Published online Jun 28, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3003

Revised: May 23, 2009

Accepted: May 30, 2009

Published online: June 28, 2009

AIM: To investigate the 152 cases of paragangliomas resected over the past 32 years in West China Hospital clinicopathologically.

METHODS: All cases of paragangliomas diagnosed at the Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery and Department of Pathology, West China Hospital, China were reviewed. The pathological documents were supplied by the Department of Pathology, West China Hospital, and other necessary data were extracted from the hospital records. The statistical analyses were performed by survival analysis (Kaplan-Meier method), descriptive statistical analyses and χ2 analysis.

RESULTS: The neuroendocrine marker vimentin was found to be selectively expressed in the benign tumors, and there were significant differences in the expression of those markers in both benign and malignant tumors. The survival analysis revealed that survival correlated significantly with the malignancy, metastasis and nodal status.

CONCLUSION: Vimentin may be useful in the differential diagnosis between malignant and benign tumors. The difference in the expression of this marker in the tumors could be a clue to the future clinical diagnosis. The malignancy, metastasis and the nodal status may predict the prognosis of this disease.

- Citation: Feng N, Zhang WY, Wu XT. Clinicopathological analysis of paraganglioma with literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(24): 3003-3008

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i24/3003.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.3003

Paragangliomas (also known as extra-adrenal pheochromocytomas) are rare neuroendocrine neoplasms which are derived from paraganglia, a diffuse neuroendocrine system dispersed from the skull base to the pelvic floor, and these tumors are observed in patients of all ages. Some of the tumors (named as functional paragangliomas) have been discovered to originate, synthesize, store and secrete catecholamines, which leads to elevated levels of urine/serum catecholamines and the typical clinical symptoms such as episodic headache (72%), sweating (69%), and palpitations (51%). The tumors, which can arise in any area of the body containing embryonic neural crest cells, are mainly composed of chromaffin cells[12]. Because of their rarity, little information is available regarding the natural history of these tumors and patient outcome after resection, and especially regarding the diagnosis of malignant tumors. We present a review of 152 cases of resected paragangliomas in our single hospital over a greater than 30-year period and review the relevant literature.

In this study, data were supplied by West China Hospital, Sichuan University (Department of Pathology, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery and other relevant departments). From April 1976 through December 2007, 152 patients with paragangliomas (also referred to as extra-adrenal pheochromocytomas) underwent resection at the West China Hospital, Sichuan University. Demographics, survival time, tumor location, surgical treatment, pathological documents and other relevant data were extracted from hospital records and pathological reports. Patient confidentiality was ensured in all cases.

For the purpose of this study, malignant tumors were defined as those associated with identified lymph node metastases, distant metastases, vascular invasion, tumor necrosis and other identified malignant behaviors. The tumor histology was defined and classified as described in the pathological reports. Mortality and survival was calculated based on last follow-up or death. Statistical analyses included survival analysis (Kaplan-Meier method), descriptive statistical analyses and χ2 analysis. Survival rates were compared using log-rank tests. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

A total of 152 cases of extra-adrenal paraganglioma who underwent resection were identified in West China Hospital, Sichuan University. Amongst these cases were: tumors located in retroperitoneum (85 cases), urinary bladder (6 cases), vertebral canal (7 cases), mediastinum (8 cases), mesostenium (2 cases), lung (3 cases), neck (20 cases, including 8 cases of glomus jugulare tumor, 16 cases of carotid body tumor and 1 case of peri-pharyngeal tumor), and the rest were tumors located in intracalvarium, liver, supraclavicular fossa, vaginal wall, spermatic cord, sacral bone, greater omentum, nasal cavity, mouth floor, rectum and orbital cavity, respectively. The median age of the 152 patients at the diagnosis was 43 years (range; 8-82 years). Eighty-nine patients were men and 64 patients were women. Of these cases, 30 tumors (19.74%) were diagnosed as malignant paragangliomas, including 6 cases of lymph node metastases, 4 cases of distant metastases (3 cases in femur, 1 case in thoracic vertebra), 1 case of recurrence, 22 cases of local invasion (including vascular invasion), and 2 cases were accompanied by other malignant diseases (rectal cancer and neuroblastoma).

