Published online Aug 7, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3660

Revised: June 19, 2009

Accepted: June 26, 2009

Published online: August 7, 2009

AIM: To evaluate the short- and long-term outcomes of bilateral liver resection for bilateral intrahepatic stones.

METHODS: We reviewed retrospectively 101 consecutive patients with bilateral intrahepatic stones who underwent bilateral liver resection in the past 10 years. The short- and long-term outcomes of the patients were analyzed. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to identify the risk factors related to stone recurrence.

RESULTS: There was no surgical mortality in this group of patients. The surgical morbidity was 28.7%. Stone clearance rate after hepatectomy was 84.2% and final clearance rate was 95.0% following postoperative choledochoscopic lithotripsy. The stone recurrence rate was 7.9% and the occurrence of postoperative cholangitis was 6.5% in a median follow-up period of 54 mo. The Cox proportional hazards model indicated that liver resection range, less than the range of stone distribution (P = 0.015, OR = 2.152) was an independent risk factor linked to stone recurrence.

CONCLUSION: Bilateral liver resection is safe and its short- and long-term outcomes are satisfactory for bilateral intrahepatic stones.

- Citation: Li SQ, Liang LJ, Hua YP, Peng BG, Chen D, Fu SJ. Bilateral liver resection for bilateral intrahepatic stones. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(29): 3660-3663

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i29/3660.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.3660

Intrahepatic stones is a common disease in Eastern Asia. Hepatectomy that can remove stones, strictured bile duct and atrophic liver tissue seems to be the optimal treatment for intrahepatic stones in selected patients. It has been accepted increasingly as the definitive treatment for intrahepatic stones in Eastern Asian[1–5] and some European countries[67]. Most of the previous studies have demonstrated that liver resection for intrahepatic stones has been confined to unilateral resection. The outcomes of bilateral liver resection for bilateral intrahepatic stones have not been clarified.

The aims of this study were to evaluate the short- and long-term outcomes of bilateral liver resection for bilateral intrahepatic stones.

The study included 101 consecutive patients with bilateral intrahepatic stones who underwent elected bilateral liver resection between January 1997 and December 2007. There were 45 men and 56 women with an average age of 47.2 years (range, 20-72 years). Forty-nine (48.6%) patients had undergone previous biliary surgery. Fifty-two (51.5%) patients also had extrahepatic stones. Twenty (19.8%) patients also had common bile duct cysts, and nine (8.9%) had hilar stricture.

The indications of hepatectomy for bilateral intrahepatic stones were: (1) bilateral segmental liver parenchymal atrophy caused by stones; (2) stricture of stone-bearing bile ducts; (3) estimated liver remnant is sufficient after hepatectomy; and (4) the general condition of patient was good and liver function was Child-Pugh A class, and he/she could tolerate the hepatectomy.

Preoperative preparation included liver biochemistry, coagulation profile, ultrasound and computed tomography (CT). If the liver resection range was larger than four liver segments, volumetric CT was done to estimate the volume of the liver remnant. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography was performed selectively for patients with intrahepatic bile duct dilatation, which aimed at delineating the site of the bile duct stricture. For patients with acute cholangitis, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiodrainage (PTCD) guided by ultrasound or endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) was performed preoperatively, and definitive hepatectomy was performed 1-3 mo later[8]. There were 17 patients with acute cholangitis who received PTCD and ENBD before definitive hepatectomy.

Bile leakage, defined as bile fluid draining from the peritoneal cavity or oozing from the wound, was demonstrated by cholangiography through a T tube or transanastomotic tube[8]. Postoperative liver failure was defined as serum total bilirubin > 85 &mgr;mol/L and coagulopathy (international normalized ratio > 1.5) that lasted for > 2 wk after hepatectomy. Patients presented with ascites and/or encephalopathy. Surgical mortality was defined as death within 30 d after hepatectomy. Major hepatectomy was defined as resection of more than three liver segments.

Patients after surgery were followed up twice a year. Liver biochemistry and ultrasound were performed routinely. If stone recurrence was highly suspected, CT was performed. Stone recurrence was defined as stone recurrence intra- or extrahepatically after complete initial clearance. Patients who presented with right upper quadrant pain, chill and fever, with or without jaundice, were considered to have an acute attack of cholangitis.

At the end of the study (December 2008), 92 of 101 patients completed a median follow-up period of 54 mo (12-120 mo).

