Published online Jun 28, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3055

Revised: May 21, 2009

Accepted: May 28, 2009

Published online: June 28, 2009

AIM: To investigate immunosuppressive agents used to treat inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in East China.

METHODS: A retrospective review was conducted, involving 227 patients with IBD admitted to Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University from June 2000 to December 2007. Data regarding demographic, clinical characteristics and immunosuppressants usage were analyzed.

RESULTS: A total of 227 eligible patients were evaluated in this study, including 104 patients with Crohn’s disease and 123 with ulcerative colitis. Among the patients, 61 had indications for immunosuppressive agents use. However, only 21 (34.4%) received immunosuppressive agents. Among the 21 patients, 6 (37.5%) received a subtherapeutic dose of azathioprine with no attempt to increase the dosage. Of the 20 patients that received immunosuppressive agent treatment longer than 6 mo, 15 patients went into remission, four patients were not affected and one relapsed. Among these 20 patients, four patients suffered from myelotoxicity and one suffered from hepatotoxicity.

CONCLUSION: Immunosuppressive agents are used less frequently to treat IBD patients from East China compared with Western countries. Monitoring immunosuppressive agent use is recommended to optimize dispensation of drugs for IBD in China.

- Citation: Huang LJ, Zhu Q, Lei M, Cao Q. Current use of immunosuppressive agents in inflammatory bowel disease patients in East China. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(24): 3055-3059

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i24/3055.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.3055

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), is a chronic disorder of the gastrointestinal tract. There have been no large scale epidemiological studies on the incidence and prevalence of IBD in China, but reports indicate that rates are increasing. According to data collected from multiple hospitals, the prevalence rate of UC and CD can be speculatively estimated to be 11.6/105 and 1.4/105, respectively; however, the numbers may be underestimated[1]. An investigation from one hospital showed that the definitive cases of IBD during the past 10 years have increased five-fold[2].

Immunosuppressive agents, such as Azathioprine (AZA), play an essential role in drug therapy of IBD. Evidence-based medicine has shown that immunosuppressive agents can control active inflammation, allow for the withdrawal of steroids, and ultimately maintain long-term remission of IBD[3–5]. However, great interpatient variability has been found when assessing the efficacy and toxicity of these drugs. In the treatment of active disease, about 2/3 of the patients achieve remission, but this results is not achieved in approximately 15% of cases, and serious drug toxicity leads to cessation of therapy in 9%-28% of patients, such as myelotoxicity and hepatotoxicity[67]. Uncertainty regarding the risk of interpatient variability and serious drug toxicity prevent the use of AZA and other immunosuppressants, and therefore affects the quality of care in IBD patients. Domestically, the paradox is quite a problem. Currently, there are no reports about the status of usage of AZA and other immunosuppressive agents in Chinese IBD patients.

Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital is a teaching hospital affiliated to Zhejiang University, China. Together with 12 other large hospitals and numerous smaller district hospitals, it provides health care to 48 million people living in Zhejiang Province in eastern China. Our IBD study group has set up an IBD database to collect IBD patients’ data in East China. The purpose of the current study was to do a retrospective study of the therapeutic status of immunosuppressive agents, such as AZA used in patients with IBD in hospitals, to investigate the therapeutic implications of IBD in eastern China, to arouse the attention of clinicians, to apply immunosuppressive drugs optimally and to enhance the quality of therapy delivered to IBD patients.

IBD patients admitted to Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, from June 2000 to December 2007, were enrolled in this study.

The diagnosis of IBD was confirmed by the criteria established by Chinese Society of Gastroenterology[8] in 2000 and the guidelines issued by the Clinical Services Committee of the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG)[9] in 2004. Patients not under the care of a gastroenterologist were excluded.

A retrospective review was performed. Clinical data on demographic information, clinical characteristics of IBD patients, as well as endoscopic, radiologic, surgical and pathological records, confirmed diagnoses, duration and severity of disease, and use of immunomodulatory agents were collected from the inpatient and follow-up clinic visit records and collated in an IBD database.

