Published online Jun 28, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3065

Revised: May 21, 2009

Accepted: May 28, 2009

Published online: June 28, 2009

Iatrogenic perforation of esophageal cancer or cancer of the gastroesophageal (GE) junction is a serious complication that, in addition to short term morbidity and mortality, significantly compromises the success of any subsequent oncological therapy. Here, we present an 82-year-old man with iatrogenic perforation of adenocarcinoma of the GE junction. Immediate surgical intervention included palliative resection and GE reconstruction. In the case of iatrogenic tumor perforation, the primary goal should be adequate palliative (and not oncological) therapy. The different approaches for iatrogenic perforation, i.e. surgical versus endoscopic therapy are discussed.

- Citation: Gillen S, Friess H, Kleeff J. Palliative cardia resection with gastroesophageal reconstruction for perforated carcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(24): 3065-3067

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i24/3065.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.3065

Iatrogenic perforation of cancer of the esophagus or the gastroesophageal (GE) junction is a potentially life-threatening complication. Its incidence has increased most likely because of more aggressive palliative endoscopic therapy[1], and the current widespread use of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) for accurate preoperative staging[2]. Therapy and management, i.e. conservative versus surgical treatment remains controversial, with successful early outcome being described for both approaches[34]. Irrespective of the treatment, iatrogenic (or spontaneous) perforation of the tumor has been shown to be a strong negative predictive factor for long-term survival. Therapy should therefore focus on the immediate and efficient control of the perforation (such as drainage, stenting or resection), and on a satisfactory quality of life rather than on oncologically adequate treatment.

