CASE REPORT

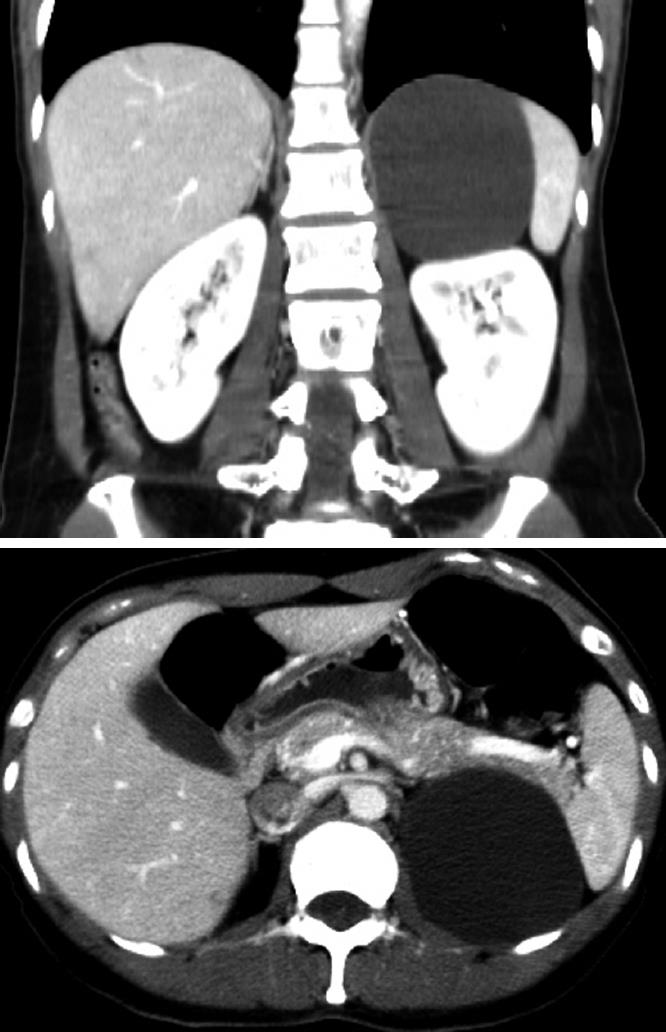

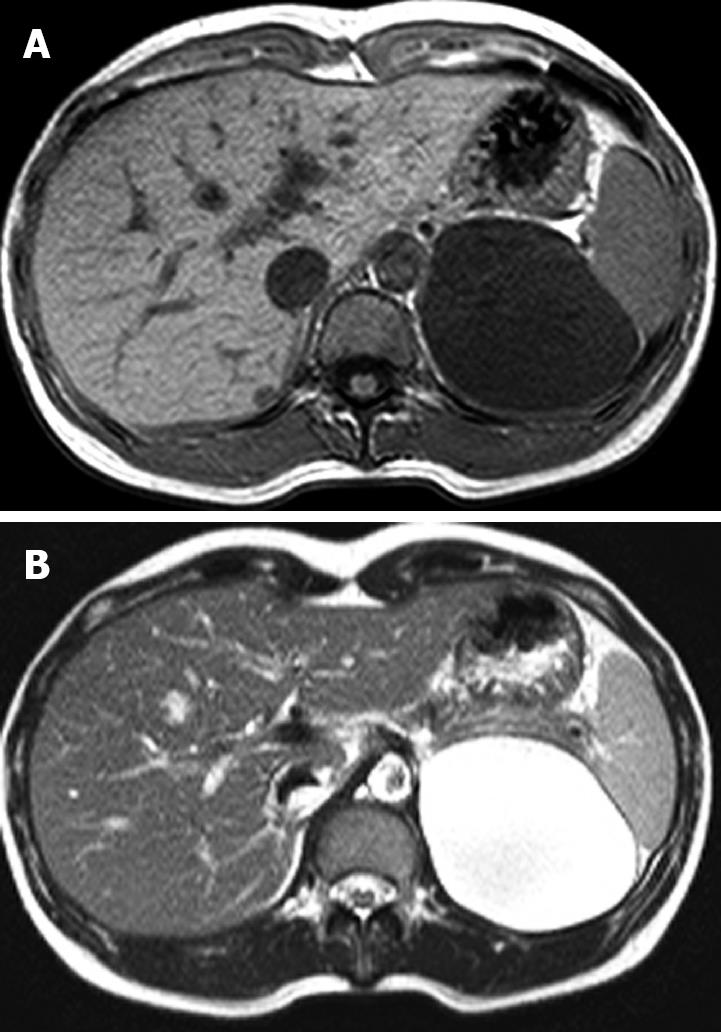

A 38-year-old woman was admitted to our service with a two-year history of abdominal discomfort, anorexia, and nausea. She had no history of trauma and had undergone a laparoscopic unilateral salpingoophorectomy. A physical examination revealed no palpable abdominal masses and no tenderness in the abdomen. Routine laboratory tests were within normal limits. An abdominal computed tomography scan showed a 9 cm well-defined cystic lesion displacing the left kidney (Figure 1). The cystic lesion appeared to arise from the retroperitoneum. For further evaluation of the cystic lesion, magnetic resonance imaging was carried out and the cystic lesion showed low signal intensity on the T1-weighted image and high signal intensity on the T2-weighted image (Figure 2). There were no findings of suspected malignancy on the radiological image. We decided to perform a laparoscopic resection of the cystic lesion to relieve long-lasting gastrointestinal symptoms and to diagnose the lesion.

Figure 1 An abdominal computed tomography scan showing a 9 cm well-defined cystic lesion, which abuts the spleen, kidney and pancreas tail.

Figure 2 Magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen.

A low signal intensity cystic mass on the T1-weighted image (A) and a high signal intensity cystic mass on the T2-weighted image (B).

