations in levels of several transcription factors, including Bach1, and nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2). Normally, Bach1 in nuclei represses HMOX1 gene expression, whereas Nrf2, in concert with small Maf proteins, up-regulates its expression[34-36].

The study of hepatitis C viral (HCV) infection has been difficult because of the lack of a readily available, inexpensive animal model of acute or chronic hepatitis C infection. The recent development of human hepatoma cell lines, which stably express HCV proteins, and support the replication of HCV RNA or the formation of complete infectious virions of HCV[37,38], has facilitated studies on pathogenesis and the role of potential co-morbid factors, such as iron. We used such lines to investigate the effects of iron on oxidative stress, HMOX1 and HCV expression. Here we report that excess iron results in further increased oxidative stress and up-regulation of HMOX1 via Nrf2, and down-regulation of HCV protein expression in human hepatoma cells in culture (Huh-7) expressing HCV RNA and proteins. These effects are reversed by deferoxamine (DFO), the selective and potent iron chelator.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and materials

Mouse anti-HCV nonstructural 5A (NS5A) protein was purchased from Virogen (Plantation, FL). Goat anti-human Bach1, goat anti-human GAPDH polyclonal antibodies, goat anti-mouse IgG, and donkey anti-goat IgG were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc (Santa Cruz, CA). ECL-Plus was purchased from Amersham Biosciences Corp (Piscataway, NJ). Dimethyl sulfoxide was purchased from FisherBiotech (Fair Lawn, NJ). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), zeocin, geneticin, trypsin and TRIzol were from Invitrogen Inc. (Carlsbad, CA). FeCl3, Na3NTA, H2O2, 2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCF-DA) and its oxidation-insensitive analog 2’,7’-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Allentown, PA). DFO mesylate was from Novartis (Cambridge, MA).

Cell cultures

The human hepatoma cell line, Huh-7, was purchased from the Japan Health Research Resources Bank (Osaka, Japan). 9-13 and CNS3 cell lines derived from Huh-7 cells, which stably express HCV proteins were gifts from Dr. R Bartenschlager (University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany). Human hepatoma Huh-7 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 10% (v/v) FBS. 9-13 and CNS3 replicon cells were cultured with additional antibiotics (1 mg/mL geneticin or 10 μg/mL zeocin), respectively. 9-13 replicon cells stably express HCV nonstructural proteins (NS3-5B), and CNS3 cells stably express subgenomic proteins from core to nonstructural protein 3 (core-NS3). The Con1 subgenomic genotype 1b HCV replicon cell line was from Apath LLC (St, Louis, MO). The Con1 cell line is a Huh-7.5 cell population containing the full-length HCV genotype 1b replicon. The Con1 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS and 0.1 mmol/L nonessential amino acids, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and selection antibiotic 750 μg/mL geneticin. Cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 95% room air and 5% CO2 at 37°C.

siRNA transfection

A smart pool of siRNAs targeting four positions of the human Nrf2 mRNA, was purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). Transfections of Nrf2-siRNA were performed with Lipofectamine 2000 from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) as described previously[35]. Cells were transfected for 48 h with 20-100 nmol/L Nrf2-siRNA, or an irrelevant control, and subsequently were exposed for 4 h to indicated concentrations of ferric nitrilotriacetate (FeNTA). Cells were harvested and total RNA and proteins were extracted for measurements of mRNA or protein levels by quantitative RT-PCR or Western blots.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA from treated cells was extracted and cDNA was synthesized and real time quantitative RT-PCR was performed using a MyiQ™ Single Color Real-Time PCR Detection System (BIO-RAD) and iQ™ SYBR Green Supermix Real-Time PCR kit (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA) as described previously[39,40]. Sequence-specific primers used for HMOX1, HCV core, NS5A and GAPDH were synthesized. We included samples without template and without reverse transcriptase as negative controls, which were expected to produce negligible signals (Ct values > 35). Standard curves of HMOX1, HCV core, NS5A and GAPDH were constructed with results of parallel PCR reactions performed on serial dilutions of a standard DNA (from one of the controls). Fold-change values were calculated by comparative Ct analysis after normalizing for the quantity of GAPDH in the same samples.

