Published online Sep 7, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4204

Revised: August 3, 2009

Accepted: August 10, 2009

Published online: September 7, 2009

Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma (SEF) is a rare and distinct variant of fibrosarcoma, composed of epithelioid tumor cells arranged in strands, nests, cords, or sheets embedded within a sclerotic collagenous matrix. We report a 39-year-old man with SEF of the liver, which infiltrated the inferior vena cava (IVC). The SEF of the liver was successfully resected, and the infiltrated IVC was also removed together with the liver tumor. Histopathological examination of the tumor showed typical histopathology of SEF. Immunohistochemically, the tumor was positive for vimentin. Recurrence was noted 7 mo after surgery. After chemotherapy, the recurrent tumor was resected surgically, and histopathological examination showed similar findings to those of the primary tumor. To our knowledge, this is the first report of SEF of the liver with tumor invasion of the IVC.

- Citation: Tomimaru Y, Nagano H, Marubashi S, Kobayashi S, Eguchi H, Takeda Y, Tanemura M, Kitagawa T, Umeshita K, Hashimoto N, Yoshikawa H, Wakasa K, Doki Y, Mori M. Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma of the liver infiltrating the inferior vena cava. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(33): 4204-4208

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i33/4204.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.4204

Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma (SEF) is a rare and poorly defined variant of fibrosarcoma, first described by Meis-Kindblom et al[1] in 1995[2-4]. It is a mesenchymal neoplasm characterized histopathologically by a predominant population of epithelioid cells arranged in strands, nests, and sheets, embedded in a fibrotic and extensively hyalinized stroma. Although the SEF belongs to the low-grade sarcoma group of neoplasms, approximately 50% of patients with the tumor develop local recurrence and/or metastases[3-5].

Several investigators have reported cases of SEF arising from various sites such as upper extremities, lower extremities, limb girdles, trunk, and the head and neck area, but there have been no reports of SEF of the liver[1-10]. Recently, we experienced a patient with SEF of the liver with invasion of the inferior vena cava (IVC). Although the SEF in the patient was surgically resected, it recurred after surgery. The recurrent SEF was also surgically resected. In addition to the rarity of the SEF of the liver, the SEF displayed a rare extension pattern of infiltration in the IVC. To our knowledge, there have been no previous reports of such kinds of tumor extension in SEF. In this article, we report the first case of SEF of the liver with invasion of the IVC.

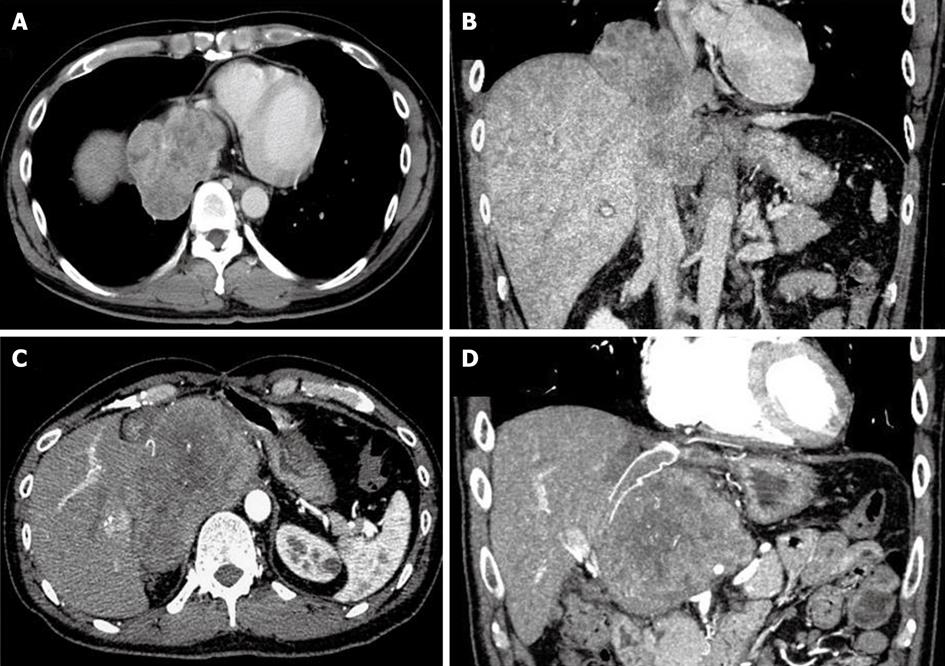

A 39-year-old man presented with the chief complaint of general fatigue and abdominal uncomfortableness. Laboratory findings included no thrombocytopenia and liver enzymes above the normal range (alanine transaminase: 44 U/L, lactate dehydrogenase: 267 U/L, alkaline phosphatase: 412 U/L, and γ-glutamyltranspeptidase: 187 U/L). Hepatitis virus markers and autoantibodies were negative. Tumor markers including protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist II, α-fetoprotein (AFP), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), and carcinoembryonic antigen were all within the normal ranges. Serum soluble interleukin-2 receptor level was not elevated. The patient did not consume alcohol and had no history of exposure to radiation. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a huge liver tumor measuring about 70 mm in diameter located in segment 1 based on Couinaud’s classification, with invasion of the IVC adjacent to the site adjacent to the right atrium[11] (Figure 1A and B). In addition, another liver tumor measuring 18 mm was found in segment 8 on the CT and MRI. Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/CT showed abnormal accumulations in both tumors.

