Published online Aug 14, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3827

Revised: June 24, 2009

Accepted: July 1, 2009

Published online: August 14, 2009

Mesenteric panniculitis is a rare, benign and chronic fibrosing inflammatory disease that affects the adipose tissue of the mesentery of the small intestine and colon. The specific etiology of the disease is unknown. The diagnosis is suggested by computed tomography and is usually confirmed by surgical biopsies. Treatment is empirical and based on a few selected drugs. Surgical resection is sometimes attempted for definitive therapy, although the surgical approach is often limited. We report two cases of mesenteric panniculitis with two different presentations and subsequently varying treatment regimens. Adequate response was obtained in both patients. We present details of these cases as well as a literature review to compare various presentations, etiologies and potential treatment modalities.

- Citation: Issa I, Baydoun H. Mesenteric panniculitis: Various presentations and treatment regimens. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(30): 3827-3830

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i30/3827.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.3827

Mesenteric panniculitis is an acute benign fibrosing and inflammatory condition that involves the adipose tissue of the mesentery. It was first described by Jura in 1924 as “retractile mesenteritis” and further labeled as “mesenteric panniculitis” by Odgen later in the 1960s. Currently, it has several names: sclerosing mesenteritis, mesenteric lipodystrophy, mesenteric sclerosis, retractile mesenteritis, mesenteric Weber-Christian disease, liposclerotic mesenteritis, lipomatosis and lipogranuloma of the mesentery[1]. It can be categorized according to three pathological changes: chronic nonspecific inflammation, fat necrosis and fibrosis[2]. This varied terminology has caused considerable confusion, but the condition can now be evaluated as a single disease with two pathological subgroups. If inflammation and fat necrosis predominate over fibrosis, the condition is known as mesenteric panniculitis, and when fibrosis and retraction predominate, the result is retractile mesenteritis. The overall presence of some degree of fibrosis makes the pathological term sclerosing mesenteritis more accurate in most cases[3].

A 68-year-old female patient was admitted to our hospital with a 1-wk history of recurrent, right-sided abdominal pain, moderate in intensity, which lasted for many hours, and was associated with nausea but not vomiting. She had no change in bowel habits and was passing flatus and stools.

Her past medical history included hypertension for 10 years, dyslipidemia and diffuse diverticulosis with recurrent episodes of diverticulitis that necessitated left partial colectomy with primary anastomosis 4 years ago. As a result of disease progression, she underwent open total colectomy with an ileorectal anastomosis. She presented at 6 wk after surgery. Her medication history included valsartan, propranolol, fenofibrate, laxatives, antispasmodics and fibers. She had no known allergies, no significant family history, and a review of her systems was unremarkable.

Upon physical examination, the patient appeared well, in no acute distress and had stable vital signs. The remainder of the examination was unremarkable, except for moderate tenderness upon superficial and deep palpation of the abdomen (right quadrant, and a feeling of an ill-defined mass. Her laboratory profile was normal.

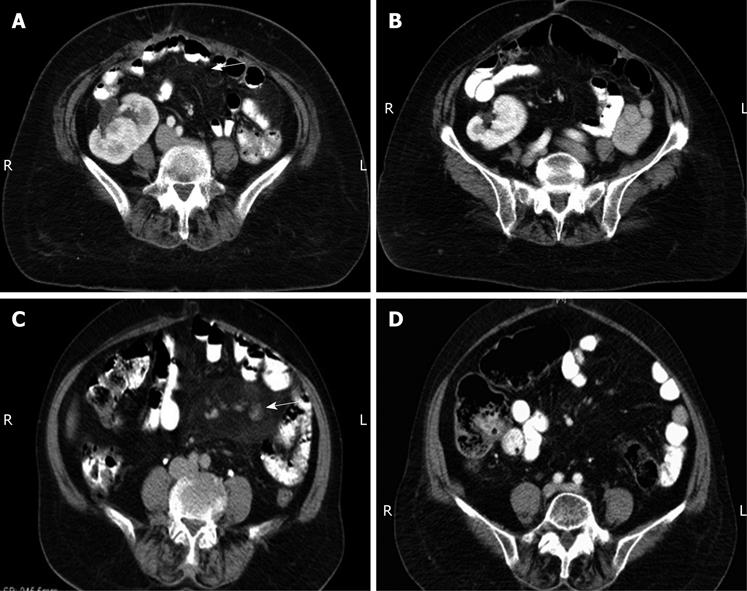

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen was performed using reconstructed slice thickness of 5 mm after oral and intravenous (iv) contrast administration, which showed a focal increase in density of the mesenteric fat with stranding in the supra-umbilical region, which was most probably inflammatory in origin and suggestive of mesenteric panniculitis (Figure 1A). This finding was surprising, especially in the light of a previous laparotomy a few weeks before, which revealed a clean abdomen.

