Published online Jul 21, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3445

Revised: May 19, 2009

Accepted: May 26, 2009

Published online: July 21, 2009

A 52-year-old man had bloody stools during chemotherapy for gastric cancer. A colonoscopy revealed necrotizing ulcer-like changes. A biopsy confirmed the presence of amoebic trophozoites. Subsequently, peritonitis with intestinal perforation developed, and emergency peritoneal lavage and colostomy were performed. After surgery, endotoxin adsorption therapy was performed and metronidazole was given. Symptoms of peritonitis and colonitis resolved. However, the patient’s general condition worsened with the progression of gastric cancer. The patient died 50 d after surgery. Fulminant amoebic colitis is very rarely associated with chemotherapy. Amoebic colitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients who have bloody stools during chemotherapy.

- Citation: Hanaoka N, Higuchi K, Tanabe S, Sasaki T, Ishido K, Ae T, Koizumi W, Saigenji K. Fulminant amoebic colitis during chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(27): 3445-3447

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i27/3445.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.3445

Amoebic colitis, the disease caused by the intestinal protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica, is common and sometimes fatal[1]. The manifestations of intestinal amoebiasis vary from no symptoms to severe ulceration with perforation and peritonitis. There are many reports on fulminant amoebic colitis[23], but the development of fulminant amoebic colitis during chemotherapy is very rare. We describe our experience with a patient in whom fulminant amoebic colitis occurred while receiving chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer.

A 52-year-old man presented at our hospital suffering from epigastric pain. An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed advanced gastric cancer. Abdominal ultrasonography and computed tomography showed liver metastasis and intra-abdominal lymph-node metastasis. Unresectable advanced gastric cancer was diagnosed. Chemotherapy with oral S-1 (120 mg/d), given for four weeks followed by two weeks of rest[4], was started at the outpatient clinic. Computed tomography after seven courses of treatment showed disease progression. The chemotherapy regimen was therefore switched to second-line treatment with paclitaxel (140 mg/m2), given once every two weeks[5]. After six courses of the second-line treatment, constipation and diarrhea occurred repeatedly. During the seventh course of treatment, melena developed. Gastrointestinal bleeding caused by chemotherapy was suspected, and a gastrointestinal series was performed. An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed no bleeding from the primary tumor. Colonoscopic examination disclosed multiple hemorrhagic erosions throughout the colon. A biopsy of the same site revealed only inflammatory-cell infiltration. Subsequently, melena became more frequent, and symptoms worsened. The patient was admitted to the hospital for further evaluation and treatment. On admission, his body temperature was 38.1°C. The palpebral conjunctivae were anemic. There was a palpable mass in the epigastric region, associated with tenderness. Edema of the lower extremities was present. On admission, laboratory examinations showed anemia, hypoalbuminemia, and elevated transaminases. A culture specimen was negative for human immunodeficiency virus.

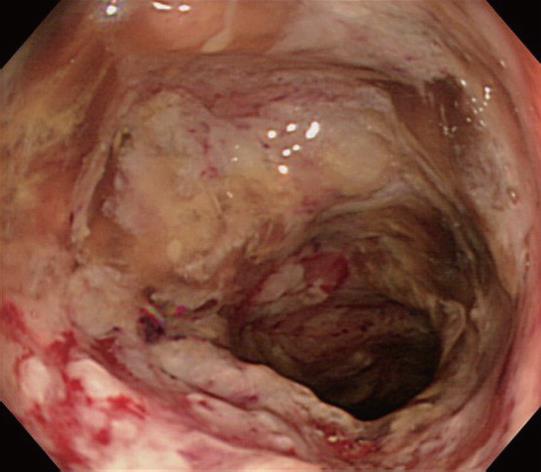

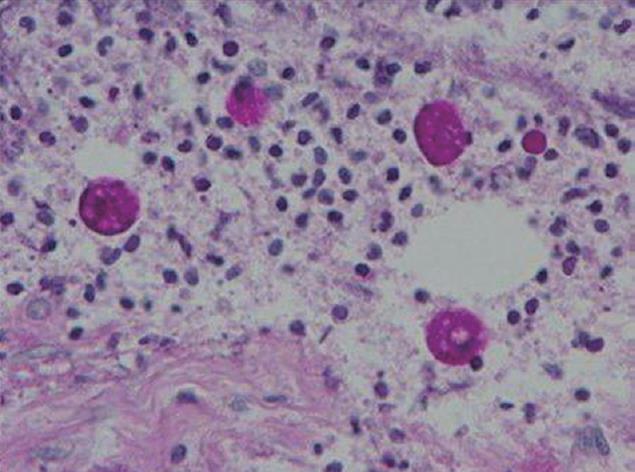

After admission, the colonoscopy was repeated. Necrotizing ulcer-like changes covered with slough were circumferentially seen from the rectum to the transverse colon (Figure 1). A biopsy of this region showed amoebic trophozoites (Figure 2). Signs of peritoneal irritation developed two days after colonoscopic examination. Intestinal perforation was diagnosed on computed tomography, and emergency surgery was performed. The perforation point was detected in the middle of the transverse colon. Peritoneal lavage and colostomy were performed. After surgery, endotoxin adsorption therapy was performed, and metronidazole was given. The symptoms of peritonitis and colonitis resolved. However, the patient’s general condition worsened due to progression of gastric cancer and the patient died 50 d after surgery.

