INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is one of the most lethal human malignancies. It ranks as the fourth most common cancer-related mortality in the Western world and fifth most common worldwide[1]. There were 37 680 new cases of pancreatic cancer and 34 290 deaths due to this disease in 2008 in the Unites States alone[2]. The overall 5-year survival rate of pancreatic cancer is estimated to be around 1%-4%, which is attributed to its aggressive growth behavior, such as early local spread and metastasis, and resistance to radiation and most systemic chemotherapies[1]. The poor prognosis is also due to the lack of effective early diagnosis. Consequently, most patients have been diagnosed with late stage disease. Currently, surgery remains the cornerstone of treatment. After resection, the 5-year survival rate is 10%-29%[3–5], but only 10%-15% of pancreatic cancer patients are suitable candidates for resection. For the non-operable pancreatic cancer cases, the most frequently used treatment methods include radiation and chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin or gemcitabine[6–8], or a combination of these modalities[9–11]. Growing evidence supports neoadjuvant therapy to downstage some pancreatic cancer patients from borderline resectable to resectable disease[1213], but its impact on long-term survival still needs further examination[14]. With this bleak background, there is an urgent need to develop novel treatments for pancreatic cancer.

SOURCES AND METABOLISM OF VITAMIN D

The production of vitamin D3 depends on solar ultraviolet B radiation (wavelength between 290-315 nm), which converts 7-dehydrocholesterol stored in the skin to previtamin D3. Previtamin D3 is then thermoisomerized to vitamin D3, which then enters the bloodstream and is bound to the vitamin D binding protein. Very little food naturally contains vitamin D. The cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D3 is normally responsible for over 90% of our vitamin D requirement[15]. Vitamin D (including both vitamin D2 and vitamin D3) obtained from sunlight or dietary sources is then converted to 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], catalyzed by vitamin D-25-hydroxylase in the liver. 25(OH)D is the major circulating form of vitamin D and is widely accepted as an index of vitamin D status in humans. However, it is biologically inert until it is hydroxylated in the kidney to form 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1α,25(OH)2D]. 1α,25(OH)2D is a lipid-soluble hormone that interacts with the vitamin D receptor (VDR) to exert a variety of functions, including genomic and non-genomic actions.

VITAMIN D AND CANCER

1α,25(OH)2D, the biologically active form of vitamin D, was originally discovered because of its effects on calcium and bone metabolism. It is now recognized that the hormone has activities in almost every tissue in the body. 1α,25(OH)2D3 implements this effect through binding to the nuclear VDR and then binding to a specific DNA sequence, the vitamin D response elements (VDREs)[16]. Via this genomic pathway, 1α,25(OH)2D3 can modulate gene expression in a tissue-specific manner, mainly leading to inhibition of cellular proliferation, induction of differentiation and apoptosis, which in turn, protect cells from malignant transformation and repress cancer cell growth.

However, the use of vitamin D to treat cancers has been impeded by lethal hypercalcemia induced by systemic administration of 1α,25(OH)2D3. To overcome this drawback, analogs of 1α,25(OH)2D3, exhibiting more potent growth inhibition but less calcemic effects, have been developed as anticancer drugs[17], and some of them have shown great results in pre-clinical studies. For example, Akhter et al[18] demonstrated that a 1α,25(OH)2D3 analog, EB 1089, exhibited an antiproliferative effect on colon cancer in a xenograft animal model. Abe-Hashimoto et al[19] showed that another 1α,25(OH)2D3 analog, OCT, displayed an antitumor effect on a xenograft model using MCF-7, a breast cancer cell line, in combination with tamoxifen. Furthermore, Polek et al[20] showed that another analog, LG190119, possessed antiproliferative activity when tested in an LNCaP prostate cancer cell xenograft model.

There are some limited clinical trials that show 1α,25(OH)2D3 and its analogs have antitumor effects in humans when used alone or in combination with other chemotherapy drugs. For example, Beer et al[21] conducted a phase II clinical trial in which they showed the combination of 1α,25(OH)2D3 and docetaxel could induce > 50% decline in PSA, a prostate cancer tumor marker, and improve survival of prostate cancer patients. However, most of the clinical trials only confirmed the less- or non-calcemic effect of 1α,25(OH)2D3 or its analog when used alone or in combination with other chemotherapy drugs without prolonging the survival of cancer patients. There are still many ongoing clinical trials attempting to demonstrate the antitumor effect of 1α,25(OH)2D3 and its analogs in humans. More effort is required in order to fully appreciate the clinical utilities of vitamin D-based therapies in treating human diseases, including cancers.