The data were expressed as mean values, and the enumeration data were expressed by percentages. All statistical analyses were performed by SPSS V 13.0 (Statistical Product and Service Solutions).

According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 104 patients with CD and 123 patients with UC were enrolled in the study. All the patients were Han Chinese.

UC was categorized by extent, activity and severity of disease. Extent of disease at diagnosis was defined macroscopically by the proximal limit of inflammation at colonoscopy and was divided into the following four categories: (1) Proctitis, inflammation confined to the rectum only; (2) Distal colitis, inflammation involving to the rectum and sigmoid colon; (3) Left-sided colitis, inflammation extending the rectum to and including the splenic flexure; (4) Extensive colitis, inflammation proximal to the splenic flexure.

Patients with Crohn’s disease were classified by age of onset, disease location and behaviour according to the Vienna classification[10]. Disease activity was assessed using the Harvey-Bradshaw index (HBI) for CD and the Sutherland index for UC. Active disease was defined as a HBI value ≥ 5 or a Sutherland index ≥ 3. Severity was broadly divided into mild, moderate or severe according to the Truelove & Witts’ criteria for UC and the criteria established by the Chinese Society of Gastroenterology for CD.

Severe UC was defined as the passage of ≥ 6 bloody stools daily with one or more of the following criteria: temperature > 37.8°C, pulse > 90/min, haemoglobin < 10.5 g/dL, or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) > 30 mm/h[11].

Mild CD was defined when the patient had no fever, abdominal tenderness, abdominal mass and obstruction, while severe CD was defined when the patient had persistent high fever, weight loss, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, anemia, and complications. Characteristics of the patients and the information about the location of disease are given in Table 1.

