Published online Jun 21, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2882

Revised: May 11, 2009

Accepted: May 18, 2009

Published online: June 21, 2009

AIM: To identify risk factors to help predict which patients are likely to fail to appear for an endoscopic procedure.

METHODS: This was a retrospective, chart review, cohort study in a Canadian, tertiary care, academic, hospital-based endoscopy clinic. Patients included were: those undergoing esophagogastroduodenoscopy, colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy and patients who failed to appear were compared to a control group. The main outcome measure was a multivariate analysis of factors associated with truancy from scheduled endoscopic procedures. Factors analyzed included gender, age, waiting time, type of procedure, referring physician, distance to hospital, first or subsequent endoscopic procedure or encounter with gastroenterologist, and urgency of the procedure.

RESULTS: Two hundred and thirty-four patients did not show up for their scheduled appointment. Compared to a control group, factors statistically significantly associated with truancy in the multivariate analysis were: non-urgent vs urgent procedure (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.06, 2.450), referred by a specialist vs a family doctor (OR 2.76, 95% CI 1.31, 5.52) and office-based consult prior to endoscopy vs consult and endoscopic procedure during the same appointment (OR 2.24, 95% CI 1.33, 3.78).

CONCLUSION: Identifying patients who are not scheduled for same-day consult and endoscopy, those referred by a specialist, and those with non-urgent referrals may help reduce patient truancy.

- Citation: Wong VK, Zhang HB, Enns R. Factors associated with patient absenteeism for scheduled endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(23): 2882-2886

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i23/2882.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.2882

Patient absenteeism from scheduled outpatient appointments is a major problem for all ambulatory clinics. Failure to attend an appointment results in inefficiency because the vacant appointment interval is often not used by another patient. This typically results in ongoing expenditures without concomitant reimbursement thereby decreasing appropriate resource utilization. This is particularly important for endoscopic procedures where a specific interval is scheduled and appropriate preparation is required for each patient. If a patient does not attend the prearranged endoscopy time, often the time is simply absorbed into the rest of the day without an appropriate substitute being found.

There are a number of maneuvers that various clinics have used in an attempt to decrease truancy from endoscopic appointments. Some sites notify all patients within a few days of their scheduled time, others will insist that the patient themselves confirm their appointment, other sites even “over-book” the endoscopy unit to account for a small percentage that will not appear on their scheduled day. Various methods such as telephone[1] or text message[2] reminders and mailed pre-procedural pamphlets[3] have been used successfully to decrease truancy from endoscopic appointments. Very little research has been devoted to enhancing our understanding of why patients do not appear at their scheduled appointments, and that which has been done has demonstrated conflicting results[4–8].

Research based in adolescent outpatient clinics have found that telephone reminders the day before the scheduled appointment help to reduce “no-show” rates[9]. Other studies have shown that such reminder systems do not improve patient attendance rates[1011]. One prospective study found that previous non-attendance for an outpatient appointment was the strongest predictor of future non-attendance behavior[8]. There has been limited research into the explanations or reasons for patient absenteeism for scheduled gastroenterology appointments[12]. If patients could be identified as “high-risk” for absenteeism, then specific targeted efforts could be developed to ensure their appropriate appearance at their procedure. The objective of this study is to identify risk factors that may help predict which patients are the most likely to be truant for a scheduled elective endoscopic procedure.

This study involved all consecutive patients scheduled to undergo an elective esophagoduodenoscopy (EGD), flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy in a single Canadian tertiary care, gastroenterology clinic (hospital based) in the year 2003. A retrospective chart review was performed to identify all patients who did not appear for their scheduled outpatient endoscopic procedure and they were compared to a control group (randomly selected patients from the same time period who did show at their appointment) to generate predictors of patient absenteeism. It was felt that it was unnecessary, and in fact not practical, to assess all patients during the entire year that did appear for their examination. By using a random sample (selected from a similar time period as the truant group) comparison between the two groups was deemed statistically appropriate. Patients referred from other hospitals and those undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) were excluded.

The factors analyzed included gender, age, duration of time on a waiting list, time of day of procedure (07:30-10:00, 10:00-12:30, 12:30-15:00), day of the week, type of procedure, referring physician (family physician vs other specialist), distance to hospital (divided into regional areas), whether the patient went direct to the endoscopy suite for a consult and endoscopy during the same appointment without consulting the gastroenterologist in his/her outpatient clinic prior to the procedure, urgency of the procedure (urgent procedures were defined as patients who were bleeding or who had radiological abnormalities warranting an endoscopic procedure) and whether the patient was undergoing a repeat procedure by the previous gastroenterologist or surgeon. Univariate analysis was then performed to determine independent associations of each factor to patient “no-shows”. Odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence interval (95% CI) and their respective P-values were generated. Following this, multivariate analysis was performed using logistic regression analysis. Only factors that were statistically significant in multivariate analysis were reported in the model. The SPSS software package for Windows (Release 15.0.0-6 Sept 2006; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Ethics approval was obtained through St Paul’s Hospital, University of British Columbia to conduct the study.

