CASE REPORT

An 81 year-old Caucasian man presented to the emergency department with the chief complaint of continuous rectal bleeding of several months duration, which was particularly associated with bowel movements. He reported chronic intermittently bleeding hemorrhoids for about 20 years. He denied comorbid conditions and took no medications. He also denied recent weight loss, change in appetite or bowel habits. This patient reportedly underwent a colonoscopic evaluation about four years prior to the current presentation, with negative results. His family history was unremarkable for gastrointestinal benign or malignant problems. Physical examination revealed a gentleman who appeared younger than the stated age, in no acute distress. Perianal visual and digital examination showed a blood-covered 3 cm × 4 cm pedunculated mass protruding from the anus by a stalk. Significant laboratory data demonstrated microcytic anemia (hemoglobin of 6.4 mg/dL) and normal coagulation times. He was transfused with packed red blood cells and the lesion was amputated at the bedside. Microscopic analysis revealed an infiltrating well-differentiated adenocarcinoma arising from a villous adenoma (Figure 1). Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen and pelvis demonstrated no evidence of metastatic disease. The patient was subsequently taken to the operating room for examination under anesthesia and complete excision of the anal mass. Intraoperative findings revealed very large hemorrhoids, of 0.5 cm in diameter on average occupying the entire circumference of the anus (Figure 2). Gentle dilation of the anus revealed an ulcerated area of 2 cm in length at 5 o’clock in the supine position extending from the anal orifice to about 1 cm into the anal canal. Hemorrhoidectomy was performed and the ulcerated tissue was excised. Microscopic evaluation showed evidence of the prior procedure, but did not show residual neoplasm. This tumor was staged as T1N0M0.