Western blotting

Protein preparations and Western blots were performed as described previously[39,40]. In brief, total proteins (30-50 μg) were separated on 4%-15% gradient SDS-PAGE gels (Bio-Rad). After electrophoretic transfer onto immunoblot PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad), membranes were blocked for 1 h in PBS containing 5% nonfat dry milk and 0.1% Tween-20, and then incubated overnight with primary antibody at 4°C. The dilutions of the primary antibodies were as follows: 1:500 for anti-NS5A, 1:1000 for anti-Bach1, 1:2000 for anti-HCV core and anti-GAPDH antibodies. The membranes were then incubated for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (dilution 1:10 000). Finally, the bound antibodies were visualized with the ECL-Plus chemiluminescence system according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). A Kodak 1DV3.6 computer-based imaging system (Eastman-Kodak, Rochester, NY) was used to measure the relative optical density of each specific band obtained after western blotting. Data are expressed as percentages of the controls (corresponding to the value obtained with the vehicle-treated cells), which were assigned values of one.

Cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) production assay

Levels of cellular oxidative stress were measured using DCF assay. Briefly, cells were seeded into 24-well plates. The following day, the media were removed, and the cells were washed with PBS (PBS supplemented with 1 mmol/L CaCl2 and 0.5 mmol/L MgCl2), and then incubated with 100 μmol/L 2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein (H2DCF-DA) or 2’,7’-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA) in DMEM without phenol red for 30 min at 37°C in the dark. The cells were washed twice with PBS, and then treated with selected concentrations of FeNTA for 1 h. Intracellular ROS levels were measured as an increase in fluorescence of the oxidized product of DCF-DA on a Synergy HT Multi-Detection Microplate Reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT) at the excitation and emission wavelengths of 488 and 525 nm, respectively. The oxidation-insensitive analog of H2DCF-DA served as a control to correct for possible changes in cellular uptake, ester cleavage, and efflux. It showed no changes in fluorescence in these studies.

Statistical analysis

Experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results. Except for Western blots, all experiments included at least triplicate samples for each treatment group. Representative results from single experiments are presented. Statistical analyses were performed with JMP 6.0.3 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Initial interpretation of data showed that they were normally distributed. Therefore, appropriate parametric statistical procedures were used: Student’s t-test for comparisons of two means and analysis-of-variance (F statistics) for comparisons of more than two, with pair-wise comparisons by the Kruskal-Wallis test. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Iron up-regulates HMOX1 mRNA levels in Huh-7 and cell lines expressing HCV proteins

As shown in Figure 1, HMOX1 gene expression was significantly increased in CNS3 cells, which express HCV core to NS3, even without exposure to iron or hydrogen peroxide, compared to 9-13 cell lines, which express NS3 to NS5B, or parental Huh-7 cells. Iron, in the form of FeNTA and hydrogen peroxide (another known oxidative stressor), further up-regulated the HMOX1 gene expression in CNS3 cells. Increase of HMOX1 gene expression by iron in Huh-7 (6.7 fold) and 9-13 cells (5.2 fold) was greater than in CNS3 cells (1.9 fold).