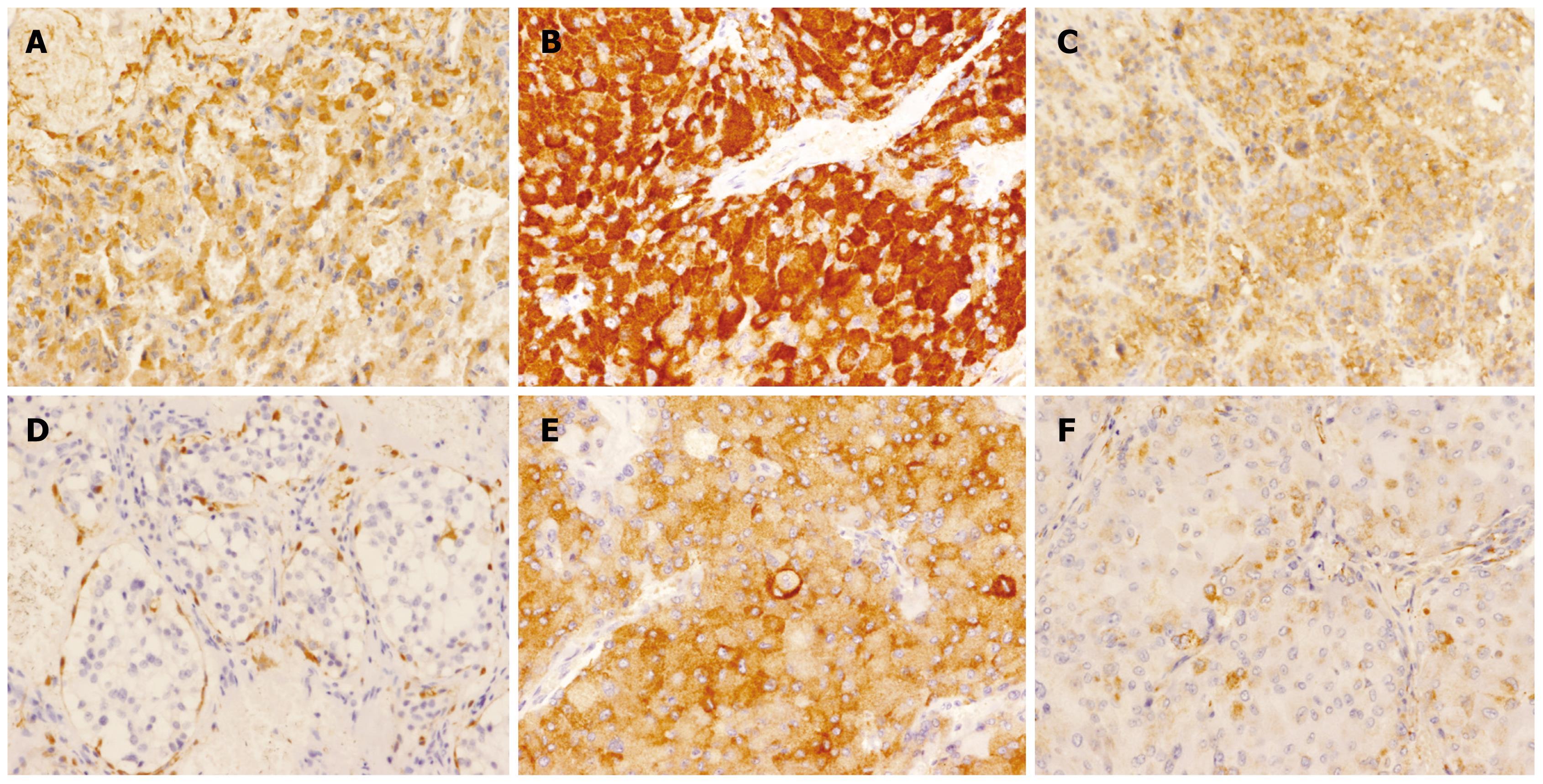

Amongst these 152 cases, paragangliomas from various sites were examined for a host of neural and neuroendocrine markers by immunohistochemistry including neurone specific enolase (NSE), S-100 protein, synaptophysin (Syn), chromogranin A (CgA), Cytokeratin (CK), and vimentin: the results are shown in Table 1. NSE was found to be expressed in nearly all the paragangliomas (benign and malignant), and there was no significant difference between benign or malignant tumors (P = 0.805). S100, Syn and CgA were found to be expressed in most of the paragangliomas; again no significant difference was found between benign or malignant tumors. CK was found to be expressed in some of the cases, but no significant difference was identified between benign or malignant tumors as the P = 0.077. Vimentin was found to be selectively expressed in benign tumors, and a significant difference between benign and malignant paragangliomas was observed (P = 0.007), which may be useful in differentially diagnosing between the malignant and benign tumors. In benign tumors, there was a significant difference in the expression of those markers (P < 0.001), and the same result could also be found in the malignant tumors (P < 0.001). The difference of the expression of those markers in the tumors could be a clue to the future investigation of the diagnosis.

| Markers | Positive rate in benign groups (%) | Positive rate in malignant groups (%) |