With a preoperative diagnosis of primary malignant liver tumor of unknown origin with invasion of the IVC and possibly intrahepatic metastasis, laparotomy was performed. The huge tumor, which was located mainly in the liver, adhered to the diaphragm, right lower lobe of the lung, and pericardium. The tumor also adhered to the suprahepatic IVC. By using the total hepatic vascular exclusion technique (THVE), extended left hepatectomy with resection of the caudate lobe of the liver was performed. The diaphragm, the right lower lobe of the lung, and the pericardium were resected. Next, after clamping the suprahepatic IVC below the right atrium and the retrohepatic IVC above the renal veins, the adhered IVC wall was removed together with the liver. The resected IVC wall was replaced with an expanded polytetrafluoroethylene graft. Since the tumor in segment 8 was suspicious of intrahepatic metastasis, partial hepatectomy of segment 8 was also performed. No other liver tumors were found during surgery.

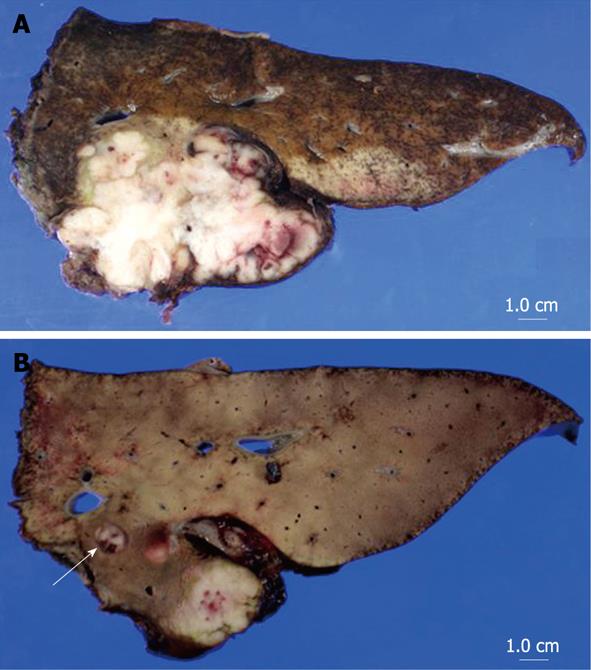

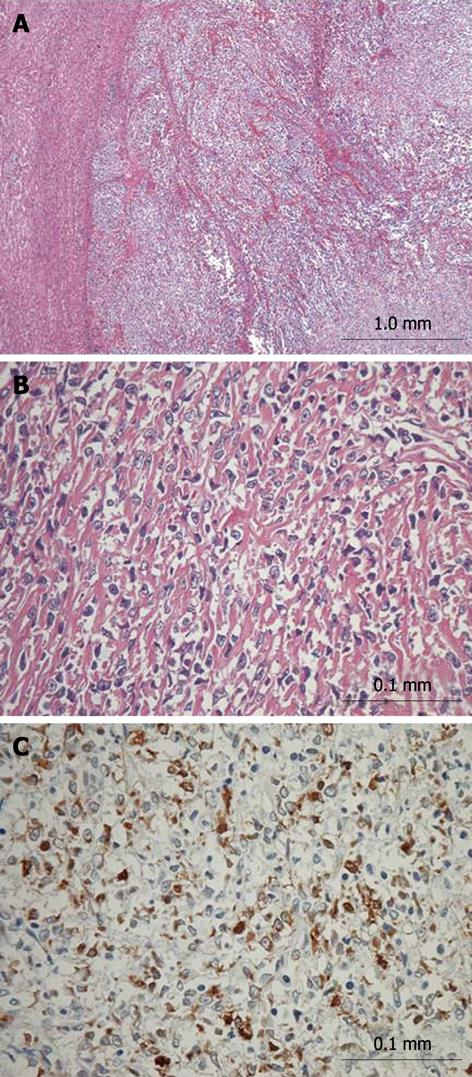

A macroscopic view of the resected tumor was shown in Figure 2. The tumor, measuring 68 mm × 54 mm, was mainly located in segment 1 of the liver. Microscopically, the tumor mainly existed in the liver with invasion into neighboring extrahepatic soft tissue including the wall of the IVC and diaphragm. Moreover, tumor thrombi were identified in the left portal vein and its branches. The tumor consisted of uniformly round or polygonal epithelioid cells with a faintly eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 3A and B). The tumor cells were arranged in strands, nests, cords or sheets and embedded in a heavily hyalinized matrix. The microscopic findings of the tumor in segment 8 were similar to those of the primary tumor, and that tumor was diagnosed as an intrahepatic metastasis. Immunohistochemical staining of the main tumor was positive for vimentin (Dakopatts, Glostrup, Denmark), bcl-2 (Dakopatts), and CD99 (Dakopatts), and was negative for AE1/AE3 (Dakopatts), CAM5.2 (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA), desmin (Dakopatts), epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) (Dakopatts), CD34 (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan), S100, α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (Dakopatts), neuron-specific enolase (Dakopatts), CD56 (Dakopatts), leukocyte common antigen (LCA) (Dakopatts), CD30 (Dakopatts), HMB45 (Dakopatts), AFP (Dakopatts), and CA19-9 (Zymed Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, CA) (Figure 3C). The MIB-1 labeling index (Dakopatts) was 30%. Moreover, cytogenetic analysis did not show t (X; 18) chromosomal translocation, which is frequently observed in synovial sarcoma[12,13]. Based on the results of histopathological examination, cytogenetic analysis, and immunohistochemical patterns, the tumor was finally diagnosed as SEF. Although the tumor was associated with invasion to the wall of the IVC and diaphragm, the most part of the tumor existed in segment 1 of the liver. Moreover, tumor thrombi were identified in the right portal vein and its peripheral branches, and intrahepatic metastases, which were frequently seen in the primary liver malignant tumor. Therefore, the SEF probably originated from the liver. The resection margins were free of tumor. The noncancerous area of the liver was histologically normal. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course and was discharged from the hospital 24 d after surgery.