Dysenteric amoebiasis is caused by protozoan parasites, which can be classified into two types: pathogenic E. histolytica and non-pathogenic Entamoeba dispar[1]. The ingestion of food and drink contaminated by pathogenic E. histolytica causes amoebiasis. About 90% of infections are asymptomatic, and the remaining 10% of infections produce a spectrum of clinical syndromes, ranging from dysentery to abscesses of the liver or other organs. It is reported that bowel perforation occurs in nearly 1% of the patients hospitalized for amoebiasis[6]; delayed diagnosis might have resulted in high mortality even after surgical therapy. Mortality for patients who undergo colectomy with proximal ileostomy and distal colostomy is 32% to 76%[23]. In this case, the perforation was pin hole-like lesion in the middle of transverse colon where friable mucosa and necrotizing ulcers were seen, suggesting that the reason for perforation was due to a discrete ulcer rather than due to the colonoscopic examination. However, the colectomy had not been performed and could not be reviewed pathologically, indicating limitations to diagnostic imaging studies. The possibility of iatrogenic perforation thus cannot be ruled out completely.

It is known that 4%-10% of asymptomatic individuals infected with E. histolytica develop disease over a year[1]. The onset is often gradual, but several studies have reported that steroids, the presence of diabetes mellitus, chronic alcoholism, and pregnancy can trigger fulminant amoebic colitis[17]. The classic endoscope findings of amoebic colitis are described as discrete, round ulcerations that range in size and are covered with white or yellow exudates[8]. However, amoebic colitis can be mistaken for other causes of necrotizing colitis, such as idiopathic inflammatory bowel diseases and pseudomembranous colitis of C. difficile, because the appearance of amoebic ulcers is variable on endoscopic examination. Oral metronidazole is generally used to treat amoebic colitis. However, complications occur when adequate therapy and appropriate antibiotics are not initiated at an early stage, all the more so in an immunosuppressed state. It is well known that there are two high risk groups in nonendemic areas; one is homosexual men, and the other is travelers from the tropics. As for the route and time of infection, the patient had been to Southeast Asia more than 20 years before disease onset; therefore, the possibility of an acquired oral infection cannot be ruled out. In Japan, dysenteric amoebiasis is most commonly caused by E. histolytica infection[9], with a particularly high incidence among homosexuals. However, it is noteworthy that our patient was not homosexual and that colitis developed during chemotherapy. In our patient, cytotoxic drugs are considered a risk factor of invasive amoebiasis, contributing to the immunosuppressed status. Cytotoxic drugs inhibit normal bacterial flora, suppress host defenses, and depress host immunity. In experimental free-living amoebic infections, some drugs suppressed host defenses with an increase in the mortality of infected mice[10].

Amoebic colitis should therefore be included in the differential diagnosis in immunosuppressed patients with gastrointestinal signs and symptoms, such as bloody stools.

| 2. | Takahashi T, Gamboa-Dominguez A, Gomez-Mendez TJ, Remes JM, Rembis V, Martinez-Gonzalez D, Gutierrez-Saldivar J, Morales JC, Granados J, Sierra-Madero J. Fulminant amebic colitis: analysis of 55 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:1362-1367. |

| 3. | Aristizábal H, Acevedo J, Botero M. Fulminant amebic colitis. World J Surg. 1991;15:216-221. |

| 4. | Koizumi W, Kurihara M, Nakano S, Hasegawa K. Phase II study of S-1, a novel oral derivative of 5-fluorouracil, in advanced gastric cancer. For the S-1 Cooperative Gastric Cancer Study Group. Oncology. 2000;58:191-197. |

| 5. | Koizumi W, Tanabe S, Higuchi K, Sasaki T, Nakayama S, Nakatani K, Nishimura K, Shimoda T, Azuma M, Ishido K. Optimal dose-finding study of bi-weekly paclitaxel in unresectable advanced or recurrent gastric cancer. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:3797-3802. |

| 6. | Barker EM. Colonic perforations in amoebiasis. S Afr Med J. 1958;32:634-638. |

| 8. | Juniper K. Amoebiasis. Clin Gastroenterol. 1978;7:3-29. |

| 9. | Martinez AJ. Acanthamoebiasis and immunosuppression. Case report. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1982;41:548-557. |

| 10. | Ohnishi K, Kato Y, Imamura A, Fukayama M, Tsunoda T, Sakaue Y, Sakamoto M, Sagara H. Present characteristics of symptomatic Entamoeba histolytica infection in the big cities of Japan. Epidemiol Infect. 2004;132:57-60. |