| NSE | 99.0 | 100.0 |

| S100 | 84.6 | 71.4 |

| Syn | 85.9 | 95.0 |

| CgA | 92.7 | 88.2 |

| CK | 22.2 | 5.3 |

| Vimentin | 76.9 | 12.5 |

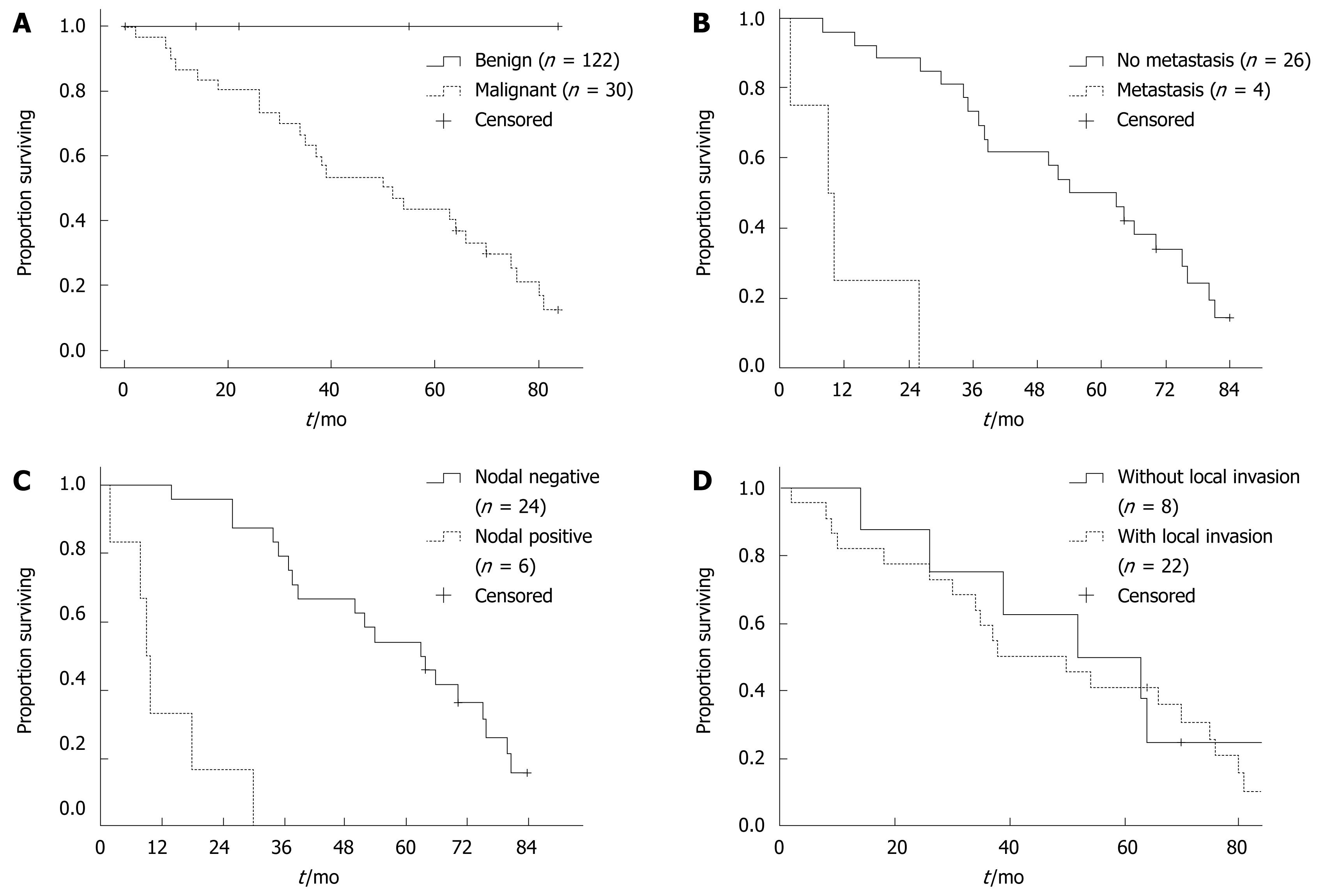

The overall 5-year survival in all the 152 cases was 88.82%, while in the malignant group of 30 cases, the five-year survival was 43.33%. The median survival in malignant cases was 50 mo. It could be observed that survival correlated significantly with malignancy (P < 0.001, Figure 1A). Furthermore, in the malignant group, survival correlated significantly with the presence of metastasis (P < 0.001, Figure 1B), the nodal status (P < 0.001, Figure 1C), but not with the local invasion (P = 0.708, Figure 1D). The survival analysis revealed a significant correlation between survival and the malignancy, metastasis and the nodal status, which may predict the prognosis of this disease.

