Published online Sep 7, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4193

Revised: August 6, 2009

Accepted: August 13, 2009

Published online: September 7, 2009

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are at increased risk of colorectal malignancies. Adenocarcinoma is the commonest type of colorectal neoplasm associated with ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease, but other types of epithelial and non-epithelial tumors have also been described in inflamed bowel. With regards to non-epithelial malignancies, lymphomas and sarcomas represent the largest group of tumors reported in association with IBD, especially in immunosuppressed patients. Carcinoids and in particular neuroendocrine neoplasms other than carcinoids (NENs) are rare tumors and are infrequently described in the setting of IBD. Thus, this association requires further investigation. We report two cases of neoplasms arising in mild left-sided UC with immunohistochemical staining for neuroendocrine markers: a large cell and a small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the rectum. The two patients were different in age (35 years vs 77 years) and disease duration (11 years vs 27 years), and both had never received immunosuppressant drugs. Although the patients underwent regular endoscopic and histological follow-up, the two neoplasms were locally advanced at diagnosis. One of the two patients developed multiple liver metastases and died 15 mo after diagnosis. These findings confirm the aggressiveness and the poor prognosis of NENs compared to colorectal adenocarcinoma. While carcinoids seem to be coincidentally associated with IBD, NENs may also arise in this setting. In fact, long-standing inflammation could be directly responsible for the development of pancellular dysplasia involving epithelial, goblet, Paneth and neuroendocrine cells. It has yet to be established which IBD patients have a higher risk of developing NENs.

- Citation: Grassia R, Bodini P, Dizioli P, Staiano T, Iiritano E, Bianchi G, Buffoli F. Neuroendocrine carcinomas arising in ulcerative colitis: Coincidences or possible correlations? World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(33): 4193-4195

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i33/4193.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.4193

It is well recognized that ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) predispose to the development of colorectal adenocarcinoma (CRC). The duration and the anatomic extent of the disease have been shown to be independent risk factors for the development of CRC[1]. Thus, cancer is infrequently encountered when disease duration is less then 8-10 years, thereafter the risk rises at approximately 0.5%-1% per year[2]. Additional risk factors are the presence of primary sclerosing cholangitis and a family history of CRC. Younger age at diagnosis and the degree of endoscopic and histological activity may also play an important role[1]. A comprehensive meta-analysis of all published studies reporting CRC risk in UC up to 2001 showed that the risk for any patients with colitis was 2% at 10 years, 8% at 20 years and 18% after 30 years of disease[3].

Based on this evidence, guidelines for screening and surveillance of asymptomatic CRC in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have been developed to detect either dysplasia or early cancer at a surgically curable stage, and to reduce CRC related mortality[1,2].

While adenocarcinoma is the most common colorectal epithelial malignancy associated with UC and CD, other types of carcinomas such as squamous cell carcinoma, small cell carcinoma and “hepatoid” carcinoma have been described in inflamed bowel. With regards to non-epithelial malignancies, lymphomas and sarcomas represent the largest group of tumors reported in association with IBD, especially in immunosuppressed patients[4].

Carcinoid tumors and neuroendocrine neoplasms other than carcinoids (NENs) may also be associated with UC and CD of the colon based on the finding of increased numbers of neuroendocrine cells in inflamed mucosa, suggesting that long-standing inflammation is directly responsible for the development of this kind of neoplasia[4].

NENs of the colon and rectum are rare tumors, and are infrequently described in the setting of IBD. Here we report two cases of NENs arising in UC.

A 35-year-old man with an 11-year history of mild distal colitis was admitted due to constipation, proctorrhagia, tenesmus and perianal pain. Twelve months before admission, a surveillance colonoscopy with biopsy showed endoscopic remission of the inflammatory disease. His treatment consisted of oral mesalamine 2.4 g/d and he had never received immunosuppressant drugs.

A second colonoscopy indicated a rectal substenosis caused by a large ulcerated mass originating about 2 cm above the anorectal junction, with a proximal extension of about 4 cm.

Histological examination showed a high grade large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for chromogranin, synaptophysin, cytokeratin 7 and chorioallantoic membrane 5.2. Laboratory findings including chromogranin A and neuron-specific enolase were negative.

