Published online Sep 14, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4327

Revised: August 12, 2009

Accepted: August 19, 2009

Published online: September 14, 2009

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract has been reported in both immunocompetent and, more frequently, in immunocompromised patients. We describe a case of a 19-year-old male who developed CMV infection of the terminal ileum while receiving immunosuppression for lupus nephritis. This was a distinctly unusual site of infection which clinically mimicked Crohn’s ileitis. We note that reports of terminal ileal CMV infection have been infrequent. Despite a complicated hospital course, ganciclovir therapy was effective in resolving his symptoms and normalizing his ileal mucosa. This report highlights the importance of accurate histological diagnosis and clinical follow-up of lupus patients with GI symptoms undergoing intense immunosuppression.

- Citation: Khan FN, Prasad V, Klein MD. Cytomegalovirus enteritis mimicking Crohn’s disease in a lupus nephritis patient: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(34): 4327-4330

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i34/4327.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.4327

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract has been reported in both immunocompetent and, more frequently, in immunocompromised patients[1,2]. Sometimes the presentation of this infection can mimic other illnesses, making accurate diagnosis difficult. As the therapy for this infection can be very toxic, and discontinuation of therapeutic immunosuppression can cause worsening of the underlying pathology, accurate diagnosis is essential. The case presented here illustrates the difficulty in making an accurate diagnosis, while highlighting the fascinating mimicry which CMV can display.

A 19-year-old white male presented with a 3-wk history of increasing malaise, weakness, fever, and arthralgia. He had no significant past medical history or family medical history and was on no medications. Outpatient workup revealed elevated acute serum Lyme and Ehrlichia titers for which he received oral doxycycline. Two weeks later, he presented with fever, arthralgia and a malar rash, along with mild diffuse abdominal pain and diarrhea. Physical examination demonstrated hypertension (blood pressure 150/90 mmHg), lower extremity edema, and mild diffuse abdominal tenderness. A complete blood count and comprehensive chemistry profile revealed pancytopenia (white blood cells 3000/mm3, hematocrit 25% and platelets 100 000/mm3), elevated transaminases (aspartate transaminase 250 IU/L and alanine transaminase 271 IU/L), albumin 2 g/dL, nephrotic range proteinuria (5 g/d) and a urinalysis with red blood cells and red cell casts, consistent with glomerular hematuria. His creatinine was 0.8 mg/dL with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 130 mL/min. Serologic examination was significant for depressed complement components C3 and C4, a high titer antinuclear antibody 1:320, a positive anti-double stranded DNA antibody, erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 65 with negativity for c-ANCA (antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody) and p-ANCA. A bone marrow biopsy was non diagnostic. Renal biopsy revealed features of World Health Organization class IV and class V lupus nephritis. He was treated with pulsed methylprednisolone 1 g daily for 3 d along with 1.2 g (0.7 g/m2) cyclophosphamide by intravenous infusion. He continued on prednisone 80 mg/d orally. His immediate course was complicated by a transient psychotic reaction which required rapid tapering of the steroids. Subsequently his blood counts, liver function and clinical symptoms improved, and he was discharged home with close outpatient follow-up.

Approximately one month after receiving cyclophosphamide, he developed fever, severe debilitating watery diarrhea with abdominal pain, and presented to the emergency room in acute renal failure (creatinine 2.0 mg/dL). The renal dysfunction resolved completely after the administration of intravenous saline, but the GI symptoms persisted. Urinalysis demonstrated persistent hematuria and proteinuria. Routine stool studies, including cultures, occult blood and Clostridium difficile toxin were negative. The diarrhea was intractable with a large stool osmolar gap, hypoalbuminemia of 1.4 g/dL, and depressed cyanocobalamin levels, consistent with malabsorption and protein-losing enteropathy. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) demonstrated edema of the small intestinal wall, particularly in the ileum. A small bowel barium study clearly demonstrated a “string sign” with long narrowed segments of distal jejunum and ileum consistent with Crohn’s jejuno-ileitis (Figure 1). At the time, the differential diagnosis also included lupus vasculitis of the GI tract, ileal tuberculosis, actinomycosis, lymphoma, amoebiasis, or viral infection. Stool acid-fast bacilli and amoebic serologies were negative. An initial colonoscopy showed an inflammatory stricture with friable, erythematous and edematous mucosa at the terminal ileum, 2 cm proximal to the ileocecal junction through which the scope could not be passed.