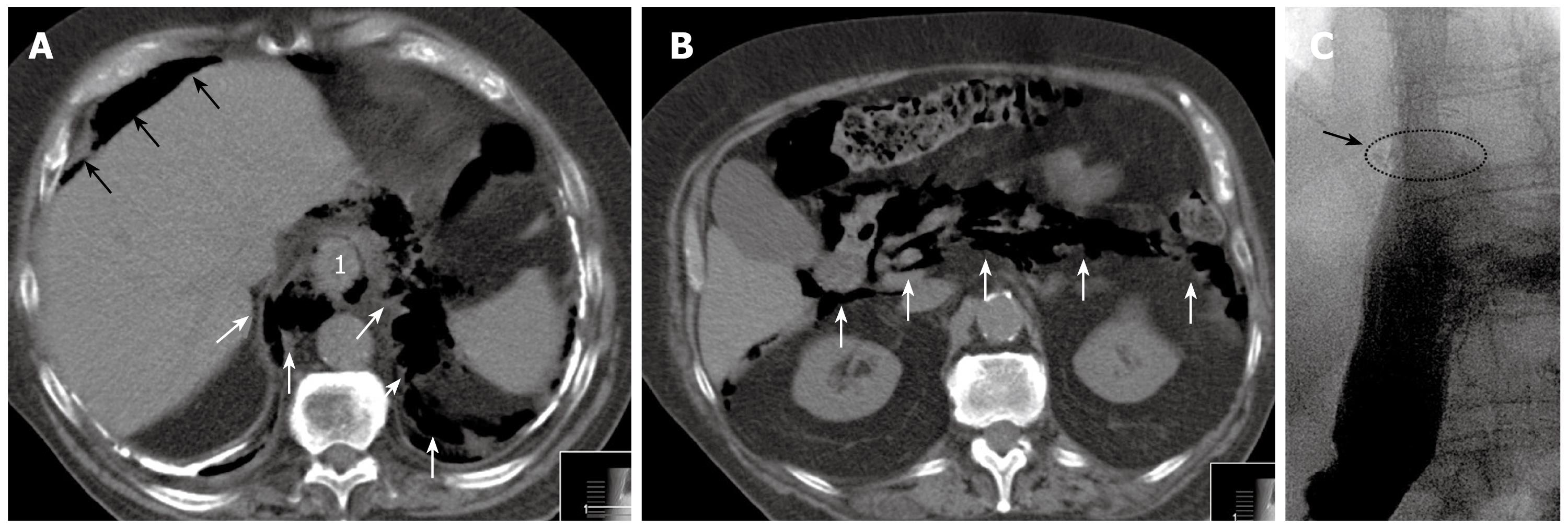

An 82-year-old man was referred to our department with perforation of a subtotal stenosing adenocarcinoma of the GE junction. Previous symptoms were vomiting and weight loss of 6 kg in the last 6-8 wk. In the initial computed tomography (CT) scan, no signs of distant metastases were present. The patient had a history of tuberculosis 40 years ago, and CT revealed massive pleural calcifications. He was on oral anticoagulation therapy because of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. To complete the staging, EUS was performed after endoluminal dilation of the tumor and passage into the stomach. EUS demonstrated an uT3 stage with suspicious lymph nodes. Following the EUS procedure, the patient developed severe abdominal pain. Subsequent CT showed air in the distal mediastinum, as well as in the retroperitoneal and intraperitoneal space (Figure 1A and B). After referral, the patient presented in a reduced general condition with acute abdomen, and signs of sepsis (tachycardia, hypotension and tachypnea). Infection signs were slightly increased: C-reactive protein 0.6 mg/dL (normal < 0.5 mg/dL), leukocytes 11.0 G/L (normal 4-9 G/L). As a result of the clinical symptoms, free intra-abdominal air, and subtotal stenosing tumor, we decided against initial endoscopic intervention and for immediate explorative laparotomy (10 h after the EUS procedure).

Intraoperatively, the tumor was localized exactly at the GE junction, with a dorsal perforation just proximal to the tumor. The tumor was removed completely by resection of the cardia and 5 cm of the distal esophagus. For reconstruction, a partial proximal gastric tube was constructed (20-25 cm in length with a diameter of 4-5 cm) using linear staplers (50 mm Proximate Linear Cutter; Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA). The gastric antrum was opened from the ventral aspect and a circular stapler (25 mm CEEA circular stapler; Covidien Autosuture, Mansfield, MA, USA) was introduced to anastomose the distal esophagus with the proximal ventral portion of the gastric tube. Since the small bowel mesentery was rather short and not mobile, we decided against total gastrectomy and esophagojejunal reconstruction in this emergency situation. An oncological lymph node dissection was not carried out in this elderly and multimorbid patient.

The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient received intravenous antibiotics (imipenem/cilastatin, 3 × 500 mg/d), but no antifungal agent, for 7 d. A water-soluble contrast medium swallow on postoperative day 7 showed no signs of stenosis or anastomotic insufficiency (Figure 1C). The patient was put on full diet following this examination, and was discharged on postoperative day 14. On a further follow-up visit after 4 wk, the patients did not complain of reflux or dysphagic symptoms. Final histopathological examination revealed a perforated pT3 adenocarcinoma of the GE junction. The case was discussed interdisciplinarily, and no additive/palliative therapy was initiated because of the low WHO performance status of 2-3.

Perforation in patients with potentially curative resectable cancer of the esophagus or GE junction reduces dramatically the chance of long-term survival. Immediate therapy should target the potential septic focus either by drainage and stenting the lesion, or by resection. Secondary considerations include oncologically adequate treatment and reconstruction of the GE passage that offers the best quality of life.