Effects of Iron on Nrf2 and Bach1 protein levels in Huh-7 and cell lines expressing HCV proteins

Previous studies from our and other laboratories have demonstrated that Bach1 and Nrf2 act as transcriptional factors that regulate HMOX1 gene expression in mammalian cells[34-36], and that Huh-7 cells expressing HCV proteins show significant up-regulation of the HMOX1 gene, and reciprocal down-regulation of the Bach1 gene[41]. To determine whether iron affected the Nrf2 or Bach1 gene expression, parental Huh-7 and cell lines (9-13 and CNS3) expressing HCV proteins were treated with FeNTA, and Nrf2 and Bach1 protein levels were measured by Western blots, as described in Materials and Methods. Cells exposed to 50 and 100 μmol/L FeNTA showed significant accumulation of Nrf2 protein (Figure 2A-C), whereas 50 or 100 μmol/L NaNTA did not affect Nrf2 protein levels (data not shown). In contrast, there were no detectable changes of Bach1 protein levels in either Huh-7 cells or cell lines expressing HCV proteins, suggesting that Bach1 is not involved in up-regulation of the HMOX1 gene expression by iron (Figure 3A-C).

Nrf2-siRNA abrogates up-regulation of the HMOX1 gene expression by iron in 9-13 cells

To further establish the role of Nrf2 in up-regulation of the HMOX1 gene expression by iron, we silenced Nrf2 gene expression by Nrf2-siRNA as we did previously in Huh-7 cells[35]. In comparison with control, 20 nmol/L Nrf2-siRNA significantly reduced Nrf2 protein expression, and 100 nmol/L Nrf2-siRNA repressed Nrf2 protein expression by 92% (Figure 4A). We also successfully silenced the Nrf2 gene expression in CNS3 cells (data not shown). HMOX1 mRNA levels were significantly induced by iron in cells without Nrf2-siRNA transfection, and this effect was blocked in cells transfected with 100 nmol/L Nrf2-siRNA, indicating that Nrf-2 siRNA plays a key role in up-regulation of the HMOX1 gene expression by iron (Figure 4B).

Increased ROS, induced by iron, in the form of ferric nitrilotriacetate, in the cell lines expressing HCV proteins

Oxidative stress is one of the key stressors inducing the HMOX1 gene expression[30,31], occurring due to iron-catalyzed formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)[42]. We observed that the cells exposed to 50 μmol/L FeNTA exhibited significant increases in the fluorescence intensity of H2DCF-DA (by 1.4 fold in Huh-7, 1.7 fold in 9-13 and 1.6 fold in CNS3 cells), which are similar to the increases produced by hydrogen peroxide (1 mmol/L). 100 μmol/L FeNTA further increased fluorescence intensity by 2.1 fold in 9-13 and 1.9 folds in CNS3 cells (Figure 5A-C), whereas 50 or 100 μmol/L NaNTA did not affect fluorescence intensity (data not shown). The results of the same experiment done with the oxidation-insensitive analogue of the probe (DCF-DA) in CNS3 (Figure 5D), Huh-7 and 9-13 cells (data not shown) indicated no significant difference between control cells and cells treated with FeNTA or H2O2. Therefore, the increased fluorescence intensity seen with the oxidation sensitive probe H2DCF-DA (Figure 5A-C) can be directly ascribed to changes in the oxidation of the probe in the cells. We also changed the order of adding the H2DCF-DA and FeNTA or H2O2 and observed the same pattern of results (data not shown).

The iron chelator DFO blocks increased ROS induced by iron in the cell lines expressing HCV proteins

DFO and deferasirox (Exjade) are widely used iron chelators to remove excess iron from the body. They act by binding iron at 1:1 (deferoxamine:iron) and 2:1 (deferasirox:iron) ratios and enhancing its elimination. By removing excess iron, these agents reduce the damage done by iron to various organs and tissues such as the liver. In this study, DFO was used to examine whether the effects of FeNTA were blocked by DFO chelation. In comparison with 100 μmol/L FeNTA alone, 50 μmol/L DFO (deferoxamine:iron 1:2) significantly decreased DCF fluorescence intensity in 9-13 and CNS3 cells (Figure 6A-C). Indeed, ROS induced by iron were completely blocked by DFO in all three cell lines treated with 50 μmol/L FeNTA and increasing concentrations of DFO (50, 100 and 200 μmol/L) (Figure 6A-C). To confirm we were truly measuring changes in H2DCF-DA oxidation and not changes in its uptake, ester cleavage, or efflux, we repeated experiments shown in Figure 6A-C with the oxidation-insensitive analogue of the probe (DCF-DA). No significant differences between control and treated cells were found in CNS3 (Figure 6D), Huh-7 or 9-13 cells (data not shown).