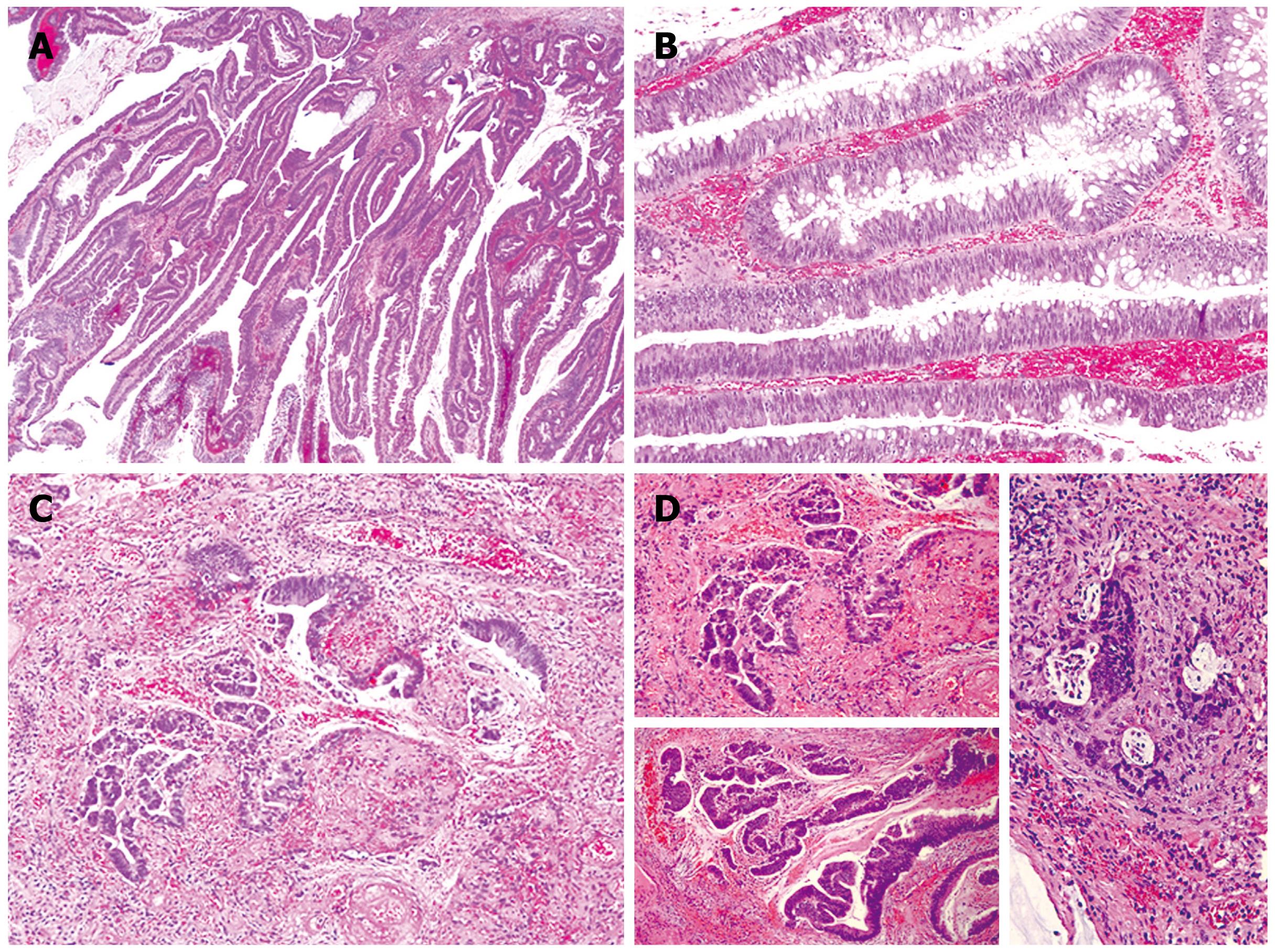

Figure 1 Microscopic sections.

A: The adenoma demonstrate villous architecture with long, delicate fronds (HE, × 40); B: The villous fronds are lined by dysplastic, intestinal-type epithelium with frequent goblet cells (HE, × 100); C and D: Multiple foci of invasive carcinoma are identified, with invasion confined to the lamina propria (HE, × 100).