Table 1 shows the prevalence of patient characteristics that were analyzed as potential predictive factors for truancy for scheduled endoscopic procedure. The absenteeism rate was 3.6% (n = 234) overall, 2.6% for colonoscopy, 2.9% for EGD and 4.3% for flexible sigmoidoscopy. Of the 234 patients, 50% were scheduled for colonoscopy, 35% for EGD and 15% for flexible sigmoidoscopy.

| Factor | Number of patients (n) | |||

| Control group1 | No-show | Total patients evaluated | ||

| Urgent procedure | No | 219 | 198 | 417 |

| Yes | 99 | 50 | 149 | |

| Direct to endoscopy | No | 235 | 187 | 422 |

| Yes | 81 | 75 | 156 | |

| Referring doctor | No referral | 9 | 17 | 26 |

| GP | 293 | 235 | 528 | |

| Specialist | 19 | 33 | 52 | |

| Sex | Female | 176 | 152 | 328 |

| Male | 150 | 133 | 283 | |

| Time of procedure | 7:30-10:00 | 125 | 87 | 212 |

| 10:00-12:30 | 115 | 106 | 221 | |

| 12:30-15:00 | 86 | 92 | 178 | |

| Type of procedure | Colonoscopy | 177 | 129 | 306 |

| EGD | 109 | 107 | 216 | |

| Flex-sig | 40 | 49 | 89 | |

| Weekday | Monday | 53 | 61 | 114 |

| Tuesday | 58 | 65 | 123 | |

| Wednesday | 72 | 56 | 128 | |

| Thursday | 73 | 61 | 134 | |

| Friday | 70 | 42 | 112 | |

| Distance living from hospital | Within 10 miles | 201 | 194 | 395 |

| Within 60 miles | 106 | 74 | 180 | |

| Beyond 60 miles | 18 | 13 | 31 | |

| Previous endoscopy | No | 132 | 104 | 236 |

| Yes | 184 | 144 | 328 | |

| New patient | No | 153 | 135 | 288 |

| Yes | 161 | 133 | 294 | |

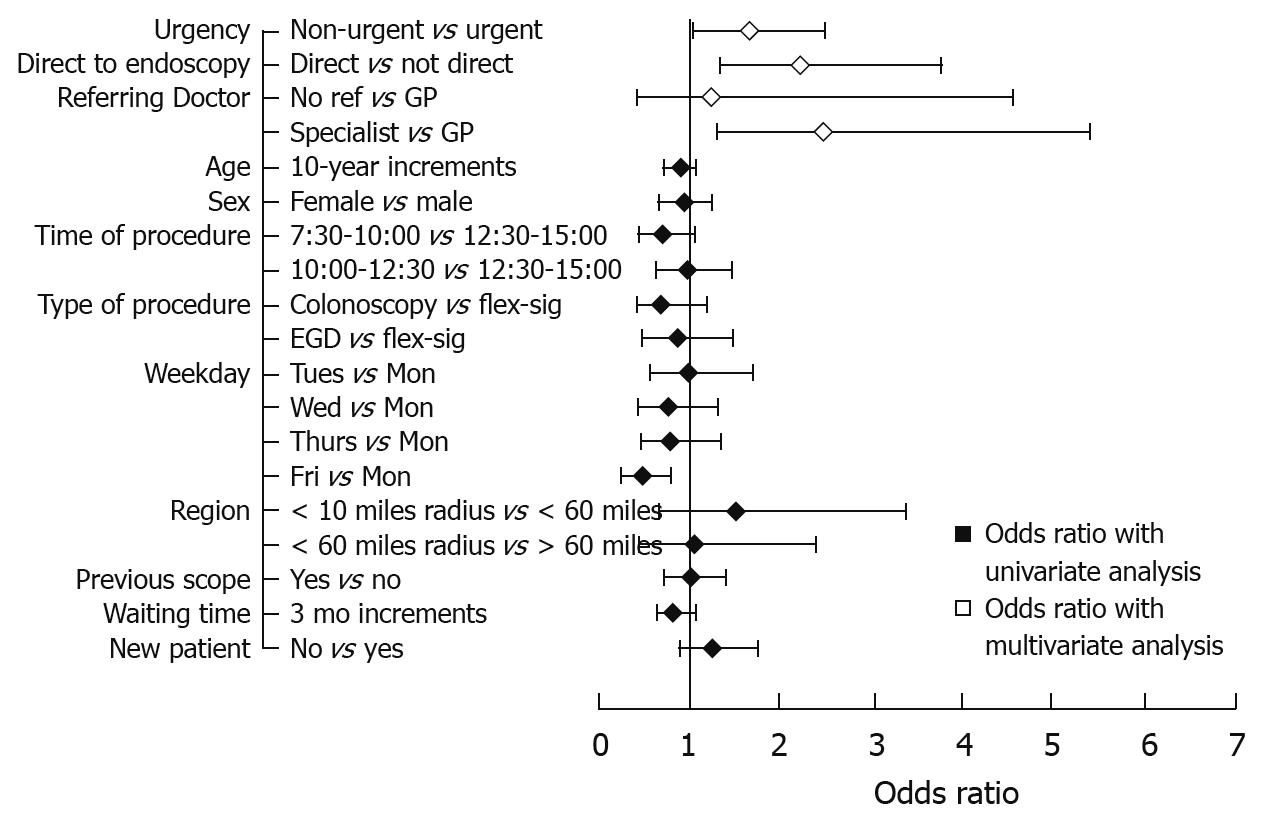

Univariate analysis was performed on each factor to determine the possibility of independent associations with patient “no shows” (Table 2, Figure 1) In the univariate analysis, a significant trend was determined towards truancy in those non-urgently referred (OR 1.79, 95% CI 1.2-2.6) and those referred from specialists (as opposed to family physicians) (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.2-3.9). Interestingly, in the univariate analysis, having their procedure performed on Friday (as opposed to Monday to Thursday) was protective against truancy (OR 0.493, 95% CI 0.28-0.87).