The patient was started on prednisone 40 mg daily and was followed-up closely. Her symptoms gradually decreased in intensity and pain disappeared totally within 8 wk. Follow up CT 3 mo later showed a decrease in the mesenteric mass by 80%-90% (Figure 1B). However, she could not tolerate the steroids much longer because of peripheral neuropathy and hyperglycemia, therefore, she was switched to colchicine 100 mg daily orally.

Her status was reassessed 6 mo later, and CT showed persistence of the positive response and absence of the mass. Currently, she has been off treatment for 6 mo without recurrence of any symptoms.

A 74-year-old female patient presented to our care because of a chronic history of abdominal discomfort. Her symptoms were episodic and included discomfort that lasted a few minutes, which was associated with vomiting and followed by syncope of a few seconds duration. She had ho abdominal pain, no change in bowel habits or hematochezia and no weight loss.

Her past medical history was significant for hypertension, herniated vertebral disc, peptic ulcer disease and diverticulosis. At the time of presentation, the patient was taking perindopril, levothyroxine and risedronate. She had no known allergies to any medication or substance, and no significant family history. A review of her systems was notable for nausea and occasional vomiting.

Upon physical examination, she appeared well, in no acute distress and had stable vital signs. Laboratory data revealed a normal complete blood count, blood chemistry and coagulation profile. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed and showed mild non-erosive gastritis with a positive urease test for Helicobacter pylori.

Spiral CT of the abdomen and pelvis, using a reconstructed slice thickness of 5 mm after oral and iv contrast administration showed a hazy, veil-like hyper-attenuation of the mesenteric root and leaves, primarily seen in the jejunum. The radiological picture was highly suggestive of mesenteric panniculitis (Figure 1C). Interspersed subcentimetric mesenteric lymph nodes were also seen. The largest one was located in a lower jejunal mesenteric leaflet of the left lower quadrant, and reached 9 mm in the short axis. The rest of the examination was normal.

Treatment was started with 40 mg prednisone once daily and she was discharged home. She had an excellent response that was demonstrated in her follow-up CT scan 2 mo later. The previously described increased density of the peri-pancreatic and mesenteric fat caused by panniculitis was no longer present. The mesenteric fat showed normal density with no evidence of inflammation or retroperitoneal or mesenteric adenopathy.

At this time, she had no abdominal complaints. She was still taking the same dose of steroids. Three months later, she was readmitted with acute herpes zoster infection. Treatment had to be aborted and prednisone was slowly tapered until discontinuation, and no other treatment was initiated. She was followed-up closely with no recurrence of symptoms and persistent radiological remission, as shown by CT repeated at 2 mo after steroid discontinuation (Figure 1D).

Mesenteric panniculitis is a rare inflammatory condition that is characterized by chronic and nonspecific inflammation of the adipose tissue of the intestinal mesentery. So far, 130 cases have been reported in the literature under several names: retractile mesenteritis, sclerosing mesenteritis, liposclerotic mesenteritis, isolated lipodystrophy of the mesentery, mesenteric lipomatosis, and lipogranuloma of the mesentery, and mesenteric manifestations of Weber-Christian disease[45]. Most studies have indicated that the disease is more common in men, with a male/female ratio of 2-3:1, and several reports have indicated it to be more common in Caucasian men. Incidence increases with age, and pediatric cases are exceptional, probably because children have less mesenteric fat when compared to adults[6].

The pathogenic mechanism of mesenteric panniculitis seems to be a nonspecific response to a wide variety of stimuli. Although various causal factors have been identified, the precise etiology remains unknown. Emory et al[2] have reported a series in which 84% of patients had a history of abdominal trauma or surgery. Furthermore, the disease is related to other factors, such as mesenteric thrombosis, mesenteric arteriopathy, drugs, thermal or chemical injuries, vasculitis, avitaminosis, autoimmune disease, retained suture material, pancreatitis, bile or urine leakage, hypersensitivity reactions, and even bacterial infection[67]. Other factors, such as gallstones, coronary disease, cirrhosis, abdominal aortic aneurysm, peptic ulcer, or chylous ascitis, have also been linked to this disease[8]. More recent studies have shown a strong relationship between tobacco consumption and panniculitis[7].