Seven months after surgery, the patient complained of back pain. CT examination showed recurrent SEF in the extrahepatic retroperitoneal tissue (Figure 1C and D). Systemic chemotherapy consisting of adriamycin and ifosfamide was applied. Close follow-up showed arrest of tumor growth and no new metastatic lesions within the first 3 mo. Subsequently, laparotomy was performed for the excision of the recurrent tumor 12 mo after the initial surgery. The recurrent tumor, located in the retroperitoneal tissue and adherent to the remnant liver, also infiltrated the graft IVC. Using the THVE approach, the tumor was resected with the adherent liver tissue and the infiltrated IVC graft. The resected IVC was again replaced with an expanded polytetrafluoroethylene graft. The microscopic findings of the resected tumor were similar to those of the primary SEF. The immunohistochemical staining patterns of the primary tumor and the recurrent tumor were also similar. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course and was discharged from the hospital 30 d after the surgery.

At the last follow-up examination 6 mo after the second surgery, he remains in good condition, with no evidence of recurrence.

SEF is a rare tumor characterized histopathologically by a predominant population of epithelioid cells arranged in strands, nests, cords, or sheets, which are embedded within a sclerotic collagenous matrix[1-4]. Immunohistochemically, staining for vimentin is positive in all SEF whereas staining for CD34, leukocyte markers, HMB45, CD68, desmin, glial fibrillary acidic protein, and TP53 is negative. Focal and weak immunostaining for EMA, S100 and more rarely for cytokeratins may be seen in a minority of cases.

The histopathological differential diagnosis of SEF generally includes a wide variety of tumors with sclerotic or epithelioid features, and thus immunohistochemical analysis is essential for precise diagnosis of SEF. In the present case, differential diagnosis was challenging for the following reasons. Undifferentiated hepatocellular carcinoma and infiltrating adenocarcinoma should be differentiated from SEF, but immunohistochemical staining for AFP, CAM5.2, and AE1/AE3 was negative in the present case. Synovial sarcoma should also be differentiated from SEF. Cytogenetic identification of t (X: 18), which is found in synovial sarcoma, could differentiate synovial sarcoma from SEF[12,13]. No chromosomal translocation was observed in the present case. Furthermore, smooth muscle neoplasms, such as hyalinized leiomyoma or leiomyosarcoma, frequently resemble SEF histopathologically, but they are characterized by immunohistochemical positivity for α-SMA and desmin. Clear cell sarcoma and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors may need to be distinguished from SEF. However, these tumors are positive for S100 immunostaining. Moreover, sclerosing lymphoma and malignant melanoma of the soft part are also on the list of differential diagnoses, but these tumors are usually positive for LCA and HMB45, respectively, and were negative in our case. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma could be ruled out based on immunonegativity for CD34, and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma could be excluded by the negative result of desmin and absence of rhabdomyoblasts. Moreover, absence of osteroid formation excluded traosseous osteosarcoma in the present case. Thus, taking into consideration not only the histopathological findings but also the results of cytogenetic analysis and immunohistochemical examinations, the tumor was finally diagnosed as SEF.