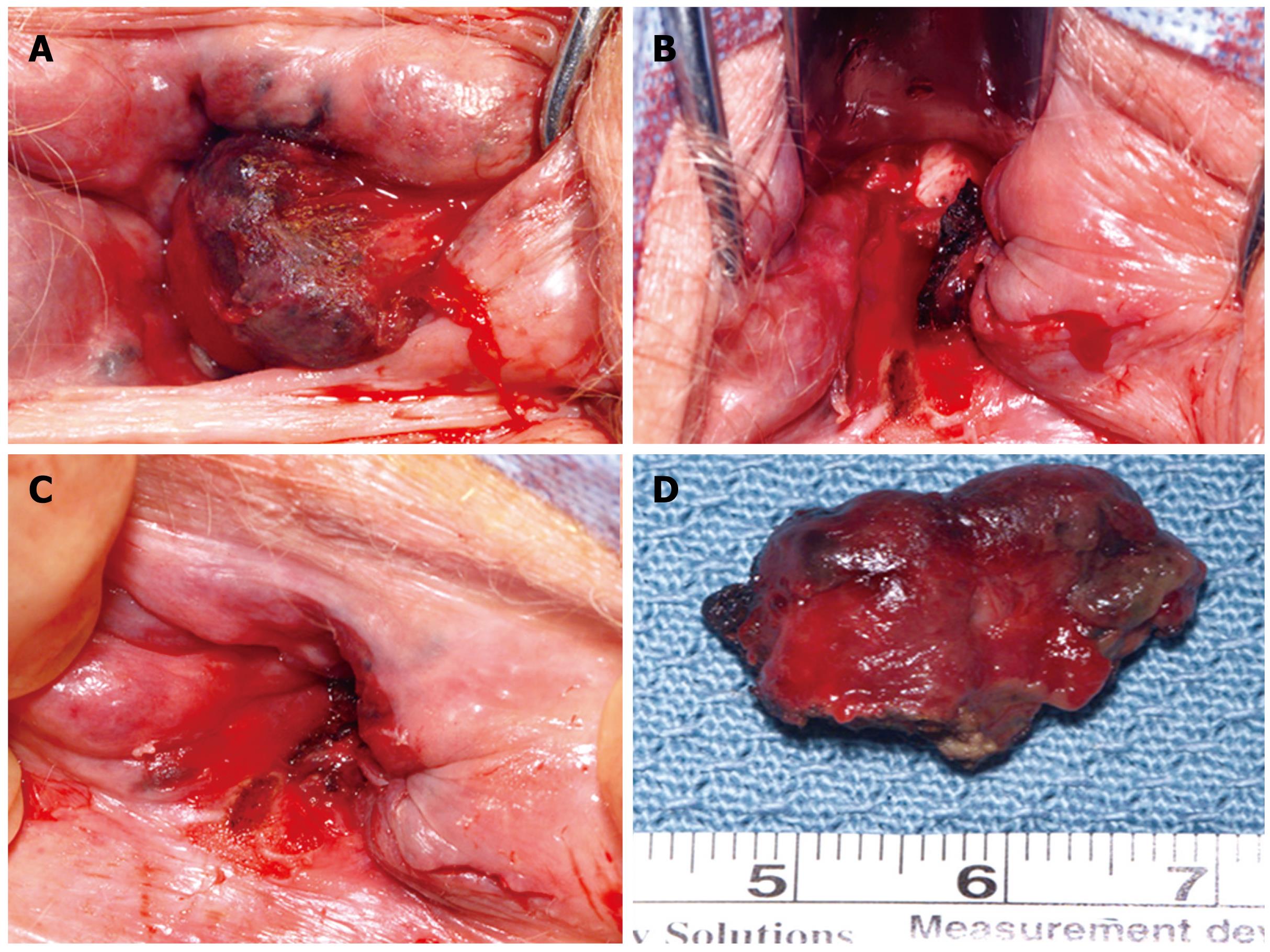

Figure 2 Intraoperative photographs.

A and D: Very large hemorrhoids up to 2 cm circumferentially located around the anal canal; B: The final appearance after complete excision of the hemorrhoids and the malignant mass; C: The area that contained the adenocarcinoma, previously excised in the emergency department, and prior to operating room excision.