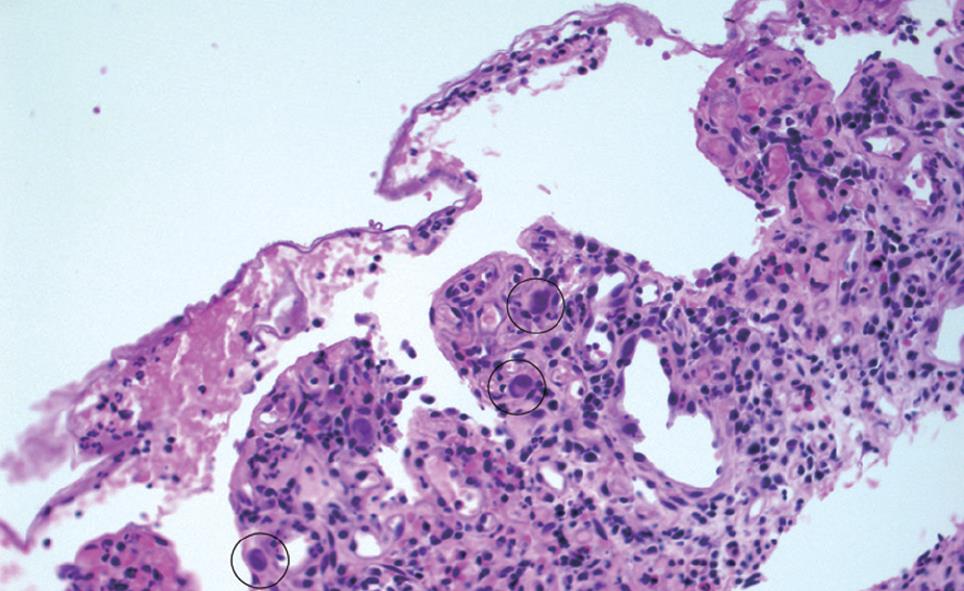

Multiple biopsies were obtained but were not diagnostic. A CT angiogram, performed to rule out lupus vasculitis demonstrated a normal mesenteric vasculature. A subsequent colonoscopy one week later demonstrated persistently inflamed and denuded mucosa with a persistent terminal ileal stricture. Terminal ileal biopsies clearly revealed intranuclear basophilic inclusions consistent with CMV infection which was confirmed by immunocytochemical staining (Figure 2). No evidence of granulomas or vasculitis was seen on histology. Based on this finding alone, further immunosuppression was deferred, and the patient was started on intravenous ganciclovir 5 mg/kg twice daily. His subsequent hospital course was complicated by continued diarrhea, protein-losing enteropathy, severe malnutrition requiring total parenteral nutrition, fungal sepsis, and subclavian deep venous thrombosis. Ganciclovir was continued for 4 wk. Ultimately he recovered fully. His abdominal symptoms resolved, and he was able to tolerate an oral diet before discharge.

A repeat colonoscopy 4 mo later found resolution of the stricture, with no inclusion bodies seen on repeat biopsy. After this confirmation, cyclophosphamide and glucocorticoid therapies for lupus nephritis were resumed, with oral ganciclovir prophylaxis. There were no further infectious sequelae. He has had no further complications on follow-up and was switched to mycophenolate mofetil maintenance therapy. Currently he has normal renal function, no proteinuria or hematuria and continued quiescent lupus serology.

CMV is a double-stranded DNA virus and a member of the herpesviridae family.

During primary infection, T-cells are vital in controlling the viral replication, but do not eliminate the virus completely. This leads to a latent infection. Acute CMV infection in immunocompetent hosts can manifest with transient nonspecific symptoms, or as a systemic disease with significant organ involvement[3]. It is estimated that 50%-80% of the adult population is seropositive for the virus[4]. In immunocompromised hosts, re-activation or re-infection can lead to overt disease e.g., pneumonitis, hepatitis, pancreatitis, colitis, encephalitis, retinitis, or pericarditis leading to substantial morbidity and mortality. Transplant recipients and HIV infected patients with CMV enteritis had a mortality rate as high as 44% in one study[5].