In reviewing previous reports, SEFs usually arise in the deep soft tissue and are frequently associated with the adjacent fascia or periosteum. Most SEFs are located in the lower extremities and limb girdles, followed by the trunk, upper extremities, and the head and neck area[1-10].

In this case, although the tumor was associated with invasion to the wall of IVC and diaphragm, the most part of the tumor existed in the liver. Moreover, in this case, tumor thrombi and intrahepatic metastases were concurrently identified. These features might suggest that the tumor had originated in the liver. To our knowledge, there have been no reports of SEF originating from the liver.

The etiology of most malignant soft tissue tumors, including SEF, is generally unknown. A recent report reviewed 90 patients with SEF and found no significant gender difference with a mean patient age of 47 years (range, 14-87 years)[5]. The average tumor size at diagnosis is about 8 cm. Several investigators reported previously the association between radiation and occurrence of fibrosarcoma, though our patient had no history of radiation[99,1414].

The established treatment for SEF is complete resection. There is no evidence to support the effect of chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, though these therapies were used in some previous reports[3,10]. As for prognosis, Chow et al[4] reported 57 patients with SEF with a local recurrence rate of 48%, metastasis rate of 60%, and mortality rate of 35%. Moreover, in a study of 16 patients with SEF by Antonescu et al[3], the local recurrence rate, metastasis rate, and mortality rate were 50%, 86% and 57%, respectively[5]. Distant metastasis is reported to be most common in the lung, followed by bone, soft tissue, brain, and lymph nodes[1-5]. These previous reports of poor prognosis suggest that SEF is a clinicopathologically distinct soft tissue tumor with malignant potential although it is categorized as a low-grade neoplasm in the sarcoma group.

In our case, since no distant metastasis was found preoperatively and since complete resection was thought possible, we selected surgical resection although the tumor had extended at the time of surgery into the IVC, in addition to local intrahepatic metastasis. Indeed, we could completely resect the tumor macroscopically, but the tumor recurred postoperatively. It is quite possible that malignant cells remained at the tumor bed after the resection despite our careful endeavor. Alternatively, considering the high recurrence rate of SEF reported previously, it is also possible that malignant cells might have already exfoliated from the tumor extending to IVC and presumably reached other organs before the resection. Thus, when surgical resection is selected for SEF, perioperative chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, in addition to macroscopic complete resection, may be necessary to prevent recurrence, though there is no established effective and standardized regimen of chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. To clarify the effect of perioperative chemoradiotherapy, in addition to surgical resection, further study with a larger number of SEF cases treated perioperatively is needed.

| 1. | Meis-Kindblom JM, Kindblom LG, Enzinger FM. Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma. A variant of fibrosarcoma simulating carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:979-993. |

| 2. | Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F. World Health Organisation classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. Lyon: IARC Press 2002; 106-107. |

| 3. | Antonescu CR, Rosenblum MK, Pereira P, Nascimento AG, Woodruff JM. Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma: a study of 16 cases and confirmation of a clinicopathologically distinct tumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:699-709. |

| 4. | Chow LT, Lui YH, Kumta SM, Allen PW. Primary sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma of the sacrum: a case report and review of the literature. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:90-94. |

| 5. | Ossendorf C, Studer GM, Bode B, Fuchs B. Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma: case presentation and a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:1485-1491. |

| 6. | Bilsky MH, Schefler AC, Sandberg DI, Dunkel IJ, Rosenblum MK. Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcomas involving the neuraxis: report of three cases. Neurosurgery. 2000;47:956-959; discussion 959-960. |

| 7. | Abdulkader I, Cameselle-Teijeiro J, Fraga M, Caparrini A, Forteza J. Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma primary of the bone. Int J Surg Pathol. 2002;10:227-230. |

| 8. | Battiata AP, Casler J. Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma: a case report. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2005;114:87-89. |

| 9. | Massier A, Scheithauer BW, Taylor HC, Clark C, Llerena L. Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma of the pituitary. Endocr Pathol. 2007;18:233-238. |

| 10. | Frattini JC, Sosa JA, Carmack S, Robert ME. Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma of the cecum: a radiation-associated tumor in a previously unreported site. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1825-1828. |

| 12. | Clark J, Rocques PJ, Crew AJ, Gill S, Shipley J, Chan AM, Gusterson BA, Cooper CS. Identification of novel genes, SYT and SSX, involved in the t(X;18)(p11.2;q11.2) translocation found in human synovial sarcoma. Nat Genet. 1994;7:502-508. |

| 13. | Gisselsson D, Andreasson P, Meis-Kindblom JM, Kindblom LG, Mertens F, Mandahl N. Amplification of 12q13 and 12q15 sequences in a sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1998;107:102-106. |