MECHANISMS OF VITAMIN D ACTIONS FOR CANCER TREATMENT

Vitamin D reduces the risk of cancer through its biologically active metabolite, 1α,25(OH)2D3, which regulates cellular proliferation and differentiation, inhibits angiogenesis, and induces apoptosis.

Stumpf et al[22], in 1979, reported that the VDR existed not only in the intestine, bone and kidney, but in almost all tissues in the body. Suda et al[23] (1982) first noted that 1α,25(OH)2D3 caused a marked inhibition of cell growth on VDR- positive M-1 leukemic cells. In the same year, Tanaka et al[24] reported that 1α,25(OH)2D3 showed the same effect on HL-60 leukemic cells, which had the VDR. Since then, many VDR-containing cancer cell lines, including prostate, colon, breast, lung, and melanoma, have shown growth inhibition when exposed to 1α,25(OH)2D3[1525–27].

The antiproliferative effects of 1α,25(OH)2D3 are mainly due to alterations in several key regulators of the cell cycle, culminating in dephosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein and arrest of cells in G0/G1[28]. Progression of the cell cycle is regulated by cyclins and their associated cyclin dependant kinases and cyclin dependant kinase inhibitors (CKIs). The CKI genes, such as p21 and/or p27, have VDRE within their promoter regions, and are genomic targets of the 1α,25(OH)2D3/VDR complex in many cell types, which in turn, induces G1 cell-cycle arrest and withdrawal from the cell cycle[29–31]. However, some genes are transcriptionally affected by 1α,25(OH)2D3 but lack VDREs in their promoter regions, which suggests that 1α,25(OH)2D3 induces indirect effects on cell-cycle regulation through another signaling pathway. For example, 1α,25(OH)2D3 could downregulate the expression of estrogen, epidermal growth factor, insulin-like growth factor 1, and keratinocyte growth factor and upregulate inhibitory growth factors, such as transformation growth factor-β[32–35].

1α,25(OH)2D3 can also induce differentiation to control tumor cell proliferation through the pathways of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, which is VDR dependent[36], and by suppression of interleukin 12 protein secretion[37], which is VDR independent.

Induction of apoptosis is another important function of 1α,25(OH)2D3, which represses the expression of the antiapoptotic protein, BCL2, and prosurvival protein, BCL-XL. 1α,25(OH)2D3 also enhances the expression of proapoptotic proteins such as BAX and BAD[38]. In addition to the BCL2 family, 1α,25(OH)2D3 can activate the caspase effector molecules directly to induce apoptosis[38]. Furthermore, it has been shown that 1α,25(OH)2D3, in combination with radiation or chemotherapeutic agents, causes an additive effect on cancer cell death[39–42].

Inhibition of angiogenesis is also an important anticancer mechanism of 1α,25(OH)2D3. 1α,25(OH)2D3 can repress endothelial cell growth in vitro and reduce angiogenesis in vivo[43–45]. The anti-angiogenic effects of 1α,25(OH)2D3 might subsequently lead to the inhibition of metastasis, as demonstrated in murine prostate and lung models treated with 1α,25(OH)2D3[4647].

The precise anticancer mechanisms of 1α,25(OH)2D3, including VDR-dependent and VDR-independent pathways are not fully understood. For the further use of 1α,25(OH)2D3 and its analogs in the treatment of cancers, there should be more studies addressing this issue to pave the way for the development of more potent 1α,25(OH)2D3 analogs.

ASSOCIATION OF VITAMIN D AND PANCREATIC CANCER-EPIDEMIOLOGICAL EVIDENCE

Epidemiologic studies have shown that vitamin D status, influenced by living at high or low latitude, solar UV exposure and dietary intake of vitamin D, was inversely associated with the incidence of some cancers such as prostate, colon and breast[48–50]. It was also reported that the risk of developing prostate, breast and colon cancer was decreased by 30%-50% if the serum concentration of 25(OH)D exceeded 50 nmol/L[5152]. Tangpricha et al[53] demonstrated that vitamin D deficiency enhanced the growth of MC-26 colon cancer xenografts in BALB/c mice, which supported the hypothesis that vitamin D sufficiency could reduce the proliferation of tumor cells in vivo.

To date, there have been only two epidemiological studies discussing the vitamin D status and the incidence of pancreatic cancer. One was conducted by Skinner et al[54] on U.S. nurses and health professionals, which demonstrated that higher dietary intake of vitamin D could be associated with lower incidence of pancreatic cancer. The other report, however, conducted in the observational cohort of the Finnish Alpha-Tocopheral Beta-Carotene (ATBC) trial, showed a discrepancy in results compared to the report by Skinner et al[54]. The ATBC data suggested that a higher serum concentration of 25(OH)D in male smokers was associated with a higher incidence of pancreatic cancer[55]. The reason behind these contradictory results was not clear, but they employed different measures of dietary intake of vitamin D versus 25(OH)D, and the participants in the ATBC trials were all male smokers, which might have contributed to the different conclusions in the two studies. To clarify this, more studies addressing the relationship between vitamin D status and incidence of pancreatic cancer are required.

