Published online Aug 21, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3950

Revised: July 10, 2009

Accepted: July 17, 2009

Published online: August 21, 2009

A preduodenal portal vein (PDPV) is known to be a rare cause of duodenal stenosis. We treated a 22-year-old male patient with malnutrition as a result of PDPV and a previously performed operation for scoliosis, who showed an improvement in quality of life after being treated with a combination of nutritional support and surgery. The patient with PDPV had been admitted to our department with duodenal stenosis, ranging from the first to third portions. He had suffered from vomiting since 1 year of age, and he developed malnutrition during the last 6-mo period after orthopedic surgery for scoliosis. The stenosis was related to both the PDPV and the previously performed operation for scoliosis. After receiving nutritional support for 6 mo, a gastrojejunostomy with Braun’s anastomosis for the first portion and a duodenojejunostomy for the second and third portions were performed. The postoperative course was almost uneventful. Three months later, he was discharged and able to attend university. In patients with widespread duodenal stenosis, there may be a complicated cause, such as PDPV and duodenal stretching induced by previous spinal surgery.

- Citation: Masumoto K, Teshiba R, Esumi G, Nagata K, Nakatsuji T, Nishimoto Y, Yamaguchi S, Sumitomo K, Taguchi T. Duodenal stenosis resulting from a preduodenal portal vein and an operation for scoliosis. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(31): 3950-3953

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i31/3950.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.3950

Preduodenal portal vein (PDPV) is a rare congenital anomaly which was first described by Knight in 192l[1]. Clinically, 50% of the patients present with symptoms related to intestinal obstruction, but only in a few is the obstruction directly caused by the PDPV[2–4]. In the majority of cases, the obstruction is thought to be caused by associated anomalies such as duodenal diaphragm, intestinal malrotation, and annular pancreas. In the remaining 50%, PDPV is asymptomatic and diagnosed incidentally on preoperative investigation or during surgery for other diseases[2–4]. Patients with symptoms directly associated with PDPV or resulting from associated anomalies often require correction of the intestinal obstruction[2–5].

Scoliosis is a well known anomaly in the pediatric orthopedic field. In patients with severe scoliosis, a surgical correction is often needed. The hallmark of surgical treatment is thought to be early intervention before the development of large curvatures[6]. Recent orthopedic surgery for scoliosis has evolved to include the routine use of spinal instrumentation to achieve a good result.

No reports have been published regarding patients with PDPV associated with severe scoliosis. We experienced one male patient with malnutrition resulting from PDPV and a previously performed operation for scoliosis. An improvement in the quality of life (QOL) was found after being treated with a combination of a gastrojejunostomy, with both Braun’s anastomosis and a side-to-side anastomosis between the duodenal second portion and jejunum, and nutritional support. Therefore, we herein report and discuss the clinical course of this patient and his treatment.

A 22-year-old male patient with PDPV presented with duodenal stenosis, ranging from the first to the second portions. Frequent vomiting had occurred at 1 year of age. Therefore, fundoplication had been performed at 2 years of age in another hospital. However, he had occasionally suffered from vomiting since the fundoplication. In addition, he gradually developed severe scoliosis over time. Therefore, he underwent surgery twice for scoliosis at 21 and 22 years of age. After the orthopedic operations, he developed malnutrition because of severe vomiting during a 6-mo period. In another hospital, the cause of the vomiting was investigated, and found to be the result of widespread duodenal stenosis.