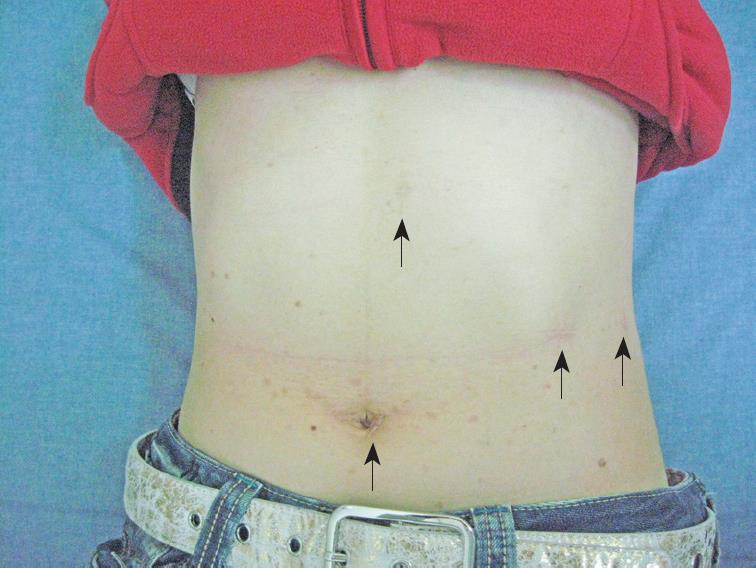

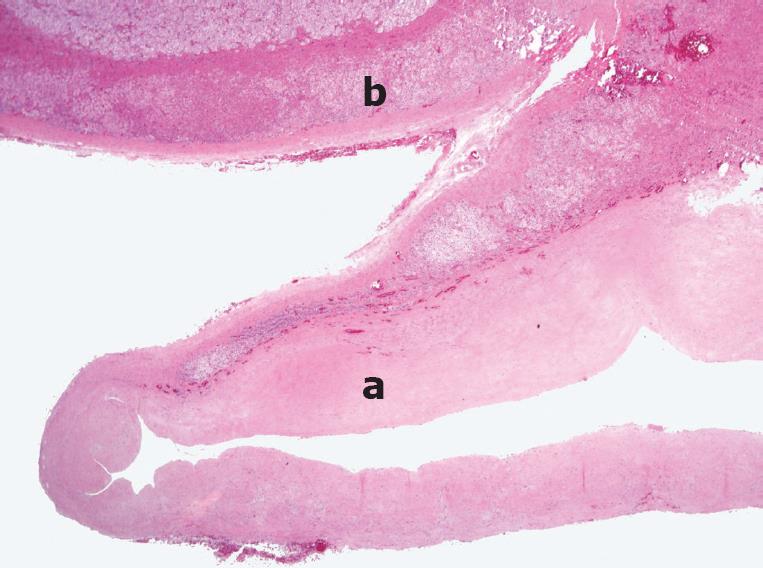

The patient was placed in the right lateral decubitus, flexed at the waist. A 12-mm trocar was inserted in the umbilical region via an open incision. Three other operating ports were placed along the left costal margin, as shown in Figure 3. The second 10-mm trocar was introduced on the anterior axillary line. The third 5-mm trocar was introduced on left side of the second trocar and placed under the costal margin. The fourth 5-mm trocar was introduced in the posterior axillary line and was used for a retractor. The splenic flexure of the colon was mobilized from the left paracolic gutter to the inferior pole of the spleen. The splenorenal ligament was divided to allow the spleen and tail of the pancreas to rotate medially, exposing the left retroperitoneum. At that time, a smooth, well-capsulated cystic mass, measuring 9 cm × 8 cm × 8 cm, arising from the left adrenal gland was found. The superior, medial and lateral border of the lesion was first dissected from neighboring tissue with a LigaSure (Valley Lab, Boulder, CO). The dissection proceeded inferiorly to expose and ligate the left adrenal vein. The adrenal vein was identified and divided with a 2.5-mm endoscopic vascular stapler (Ethicon). The adrenal cystic lesion, completely freed, was placed in a surgical bag (Endocatch; Ethicon). The cystic contents were aspirated with a needle and were a thin, yellowish fluid. The specimen was extracted via the 10-mm port side by enlarging the incision from 1 to 2.5 cm. The operative