| Comparison | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Urgency | Non-urgent vs urgent | 1.790 | 1.211, 2.645 | 0.0035 |

| Direct to endoscopy | Not direct vs direct | 0.859 | 0.595, 1.242 | 0.4199 |

| Referring physician | Specialist vs GP | 2.165 | 1.200, 3.906 | 0.0063 |

| No referral vs GP | 2.355 | 1.031, 5.379 | ||

| Age | Increments of 10 years | 0.912 | 0.823, 1.010 | 0.0757 |

| Sex | Female vs male | 0.974 | 0.708, 1.340 | 0.8714 |

| Time of procedure | 7:30-10:00 vs 12:30-15:00 | 0.651 | 0.423, 1.001 | 0.0835 |

| 10-12:30 vs 12:30-15:00 | 0.967 | 0.637, 1.468 | ||

| Type of procedure | Colonoscopy vs flex-sig | 0.741 | 0.439, 1.250 | 0.2757 |

| EGD vs flex-sig | 0.964 | 0.558, 1.667 | ||

| Weekday | Tues vs Mon | 1.000 | 0.580, 1.723 | 0.9570 |

| Wed vs Mon | 0.754 | 0.439, 1.293 | ||

| Thurs vs Mon | 0.809 | 0.476, 1.373 | ||

| Fri vs Mon | 0.493 | 0.278, 0.873 | ||

| Region | < 10 mile radius vs < 60 mile radius | 1.537 | 0.685, 3.448 | 0.1110 |

| < 60 mile radius vs > 60 mile radius | 1.054 | 0.454, 2.449 | ||

| Previous endoscopy | Yes vs no | 1.039 | 0.738, 1.464 | 0.8252 |

| Waiting time | 3 mo increments | 0.835 | 0.675, 1.034 | 0.0980 |

| New patient | No vs yes | 1.293 | 0.921, 1.815 | 0.1369 |

Multivariate analysis was then performed to determine which factors were most associated with a positive outcome (Table 3, Figure 1). In the multivariate analysis three factors were statistically significant determinants in predicting “no shows”: (1) patients referred to the clinic for a non-urgent compared to urgent procedures (OR 1.624, 95% CI 1.06, 2.45); (2) patients referred by a specialist compared to those referred by a family doctor (OR 2.76, 95% CI 1.31, 5.524); (3) patients who had an office-based consult prior to the endoscopy as compared to those who went direct to the endoscopy suite for a consult and procedure during the same appointment (OR 2.244, 95% CI 1.33, 3.78). In the multivariate analysis, day of the week the procedure was performed was no longer significant. Figure 1 summarizes the findings of the univariate analysis and the significant factors on the multivariate analysis.