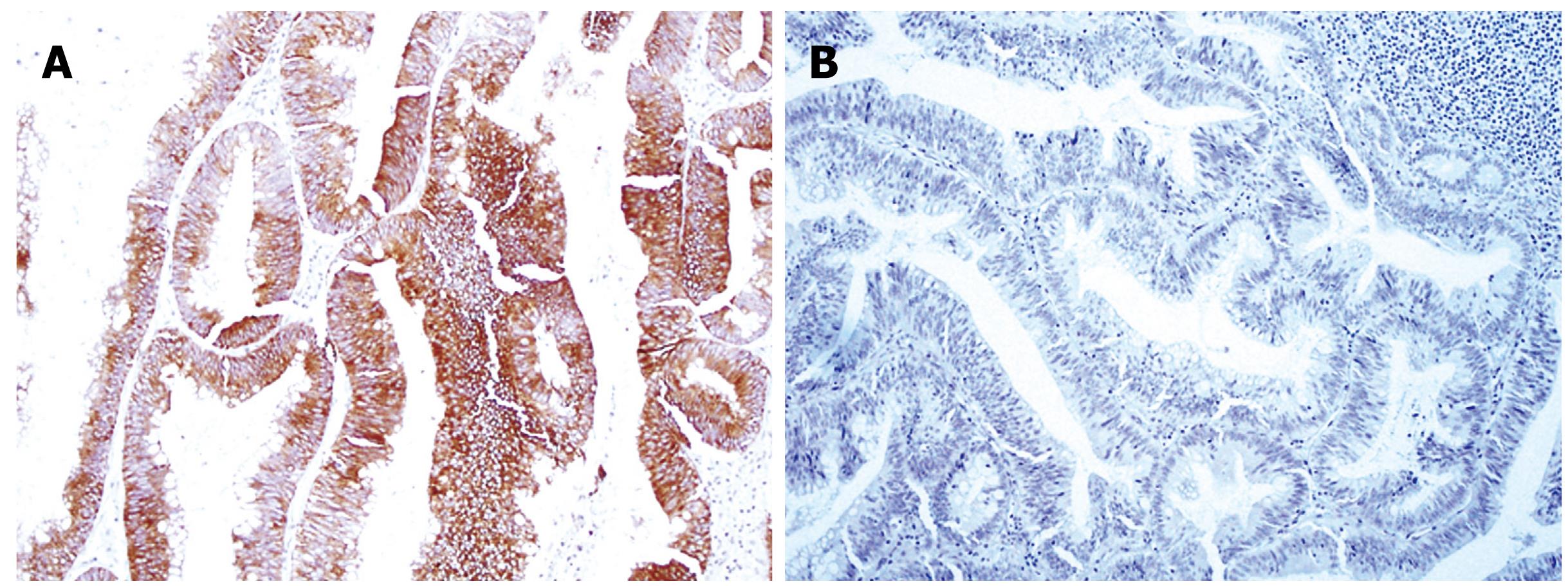

Detailed microscopic evaluation of the mass showed villous fronds, lined by dysplastic, intestinal-type epithelium with scattered goblet cells. Several microscopic foci of invasion into the lamina propria were identified. The neoplasm demonstrated diffuse staining for cytokeratin (CK)-20 and was negative for CK7 (Figure 3). Histologic examination of the residual anal tissue excised in the operating room clearly showed reactive (not malignant) rectal-type glands present near the surface, in between areas of squamous epithelium, as well as ulceration of superficial mucosa, consistent with the prior excision. No residual adenoma or carcinoma was identified.

Figure 3 Immunohistochemical staining.

A: Cytokeratin 20 is diffusely positive within the epithelium (× 100); B: Cytokeratin 7 is negative (× 100).

This case was discussed at our local tumor board conference. No consideration for further surgical or medical therapy was deemed appropriate for his optimal care. The patient was contacted two years after his intervention, and he is doing well, without recurrence of rectal bleeding or any other problems related to the tumor herein presented.

DISCUSSION

Primary anal cancer is a rare occurrence. However, its incidence has been rising over the last 25 years. Moreover, despite the small number of patients affected by these malignancies, they remain as one of the most challenging cancers to treat. Once thought to be related to chronic irritation, multiple risk factors, including human papillomavirus or human immunodeficiency virus infection, anal sexual intercourse, smoking and immunosuppression, have relatively recently been identified[1]. Anal tumors represent 5% of anorectal cancers. They have been classified in tumors of the anal canal and those of the anal margin, with mainly two histological types described. Among them, squamous carcinoma comprises approximately 95% of anal tumors[2].

Anal adenocarcinomas constitute about 5% of malignant anal neoplasms[2]. The latter tumors have been described in correlation with anal fistulae[3], hemorrhoids[4], after restorative proctocolectomy with a stapled ileal pouch-anal anastomosis without mucosectomy due to ulcerative colitis[56], or with Crohn’s disease[7]. Together, they account for 0.1% of all gastrointestinal cancers[8].

The progression of the normal colorectal epithelium to malignancy has been extensively studied in both experimental and clinical models, and a defined normal mucosa-adenoma-carcinoma sequence has been well recognized[9–11]. However, in the anal canal this information is lacking. Benign anal adenomas are extremely rare diagnoses. Multiple adenomatous polyps arising in the transitional zone of the anus in a patient with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) seven years after colon resection and ileo-anal anastomosis were described by Malassagne and colleagues[12]. Anand et al[13] reported a tubulo-villous adenoma which arose from either an anal gland or its duct that opens into the anus. These tumors are rarely encountered in patients without predisposing risk factors, such as FAP, ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease[13]. The above-mentioned transformation from normal epithelium to malignant tumors in the anal canal has only been previously recognized twice to the best of our knowledge. MacNeill and colleagues[14] described the case of an invasive apocrine adenocarcinoma arising in a benign adenoma in the perianal region of a 45-year-old woman. Obaidat et al[15] reported the occurrence of anal adenocarcinoma in situ associated with a tubulopapillary apocrine hidradenoma. These reports suggest that adenomatous elements from the squamocolumnar junction may demonstrate hyperplastic or malignant transformation in patients without genetic predisposition. Intraoperative examination in our case made us believe that an adenomatous polypoid lesion originated from distal anal tissue in an area of chronic inflammation and ulceration consistent with the anal transition zone. Some investigators, however, have found evidence to support alternative pathways to the adenoma-carcinoma sequence[16]. Specific mutations in key onco-suppressor genes have been found to relate to the anatomical site of the tumor and therefore, a significant proportion of rectal cancers may arise via alternative pathways to the Vogelstein model. Polyp behavior along with malignant propensity may actually be site dependent. Rectal polyps are thought to harbor a more aggressive phenotype. In the anal area, this remains uncertain.