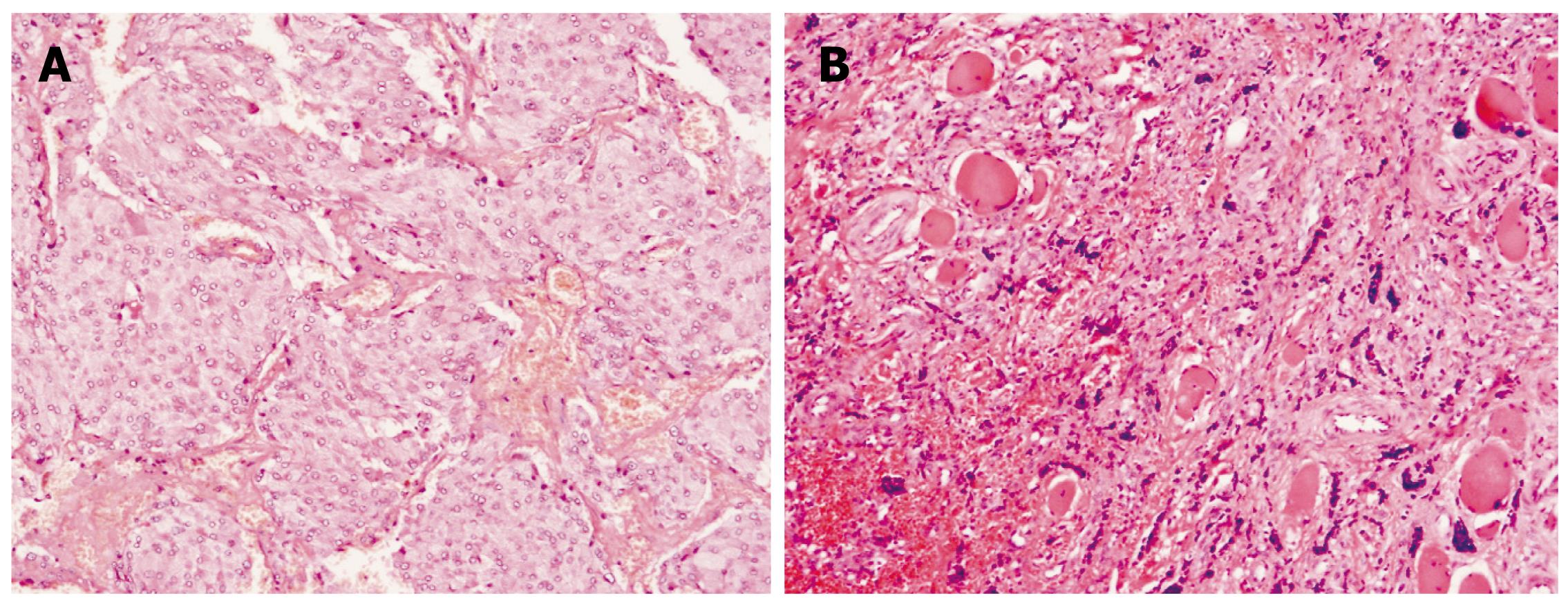

Histologically, paragangliomas are characterized by a honeycomb pattern in which well-circumscribed nests (Zellballen) of round-oval or giant multinucleated neoplastic cells with cytoplasmic catecholamine granules are surrounded by S-100-positive supratentorial cells. Pleomorphism, mitotic figures, and bizarre nuclear forms (which do not necessarily reflect a higher grade of malignancy) may also be seen. There are no standardized histological criteria for differentiating malignant and benign paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas, and they are considered malignant only when cells with neoplastic characteristics are found in areas in which paraganglionic tissue is normally absent. Also, those tumors that contain large numbers of aneuploid or tetraploid cells, as determined by flow cytometry, are more likely to recur[13]. Paragangliomas are of two types, sympathetic and parasympathetic. The tumors usually have their origin in adrenal medulla, the organs of Zuckerkandl, the carotid body, aorticopulmonary, intravagal, etc[45] (Figure 2).

The paraganglioma cells are discovered to be characterized by the presence of neuroendocrine markers, including neurone specific enolase (NSE), S-100 protein, synaptophysin (Syn), chromogranin A (CgA), Cytokeratin (CK), vimentin, PGP9.5 and CD56, etc. The tumor has multiple synthetic activities, and in spite of its heterogeneity, chromogranin A and synaptophysin are the most common neuropeptides synthesised, as they are associated with the presence of neuroendocrine storage granules[6]. The presence of some of these markers in the paragangliomas, as well as their differential expression between the benign and malignant tumors, has been confirmed in our study which may suggest that an immunophenotypic analysis could be useful in the diagnosis of this disease (Figure 3).

Paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas are embryologically related tumors, sharing a neural-crest origin, several clinical features, and an overlapping genetic profile, although they do show variability as to site, histology, and biology. The occurrence of these tumors in familial settings, their association with hereditary syndromes, and their genetic alterations revealed that some cases are familial[78]. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN2), neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) and von Hippel Lindau (VHL) syndrome subtypes 2A, 2B, and 2C account for about 10% of cases; the genes involved being the RET proto-oncogene and the NF1 and VHL tumor suppressor genes, respectively. However, with the identification of the familial paraganglioma syndromes, characterized by mutations in the subunits of the succinic dehydrogenase (SDH) enzyme (Table 2, Note: The syndromes were named in the order in which they were identified)[8], it now appears that over 30% of cases are associated with an inherited genetic disposition[8–10]. In our investigation, a very high malignancy rate of 19.74% was obtained, which may suggest that a significant proportion of these patients may have underlying familial SDH gene mutations. This finding also urges us bear in mind the gene mutation test for paraganglioma cases in following investigations. In many previous studies, it has been found that some malignant paraganglioma showed both loss of 8p and gain of 11q13, suggesting these alterations could be markers of malignancy. Furthermore, it has been confirmed that mutations of the SDH and loss of heterozygosity (LOH) on chromosome 11 result in a small fraction of sporadic and almost all familial forms of paraganglioma. The development of paraganglioma in diverse anatomical locations in subjects with SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD germline mutations indicates that the paraganglionic system throughout the body is a target for paraganglioma. Thus, the possibility of mitochondrial SDH germline mutations should be raised in the differential diagnosis of all paragangliomas. Whether certain subunit mutations are more strongly associated with a given anatomical location, hormonal activity, malignancy, age at onset, tumor multiplicity, and tumor size remains to be established. Hereditary paraganglioma is closely tied in with germline mutations affecting genes encoding for the SDH enzyme system, which is a heterotetrameric complex with functions in the Krebs cycle related to the oxidation of succinate to fumarate leading to ATP production. The catalytic subunits of SDH are encoded by the genes SDHD, SDHB, SDHC, and SDHA. SDHD encodes the smallest subunit of SDH. SDHA and SDHB are anchored to the mitochondrial inner membrane through membrane-spanning subunits encoded by SDHC and SDHD. A large number of mutations (approx 30) in hereditary paraganglioma have been described for SDHD and SDHB each[31112]. Germline mutations in SDH genes are associated with the development of paraganglioma in diverse anatomical locations, a finding that has important implications for the clinical management of patients and genetic counseling of families. Consequently, patients with paraganglioma and a SDH germline mutation should be diagnosed as potentially hereditary, regardless of family history, anatomical location, or multiplicity of tumors.