Iron decreases HCV protein expression in cell lines expressing HCV proteins

To evaluate the effect of iron in the form of FeNTA on HCV RNA and protein expression, Con1 full length HCV replicon cells were exposed to FeNTA and with or without DFO. Treatment with FeNTA resulted in a 80%-90% reduction in HCV core mRNA and protein levels (Figure 7A and B), and decreased expression of HCV NS5A mRNA by about 90% and protein by about 50% (Figure 7C and D), whereas no significant effects were produced by NaNTA, establishing that the effects are due to iron and not to the nitrilotriacetate anion (data not shown). These down-regulatory effects were abrogated by DFO (200 μm).

DISCUSSION

The major findings of this work are as follows: (1) Iron, in the form of FeNTA, up-regulates HMOX1 gene expression in human Huh-7, and cell lines (9-13 and CNS3) stably expressing HCV proteins (Figure 1); (2) Iron significantly increases Nrf2 protein levels in human hepatoma cells, and silencing the Nrf2 gene with Nrf2-specific siRNA abrogates the up-regulation of HMOX1 by iron (Figures 2 and 4); (3) Iron does not significantly change Bach1 protein levels in human hepatoma cells (Figure 3); (4) Iron increases ROS (Figures 5 and 6) but decreases HCV gene expression (Figure 7) in human hepatoma cells; and (5) These effects are blocked by the selective iron chelator DFO (Figures 5-7). However, none of the effects is produced by Na3NTA, establishing that they are due to iron and not to the NTA anion. These results show clearly that iron is capable of acting directly on hepatoma cells and on HCV gene expression in hepatoma cells, without the need for mediation of effects by other tissues, organs, or cell types. Thus, it appears that iron exerts manifold effects on HCV-infected hepatocytes. On the one hand, it increases ROS and oxidative stress, acting in concert with HCV proteins, especially the core protein. On the other hand, it induces HMOX1 by increasing expression and activity of Nrf2 (Figures 1, 2 and 4), and it decreases levels of CNS3 or NS5A mRNA and protein expression (Figure 7). These latter effects are likely mediated by the recently described iron-dependent inactivation of the HCV RNA polymerase NS5B[43].

HMOX1 is a heat shock protein (also known as HSP 32), which can be induced to high levels, not only by heat shock, but also by a large number of physiological or pathological stressors[30-33]. Nrf2 is a basic leucine zipper transcriptional activator[44,45]. It protects cells against oxidative stress through antioxidant response element (ARE)-directed induction of several phase 2 detoxifying and antioxidant enzymes, including HMOX1[35,46]. Nrf2-/- mice displayed a dramatically increased mortality associated with liver failure when fed doses of ethanol that were tolerated by wild type mice, establishing a central role of Nrf2 in the natural defense against ethanol-induced liver injury[47]. Cobalt protoporphyrin (CoPP)-mediated induction of HMOX1 involves increased Nrf2 protein stability in human hepatoma Huh-7 cells[35]. In this study, silencing Nrf2 by Nrf2-siRNA markedly abrogated FeNTA-mediated up-regulation of HMOX1 mRNA levels. Therefore Nrf-2 plays a central role in up-regulation of HMOX1 gene expression by FeNTA (Figure 4B).

