Published online Jun 21, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2918

Revised: May 15, 2009

Accepted: May 22, 2009

Published online: June 21, 2009

We present a case of a transsexual patient who underwent a partial pelvectomy and genital reconstruction for anal cancer after chemoradiation. This is the first case in literature reporting on the occurrence of anal cancer after male-to-female sex reassignment surgery. We describe the surgical approach presenting our technique to avoid postoperative complications and preserve the sexual reassignment.

- Citation: Caricato M, Ausania F, Marangi GF, Cipollone I, Flammia G, Persichetti P, Trodella L, Coppola R. Surgical treatment of locally advanced anal cancer after male-to-female sex reassignment surgery. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(23): 2918-2919

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i23/2918.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.2918

Pelvic surgery after male to female sex reassignment implies a particular surgical approach: firstly, anatomic variations during resection can be considerable; secondly, although genital reconstruction is an essential target for patients, it is a difficult operation especially after chemoradiation. We present a case of a transsexual patient who underwent a partial pelvectomy and genital reconstruction for anal cancer.

A 63 year-old patient presented with rectal bleeding and anal pain. In 1982, she was submitted to male-to-female sex reassignment surgery according to the technique described by Meyer et al[1] consisting of penile disassembly followed by vaginoplasty using all penile components except the corpora cavernosa.

Physical examination on January 2006 revealed an anal ulcer and a biopsy showed evidence of a squamous carcinoma. Clinical staging at diagnosis indicated an involvement of the inguinal lymph nodes (T2N2M0, stage III B anal cancer[2]).

Concurrent chemoradiation was administered according to the following scheme: the radiation field included the primary tumour and inguinal lymph nodes; a total of 45 Gy in 25 fractions was administered at the primary tumour and a total of 30.6 Gy at the inguinal fields. Each chemotherapy cycle lasted 38 d and consisted of oxaliplatin 180 mg/m² on days 1, 19 and 38 and xeloda 1300 mg/m² concurrently to radiotherapy. A radiotherapy boost was also administered either on the primary tumour or the inguinal lymph nodes.

Clinical evaluation six weeks after the completion of chemoradiation showed a complete clinical response. At one year follow-up, CT scan showed local recurrence involving the anal sphincter, neo-vagina and bladder neck. A surgical approach was planned in collaboration with reconstructive surgery in order to preserve sex reassignment.

The surgical approach consisted of two parts. During the abdominal portion of the procedure, the rectum was mobilized, and the posterior bladder wall and the seminal vesicles were exposed. During the pelvic portion of the procedure the excision was completed. The perineal skin incision included the neo-vagina and urethra. The rectum and the anus were removed en bloc with the bladder neck, neo-vagina, seminal vesicles and prostate. The bladder neck was sutured, and sovrapubic cystostomy and the colostomy were performed.