Immunosuppressive therapies for lupus have well documented infectious risks. Cyclophosphamide is a potent alkylating agent that impairs T-cell immunity at even low to moderate doses. In contrast to cancer chemotherapeutic doses, the doses given for lupus nephritis do not usually result in profound effects. However, leukopenia and opportunistic infections can sometimes supervene. Data on the incidence of CMV disease with the cyclophosphamide induction protocol for lupus are scarce. The Euro-Lupus Nephritis Trial documented 3 cases out of 45 lupus nephritis patients on intravenous cyclophosphamide[6].

The protean manifestations of lupus, together with the numerous possible complications of therapy, present unique problems for the treating physician. Lupus vasculitis has been reported to mimic Crohn’s ileitis[7]. The perplexing question in this case was whether the patient’s symptoms represented this rare manifestation of GI lupus vasculitis, versus the coexistence of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and Crohn’s disease, an infectious complication of immunosuppression, or a fourth, less likely, possibility that the patient’s CMV infection was the etiology of his abdominal pain at the time of his initial presentation with SLE, and thus predated his immunosuppression. The transient leukopenia and elevated transaminases on initial presentation, though not unusual for active systemic lupus, could have been the result of primary CMV infection in this spontaneously immunocompromised host.

The acute onset of CMV disease has been described in up to 46% of patients with connective tissue disease undergoing immunosuppressive therapy[8]. It has also been noted that patients with connective tissue diseases treated with immunosuppression are at high risk for reactivation of latent CMV disease[9]. Any part of the GI tract may be affected by CMV. Colitis is the most common manifestation of gastrointestinal CMV and can occur either alone or with other systemic involvement. CMV infection of the small bowel, though reported, is distinctly rare, especially in apparently immunocompetent hosts, and only involves 4.3% of CMV infections of the GI tract[3,10]. CMV enteritis presents most commonly with fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea, or hemorrhage. The virus directly infects the bowel causing mucosal erosions or ulcerations. In severe cases, tissue necrosis and bowel wall perforation can occur[1]. Histology of the affected mucosa shows a nonspecific inflammatory reaction and giant cells with ovoid nuclei containing basophilic “Cowdry” inclusion bodies. Mesenchymal cells are infected most frequently (97%) followed by endothelial cells (35%), smooth muscle cells (6%) and epithelial cells (3%). Mucosal ulcers are seen in more than half the cases[10,11]. CMV ileitis in lupus patients is rare, but has been reported to cause ileal perforation[12]. Though one case found CT evidence of bowel wall thickening[7], we found no cases described in association with the radiographic “string sign”. As mentioned, it is also possible that the initial presentation of abdominal pain and diarrhea in this case, prior to the diagnosis of lupus nephritis, may have actually been manifestations of CMV enteritis. Such infections have been reported to coincide with the immune dysregulation associated with SLE[13,14].

Interestingly, there have even been reports suggesting that CMV disease itself may induce autoimmune abnormalities[15]. There are a few case reports of acute CMV infection with elevated CMV antibody titers at the time of diagnosis of SLE leading to speculation about a possible role in precipitating lupus activity[16]. There have also been isolated case reports of SLE and Crohn’s disease manifesting simultaneously in the same patient[17], an association which could be attributed to the immunological basis of both diseases. CMV ileitis masquerading as Crohn’s disease has also been reported, with documented mucosal and CT findings consistent with that diagnosis[3]. However, the appearance of a radiographic “string sign” has never been described.

In this case, the persistently low complements and the ileal “string sign”, in light of reports of lupus vasculitis of the GI tract mimicking Crohn’s disease[18], led to a therapeutic quandary. Specifically, it was uncertain whether the patient required intensification of his immunosuppression regimen for presumed vasculitis, or whether discontinuation of immunosuppression and concurrent antibiotic therapy was indicated. Given the well-documented infectious risks of therapies in both lupus and Crohn’s disease, it was decided, despite decreasing complements and continued intractable diarrhea, to defer further immunosuppression pending definitive diagnosis of the underlying ileal pathology. This decision may have saved the patient from potentially catastrophic enhancement of his immunosuppression.

It is instructive to clinicians to be made aware of a rare complication of this common infection in an increasing number of potentially at-risk patients. A negative routine workup in a lupus nephritis patient with acute abdominal pain and diarrhea should provoke a high index of suspicion for occult CMV infection of the GI tract. Such symptoms may also result from mesenteric lupus vasculitis or from a manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease. Since morbidity increases with delay in initiation of effective therapy in all cases, early diagnosis and definitive treatment is vital for a favorable outcome. This case also raises the question in lupus patients as to whether CMV antigenemia and/or polymerase chain reaction for CMV DNA should be done routinely before initiating immunosuppression. The question whether empiric antiviral prophylaxis should be given to CMV seropositive patients remains unanswered.