Patient data were analyzed by SPSS version 13.0 software (Chicago, IL, USA). The Cox proportional hazards model was used to identify the risk factors associated with stone recurrence. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

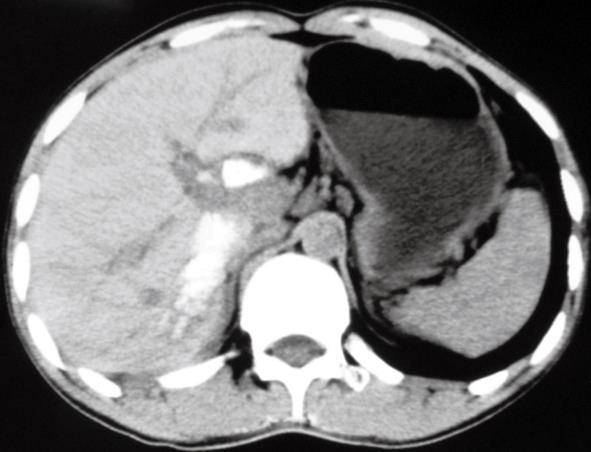

The detailed procedures of bilateral liver resection of the 101 patients are listed in Table 1. The most common procedure performed in this group of patients was left lateral sectionectomy plus right posterior sectionectomy (Figure 1), which accounted for 37.6% of patients. Four patients underwent more aggressive liver resection, which included two left trisegmentectomies; one left and right hepatectomy that left only the hypertrophic caudate lobe (970 g estimated by volumetric CT); and one segmentectomy of segments 2, 3, 4, 5, 7 and 8, which left only the hypertrophic segment 6 (670 g estimated by volumetric CT).

| Procedures | n (%) |

| Left lateral sectionectomy plus right posterior sectionectomy | 38 (37.6) |

| Left lateral sectionectomy plus segmentectomy of segments 5-7 | 18 (17.8) |

| Hemihepatectomy plus ipsilateral segmentectomy | 21 (20.8) |

| Left hepatectomy plus right posterior sectionectomy | 11 (10.9) |

| Left hepatectomy plus left caudate sectionectomy | 9 (9.0) |

| Left trisegmentectomy | 2 (2.0) |

| Left and right hepatectomy (leaving hypertrophic caudate lobe) | 1 (1.0) |

| Segmentectomy of segments 2-5, 7, 8 (leaving hypertrophic segment 6) | 1 (1.0) |

Twenty-nine of 101 (28.7%) patients had concomitant hepaticojejunostomy following resection of common bile duct cysts and bile duct strictureplasty.

The consistency between liver resection range and the range of stone distribution was classified into two categories: liver resection range equal to stone distribution, and liver resection range less than stone distribution. Fifty-eight of 101 (57.4%) patients had a liver resection range that was equal to the range of stone distribution, and the others had a resection range that was less than the range of stone distribution.

There was no surgical mortality in our group of patients. Twenty-nine (28.7%) patients developed one kind of complication (Table 2). One patient suffered from postoperative hemobilia at postoperative day 5, and he underwent emergency surgical exploration. Bleeding of the anastomotic mouth was found and hemostasis was achieved by fine suturing the bleeding vessel at operation. He recovered well. The other complications were cured by conservative treatment.

| Complications | n (%) |

| Wound infection | 18 (17.8) |

| Bile leak | 8 (8.0) |

| Peritoneal infection | 7 (7.0) |

| Pleural effusion | 10 (10.0) |

| Liver failure | 2 (2.0) |

| Pulmonary infection | 2 (2.0) |

| Hemobilia | 1 (2.0) |

| Sepsis | 1 (1.0) |

Residual stone was confirmed by postoperative cholangiography through a T tube and transanastomotic tube, or ultrasound findings. Sixteen patients had residual stones after hepatectomy. The stone clearance rate was 84.2% (85/101). The final stone clearance rate was 95.0% (95/101) following 1-5 sessions of postoperative choledochoscopic lithotripsy through the T-tube or transanastomotic tube route. Residual stones could not be completely removed in five patients. This was because of tiny stones located at the peripheral bile duct or segregated bile duct that could not be reached by choledochoscopy (n = 3), or because the sharp angle formation of the jejunal loop of hepaticojejunostomy hindered entry of the choledochoscope (n = 2).

At the end of this study, 92 patients had completed the follow-up, including 89 whose stones were completely removed at initial operation and three patients with residual stones. In a median follow-up period of 54 mo, seven (7.9%) patients developed stone recurrence. Six patients suffered from at least one attack of acute cholangitis. Four of six patients had stone recurrence and the other two had residual stones. The occurrence of acute cholangitis was 6.5% (6/92). Stone recurrence and residual stones were the major causes of postoperative acute cholangitis.