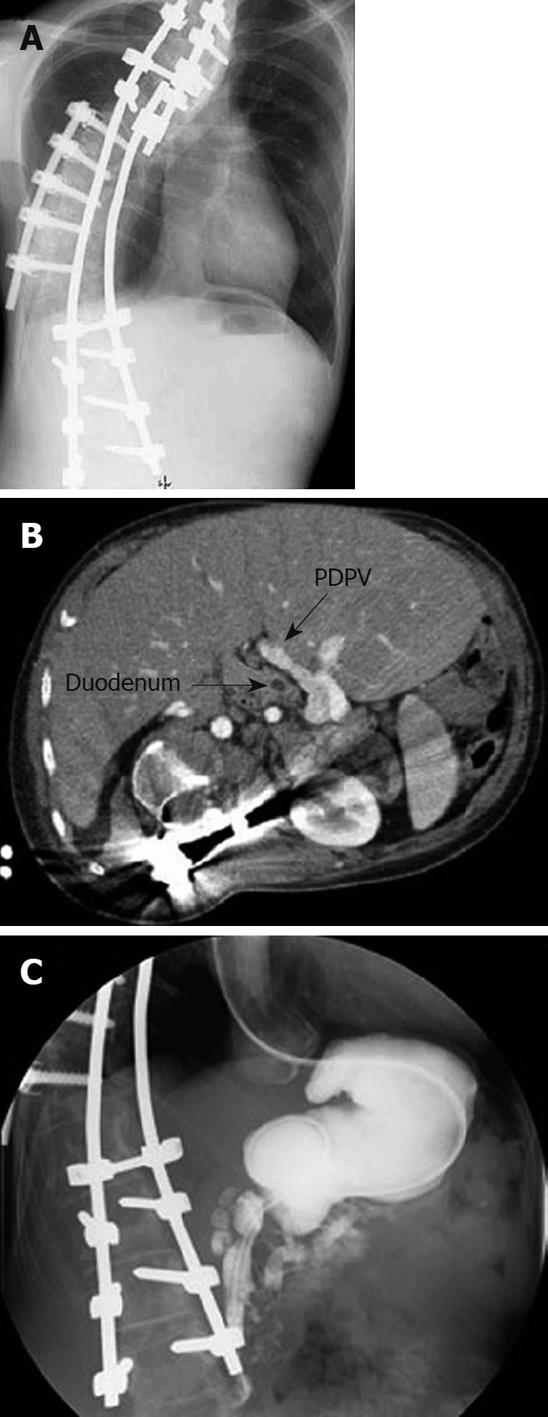

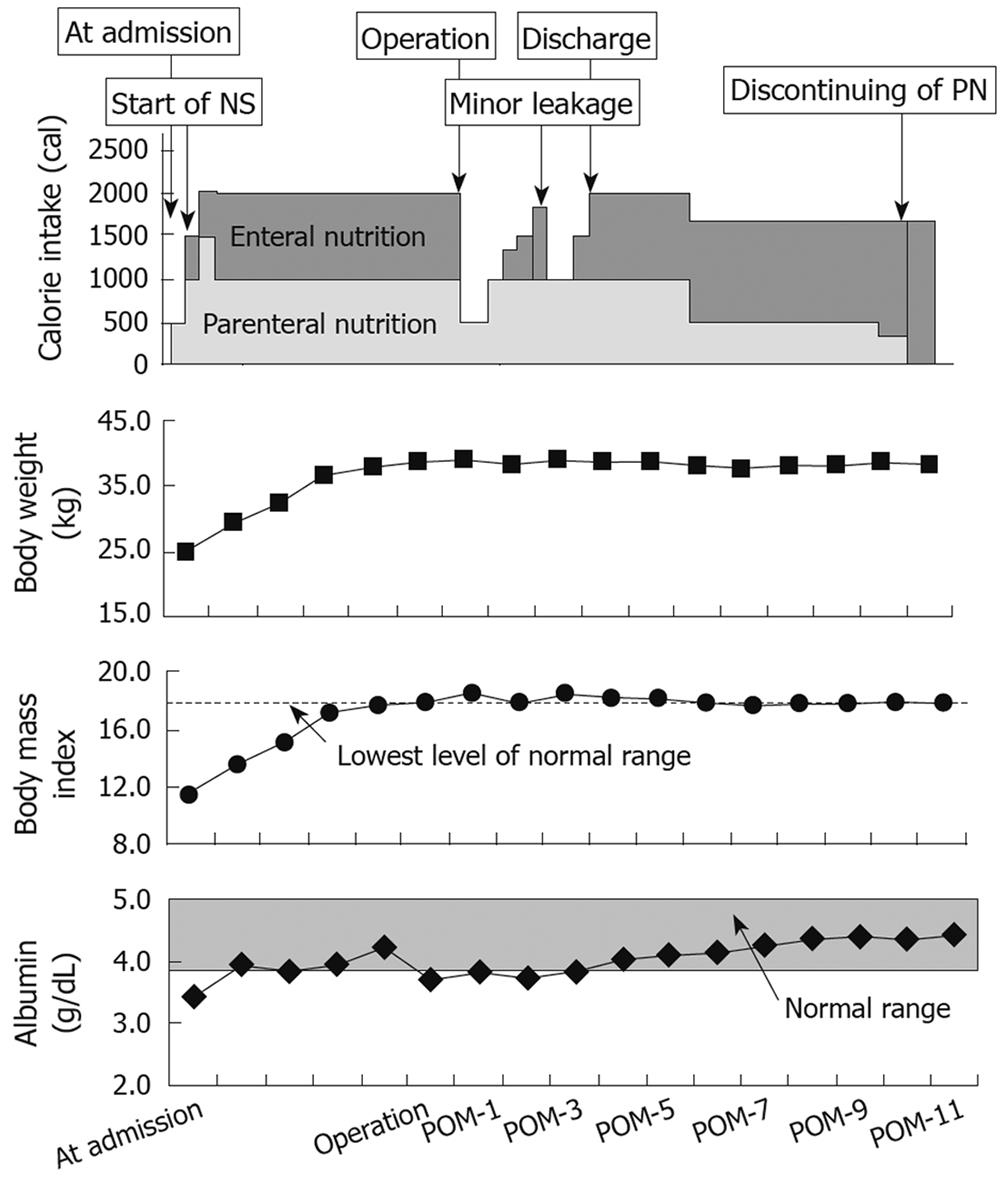

On admission to our department, an X-ray film showed a spine with a large curve to the right side although it was corrected by previous orthopedic surgery (Figure 1A). Abdominal computerized tomography (Figure 1B) and a gastrointestinal contrast study (Figure 1C) revealed that the stenosis was associated with both the PDPV and the previously performed operation for scoliosis. In addition, his nutritional condition at admission was extremely poor (body mass index: 11.4). Furthermore, he also had diabetes associated with dysfunction of Vater’s sphincter. We therefore introduced nutritional support using both parenteral and enteral nutrition by jejunal feeding tube at first. Two months later, the blood sugar was well controlled by insulin therapy. During nutritional support with insulin therapy for 6 mo, his nutritional condition gradually improved (Figure 2). Six months later, his nutritional condition was observed to have returned to the normal level for his age (body mass index: 18.2, Figure 2).