time was 110 min and the blood loss was 50 mL. Gross appearance showed a thin-walled, yellowish, 6 cm × 3 cm × 3 cm unilocular adrenal lesion (Figure 4). Histological examination showed an adrenal pseudocyst without an epithelial or endothelial lining (Figure 5). The patient had no postoperative complications and she was discharged four days after surgery. The abdominal pain and gastrointestinal symptoms resolved after surgery.

Figure 3 Placement of the laparoscopic trocar and operative ports.

A 12-mm trocar was placed in the periumbilical region, and three other operating ports were placed in the abdomen (arrows). The photograph was taken eight months after surgery.

Figure 4 Gross appearance of the 6 cm × 3 cm × 3 cm adrenal cystic lesions.

The cystic lesion adheres to adrenal gland tissue.

Figure 5 Histopathology showing an adrenal pseudocyst (a) and adrenal tissue remnants on the upper aspect (b).

The cyst wall is composed of a thick layer of hyalinized connective tissue without an epithelial or endothelial lining (a). HE staining (Original magnification, × 40).

DISCUSSION

Adrenal cysts are classified as a cystic degeneration of adrenal neoplasms, true cysts, pseudocysts, and infectious cysts[1–3]. Among adrenal cysts, the most common types are epithelial cysts and pseudocysts. True cysts are lined with endothelial or mesothelial cells[4]; however, adrenal pseudocysts are devoid of an epithelial or endothelial lining, arise within the adrenal gland, and are surrounded by a fibrous tissue wall. Infectious cysts are most commonly caused by Echinococcus[5].