A staging computed tomography scan and somatostatin receptors imaging were negative for further spread of the tumor. The patient underwent a low anterior colorectal resection and distal rectal mucosectomy with colo-anal anastomosis and loop ileostomy. A definitive pathological investigation confirmed the previous histological findings, and the proliferative marker Mib1/Ki67 was positive in about 50% of the neoplastic cells. The TNM stage was pT3R1pN217/30M0G3. He was treated with adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy with cisplatin and etoposide. One year after surgery, multiple liver metastases were observed. The patient died 15 mo after diagnosis.

A 77-year-old man presented with bloody diarrhea, anorectal pain, mild anemia and a 3 kg weight loss. The patient had a 27-year history of left-sided colitis with mild activity. Ten months before admission, a surveillance colonoscopy with biopsy showed mild left-sided inflammation. He was receiving oral mesalamine 2.4 g/d.

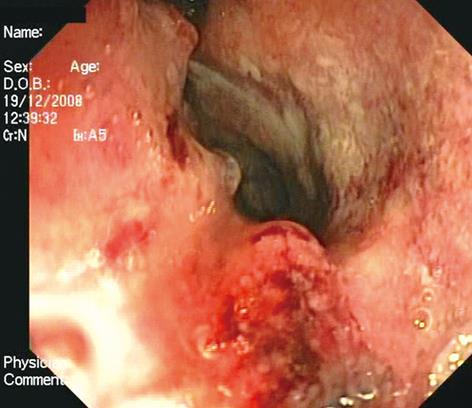

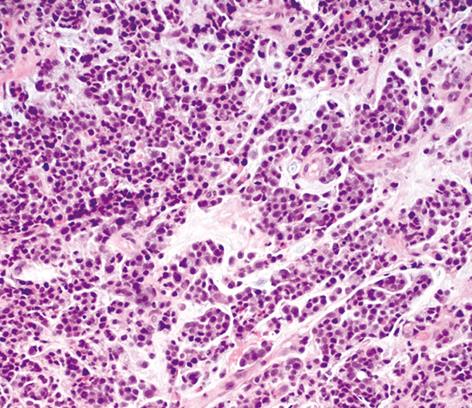

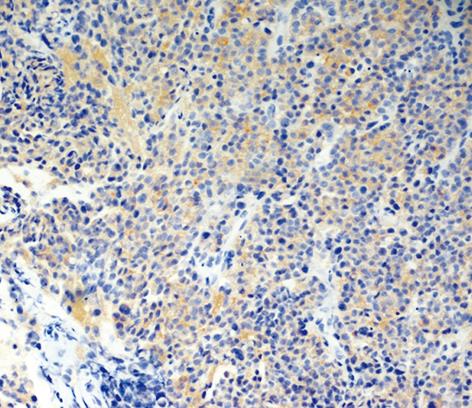

Another colonoscopy was performed, which showed a large circular neoplasm of about 5 cm in length, 3 cm above the anorectal junction (Figure 1). Histological examination with immunohistochemical analysis excluded adenocarcinoma. A tumor with neuroendocrine differentiation and strong staining for synaptophysin was observed and a high grade small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma was diagnosed (Figures 2 and 3). The proliferative marker Mib1/Ki67 was positive in about 90% of the neoplastic cells. MR scanning and somatostatin receptors imaging were negative for further neoplastic localizations. The patient is scheduled to receive neo-adjuvant radiotherapy.

DISCUSSION

The reported incidence of NENs is between 0.1% and 3.9% of all colorectal malignancies. Bernick et al[5], at New York Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, reported an incidence of 0.6% in colon and rectal cancers.

NENs are subdivided on the basis of cytological-histological features and immunohistochemical findings into small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (SCNC) and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNC)[5]. The criteria for separating small cell from large cell variants are similar to those proposed for the classification of pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors[6]. SCNCs resemble their pulmonary homonyms, having minimal cytoplasm, fusiform cell shape, fine granular chromatin, small or absent nucleoli, and nuclear moulding. LCNCs are characterized by cells with more cytoplasm, a round or polygonal cell shape, prominent nucleoli, and a coarser chromatin pattern.