Peer reviewer: Hitoshi Asakura, Director, Emeritus Professor, International Medical Information Center, Shinanomachi Renga Bldg. 35, Shinanomachi, Shinjukuku, Tokyo 160-0016, Japan

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Yin DH

| 1. | Baroco AL, Oldfield EC. Gastrointestinal cytomegalovirus disease in the immunocompromised patient. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008;10:409-416. |

| 2. | Rafailidis PI, Mourtzoukou EG, Varbobitis IC, Falagas ME. Severe cytomegalovirus infection in apparently immunocompetent patients: a systematic review. Virol J. 2008;5:47. |

| 3. | Ryu KH, Yi SY. Cytomegalovirus ileitis in an immunocompetent elderly adult. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5084-5086. |

| 4. | Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available from: URL: http:www.cdc.gov/cmv/facts.htm. Last Modified: November 3, 2008. |

| 5. | Page MJ, Dreese JC, Poritz LS, Koltun WA. Cytomegalovirus enteritis: a highly lethal condition requiring early detection and intervention. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:619-623. |

| 6. | Houssiau FA, Vasconcelos C, D'Cruz D, Sebastiani GD, Garrido Ed Ede R, Danieli MG, Abramovicz D, Blockmans D, Mathieu A, Direskeneli H. Immunosuppressive therapy in lupus nephritis: the Euro-Lupus Nephritis Trial, a randomized trial of low-dose versus high-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2121-2131. |

| 7. | Tsushima Y, Uozumi Y, Yano S. Reversible thickening of the bowel and urinary bladder wall in systemic lupus erythematosus: a case report. Radiat Med. 1996;14:95-97. |

| 8. | Yoshihara S, Fukuma N, Masago R. [Cytomegalovirus infection associated with immunosuppressive therapy in collagen vascular diseases]. Ryumachi. 1999;39:740-748. |

| 9. | Mori T, Kameda H, Ogawa H, Iizuka A, Sekiguchi N, Takei H, Nagasawa H, Tokuhira M, Tanaka T, Saito Y. Incidence of cytomegalovirus reactivation in patients with inflammatory connective tissue diseases who are under immunosuppressive therapy. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1349-1351. |

| 10. | Chamberlain RS, Atkins S, Saini N, White JC. Ileal perforation caused by cytomegalovirus infection in a critically ill adult. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:432-435. |

| 11. | Hinnant KL, Rotterdam HZ, Bell ET, Tapper ML. Cytomegalovirus infection of the alimentary tract: a clinicopathological correlation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1986;81:944-950. |

| 12. | Bang S, Park YB, Kang BS, Park MC, Hwang MH, Kim HK, Lee SK. CMV enteritis causing ileal perforation in underlying lupus enteritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2004;23:69-72. |

| 13. | Yoon KH, Fong KY, Tambyah PA. Fatal cytomegalovirus infection in two patients with systemic lupus erythematosus undergoing intensive immunosuppressive therapy: role for cytomegalovirus vigilance and prophylaxis? J Clin Rheumatol. 2002;8:217-222. |

| 14. | Ramos-Casals M, Cuadrado MJ, Alba P, Sanna G, Brito-Zerón P, Bertolaccini L, Babini A, Moreno A, D'Cruz D, Khamashta MA. Acute viral infections in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: description of 23 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2008;87:311-318. |

| 15. | Drew WL, Lalezari JP. Cytomegalovirus: disease syndromes and treatment. Curr Clin Top Infect Dis. 1999;19:16-29. |

| 16. | Hayashi T, Lee S, Ogasawara H, Sekigawa I, Iida N, Tomino Y, Hashimoto H, Hirose S. Exacerbation of systemic lupus erythematosus related to cytomegalovirus infection. Lupus. 1998;7:561-564. |

| 17. | Buchman AL, Wilcox CM. Crohn's disease masquerading as systemic lupus erythematosus. South Med J. 1995;88:1081-1083. |

| 18. | Gladman DD, Ross T, Richardson B, Kulkarni S. Bowel involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus: Crohn's disease or lupus vasculitis? Arthritis Rheum. 1985;28:466-470. |