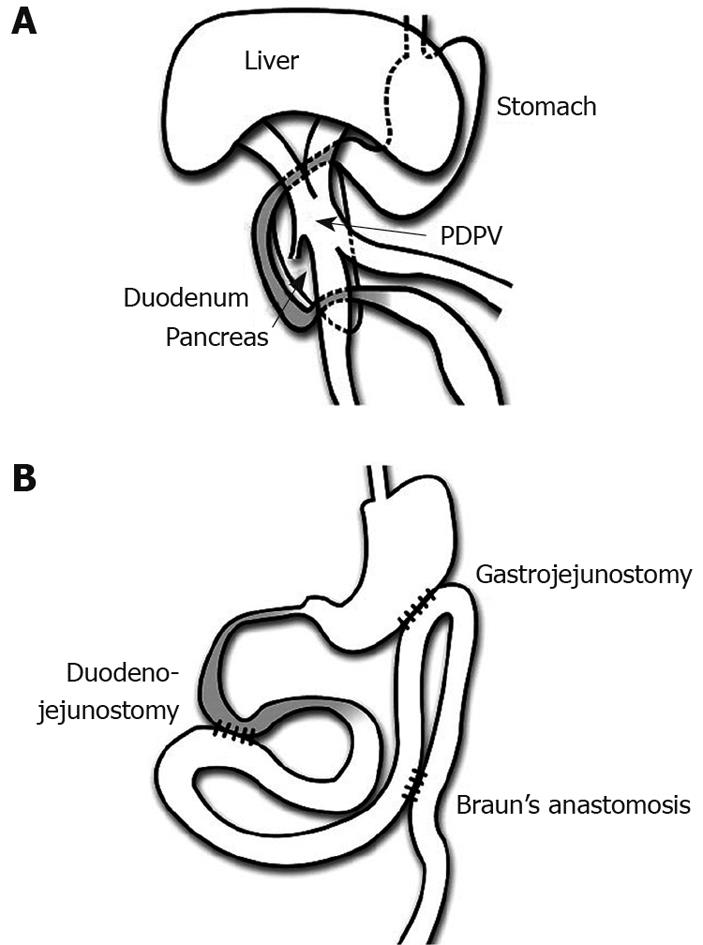

Thereafter, an operation was performed. The operative findings showed that the PVPD had induced the severe stenosis of the duodenal first portion, and that the stenosis widely ranging from the second to third portions was a result of stretching by the corrected spine (Figure 3A). No intestinal malrotation was found. The liver was confirmed to be a symmetrical liver. The head of the pancreas was found to be attached to the stenosis of the first duodenal portion. However, the pancreas did not surround any portions of the duodenum. Although the second portion was mildly dilated after performing mobilization of the duodenal second portion, neither the first nor third duodenal portion was dilated (Figure 3B). Therefore, a gastrojejunostomy with Braun’s anastomosis was selected and performed (Figure 3B). In addition, a side-to-side anastomosis between the duodenal second portion and jejunum was performed to allow smooth passage of the duodenal contents (Figure 3B).