Retractile mesenteritis has been associated with a number of malignant diseases such as lymphoma, lung cancer, melanoma, colon cancer, renal cell cancer, myeloma, gastric carcinoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Hodgkin’s disease, large cell lymphoma (giant-cell carcinoma), carcinoid tumor, and thoracic mesothelioma[2679–11].

In over 90% of cases, mesenteric panniculitis involves the small-bowel mesentery, although it may sometimes involve the sigmoid mesentery[10]. On rare occasions, it may involve the mesocolon, peripancreatic region, omentum, retroperitoneum or pelvis[12].

The mean clinical progression is usually 6 mo, ranging from 2 wk to 16 years. The disease is often asymptomatic. When present, clinical symptoms vary greatly, and may include anorexia, abdominal pain, abdominal fullness, nausea, pyrexia, and weight loss[11]. On occasions, the disease may also present with merely a single or multiple palpable masses. Exceptionally, rectal bleeding, jaundice, gastric outlet obstruction, and even acute abdomen have been reported[2912]. Such a wide variety of manifestations means that a large number of illnesses must be considered for differential diagnosis, therefore, careful assessment by the treating physician is strongly advised (Table 1).

| Lymphoma |

| Lymphosarcoma |

| Carcinoid tumors |

| Desmoid tumors |

| Infectious diseases (tuberculosis and histoplasmosis) |

| Amyloidosis |

| Peritoneal mesothelioma |

| Desmoplastic carcinoma metastases |

| Whipple’s disease |

| Chronic inflammation due to foreign body |

| Reaction to adjacent cancer or chronic abscess |

| Retroperitoneal sarcoma |

Histologically, the disease progresses in three stages[6]. The first stage is mesenteric lipodystrophy, in which a layer of foamy macrophages replaces mesenteric fat. Acute inflammatory signs are minimal or non-existent; the disease tends to be clinically asymptomatic and prognosis is good. In the second stage, termed mesenteric panniculitis, histology reveals an infiltrate made up of plasma cells and a few polymorphonuclear leukocytes, foreign-body giant cells, and foamy macrophages. Most common symptoms include fever, abdominal pain, and malaise. The final stage is retractile mesenteritis, which shows collagen deposition, fibrosis, and inflammation. Collagen deposition leads to scarring and retraction of the mesentery, which in turn, leads to the formation of abdominal masses and obstructive symptoms. The exact diagnosis is often difficult and is usually made by finding one of three major pathological features: fibrosis, chronic inflammation, or fatty infiltration of the mesentery. To some extent, all three components are present in most cases[13].

Blood tests tend to be within the normal range. Neutrophilia, increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate or anemia have been reported occasionally in the retractile mesenteritis stage[6].

Some reports even go as far as stating that few or none of the patients with mesenteric panniculitis can be diagnosed correctly before operation[414]. However, with the advent of imaging technology like high-resolution CT or magnetic resonance imaging, distinguishing mesenteric panniculitis from other mesenteric diseases with similar imaging features such as carcinomatosis, carcinoid tumor, lymphoma, desmoid tumor, and mesenteric edema seems possible and feasible[1516]. The imaging appearance of mesenteric panniculitis varies depending on the predominant tissue component (fat necrosis, inflammation, or fibrosis)[17]. It is visualized usually as a heterogeneous mass with a large fat component and interposed linear bands with soft tissue density in cases of mesenteric panniculitis, or as a homogeneous mass of soft tissue density in cases of retractile mesenteritis. Colonoscopy is usually unrevealing, since mesenteric panniculitis is extrinsic to the bowel. Paracentesis that reveals inflammatory cell populations without mitotic figures can also aid diagnosis.

Mesenteric panniculitis resolves spontaneously in most cases, however, palpable masses may often be found between 2 and 11 years after diagnosis, especially in patients with associated comorbidity[6]. In such cases, several types of treatment have been proposed but no consensus has been established. In general, treatment has been reserved for symptomatic cases. Incidental masses may be observed and left untreated. Therapy is individualized on a case by case basis. Treatment may be attempted with a variety of drugs including steroids, thalidomide, cyclophosphamide, progesterone, colchicine, azathioprine, tamoxifen, antibiotics and emetine, or radiotherapy, with different degrees of success[18–20]. Surgery may be attempted if medical therapy fails or in the presence of life-threatening complications such as bowel obstruction or perforation[5].

Our two cases showed different presentations: one was chronic and compatible with most published data, and the other was post-surgical, which makes it a very rare occurrence. Two different treatment regimens were used successfully in both cases. This should encourage us to review our approach to those cases that are always considered to be surgical, and leave room for medical treatment, which may be more effective than previously noted.