| Crohn’s disease | Ulcerative colitis | |

| Number of patients | 104 | 123 |

| Female | 42 (40.4%) | 56 (45.5%) |

| Age (yr) | 36 (13-70) | 45 (15-80) |

| Disease duration (yr) | 4.8 (0.5-24) | 5.5 (0.5-23) |

| Non-smoking | 82 (78.8%) | 90 (73.2%) |

| Severity, n (%) | ||

| Mild | 24 (23.1) | 62 (50.4) |

| Moderate | 51 (49) | 42 (34.1) |

| Severe | 29 (27.9) | 19 (15.5) |

| Disease distribution, n (%) | ||

| Small intestine | 44 (42.3) | |

| Ileum and colon | 17 (16.3) | |

| Colon | 40 (38.5) | |

| Upper digestive tract | 3 (2.9) | |

| Disease distribution (UC), n (%) | ||

| Distal colon | 41 (33.3) | |

| Left side colon | 24 (19.5) | |

| Systemic or pan-colon | 58 (47.2) | |

| History of any intestinal operation | 46 (44.2) | 5 (4.1) |

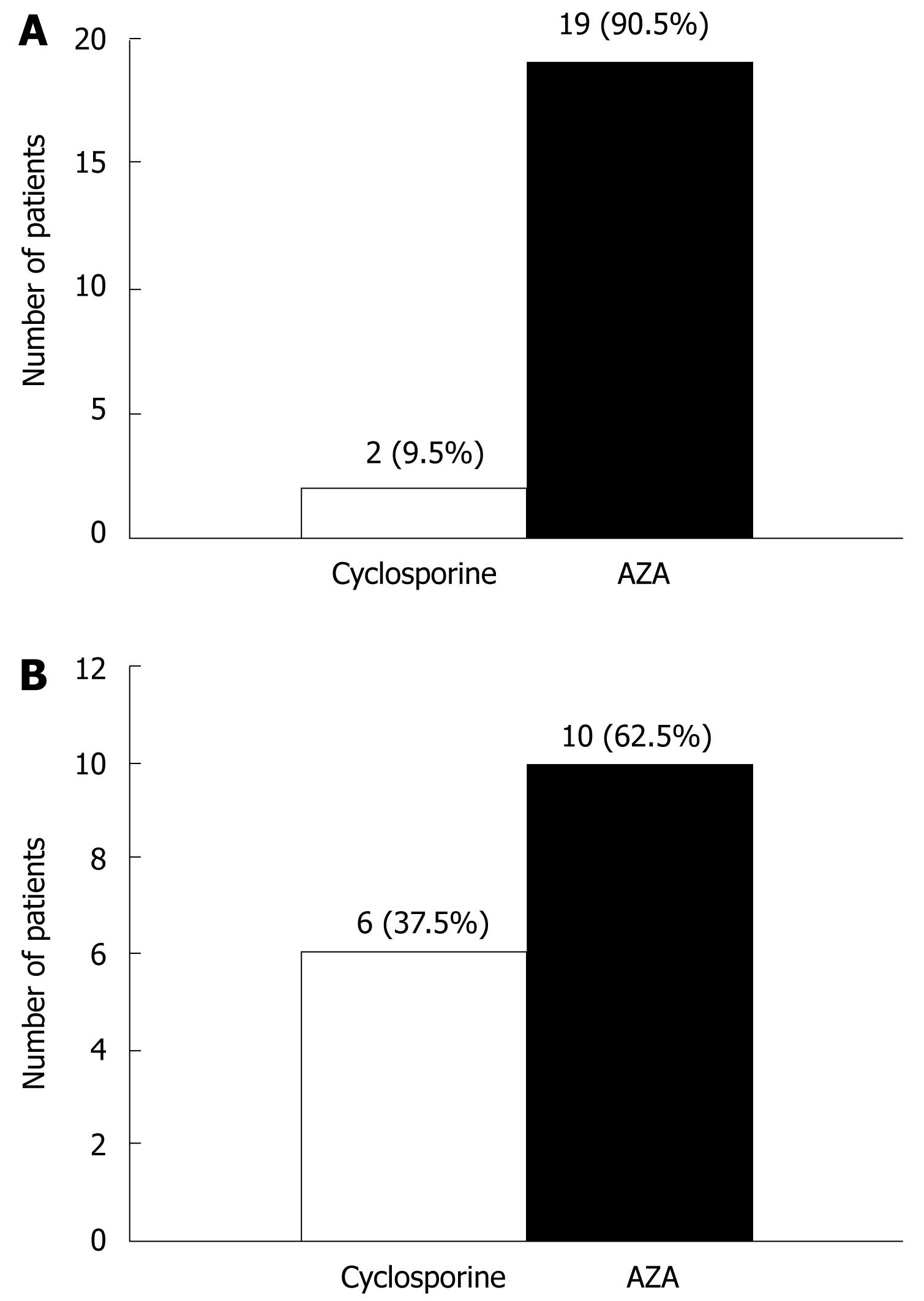

Of the 227 patients, 61were administered immunosuppressant agents. Among these patients 27 (44.3%) were steroid-dependent (refers to a relapse when the steroid dose is reduced below 20 mg/d, or within 6 wk of stopping steroids), 6 (9.8%) were steroid-refractory (refers to active disease in spite of an adequate dose and duration of prednisolone > 20 mg/d for more than 2 wk) and 28 (45.9%) had post-surgery fistulating CD. Twenty-one patients (21/61, 34.4%) received immunosuppressive agents (19 cases with AZA, two cases with cyclosporin) as shown in Figure 1A. The mean dose of AZA was 1.47 mg/kg per day (range 0.83-2.22 mg/kg per day). A suboptimal dose of AZA was defined as a dose less than 1.5 mg/kg per day in the absence of myelotoxicity or hepatotoxicity. AZA-related myelotoxicity is defined as WBC < 3.0 × 109/L or neutrophil < 1.5 × 109/L, while AZA-related hepatotoxicity is defined as ALT and/or GGT levels greater than 5 times the upper normal limit, or ALP levels greater than 3 times the upper normal limit, excluding viral hepatitis. When withdrawing AZA or reducing the dose, the above indexes recover to normal. According to this criterion, among the 19 patients treated with AZA, there were two with myelotoxicity and one with hepatotoxicity, before the clinician adjusted the dosage. The other 16 residual cases received AZA therapy, and six of those cases (37.5%) received subtherapeutic therapy, with no attempt to increase this dosage (Figure 1B).