The approach of conservative versus surgical therapy in cases of iatrogenic perforation has shifted more towards conservative therapy, together with the development of novel endoscopic stenting possibilities[1]. The question of whether iatrogenic perforations are best managed by surgery or endoscopy has recently been addressed by two large studies. Di Franco et al[5] have examined 48 patients with iatrogenic perforation of esophageal cancer. Sixteen patients were treated by oncological esophagectomy, and 32 were treated conservatively because of advanced disease in 17 and poor performance status in 15. The authors demonstrated that all patients in the resection group died of recurrent disease and more than half of them died within the first year after surgery. The difference in survival between the resected and non-resected group of patients was not significant. Similarly, Jethwa et al[6] have analyzed 83 iatrogenic perforations during diagnostic endoscopy, of which, 27 were managed by surgery. The median survival in the whole cohort was 72 d. There was a trend for longer survival in patients undergoing surgery. However, the high 30-d mortality of nearly 40% and the poor survival in the surgical and non-surgical group shows that even rapid surgical treatment often fails to change the natural course of the disease at this stage. Together, both studies suggest that the primary approach to perforated esophageal cancer should be conservative.

However, under certain conditions, the conservative approach is not feasible; e.g., the perforation is too extensive for adequate stent therapy, or, as in our case, the tumor is (subtotal) stenosing, making successful stent therapy exceedingly difficult. Other indications for a surgical approach include extensive peritonitis or mediastinitis that cannot be drained adequately by interventional drainage placement. Irrespective of the indication for surgery, it should entail the least invasive measure that offers the greatest chance of immediate survival and the best quality of life for the remaining time period. Thus, whenever possible, the esophago-intestinal continuity should be re-established.

In the present case, we opted for reconstruction using an end-to-side esophago-gastrostomy. Limited resection of the cardia and the distal esophagus has been described particularly for early tumors of the GE junction. While this procedure is safe and effective, and does not seem to result in postgastrectomy symptoms or microgastria[7], other reports have highlighted the long-term risk of reflux esophagitis when using esophagogastrostomy for reconstruction[8]. Other options include the Merendino procedure or total gastrectomy with esophago-jejunostomy reconstruction[9]. However, while the former one would seem too time consuming and technically demanding in an emergency situation[8], the latter requires an adequate mobile jejunum, and there is evidence of an early clinical benefit from formation of a gastric reservoir[9].

In conclusion, the management of esophageal perforation in the context of an underlying malignancy demands an individual approach that depends upon the site and etiology of the perforation. Irrespective of the therapeutic approach, the prognosis after tumor perforation is dismal. Therefore, the best palliative procedure has to be chosen, which is in most instances, a conservative one with drainage and stenting, or limited surgery with re-establishment of the esophago-intestinal continuity.

| 1. | Siersema PD. New developments in palliative therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:959-978. |

| 2. | Bergman JJ. The endoscopic diagnosis and staging of oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:843-866. |

| 3. | Richardson JD. Management of esophageal perforations: the value of aggressive surgical treatment. Am J Surg. 2005;190:161-165. |

| 4. | Vogel SB, Rout WR, Martin TD, Abbitt PL. Esophageal perforation in adults: aggressive, conservative treatment lowers morbidity and mortality. Ann Surg. 2005;241:1016-1021; discussion 1021-1023. |

| 5. | Di Franco F, Lamb PJ, Karat D, Hayes N, Griffin SM. Iatrogenic perforation of localized oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg. 2008;95:837-839. |

| 6. | Jethwa P, Lala A, Powell J, McConkey CC, Gillison EW, Spychal RT. A regional audit of iatrogenic perforation of tumours of the oesophagus and cardia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:479-484. |

| 7. | Hirai T, Matsumoto H, Iki K, Hirabayashi Y, Kawabe Y, Ikeda M, Yamamura M, Hato S, Urakami A, Yamashita K. Lower esophageal sphincter- and vagus-preserving proximal partial gastrectomy for early cancer of the gastric cardia. Surg Today. 2006;36:874-878. |

| 8. | Tokunaga M, Ohyama S, Hiki N, Hoshino E, Nunobe S, Fukunaga T, Seto Y, Yamaguchi T. Endoscopic evaluation of reflux esophagitis after proximal gastrectomy: comparison between esophagogastric anastomosis and jejunal interposition. World J Surg. 2008;32:1473-1477. |

| 9. | McCulloch P. The role of surgery in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:767-787. |