| Comparison | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Urgency | Non-urgent vs urgent | 1.624 | 1.056, 2.497 | 0.027 |

| Direct to endoscopy | Not direct vs direct | 2.244 | 1.331, 3.783 | 0.002 |

| Referring physician | Specialist vs GP | 2.763 | 1.383, 5.519 | 0.058 |

| No referral vs GP | 1.228 | 0.321, 4.706 | 0.666 |

There are many factors that are critical in maintaining the efficiency of an endoscopy unit. Many of these factors, such as emergency procedures, equipment failures and sedation difficulties are virtually impossible to predict. The multitasking, late physician is another major cause of an inefficient endoscopy unit and likewise, he/she is admittedly difficult to modify. On the other hand, truancy among patients who fail to attend their scheduled appointment is something that, in theory at least, has the capacity to be controlled.

We have determined the absenteeism rate in our endoscopy unit to be 3.6%, which encompassed 4.3% of flexible sigmoidoscopies, 2.6% of colonoscopies and 2.9% of upper endoscopies. This study was not designed to compare the absenteeism rates between the different procedures; however, when compared, these rates are not statistically different. We determined three factors that resulted in a patient being considered “high risk” for truancy. It has become common for patients to have a consultation and endoscopy at the same time, just prior to the endoscopy (particularly for screening colonoscopies), and we have found that these patients are more likely to attend their appointment than those who have been previously seen in an office setting by the physician. At present, in our setting, we do not use physician assistants, however, all patients scheduled for a consult and endoscopic procedure at the same time are called by a secretary with subsequent explanation of the preparation and procedure. Those patients who continue to have additional questions that cannot be answered by the secretary are scheduled for an office visit prior to the procedure. The practice of “direct to endoscopy” has become commonplace and we note that this practice has indeed apparently minimized our truancy rates. It should also be recognized that in our Canadian system, many patients are booked for their endoscopic procedures weeks to months in advance and yet, despite this, we still have improved attendance rates for those patients that are booked directly to endoscopy, possibly demonstrating a more motivated patient group. It does confirm that this practice at least results in appropriate attendance to endoscopy and that these patients are compliant with their appointment.

The second factor found to be associated with absenteeism from endoscopy was referral from a specialist rather than a family physician. This is logical in that family physicians are very accustomed to referring patients to a specialist and have an organized system to arrange it. On the other hand, many specialists’ offices are very adept at accepting referrals but not nearly as organized when it comes to referring a patient to another specialist. In addition, patients referred from other specialists often tend to have multiple health issues and more likely to be at a more acute state of illness. Just the fact that they have multiple health problems may put them at risk for absenteeism from their scheduled endoscopic appointment. This is another group of patients that can relatively easily be targeted as “high risk” for absenteeism and steps taken to ensure confirmation of their appointment.

The last group of patients who are more likely not to attend their appointments are those with non-urgent reasons for endoscopy. We defined urgent as those patients with bleeding or radiological abnormalities requiring endoscopic assessment. These patients are more likely to attend their procedure as opposed to the truly elective patient. This is logical in that typically, these patients have been told that there is a high likelihood that an abnormality is present and tissue confirmation is critical. These patients are therefore concerned enough to ensure their attendance at their endoscopic examination.

An Australian study demonstrated that patients with previous history of non-attendance were more likely not to attend[8], we have not found that in this study. This may be because if a patient doesn’t attend the endoscopy clinic at a scheduled time, typically, the physician will not arrange another endoscopy until another office visit has been completed and an explanation for truancy extracted. A pediatric study demonstrated that social factors (social class, unmarried parents, poorer housing) played a larger role in increasing truancy than other factors such as severity of disease[13]. Due to the nature of this study, assessment of social factors was not performed.

There are several limitations of our study. It is retrospective and contains the usual limitations inherent within this study design. On the other hand, there is presently very limited data available from the literature to determine who is at high risk for truancy from endoscopy units. Many endoscopic sites have instituted measures to limit truancy such as calling all patients by phone or mailing reminders prior to the endoscopic examination to ensure their attendance[1–3714]. Some of these measures are labor intensive with associated cost expenditures. Additionally, most patients attend their clinic appointment and in theory, don’t require a reminder. If a select group of patients could be targeted then a limited reminder protocol might be considered. Before we embarked upon any campaign to decrease truancy rates, we felt it was critical to determine what factors were important in this area. Ideally, if we could isolate several factors, steps could be undertaken to improve the system and then re-evaluate after institution of an improved management strategy.