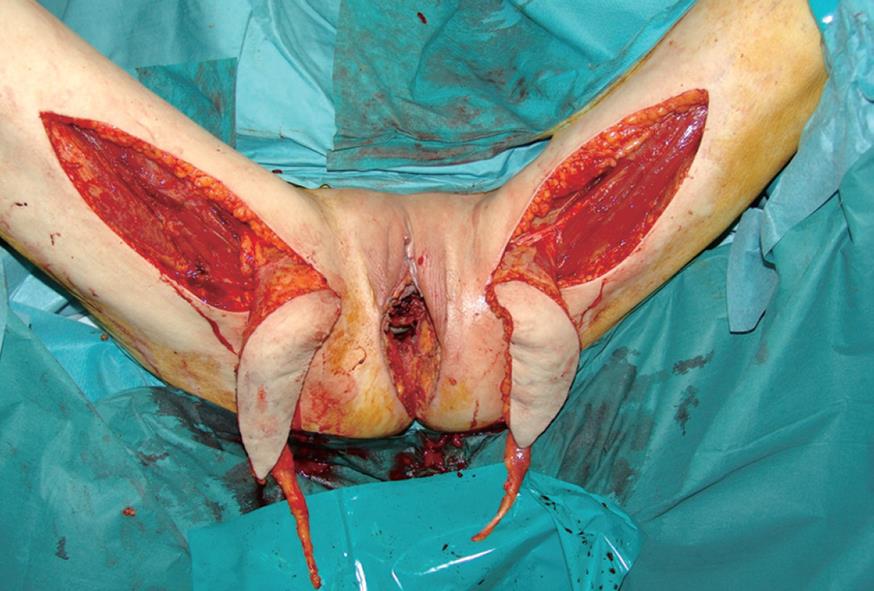

Following the excision, a loss of substance of 20 cm × 15 cm resulted. An elliptical skin island up to 15 cm × 6 cm was outlined over the proximal two-thirds of the gracilis muscle of each thigh, according to a technique previously described by our group[3] (Figure 1). The anterior margin of the incision lay on a line drawn between the pubic tubercle and the semitendinosus tendon. The gracilis tendon was identified distally, and the tendinosus insertion divided. The posterior incision was made down to the muscle. The flap was then elevated from distal to proximal on the thigh. The vascular supply of the flap was the medial femoral circumflex artery, which enters the gracilis muscle 7-10 cm below the pubic tubercle. Once the pedicle was identified and preserved, the proximal muscle was dissected. The entire myocutaneous flap was tunnelled through the subcutaneous skin bridge into the vaginal defect and exteriorized through the introitus. The bilateral flaps were sutured to each other at the midline. The neovagina was shaped into a pouch and then inserted into the pelvic space that left after the exenteration. The proximal end of the neovagina was sutured to the introitus. The result after one month is presented in Figure 2.

The postoperative course was complicated by the occurrence of urinary leak, successfully treated with bilateral temporary nephrostomy.

The histology confirmed a locally advanced squamous carcinoma of the anus. Surgical margins were involved. The patient is free of disease at 8 mo follow-up.

This is the first case in literature reporting on the occurrence of anal cancer after male-to-female sex reassignment surgery. We tried to achieve two important targets: (1) to avoid postoperative complications of extended surgery after chemoradiation. In fact, perineal reconstruction with gracilis muscle flaps proved very useful in preventing the primary postactinic healing delay. Immediate perineal reconstruction is helpful in avoiding delayed complications due to radiotherapy, namely tissue sclerosis and irreversible damage to irradiated tissues. Gracilis flap transposition ensures a persistent vascular contribution to the irradiated perineal tissues, increasing local oxygenation and leading to more rapid recovery of the surgical wound. In addition to the vascular advantages, the gracilis muscular flap, fixed to the pelvic floor, prevents dead spaces and thus reduces the incidence of seromas. Extended perineal surgery can subvert the architecture of the pelvic floor reducing the sustaining forces and leading to herniation into the perineal space. We would like to point out that the muscular gracilis flap is crucial to compensate for the lack of perineal support after this operation. Once the defect is closed, no further procedure is needed to treat the above mentioned complications in unreconstructed patients, allowing patients to recover quickly and possibly receive adjuvant therapies. (2) to reconstruct the sexual reassignment. This point may not be essential for the surgeon who often assumes that radical surgery is the only target of the operation, but it remains an important issue for patients.

In conclusion, this is the first case in literature reporting on surgical treatment of locally advanced anal cancer after male-to-female sex reassignment surgery. Surgical reconstruction is a reasonable and helpful option to avoid severe complications and preserve sexual reassignment.

| 1. | Meyer R, Kesselring UK. One-stage reconstruction of the vagina with penile skin as an island flap in male transsexuals. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1980;66:401-406. |

| 2. | Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, Fritz AG, Balch CM, editors . AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook. 6th ed. New York: Springer-Verlag 2002; . |

| 3. | Persichetti P, Cogliandro A, Marangi GF, Simone P, Ripetti V, Vitelli CE, Coppola R. Pelvic and perineal reconstruction following abdominoperineal resection: the role of gracilis flap. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;59:168-172. |