While the diagnosis of SCNC does not necessitate immunohistochemical documentation of neuroendocrine differentiation, the diagnosis of LCNC requires positive immunohistochemical staining for one of the three neuroendocrine markers (chromogranin, synaptophysin and neuron-specific enolase) in at least 10% of tumor cells[5].

Even though they are extremely rare, it is important to recognize NENs pathologically, since they have a particularly poor prognosis compared to colorectal adenocarcinoma. NENs shows a high rate of liver metastasis (50%) and the reported 1-year survival rate is about 40%[5]. Thus, patients could benefit from treatment with alternative cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents[6].

There have been reports of neuroendocrine tumors associated with UC, but many of these tumors are carcinoids, often well-differentiated and clinical indolent, and are found incidentally at a different site from dysplastic areas after surgery for IBD[7]. Greenstein et al[7] believe that this association is coincidental, particularly since there are no significant demographic or clinicopathological differences between the carcinoids that occur in patients with and without IBD. Furthermore, the same authors point out that neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia, probably due to a trophic role of these cells in epithelial re-growth, is not itself an established association with carcinoids.

Sigel et al[8] reported the only series of NENs other than carcinoids arising in 14 IBD patients (eight CD; six UC). Similar to our findings, they observed that all the tumors arose in areas involved by IBD, and six of the 14 neoplasms affected the rectum. The NENs were well differentiated in 11 cases and poorly differentiated in three cases; two of these three patients died at 3 and 11 mo after tumor excision.

These authors suggested that neuroendocrine differentiation, different to carcinoids, might evolve from multipotential cells in dysplastic epithelium. This was based on their findings that dysplasia was found in adjacent mucosa in more than one-third of cases[8].

Our cases confirm the aggressive biological behavior and poor response to chemotherapy of NENs compared to colorectal adenocarcinoma. Both NENs in these patients arose in mild left-sided UC, however, the patients were different in age (35 years vs 77 years) and disease duration (11 years vs 27 years). This raises the question as to whether these carcinomas represent an incidental finding in the background of IBD or if there is a real, although rare, association between IBD and these tumors.

The hypothesis of a pancellular dysplasia involving epithelial, goblet, Paneth and neuroendocrine cells in chronic inflamed mucosa cannot be confirmed from the few published case reports[8-11]. In addition, the differences in terms of duration, extension, histological and endoscopic activity of the underlying IBD in our and other reported cases[8-11] do not allow the identification of a subgroup of patients at risk.

| 1. | Itzkowitz SH, Present DH. Consensus conference: Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:314-321. |

| 2. | Eaden JA, Mayberry JF. Guidelines for screening and surveillance of asymptomatic colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2002;51 Suppl 5:V10-V12. |

| 3. | Eaden JA, Abrams KR, Mayberry JF. The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2001;48:526-535. |

| 4. | Wong NA, Harrison DJ. Colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis-recent advances. Histopathology. 2001;39:221-234. |

| 5. | Bernick PE, Klimstra DS, Shia J, Minsky B, Saltz L, Shi W, Thaler H, Guillem J, Paty P, Cohen AM. Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:163-169. |

| 6. | Vortmeyer AO, Lubensky IA, Merino MJ, Wang CY, Pham T, Furth EE, Zhuang Z. Concordance of genetic alterations in poorly differentiated colorectal neuroendocrine carcinomas and associated adenocarcinomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1448-1453. |

| 7. | Greenstein AJ, Balasubramanian S, Harpaz N, Rizwan M, Sachar DB. Carcinoid tumor and inflammatory bowel disease: a study of eleven cases and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:682-685. |

| 8. | Sigel JE, Goldblum JR. Neuroendocrine neoplasms arising in inflammatory bowel disease: a report of 14 cases. Mod Pathol. 1998;11:537-542. |

| 9. | Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 28-2000. A 34-year-old man with ulcerative colitis and a large perirectal mass. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:794-800. |

| 10. | van der Woude CJ, van Dekken H, Kuipers EJ. Bleeding - not always a sign of relapse of long-standing colitis. Endoscopy. 2007;39 Suppl 1:E121-E122. |

| 11. | Rubin A, Pandya PP. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the rectum associated with chronic ulcerative colitis. Histopathology. 1990;16:95-97. |