VITAMIN D AND PANCREATIC CANCER-BIOCHEMICAL EVIDENCE

While the precise anticancer mechanisms, including VDR-dependent and VDR-independent actions, induced by 1α,25(OH)2D3 still require further investigation, it is known that in pancreatic cancer cells, 1α,25(OH)2D3 induces the expression of p21 and p27 and inhibits the production of cyclins (D1, E and A) and cyclin dependent kinases 2 and 4, which in turn, elicit cell cycle arrest in G0/G1in vitro[56]. Similar effects have been observed with 19-nor-1α,25(OH)2D2 (Paricalcitol) in human pancreatic cancer cells in vitro and in vivo by upregulating the expressions of p21 and p27[57] (Figure 1).

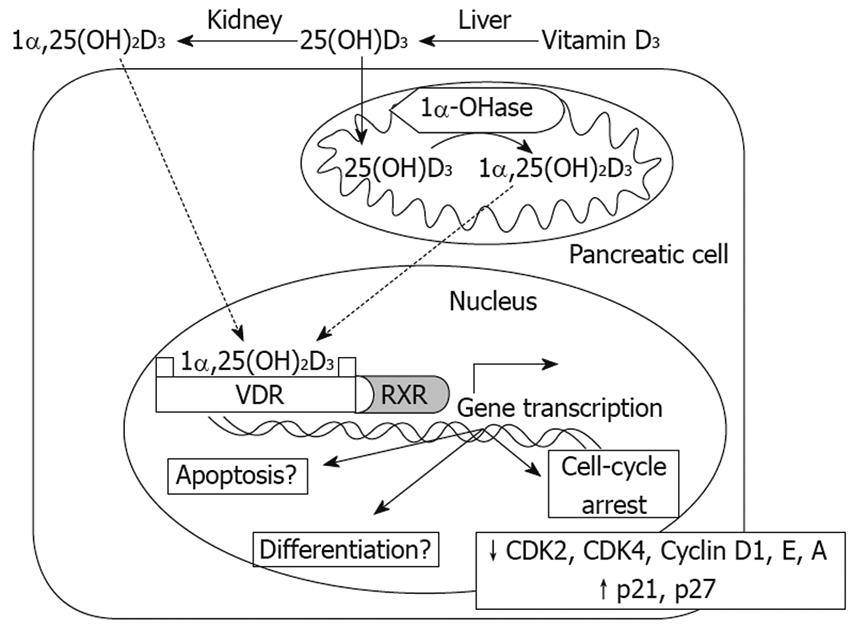

Figure 1 Mechanisms of Vitamin D3 action on pancreas cells.

Both 1,25(OH)2D3 and 25(OH)D3 can enter pancreas cells, where 25(OH)D3 can be converted to 1,25(OH)2D3 by 1α-OHase. 1,25(OH)2D3 can bind the VDR and further combine with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) to form a heterodimer, VDR-RXR. The VDR-RXR heterodimer binds to specific vitamin D response elements located in the promoter region of vitamin D-responsive genes, which in turn induces gene transcription. So far, in terms of pancreas cells, inhibition of CDK2, CDK4, Cyclin D1, Cyclin E, Cyclin A and upregulation of p21 and p27 have been demonstrated, leading to a block in the cell cycle at G0/G1. Regarding induction of differentiation, apoptosis and other anticancer mechanisms, further studies are required.

Currently, very little is known about the mechanisms of vitamin D actions on pancreatic cancer cells. More emphasis in this area is needed, because very few efficient therapeutic options are available to benefit pancreatic cancer survival.