Another limitation of our study is the fact that it applies only to the dataset of our institution and our patients. Its general, applicability may be questioned; however, our site is very similar to many tertiary care centers. Many patients come directly to the endoscopy unit without prior consultation, procedures are performed in large numbers with rapid turnover, the endoscopic rooms and time are the critical elements to the efficiency of any unit. As a tertiary care center with a wide base of referrals, it would appear that our unit is, in fact, similar to many other endoscopic units throughout the world and therefore, our results could likely be replicated elsewhere.

A final limitation of the study is the fact that we have excluded patients who were transferred from other hospitals as well as those scheduled for ERCP and EUS. These patients are more complex with a myriad of other issues (including the acuity of illness) and we felt that the group we needed to concentrate on was those in whom we perform most of the standard, elective endoscopic examinations.

In summary, we found that patients with a non-urgent condition, those referred from a specialist and those who do not have a consult and procedure at the same time are more likely to be absent from their scheduled endoscopic procedure than those without these characteristics. With this information, endoscopy units can hopefully modify their clinical practices to reduce patient truancy. Studies aimed at improving efficiency in endoscopy units should be aware of these “high-risk” patients to enhance appropriate resource utilization by decreasing absenteeism.

Patient absenteeism of outpatient procedures is a major problem for all ambulatory clinics.

Identifying patients who may not present for scheduled endoscopy may help gastroenterologists to reduce patient truancy.

Previous studies have shown that patients at highest risk for truancy are those with a history of truancy; and methods to enhance patient attendance at clinics (i.e. telephone reminders, mailed reminders) have had mixed results.

Identifying patients who are not scheduled for same-day consult and endoscopy, those referred by a specialist rather than a family physician, and those with non-urgent reasons for referral may help gastroenterologists to reduce patient truancy.

This manuscript is of enough interest and describes original work that merits its publication in WJG.

| 1. | Lee CS, McCormick PA. Telephone reminders to reduce non-attendance rate for endoscopy. J R Soc Med. 2003;96:547-548. |

| 2. | Downer SR, Meara JG, Da Costa AC. Use of SMS text messaging to improve outpatient attendance. Med J Aust. 2005;183:366-368. |

| 3. | Denberg TD, Coombes JM, Byers TE, Marcus AC, Feinberg LE, Steiner JF, Ahnen DJ. Effect of a mailed brochure on appointment-keeping for screening colonoscopy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:895-900. |

| 4. | Denberg TD, Melhado TV, Coombes JM, Beaty BL, Berman K, Byers TE, Marcus AC, Steiner JF, Ahnen DJ. Predictors of nonadherence to screening colonoscopy. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:989-995. |

| 5. | Turner BJ, Weiner M, Yang C, TenHave T. Predicting adherence to colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy on the basis of physician appointment-keeping behavior. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:528-532. |

| 6. | Takacs P, Chakhtoura N, De Santis T. Video colposcopy improves adherence to follow-up compared to regular colposcopy: a randomized trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2004;270:182-184. |

| 7. | Adams LA, Pawlik J, Forbes GM. Nonattendance at outpatient endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2004;36:402-404. |

| 8. | Collins J, Santamaria N, Clayton L. Why outpatients fail to attend their scheduled appointments: a prospective comparison of differences between attenders and non-attenders. Aust Health Rev. 2003;26:52-63. |

| 9. | Sawyer SM, Zalan A, Bond LM. Telephone reminders improve adolescent clinic attendance: a randomized controlled trial. J Paediatr Child Health. 2002;38:79-83. |

| 10. | Bos A, Hoogstraten J, Prahl-Andersen B. Failed appointments in an orthodontic clinic. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;127:355-357. |

| 11. | Maxwell S, Maljanian R, Horowitz S, Pianka MA, Cabrera Y, Greene J. Effectiveness of reminder systems on appointment adherence rates. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2001;12:504-514. |

| 12. | Murdock A, Rodgers C, Lindsay H, Tham TC. Why do patients not keep their appointments? Prospective study in a gastroenterology outpatient clinic. J R Soc Med. 2002;95:284-286. |

| 13. | McClure RJ, Newell SJ, Edwards S. Patient characteristics affecting attendance at general outpatient clinics. Arch Dis Child. 1996;74:121-125. |

| 14. | Abuksis G, Mor M, Segal N, Shemesh I, Morad I, Plaut S, Weiss E, Sulkes J, Fraser G, Niv Y. A patient education program is cost-effective for preventing failure of endoscopic procedures in a gastroenterology department. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1786-1790. |