| Adrenal | Extra-adrenal Sympathetic | Parasympathetic | ||

| Familial paraganglioma 1 | SDHD | + | + | + |

| Familial paraganglioma 3 | SDHC | + | ||

| Familial paraganglioma 4 | SDHB | + | + | + |

In the past, studies involving biochemical measurements of urine/plasma catecholamines were found to have appropriate sensitivity and specificity for detecting catecholamine-secreting functional paragangliomas. Among all the tests studied, measurements of plasma free metanephrines were found to have the best predictive value for excluding or confirming a pheochromocytoma or functional paraganglioma[1314]. As for those nonfunctional paragangliomas, because they are a heterogeneous group of tumors, using a single test may not be reliable, and a combination of tests may result in higher diagnostic accuracy. Furthermore, scintigraphy with iodide 131-labeled metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG 131) is found to be useful, not only for noninvasive diagnosis of paragangliomas, but also for palliative treatment in cases for which other types of treatment have been unsuccessful[15]. Positron emission tomography (PET)-scanning with [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose, [11C]-hydroxyephedrine, or 6-[18F] fluorodopamine may help to identify conventionally undetectable tumors[16–19]. For the diagnosis of malignancy in paraganglioma, the clinical and histological features predictive of malignancy are still poorly defined for this type of tumor; the level of serum catecholamines does not necessarily correlate with the malignancy of the tumor. In most previous literature, immunohistochemistry has not been of use for refining the diagnosis of malignant potential, though some malignant tumors may express fewer or different peptides than benign. S100-positive sustentacular cells are often sparse in malignant tumors, although this test is not 100% sensitive[3620]. The only absolute criterion for malignancy is the presence of metastases to sites where chromaffin tissue is not usually found. However, some other features of the tumor may indicate the malignant characteristic, including recurrence, gross local invasion, vascular or capsular invasion, tumor necrosis, malignant histological pattern and cellularity[21]. Also, some evidence suggests that multifactorial scoring systems can help to histopathologically discriminate tumors which pose a significant risk of metastasis from those that do not. In 2002, Thompson[22] proposed the PASS system (Pheochromocytoma of Adrenal Scaled Score), which scores multiple microscopic findings (Table 3). A PASS of < 4 accurately identified all histologically benign and clinically benign tumors. A PASS of ≥ 4 correctly identified all tumors that were histologically malignant. In our study, vimentin was found to be selectively expressed in benign tumors, which may be useful in the differential diagnosis between the malignant and benign tumors. However, in the PASS system as Thompson[22] proposed, vimentin has not been involved and scored as a neuroendocrine marker in the diagnosis of this disease. In order to confirm the value of vimentin, following investigations should involve more cases and areas, more precise testing techniques such as the quantitation test of RNA and protein should be involved, as well. If the diagnostic value of vimentin could be confirmed in the future, vimentin should indisputably be added into the PASS system.