To identify the risk factors related to stone recurrence, six clinical factors including age (≥ 50, < 50 years), sex, previous history of biliary surgery, complicated with extrahepatic stones, concomitant hepaticojejunostomy, and consistency between liver resection range and the range of stone distribution were analyzed by the Cox proportional hazards model. It indicated that liver resection range less than the range of stone distribution (P = 0.015, OR = 2.152, 95% CI: 1.624-4.721) was the only independent risk factor associated with stone recurrence.

The treatment principle of intrahepatic stones consists of complete removal of the stones, strictured bile duct and atrophic liver parenchyma, and establishment of satisfactory biliary drainage. Bilateral intrahepatic stones is a complex condition, and treatment of this disease remains a challenge. Hepatectomy that can remove stones and resect strictured bile ducts seems to be the optimal treatment for intrahepatic stones. Whether bilateral liver resection is feasible for bilateral intrahepatic stones and its outcome have not been evaluated.

Our results demonstrated that stone clearance rate after hepatectomy was 84.2%, and the final clearance rate was 95% following choledochoscopic lithotripsy. There was no surgical mortality. The stone recurrence rate was 7.9% and the occurrence of acute cholangitis episodes was 6.5%, after a median follow-up period of 54 mo. This indicated that bilateral liver resection for bilateral intrahepatic stones was safe, and its short- and long-term outcomes were satisfactory.

The locations of intrahepatic stones are strictly within segments. Most commonly, the involved segments are destroyed and atrophic, and the stone-bearing bile ducts show fibrotic thickening or stricture because of repeated attacks of acute cholangitis, whereas, the non-involved segments are hypertrophic (especially in patients with bilateral stones). Therefore, anatomical hepatectomy for the affected segments is feasible, with the prerequisite of there being sufficient remnant liver. The Cox proportional hazards model indicated that a liver resection range less than the range of stone distribution was the only independent risk factor associated with stone recurrence in this study. A liver resection range less than the range of stone distribution may leave bile duct stricture, which is a key predisposing factor for stone recurrence[9–11].

There is reluctance among some surgeons to perform bilateral liver resection for bilobar stones because of the associated surgical risks. It has been reported that hepatectomy for the more severely affected side, combined with hepaticojejunostomy for removal of stones on the other side, is an effective approach[2]. We do not advocate that the liver resection range should be consistent with the range of stone distribution for every patient with bilateral intrahepatic stones. However, we suggest strongly that the strictured stone-bearing bile ducts and atrophic liver tissue should be resected, with the prerequisite of leaving sufficient remnant liver. This is because the strictured inflammatory bile ducts and atrophic tissue are predisposing risk factors for stone recurrence[910] and the occurrence of cholangiocarcinoma[12–14]. If the estimated future liver remnant was not sufficient, hepatectomy was performed for the severely affected side and the ipsilateral stones were removed as cleanly as possible via intraoperative choledochoscopic lithotripsy. Whenever possible, we do not perform hepaticojejunostomy for intrahepatic stones, but attempt to preserve the normal anatomy of the common bile duct because hepaticojejunostomy cannot drain residual stones effectively[15], and it has a high incidence of cholangitis after hepaticojejunostomy[1617]. Twenty-nine patients in our group had concomitant hepaticojejunotomy following resection of common bile duct cysts and bile duct strictureplasty.

All liver resections in our 101 patients were major hepatectomies (resection of more than three segments). There was no surgical mortality and the postoperative morbidity was 28.7%. We concluded that the zero surgical mortality and acceptable morbidity of this study were the result of deliberate preoperative preparations. Preoperative volumetric CT estimation is of critical importance for patients who undergo resection of more than four liver segments. Sufficient future remnant liver is mandatory for preventing postoperative liver failure. For patients with acute cholangitis, preoperative PTCD or ENBD is indicated for relieving biliary sepsis. Definitive hepatectomy is performed 1 mo later after sepsis subsides[8]. This management may decrease the surgical morbidity.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that bilateral liver resection is safe and its short- and long-term outcomes are satisfactory. A liver resection range less than the range of stone distribution is an independent risk factor associated with stone recurrence. Complete resection of strictured stone-bearing bile ducts and atrophic liver tissue, with the prerequisite of sufficient future remnant liver may decrease stone recurrence.