Of the 21 patients administered immunosuppressant therapy, 21 patients maintained these regimen for more than 6 mo, and one patient withdrew from drug without a recommendation by a clinician 3 mo later.

The effectiveness of the immunosuppressant therapy (disease remission) is defined as follows: for Crohn’s disease, the HBI value was less than five or for UC the Sutherland index was less than three. According to this definition, of the 20 patients who received immunosuppressant therapy for more than 6 mo, 15 (75%) patients went into remission, four (20%) patients had no benefit and one (5%) relapsed.

According to the definitions of AZA-related myelotoxicity and hepatotoxicity, four (20%) patients suffered from myelotoxicity (two cases occurred within 3 mo after receiving AZA therapy; one case each occurred one and two years after drug therapy) and one (5%) patient suffered from hepatotoxicity.

IBD, which includes CD and UC, is a complicated disease of the digestive tract. In recent years, because of the rapid development of evidence-based medicine, the therapy guidelines of IBD in China and abroad have been updated constantly. Reddy et al[12] analyzed the therapeutic condition of American patients with IBD according to the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) practice guidelines[1314]. They found that the dose of aminosalicylic acid agents was not adequate and enema therapy and immunosuppressive agents were not applied effectively[1314]. With the lack of relative data in China, we carried out this study to reflect the current therapeutic condition of patients with IBD in eastern China.

Although glucocorticoids are effective in the induction of remission for IBD, more than 20% of patients may be steroid-refractory or become steroid-dependent[15–17]. Meta-analyses showed that glucocorticoids are not effective for medical maintenance. The frequency and severity of well-recognized adverse effects also preclude their long-term use.

Immunosuppressive agents such as AZA can induce and maintain remission of IBD and have steroid sparing effects in patients who are steroid dependent or who have refractory IBD[718–20].

In our study, the use of immunosuppressive agents was restricted to a minority of IBD patients (19.6%) who adapted to use these drugs, which is distinctly less frequent compared with that in Western countries. Furthermore, more than half of the patients did not receive recommended doses of AZA. We found that the percentage of serious drug toxicity was 5/20 in AZA therapy. Because of the lack of data from large-scale studies in China, the adverse reaction rate of AZA in Han nationality Chinese with IBD is not clear. Results of our study are consistent with the conclusions reported outside of China[21].

At present, many researchers presume that interpatient and interracial variability, which are based on thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) gene polymorphisms and enzyme activity, exist and affect the efficacy and toxicity of AZA. Whether TPMT gene polymorphisms and enzyme activity have their own characteristics in this Han Chinese population, and how they affect the efficacy and toxicity of drug still remains to be seen. Because large-scale studies in China are not available, we do not have relevant data about TPMT gene polymorphisms and enzyme activity, relative studies about the efficacy and toxicity of drugs when given with TPMT, relevant screening methods for high risk groups before using drug or relative monitoring methods for the efficacy and toxicity of drug. Serious drug toxicities, such as myelotoxicity and hepatotoxicity, deter the use and prevent achieving the optimal dose of immunosuppressive agents by clinicians. Experience abroad has shown that AZA can be safely used for treatment of IBD[22–24].

Recently, TPMT and its genotype have been applied to predict the efficacy and toxicity of drugs, which can provide some guidance for clinicians and reduce the incidence of drug toxicity in Western countries[25–29]. Meanwhile, studies have shown that examining TPMT enzyme activity may decrease the overall medical cost in Europe and America[3031].