The postoperative course was uneventful except for slight leakage at the site of anastomosis. Regarding his diabetes, he required insulin therapy for the control of blood sugar. The postoperative contrast study showed that duodenal passage in the second portion improved and that most of the contents in the stomach flowed smoothly into the connected jejunum through the gastrojejunostomy. Two months later, he could eat a normal volume of solid food by mouth (Figure 2). Three months later, he was discharged, using both feeding by mouth and home parenteral nutrition with insulin therapy, and was again able to attend university (Figure 2). Seven months after discharge, he no longer required home parenteral nutrition. Unfortunately, an improvement in his diabetes was not observed after the operation and therefore he has needed to continue insulin therapy.

In general, a PDPV without associated anomalies may be the cause of duodenal stenosis in the first or second portion if symptoms related to PDPV occur[1234578]. Therefore, in such patients, an operation including duodenoduodenostomy, is thought to be required for the smooth passage of duodenal contents[1–578]. However, in this patient with PDPV, the stenosis ranged from the first to the third portions of the duodenum. This may be why duodenal stenosis in this patient was also associated with severe scoliosis. He had needed an operation for severe scoliosis but the surgery was not thought to be good for duodenal passage because the duodenum was stretched longitudinally to the spinal axis. After the orthopedic operation, his symptoms had further deteriorated. The first portion of the duodenum was thought to be anchored to both the thick pedicle of the PDPV and the head of the pancreas, and stretched to the hepatic side before the orthopedic operation. Therefore, the orthopedic operation may have induced excessive stretching of the duodenum, resulting in the duodenal stenosis, ranging from the second to third portions, in addition to the stenosis of first portion arising from the PDPV.

In this patient, the long-term symptoms related to PDPV, including frequent vomiting, induced malnutrition. In addition, the duodenal stretching after the orthopedic operation also contributed to the malnutrition. In general, if the severe symptoms are thought to be related to PDPV, duodenoduodenostomy is performed first[178]. However, in this patient, we preceded surgery with the recovery of his nutritional condition using both parenteral and enteral nutrition, since his nutritional condition had been very severe at admission. Although the time required for the nutritional recovery was long, the operation for the duodenal stenosis was performed smoothly, leading to a good postoperative clinical course. Therefore, in a specific case with severe malnutrition as in this report, nutritional support may precede the operation for severe duodenal stenosis.

In cases where duodenoduodenostomy is performed for duodenal stenosis resulting from PDPV, recent studies recommend the loose overbridging duodenoduodenostomy in order not to compress the blood flow of the portal vein[9]. In this patient, we could not perform the loose overbridging duodenoduodenostomy for stenosis of the duodenal first portion because the stenosis was widespread. Therefore, a gastrojejunostomy with Braun’s anastomosis was performed. In addition, a side-to-side anastomosis between the duodenal second portion and the jejunum was performed to allow smooth passage of the duodenal contents, including the pancreatic juice and bile, because Kocher’s duodenal mobilization did not result in enough improvement of the stenosis ranging from the second to third portions. As no patient with a clinical course similar to our patient had been reported in the literature, we were uncertain which operations were the best choice for this patient. However, based on the postoperative clinical course in our patient, the operations we performed resulted in an improvement in the patient’s QOL. Therefore, such a combination of operations is thought to be one choice for severe widespread duodenal stenosis.

| 2. | Ooshima I, Maruyama T, Ootsuki K, Ozaki M. Preduodenal portal vein in the adult. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1998;5:455-458. |

| 3. | Esscher T. Preduodenal portal vein--a cause of intestinal obstruction? J Pediatr Surg. 1980;15:609-612. |

| 4. | Mordehai J, Cohen Z, Kurzbart E, Mares AJ. Preduodenal portal vein causing duodenal obstruction associated with situs inversus, intestinal malrotation, and polysplenia: A case report. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:E5. |

| 5. | Choi SO, Park WH. Preduodenal portal vein: a cause of prenatally diagnosed duodenal obstruction. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:1521-1522. |

| 6. | Weinstein SL, Dolan LA, Cheng JC, Danielsson A, Morcuende JA. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Lancet. 2008;371:1527-1537. |

| 7. | Talus H, Roohipur R, Depaz H, Adu AK. Preduodenal portal vein causing duodenal obstruction in an adult. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:552-553. |

| 8. | John AK, Gur U, Aluwihare A, Cade D. Pre duodenal portal vein as a cause of duodenal obstruction in an adult. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74:1032-1033. |

| 9. | Ohno K, Nakamura T, Azuma T, Yoshida T, Hayashi H, Nakahira M, Nishigaki K, Kawahira Y, Ueno T. Evaluation of the portal vein after duodenoduodenostomy for congenital duodenal stenosis associated with the preduodenal superior mesenteric vein, situs inversus, polysplenia, and malrotation. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:436-439. |