Intrahepatic stones is a common disease in Eastern Asia. Hepatectomy that can remove stones, strictured bile duct and atrophic liver tissue seems to be the optimal treatment for intrahepatic stones, and has been accepted increasingly as the definitive treatment. Most of the previous studies have demonstrated that liver resection for intrahepatic stones is confined to unilateral resection. The outcomes of bilateral liver resection for bilateral intrahepatic stones have not been clarified. Therefore, this study was conducted to evaluate the short- and long-term outcomes of bilateral liver resection for bilateral intrahepatic stones.

This study evaluated the feasibility and outcomes of bilateral liver resection for bilateral intrahepatic stones.

There have been an increasing number of studies on hepatectomy for intrahepatic stones in recent years. For the subgroup of patients with bilateral intrahepatic stones, the feasibility and outcome of bilateral liver resection have not been clarified. This study is believed to be the first to demonstrate that bilateral liver resection for bilateral intrahepatic stones is safe and its long-term outcome is satisfactory, with a stone recurrence rate of 7.9% and an acute cholangitis rate of 6.5%.

The most important clinical application of this study is that bilateral liver resection is indicated in a subgroup of patients with bilateral intrahepatic stones. The results of this study expand the surgical indications of hepatectomy for intrahepatic stones.

Bilateral liver resection is defined as bilateral resection of stone-bearing segments, with the prerequisite of leaving a sufficient liver remnant, for example, left lateral sectionectomy plus right posterior sectionectomy.

This paper is very interesting and well written. The study is provocative and the findings might be helpful for understanding the indications for bilateral liver resection of bilateral intrahepatic stones.

| 1. | Uchiyama K, Onishi H, Tani M, Kinoshita H, Ueno M, Yamaue H. Indication and procedure for treatment of hepatolithiasis. Arch Surg. 2002;137:149-153. |

| 2. | Chen DW, Tung-Ping Poon R, Liu CL, Fan ST, Wong J. Immediate and long-term outcomes of hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis. Surgery. 2004;135:386-393. |

| 4. | Lee TY, Chen YL, Chang HC, Chan CP, Kuo SJ. Outcomes of hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis. World J Surg. 2007;31:479-482. |

| 5. | Kim BW, Wang HJ, Kim WH, Kim MW. Favorable outcomes of hilar duct oriented hepatic resection for high grade Tsunoda type hepatolithiasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:431-436. |

| 6. | Catena M, Aldrighetti L, Finazzi R, Arzu G, Arru M, Pulitanò C, Ferla G. Treatment of non-endemic hepatolithiasis in a Western country. The role of hepatic resection. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88:383-389. |

| 7. | Al-Sukhni W, Gallinger S, Pratzer A, Wei A, Ho CS, Kortan P, Taylor BR, Grant DR, McGilvray I, Cattral MS. Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis with hepatolithiasis--the role of surgical therapy in North America. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:496-503. |

| 8. | Li SQ, Liang LJ, Peng BG, Lu MD, Lai JM, Li DM. Bile leakage after hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis: risk factors and management. Surgery. 2007;141:340-345. |

| 9. | Huang MH, Chen CH, Yang JC, Yang CC, Yeh YH, Chou DA, Mo LR, Yueh SK, Nien CK. Long-term outcome of percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopic lithotomy for hepatolithiasis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2655-2662. |

| 10. | Chen C, Huang M, Yang J, Yang C, Yeh Y, Wu H, Chou D, Yueh S, Nien C. Reappraisal of percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopic lithotomy for primary hepatolithiasis. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:505-509. |

| 11. | Jeng KS, Yang FS, Chiang HJ, Ohta I. Bile duct stents in the management of hepatolithiasis with long-segment intrahepatic biliary strictures. Br J Surg. 1992;79:663-666. |

| 12. | Kuroki T, Tajima Y, Kanematsu T. Hepatolithiasis and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: carcinogenesis based on molecular mechanisms. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2005;12:463-466. |

| 13. | Lee CC, Wu CY, Chen GH. What is the impact of coexistence of hepatolithiasis on cholangiocarcinoma? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:1015-1020. |

| 14. | Zhou YM, Yin ZF, Yang JM, Li B, Shao WY, Xu F, Wang YL, Li DQ. Risk factors for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a case-control study in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:632-635. |

| 15. | Li SQ, Liang LJ, Peng BG, Lai JM, Lu MD, Li DM. Hepaticojejunostomy for hepatolithiasis: a critical appraisal. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4170-4174. |