Bach1, a member of the basic leucine zipper family of proteins, has been recently shown to be a transcriptional repressor of HMOX1, and to play a critical role in heme-, CoPP-, SnMP- and ZnMP-dependent up-regulation of the HMOX1 gene[35,36,48-53]. Upon exposure to heme, heme binds to Bach1 and forms antagonizing heterodimers with proteins in the Maf-related oncogene family. These heterodimers bind to MAREs, also known as AREs, and suppress expression of genes that respond to Maf-containing heterodimers and other positive transcriptional factors. Surprisingly, ZnMP does not bind to Bach1, but it still produces profound post-transcriptional down-regulation of Bach1 protein levels by increasing proteasomal degradation and transcriptional up-regulation of HMOX1[53]. In contrast, iron does not affect levels of Bach1 mRNA (data not shown) or protein (Figure 3), suggesting that Bach1 is not involved in up-regulation of the HMOX1 gene by iron.

Expression of HMOX1 was recently reported to be decreased in human livers from patients with chronic hepatitis C[54,55] including some with only mild fibrosis. The reasons for this are not known currently. It is known that levels of expression of the HMOX1 gene depend in part upon genetic factors (lengths of GT repeats in the promoter[56-59] and a functional polymorphism (A/T) at position -413 of the promoter[60,61]. Higher expression and/or induction of HMOX1 are probably beneficial to mitigate liver cell injury in HCV infection, as well as in other liver diseases. This may be a therapeutic goal, achieved by treatment with heme or CoPP or with silymarin[62] or other herbal products or compounds that combine anti-oxidant, iron-chelating and HMOX1-inducing effects.

Recently, we showed that HCV expression in CNS3 cells increases the levels of HMOX1 mRNA and protein[41]. This induction is likely in response to oxidative stress. More recently, we showed that micro RNA-122, which is expressed at a high level in hepatocytes, causes down-regulation of Bach1, which, as already described, tonically down-regulates the HMOX1 gene[40]. In addition, we and others have shown that expression of micro RNA-122 is required for HCV replication in human hepatoma cells[40,63,64]. Whether iron affects levels of micro RNA-122 has not yet been assessed, to our knowledge.

Others recently reported that iron binds to NS5B, the RNA dependent RNA polymerase of HCV, and inhibits its enzymatic activity[43]. The HCV replicon system used in that study showed changes in the gene expression of certain genes involved in iron metabolism, including down-regulation of ceruloplasmin and transferrin receptor 1 but up-regulation of ferroportin thus producing an iron-deficient phenotype[65]. The authors speculated that the HCV genes and proteins somehow produced these changes in order to diminish the effects of iron to inhibit NS5B RNA polymerase activity and to decrease HCV protein expression.

Regardless of these results in cell culture models, the preponderance of clinical evidence[10-15,24-29] supports the view that iron acts as a co-morbid or synergistic factor in chronic hepatitis C infection. Because both iron and HCV infection increase oxidative stress within hepatocytes, one attractive mechanistic explanation for the additive or synergistic affects of these two perturbations is that they act, at least in part, by increasing oxidative stress in the form of highly reactive oxygen species. These considerations provide additional rationale for the notion that reduction of iron and anti-oxidant therapy[62] may be of benefit in the management of difficult to cure chronic hepatitis C[10-15,24-29,66-68]. Iron reduction has usually been achieved with therapeutic phlebotomies. However, deferasirox (Exjade) recently has been approved in the USA and other countries as oral chelation therapy for iron overload states. Thus, studies of deferasirox for therapy of chronic hepatitis C are timely and important[69], especially because the therapy of chronic hepatitis C currently is fraught with side effects, difficulties of adherence and rates of response that are not better than about 50%[70-72].

In conclusion, iron can cause or exacerbate liver damage, including viral hepatitis. In the work reported in this paper we assessed effects of iron and iron chelators on liver cells, some of which also expressed genes and proteins of the HCV. Iron increased oxidative stress and led to up-regulation of the HMOX1 gene, a key cytoprotective gene. A mechanism for this action was to increase expression of the positive transcription factor Nrf-2. In contrast, iron did not affect expression of Bach1. Iron decreased expression of HCV genes and proteins. All the effects of iron were abrogated by DFO. The induction of HMOX1 helps to protect liver cells from the damaging effects of the HCV.