Therefore, developing a study of TPMT polymorphisms and enzyme activity in Han nationality Chinese with IBD and clarifying the correlation between the efficacy and toxicity of drugs and TPMT will provide theoretical evidence for the clinical application of immunosuppressive agents, such as AZA. Developing techniques to examine TPMT polymorphisms and enzyme activity, as well as concentrations of AZA’s metabolites, will be helpful to screen patients in high risk groups, reduce the incidence of toxicity because of drugs, improve the rationality and reliability of pharmacotherapy, setup an individualization of therapeutic schedules, and broaden the therapeutic modalities for IBD patients.

Immunosuppressive agents are well established in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. The goals of using this class of medication are to control active inflammation, allow for the withdrawal of steroids, and ultimately to maintain long-term remission of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Immunosuppressive agents, such as Azathioprine (AZA), play an essential role in the pharmacotherapy of IBD. Evidence-based medicine proved that immunosuppressive agents such as AZA can induce and maintain remission of IBD and have steroid sparing effects in patients who are steroid dependent or who have refractory IBD. However, experience abroad has shown great interpatient variability in the efficacy and toxicity of these drugs.

The use of immunosuppressive agents in IBD patients in China has not been reported. The authors designed this study to address this problem and provide data to improve the quality of IBD treatment in China.

This is an important study and interesting topic, especially for an Asian readership.

| 1. | OuYang Q, Hu PJ, Qian JW, Zheng JJ, Hu RW. Chinese Society of Gastroenterology: Management of inflammatory bowel disease. Zhonghua Xiaohua Zazhi. 2007;12:488-495. |

| 2. | Cao Q, Si JM, Gao M, Zhou G, Hu WL, Li JL. Clinical presentation of inflammatory bowel disease: a hospital based retrospective study of 379 patients in eastern China. Chin Med J (Engl). 2005;118:747-752. |

| 3. | Pearson DC, May GR, Fick GH, Sutherland LR. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine in Crohn disease. A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:132-142. |

| 4. | Kirk AP, Lennard-Jones JE. Controlled trial of azathioprine in chronic ulcerative colitis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1982;284:1291-1292. |

| 5. | Hawthorne AB, Logan RF, Hawkey CJ, Foster PN, Axon AT, Swarbrick ET, Scott BB, Lennard-Jones JE. Randomised controlled trial of azathioprine withdrawal in ulcerative colitis. BMJ. 1992;305:20-22. |

| 6. | Gearry RB, Barclay ML, Burt MJ, Collett JA, Chapman BA. Thiopurine drug adverse effects in a population of New Zealand patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13:563-567. |

| 7. | Fraser AG, Orchard TR, Jewell DP. The efficacy of azathioprine for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a 30 year review. Gut. 2002;50:485-489. |

| 8. | OuYang Q, Pan GZ, Wen ZH, Wan XH, Hu RW, Lin SR, Hu PJ. Chinese Society of Gastroenterology: Management of inflammatory bowel disease. Zhonghua Neike Zazhi. 2001;40:138-141. |

| 9. | Carter MJ, Lobo AJ, Travis SP. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2004;53 Suppl 5:V1-16. |

| 10. | Gasche C, Scholmerich J, Brynskov J, D'Haens G, Hanauer SB, Irvine EJ, Jewell DP, Rachmilewitz D, Sachar DB, Sandborn WJ. A simple classification of Crohn's disease: report of the Working Party for the World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna 1998. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2000;6:8-15. |

| 11. | Travis SP, Farrant JM, Ricketts C, Nolan DJ, Mortensen NM, Kettlewell MG, Jewell DP. Predicting outcome in severe ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1996;38:905-910. |

| 12. | Reddy SI, Friedman S, Telford JJ, Strate L, Ookubo R, Banks PA. Are patients with inflammatory bowel disease receiving optimal care? Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1357-1361. |

| 13. | Kornbluth A, Sachar DB. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults. American College of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:204-211. |

| 14. | Hanauer SB, Meyers S. Management of Crohn's disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:559-566. |