POTENTIAL OF VITAMIN D ANALOGS FOR PANCREATIC CANCER TREATMENT

Since the VDR exists in almost every tissue of the body[22] and 1α,25(OH)2D3 exhibits growth inhibitory effects on may different types of cancer cells, several studies have been performed to investigate the anticancer effect of vitamin D and its analogs on pancreatic cancer cells during the past two decades. For example, Kawa et al[56] reported that 22-oxa-1α,25(OH)2D3, a 1α,25(OH)2D3 analog, caused growth inhibition in three pancreatic cancer cell lines and inhibited the growth of a BxPC-3 tumor in a xenograft nude mice model[58]. Colston et al[59] demonstrated that another 1α,25(OH)2D3 analog, EB 1089, exhibited more potent antitumor effects than 1α,25(OH)2D3 on the GER cell line, a human pancreatic cancer cell line, in vitro and in vivo. Pettersson et al[60] also reported that EB 1089 induced greater tumor growth inhibition than 9-cis-retinoic acid in vitro. These two pre-clinical studies therefore suggested that EB 1089 might be a promising vitamin D analog for further clinical trials in pancreatic cancer patients. However, in a phase II clinical trial, which is also the only clinical trial studying the use of vitamin D analogs against pancreatic cancer, EB 1089 given once daily orally failed to significantly improve patient survival, although most patients tolerated the daily orally dose of 10-15 &mgr;g of the drug well, without causing hypercalcemia[61].

With the knowledge that 19-nor-1α,25(OH)2D2 (Paricalcitol) is a Federal Drug Administration approved drug for the treatment and prevention of secondary hyperparathyroidism associated with chronic kidney disease[62], and this analog has comparable growth inhibitory effects as 1α,25(OH)2D3 in human prostate cancer cells in vitro[63], Schwartz et al[57] studied the same analog in human pancreatic cancer cells in vitro and demonstrated that it also inhibited the proliferation of these cells. Given the fact that Paricalcitol has been shown to be less calcemic than 1α,25(OH)2D and few therapeutic options for pancreatic cancer patients are available, it is worth further exploration as an anticancer drug for pancreatic cancer.

In addition to using synthetic 1α,25(OH)2D3 analogs to treat pancreatic cancer in an effort to avoid hypercalcemia, another strategy is the employment of inactive prohormone 25(OH)D3 (Figure 1). This is based on the finding that many normal and cancerous cells, including prostate cell lines and primary cultures of prostate cells, possess 25(OH)D-1α-hydroxylase (1α-hydroxylase or CYP27b1), the enzyme responsible for the conversion of 25(OH)D3 to 1α,25(OH)2D3[26], and CYP27b1 has been proposed as a tumor suppressor[64]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that 25(OH)D3 had a comparable tumor growth inhibitory effect to 1α,25(OH)2D3 on primary cultures of prostate cells[6365]. These findings led to a subsequent study demonstrating that CYP27b1 activity was also expressed in pancreatic cancer cells and the growth of these cancer cells was inhibited in the presence of 25(OH)D3[66]. Given the fact that the conversion of 25(OH)D3 to 1α,25(OH)2D3 occurs within the cell, and the 1α,25(OH)2D3 formed acts in a autocrine/paracrine fashion[2663–65], systemic administration of 25(OH)D3 might greatly minimize the risk of hypercalcemia. 25(OH)D3 has been approved by the Federal Drug Administration to treat vitamin D deficiency in humans; therefore, 25(OH)D3 could be another attractive candidate for clinical trials in pancreatic cancer patients.

CONCLUSION

Abundant evidence indicates that 1α,25(OH)2D3 has antiproliferative, pro-differentiative, apoptotic and antiangiogenic activities in different types of tumor cells. In different cancer cell types, 1α,25(OH)2D3 can induce the expression of various molecular markers to regulate cell growth. Even in the same tissue, different cell types might exhibit heterogeneous responses to the addition of 1α,25(OH)2D3. It is known that 1α,25(OH)2D3 and its analogs can inhibit pancreatic cancer cell growth in vitro[5659] via activation of p21 and p27, which in turn influence cell cycle progression and arrest cells in G0/G1. So far, the only pancreatic cancer clinical trial using a 1α,25(OH)2D3 analog, EB 1089[61], did not show significant prolongation of survival. However, a preclinical study with 19-nor-1α,25(OH)2D2 (Paricalcitol) in pancreatic cancer cells[60] has provided some encouraging results and might lead to further clinical trials. Moreover, given the fact that pancreatic cancer cells posses 1α-hydroxylase (CYP27b1) activity and can convert the prohormone 25(OH)D, which has a low risk of inducing hypercalcemia even at high concentrations, into 1α,25(OH)2D within the cells and thereby inhibiting pancreatic cancer cell growth in a autocrine/paracrine fashion[2663–65], prohormone 25(OH)D-based therapy might be another attractive treatment strategy for pancreatic cancer in the future.

Peer reviewers: Dario Conte, Professor, GI Unit - IRCCS Osp. Maggiore, Chair of Gastroenterology, Via F. Sforza, 35, Milano 20122, Italy; Ian C Roberts-Thomson, Professor, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, The Queen Elizabeth Hospital, 28 Woodville Road, Woodville South 5011, Australia