| Feature | Score if present (No. of points assigned) |

| Large nests or diffuse growth (> 10% of tumor volume) | 2 |

| Central (middle of large nests) or confluent tumor necrosis (not degenerative change) | 2 |

| High cellularity | 2 |

| Cellular monotony | 2 |

| Tumor cell spindling (even if focal) | 2 |

| Mitotic figures > 3/10 HPF | 2 |

| Atypical mitotic figure(s) | 2 |

| Extension into adipose tissue | 2 |

| Vascular invasion | 1 |

| Capsular invasion | 1 |

| Profound nuclear pleomorphism | 1 |

| Nuclear hyperchromasia | 1 |

| Total | 20 |

Due to the rarity of this disease, the outcomes of survival analysis in different research studies are not highly coherent. In benign cases, most studies showed that the 5-year survival rate is above 95%; recurrences occur in less than 10% of cases. Whereas, due to the lower incidence of malignant paragangliomas, there are single case reports rather than larger scale case studies and clinical controlled randomized tests, and the exact survival in the malignant cases is difficult to approach. Similar to our study, the value has been found to be 43.33%. The survival in malignant cases was thought to be related to the familial circumstance, the stage of the disease at the diagnosis, the therapeutic methods and follow-up after the surgery, which has also been identified by our study[2324]. In our study, it was also confirmed that the survival in malignant cases was obviously lower than the benign group as previously reported in many articles. Furthermore, it was revealed that the non-chromaffin site metastases and nodal metastases distinct from local invasion played an important role in the progression and prognosis of this disease, which may help in the estimation of survival in each case and moreover offer individualized therapy for each patient. This result also means that following studies should investigate the possible unique mechanism of metastasis and nodal invasion of this disease, so that the method to prevent this progress may be found.

Paraganglioma is a rare neuroendocrine neoplasm. This disease usually originates from a diffuse neuroendocrine system dispersed from the skull base to the pelvic floor. Paraganglioma is observed in patients of all ages. Some of the tumors (named as functional paragangliomas) have been discovered to originate, synthesize, store and secrete catecholamines, which leads to elevated levels of urine/serum catecholamines and the typical clinical symptoms such as episodic headache (72%), sweating (69%), and palpitations (51%). Due to the rarity of this disease, the natural history of these tumors, patient outcome after resection, and especially the diagnosis of malignant tumors are still under investigation.

Nowadays, there are no standardized histological criteria for differentiating malignant and benign paragangliomas, and they are considered malignant only when cells with neoplastic characteristics are found in areas in which paraganglionic tissue is normally absent. The paraganglioma cells are discovered to be characterized by the presence of neuroendocrine markers, including neurone specific enolase (NSE), S-100 protein, synaptophysin (Syn), chromogranin A (CgA), Cytokeratin (CK), vimentin, PGP9.5 and CD56, etc. The differential expression of those markers between the benign and malignant tumors and the value of them in the differential diagnosis are broadly discussed.

A Pheochromocytoma of Adrenal Scaled Score (PASS) system was proposed for making the differential diagnosis between malignant cases and benign cases. This system scores multiple microscopic findings such as tumor necrosis, high cellularity, cellular monotony, vascular invasion, etc. The differential expression of some markers between the benign and malignant tumors has been confirmed in many studies, which may suggest that immunophenotypic analysis could be useful in the diagnosis of this disease.

In the study, vimentin was found to be selectively expressed in benign tumors, which may be useful in the differential diagnosis between the malignant and benign tumors. The high malignancy rate of 19.74% may suggest that a significant proportion of these patients have underlying familial SDH gene mutations. This finding may also attract more attention to the gene mutation test for paraganglioma cases in following investigations. The survival data may help clinicians to estimate the survival in each case and moreover offer individualized therapy for each patient.

Paraganglioma (also known as extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma) is a rare neuroendocrine neoplasm which is derived from paraganglia, a diffuse neuroendocrine system dispersed from the skull base to the pelvic floor. Vimentin is a member of the intermediate filament family of proteins. Intermediate filaments are an important structural feature of eukaryotic cells. They, along with microtubules and actin microfilaments, make up the cytoskeleton. Although most intermediate filaments are stable structures, in fibroblasts, vimentin exists as a dynamic structure.