| 15. | Faubion WA Jr, Loftus EV Jr, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. The natural history of corticosteroid therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:255-260. |

| 16. | Ho GT, Chiam P, Drummond H, Loane J, Arnott ID, Satsangi J. The efficacy of corticosteroid therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: analysis of a 5-year UK inception cohort. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:319-330. |

| 17. | Tung J, Loftus EV Jr, Freese DK, El-Youssef M, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd, Harmsen WS, Sandborn WJ, Faubion WA Jr. A population-based study of the frequency of corticosteroid resistance and dependence in pediatric patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:1093-1100. |

| 18. | Chebli JM, Gaburri PD, De Souza AF, Pinto AL, Chebli LA, Felga GE, Forn CG, Pimentel CF. Long-term results with azathioprine therapy in patients with corticosteroid-dependent Crohn's disease: open-label prospective study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:268-274. |

| 19. | Holtmann MH, Krummenauer F, Claas C, Kremeyer K, Lorenz D, Rainer O, Vogel I, Böcker U, Böhm S, Büning C. Long-term effectiveness of azathioprine in IBD beyond 4 years: a European multicenter study in 1176 patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:1516-1524. |

| 20. | Caprilli R, Angelucci E, Cocco A, Viscido A, Annese V, Ardizzone S, Biancone L, Castiglione F, Cottone M, Meucci G. Appropriateness of immunosuppressive drugs in inflammatory bowel diseases assessed by RAND method: Italian Group for IBD (IG-IBD) position statement. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:407-417. |

| 21. | Lamers CB, Griffioen G, van Hogezand RA, Veenendaal RA. Azathioprine: an update on clinical efficacy and safety in inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1999;230:111-115. |

| 22. | Tanis AA. Azathioprine in inflammatory bowel disease, a safe alternative? Mediators Inflamm. 1998;7:141-144. |

| 23. | Connell WR, Kamm MA, Ritchie JK, Lennard-Jones JE. Bone marrow toxicity caused by azathioprine in inflammatory bowel disease: 27 years of experience. Gut. 1993;34:1081-1085. |

| 24. | Fraser AG, Orchard TR, Robinson EM, Jewell DP. Long-term risk of malignancy after treatment of inflammatory bowel disease with azathioprine. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1225-1232. |

| 25. | Yates CR, Krynetski EY, Loennechen T, Fessing MY, Tai HL, Pui CH, Relling MV, Evans WE. Molecular diagnosis of thiopurine S-methyltransferase deficiency: genetic basis for azathioprine and mercaptopurine intolerance. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:608-614. |

| 26. | Cuffari C, Dassopoulos T, Turnbough L, Thompson RE, Bayless TM. Thiopurine methyltransferase activity influences clinical response to azathioprine in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:410-417. |

| 27. | Dubinsky MC, Lamothe S, Yang HY, Targan SR, Sinnett D, Théorêt Y, Seidman EG. Pharmacogenomics and metabolite measurement for 6-mercaptopurine therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:705-713. |

| 28. | Kaskas BA, Louis E, Hindorf U, Schaeffeler E, Deflandre J, Graepler F, Schmiegelow K, Gregor M, Zanger UM, Eichelbaum M. Safe treatment of thiopurine S-methyltransferase deficient Crohn's disease patients with azathioprine. Gut. 2003;52:140-142. |

| 29. | Dubinsky MC. Optimizing immunomodulator therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2003;5:506-511. |

| 30. | Winter J, Walker A, Shapiro D, Gaffney D, Spooner RJ, Mills PR. Cost-effectiveness of thiopurine methyltransferase genotype screening in patients about to commence azathioprine therapy for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:593-599. |

| 31. | Dubinsky MC, Reyes E, Ofman J, Chiou CF, Wade S, Sandborn WJ. A cost-effectiveness analysis of alternative disease management strategies in patients with Crohn’s disease treated with azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2239-2247. |