Adrenal pseudocysts are rare and account for 32% to 80% of all adrenal cysts[36–9]. Adrenal pseudocysts are often found incidentally on imaging studies or at the time of autopsy. The majority of adrenal pseudocysts are found because of their size-related symptoms[6–8]. Symptoms include gastrointestinal disturbance, early satiety, and a palpable abdominal mass. Patients can present with acute abdominal findings if intracystic hemorrhage or rupture occurs[10].

The etiology of adrenal pseudocysts is unknown; however, several mechanisms have been proposed to account for their occurrence, including cystic degeneration of a primary adrenal neoplasm, degeneration of a vascular neoplasm, and malformation and hemorrhage of adrenal veins into the adrenal gland[1–36711]. The etiology of our patient’s pseudocyst was indeterminate.

Due to the wide use of the diagnostic imaging modalities, the detection rate of adrenal cystic lesions is increasing. However, preoperative confirmatory diagnosis of a large adrenal cyst can be very difficult, because of the indistinct boundary with surrounding organs and adhesion to neighboring organs[12].

The differential diagnosis of adrenal pseudocysts includes splenic, hepatic, and renal cysts, as well as mesenteric or retroperitoneal cysts, urachal cysts, and solid adrenal tumors[1213]. Adrenal pseudocysts must be differentiated from other benign or malignant lesions originating from the adrenal gland or the kidney unilaterally[14–17]. In addition, an exact diagnosis is clinically important because an adrenal cyst > 6 cm carries an increased risk of adrenal malignancy. The reported incidence of malignancy in adrenal cystic lesions is approximately 7%[1819].

Typically, radiological findings of adrenal cysts reveal thin walls filled with watery fluid and occasional calcifications[2021]. Often, the inferior wall of the cyst is concave or flat, conforming to the shape of the upper pole of the renal contour.

On computed tomography scan, the present cyst could not be differentiated from a renal or adrenal lesion. The CT scan was not definitive, therefore an MRI was obtained. The adrenal gland was not visualized by the MRI scan and the cystic mass was thus considered to be of pancreatic rather than adrenal origin. The cystic mass could not be differentiated from a retroperitoneal mucinous cystic neoplasm. We chose the laparoscopic approach because of the time involved, the anticipated minimal blood loss, the acceptable rate of complications, and the excellent postoperative quality of life. There are few reports of a case of retroperitoneal mucinous cystadenomas treated by laparoscopic surgery[22–24].

During the laparoscopic procedure, we found that the cystic mass had arisen from the left adrenal gland, not the pancreas. We believed that this cystic mass was an adrenal cyst and removed it completely by laparoscopic surgery.

The choice of treatment for adrenal pseudocysts depends on several factors, including endocrine function, symptoms, size, and correct differentiation from an adrenal cyst.

Surgical excision is indicated in the presence of symptoms, suspicion of malignancy, an increase in size, the occurrence of complications, or detection of a functioning adrenal cyst, and can be managed by open surgery or a laparoscopic approach[1225–27]. Kalady et al[28] recommended that adrenal cysts > 6 cm should be approached using an open procedure because of concerns about potential malignancy. In the case of giant pseudocysts, most authors prefer an open adrenalectomy, because the laparoscopic approach is not sufficient to control such large masses with active internal bleeding[29]. However, several reports demonstrate that laparoscopic adrenalectomy for large (> 6 cm) adrenal lesions is surgically feasible and can be applied for any adrenal disease, including benign and potentially malignant lesions[2530–32].

This case was sufficiently instructive to point out that adrenal cystic lesions can be radiologically mistaken for renal cysts or cystic neoplasms.

This is a rare report of an adrenal pseudocyst mimicking a retroperitoneal mucinous cystic neoplasm, which was treated by laparoscopic resection. Although adrenal pseudocysts might be misdiagnosed as retroperitoneal mucinous cystic neoplasms, a laparoscopic approach to cystic lesions in the suprarenal area should be the initial choice.