This manuscript provides relevant data on the rare condition of paraganglioma, especially in the west region of China, which has significant usefulness for clinicians and pathologists alike. The finding about the differential expression of vimentin may be important in the diagnosis of this disease. The survival analysis may help the clinicians to make clinical decisions.

| 1. | Antonello M, Piazza M, Menegolo M, Opocher G, Deriu GP, Grego F. Role of the genetic study in the management of carotid body tumor in paraganglioma syndrome. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;36:517-519. |

| 2. | Yeo H, Roman S. Pheochromocytoma and functional paraganglioma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2005;17:13-18. |

| 3. | Tischler AS. Pheochromocytoma and extra-adrenal paraganglioma: updates. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1272-1284. |

| 4. | Lee JA, Duh QY. Sporadic paraganglioma. World J Surg. 2008;32:683-687. |

| 5. | Havekes B, van der Klaauw AA, Hoftijzer HC, Jansen JC, van der Mey AG, Vriends AH, Smit JW, Romijn JA, Corssmit EP. Reduced quality of life in patients with head-and-neck paragangliomas. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;158:247-253. |

| 6. | Erickson LA, Lloyd RV. Practical markers used in the diagnosis of endocrine tumors. Adv Anat Pathol. 2004;11:175-189. |

| 7. | Walther MM, Reiter R, Keiser HR, Choyke PL, Venzon D, Hurley K, Gnarra JR, Reynolds JC, Glenn GM, Zbar B. Clinical and genetic characterization of pheochromocytoma in von Hippel-Lindau families: comparison with sporadic pheochromocytoma gives insight into natural history of pheochromocytoma. J Urol. 1999;162:659-664. |

| 8. | Bertherat J, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. New insights in the genetics of adrenocortical tumors, pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Horm Metab Res. 2005;37:384-390. |

| 9. | Fakhry N, Niccoli-Sire P, Barlier-Seti A, Giorgi R, Giovanni A, Zanaret M. Cervical paragangliomas: is SDH genetic analysis systematically required? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;265:557-563. |

| 10. | Baysal BE. Genomic imprinting and environment in hereditary paraganglioma. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2004;129C:85-90. |

| 11. | Baysal BE. Hereditary paraganglioma targets diverse paraganglia. J Med Genet. 2002;39:617-622. |

| 12. | Sandberg AA, Stone JF. The genetics and molecular biology of neural tumors. Humana Press: New York 2008; 172-180. |

| 13. | Eisenhofer G, Goldstein DS, Walther MM, Friberg P, Lenders JW, Keiser HR, Pacak K. Biochemical diagnosis of pheochromocytoma: how to distinguish true- from false-positive test results. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:2656-2666. |

| 14. | Lenders JW, Pacak K, Walther MM, Linehan WM, Mannelli M, Friberg P, Keiser HR, Goldstein DS, Eisenhofer G. Biochemical diagnosis of pheochromocytoma: which test is best? JAMA. 2002;287:1427-1434. |

| 15. | Furuta N, Kiyota H, Yoshigoe F, Hasegawa N, Ohishi Y. Diagnosis of pheochromocytoma using [123I]-compared with [131I]-metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy. Int J Urol. 1999;6:119-124. |

| 16. | Pacak K, Eisenhofer G, Goldstein DS. Functional imaging of endocrine tumors: role of positron emission tomography. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:568-580. |

| 17. | Ilias I, Pacak K. Anatomical and functional imaging of metastatic pheochromocytoma. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1018:495-504. |

| 18. | Ilias I, Yu J, Carrasquillo JA, Chen CC, Eisenhofer G, Whatley M, McElroy B, Pacak K. Superiority of 6-[18F]-fluorodopamine positron emission tomography versus [131I]-metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy in the localization of metastatic pheochromocytoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4083-4087. |

| 19. | Ilias I, Pacak K. Current approaches and recommended algorithm for the diagnostic localization of pheochromocytoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:479-491. |

| 20. | Kuroda N, Tamura M, Ohara M, Hirouchi T, Mizuno K, Miyazaki E, Hayashi Y, Lee GH. Possible identification of third stromal component in extraadrenal paraganglioma: myofibroblast in fibrous band and capsule. Med Mol Morphol. 2008;41:59-61. |

| 21. | August C, August K, Schroeder S, Bahn H, Hinze R, Baba HA, Kersting C, Buerger H. CGH and CD 44/MIB-1 immunohistochemistry are helpful to distinguish metastasized from nonmetastasized sporadic pheochromocytomas. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:1119-1128. |

| 22. | Thompson LD. Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal gland Scaled Score (PASS) to separate benign from malignant neoplasms: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 100 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:551-566. |