CK-20 positivity with negative CK7 staining is an immunohistochemistry profile most consistent with rectal-type mucosa and is not in keeping with the apocrine or colloid types of adenocarcinoma that have been typically described as arising from the anal canal. In addition, the histologic appearance in this case of a well-formed villous adenoma with microscopic invasive carcinoma is different from typical anal gland carcinoma, which is characterized by small, tubular structures diffusely invading stroma. Clinical and pathologic findings in our case point to a true anal location for this pedunculated mass. Visual inspection showed this mass to arise distal to the dentate line, whereas histologic examination of the final excision specimen showed rectal-type glands present in between areas of normal squamous epithelium. The combination of these findings suggest the development of a tubulo-villous adenoma from rectal-type glands present in the anal mucosa, possibly as part of a reactive metaplastic phenomenon, similar to what was described in the case report from Anand and colleagues[13]. However, these authors did not report malignancy or immunohistochemistry findings. Therefore, whether the histologic profile of their case and ours is the same is unknown.

For anal adenocarcinoma, aggressive surgical resection remains the mainstay of therapy, with radiation therapy and chemotherapy used to aid in local disease control and for treatment of metastatic disease. A high rate of distant failure in this disease is responsible for the poor long-term prognosis[17]. Once invasive adenocarcinoma features were identified on pathologic examination of the polyp excised in the emergency department, this patient was taken to the operating room to ensure adequacy of resection. Some may argue that, to increase the chance of survival in this octogenarian, a larger extent of resection is needed. An analysis of 13 patients with primary anal adenocarcinoma who were treated over a 12-year period was performed[18]. With a median follow-up of 19 mo, the median survival was 26 mo, local failure rate was 37%, and the two-year actuarial survival was 62%. This study, although small, suggested that the combination of abdomino-perineal resection and combined modality therapy was a reasonable approach for this rare tumor[18]. However, this treatment strategy has to be individualized to both the patient and the tumor characteristics, as well as to the patients’ wishes.

The need to perform lower gastrointestinal endoscopy in patients at low risk for colorectal malignancies is debatable. Patients such as the one presented herein, had rectal bleeding as the presenting symptom and without other alarming signs for colorectal cancer, such as recently altered bowel habit, weight loss and family or personal history of colorectal neoplasms, which were studied with colonoscopy by Sotoudehmanesh et al[19]. A number of unexpected findings were identified, such as adenomatous polyps (3%), ulcerative colitis (6%) and Crohn’s disease (0.7%). Fissures were posterior in 106 cases (79.1%) and anterior in 27 cases (20.1%); one patient (0.7%) had both anterior and posterior fissures. The lower gastrointestinal endoscopy was abnormal in 10.4% of patients. No cases of adenocarcinoma were identified. Therefore, lower gastrointestinal endoscopy might be appropriate in this selected group of patients, if these findings are confirmed by further studies[19]. Carlo et al[20] specifically studied patients with hematochezia but without risk factors for neoplasia, and concluded that those patients younger than 45 years of age do not need a total colonoscopy, whereas they recommended mandatory total colonoscopy in older patients even in the presence of anal pathology. In the latter group they were able to identify proximal colonic inflammatory bowel disease, neoplastic polyps and even carcinoma.

In conclusion, the transition between normal tissue-adenoma-carcinoma has been well studied in the colorectal arena but very infrequently reported in the anal canal. Our report supports the application of the same concept for the anal region, at least for patients without major risk factors for the development of gastrointestinal malignancies. The infrequent occurrence of anal adenocarcinoma and the paucity of reports in the literature documenting these tumors make conclusions about this subject difficult to reach. The literature seems to suggest further endoscopic studies of the rest of the gastrointestinal tract in elderly patients with rectal bleeding and no risk factors for colorectal cancer.