In conclusion, mesenteric panniculitis is a rare clinical entity that occurs independently or in association with other disorders. Diagnosis of this nonspecific, benign inflammatory disease is a challenge to gastroenterologists, radiologists, surgeons and pathologists. CT features of the disease, usually highly suggestive, have recently been delineated clearly. Open biopsy seems rarely necessary. There is no standardized treatment, and it may consist of anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive agents. We recommend resection only when the advanced inflammatory changes become irreversible or in cases of bowel obstruction. Overall prognosis is usually good and recurrence seems to be rare.

| 1. | Zissin R, Metser U, Hain D, Even-Sapir E. Mesenteric panniculitis in oncologic patients: PET-CT findings. Br J Radiol. 2006;79:37-43. |

| 2. | Emory TS, Monihan JM, Carr NJ, Sobin LH. Sclerosing mesenteritis, mesenteric panniculitis and mesenteric lipodystrophy: a single entity? Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:392-398. |

| 3. | Vettoretto N, Diana DR, Poiatti R, Matteucci A, Chioda C, Giovanetti M. Occasional finding of mesenteric lipodystrophy during laparoscopy: a difficult diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5394-5396. |

| 4. | Grieser C, Denecke T, Langrehr J, Hamm B, Hanninen EL. Sclerosing Mesenteritis as a Rare Cause of Upper Abdominal Pain and Digestive Disorders. Acta Radiol. 2008;13:1-3. |

| 5. | Gu GL, Wang SL, Wei XM, Ren L, Li DC, Zou FX. Sclerosing mesenteritis as a rare cause of abdominal pain and intraabdominal mass: a cases report and review of the literature. Cases J. 2008;1:242. |

| 6. | Delgado Plasencia L, Rodríguez Ballester L, López-Tomassetti Fernández EM, Hernández Morales A, Carrillo Pallarés A, Hernández Siverio N. [Mesenteric panniculitis: experience in our center]. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2007;99:291-297. |

| 7. | Daskalogiannaki M, Voloudaki A, Prassopoulos P, Magkanas E, Stefanaki K, Apostolaki E, Gourtsoyiannis N. CT evaluation of mesenteric panniculitis: prevalence and associated diseases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:427-431. |

| 8. | Patel N, Saleeb SF, Teplick SK. General case of the day. Mesenteric panniculitis with extensive inflammatory involvement of the peritoneum and intraperitoneal structures. Radiographics. 1999;19:1083-1085. |

| 10. | McCrystal DJ, O'Loughlin BS, Samaratunga H. Mesenteric panniculitis: a mimic of malignancy. Aust N Z J Surg. 1998;68:237-239. |

| 11. | Shah AN, You CH. Mesenteric lipodystrophy presenting as an acute abdomen. South Med J. 1982;75:1025-1026. |

| 12. | Akram S, Pardi DS, Schaffner JA, Smyrk TC. Sclerosing mesenteritis: clinical features, treatment, and outcome in ninety-two patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:589-596; quiz 523-524. |

| 13. | Seo M, Okada M, Okina S, Ohdera K, Nakashima R, Sakisaka S. Mesenteric panniculitis of the colon with obstruction of the inferior mesenteric vein: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:885-889. |

| 14. | Ege G, Akman H, Cakiroglu G. Mesenteric panniculitis associated with abdominal tuberculous lymphadenitis: a case report and review of the literature. Br J Radiol. 2002;75:378-380. |

| 15. | Pickhardt PJ, Bhalla S. Unusual nonneoplastic peritoneal and subperitoneal conditions: CT findings. Radiographics. 2005;25:719-730. |

| 16. | Horton KM, Lawler LP, Fishman EK. CT findings in sclerosing mesenteritis (panniculitis): spectrum of disease. Radiographics. 2003;23:1561-1567. |

| 17. | Koornstra JJ, van Olffen GH, van Noort G. Retractile mesenteritis: to treat or not to treat. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44:408-410. |

| 18. | Parra-Davila E, McKenney MG, Sleeman D, Hartmann R, Rao RK, McKenney K, Compton RP. Mesenteric panniculitis: case report and literature review. Am Surg. 1998;64:768-771. |

| 19. | Mazure R, Fernandez Marty P, Niveloni S, Pedreira S, Vazquez H, Smecuol E, Kogan Z, Boerr L, Mauriño E, Bai JC. Successful treatment of retractile mesenteritis with oral progesterone. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1313-1317. |