Published online Jun 14, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2809

Revised: May 11, 2009

Accepted: May 18, 2009

Published online: June 14, 2009

Meckel’s diverticulum (MD) is the most frequent congenital abnormality of the small bowel and it is often difficult to diagnose. It is usually asymptomatic but approximately 4% are symptomatic with complications such as bleeding, intestinal obstruction, and inflammation. The authors report a case of a 7-year-old boy with a one-year history of recurrent periumbilical colicky pain with associated alimentary vomiting, symptoms erroneously related to a cyclic vomiting syndrome but not to MD. The clinical features and the differential diagnostic methods employed for diagnosis of MD are discussed.

- Citation: Codrich D, Taddio A, Schleef J, Ventura A, Marchetti F. Meckel’s diverticulum masked by a long period of intermittent recurrent subocclusive episodes. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(22): 2809-2811

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i22/2809.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.2809

Meckel’s diverticulum (MD) occurs in about 2% of the population, making it the most prevalent congenital abnormality of the gastrointestinal tract. It can be asymptomatic or mimic common abdominal disorders. We report a case of a child with an intraoperative diagnosis of MD, with a long history of recurrent abdominal pain and vomiting misdiagnosed as a cyclic vomiting syndrome.

A 7-year-old boy was referred with a one-year history of periumbilical colicky pain with associated alimentary vomiting. The frequency of the episodes increased from one per month to weekly and then daily vomiting. The pain usually spontaneously disappeared within a few hours. During the weeks before our visit, the painful episodes lasted longer and were reported to occur also at night. The child lost one kilogram in one month. No diarrhoea was reported, the boy was rather constipated. Previous medical investigations, abdominal ultrasonography and plain abdominal film were negative.

Neither abdominal tenderness, nor liver or spleen enlargement, nor abdominal masses were identified at palpation. Intestinal bacterial overgrowth and celiac disease were excluded by laboratory tests. Complete blood cell count, electrolytes, glycemia, blood ammonia, renal and hepatic function, pancreatic enzymes, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and gamma globulins were within normal ranges.

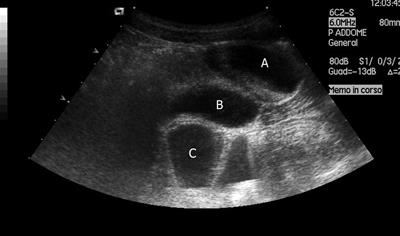

A plain abdominal film was unremarkable, and a small bowel enema indicated normal transit and normal appearance of the intestinal loops. An abdominal ultrasound (US) revealed a supravesical anechoic mass of about 4 cm × 3 cm × 2 cm, with fluid inside (Figure 1).

Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed the presence of the 4 cm mass, located above and behind the bladder, slightly to the right of the midline, with liquid content (Figure 2).

With the suspicion of a mesenteric cyst or an intestinal duplication, the child underwent an exploratory laparoscopy. The intraoperative macroscopic finding was that of MD. Diagnosis was confirmed by histological features.

MD is the most common congenital anomaly of the gastrointestinal tract. The “rule of two” can remind us of some of its main features: occurs in 2% of the population; usually discovered before 2 years of age; occurs within 2 feet of the ileocecal valve; is 2 inches long and 2 cm in diameter[1]. It is the result of an incomplete atrophy of the omphalomesenteric duct. The location of the diverticulum is on the antimesenteric border of the small intestine, most frequently between 30 cm and 90 cm from the ileocecal valve; there can be a fibrous connection to the umbilicus, as the remnant of the partially obliterated vitelline duct.

MD is a true diverticulum, composed of all layers of the intestinal wall, and is lined by normal small intestine epithelium. Gastric heterotopias can be found in roughly 50% of cases, and pancreatic, duodenal, colonic, or biliary mucosa have rarely been reported.

MD can be silent all through a lifetime: clinical symptoms arise from complications (MD carriers have a 4% lifetime risk of developing a complication)[2]. Hemorrhage is the result of peptic ulceration of the ileal mucosa next to an acid-producing gastric mucosal heterotopia: the presentation of the blood loss varies from recurrent minimal intestinal bleeding, to a massive, shock-producing hemorrhage, and it is usually painless. Diverticulitis can mimic an acute appendicitis: pain is frequently localized in the midline or slightly to the right and, as in appendiceal disease, inflammation can progress until perforation. The diverticulum can invert into the ileal lumen and become the starting point of an ileo-ileal or ileo-ileo-colic intussusception: symptoms can not be discriminated from those ascribed to idiopathic intussusception, even though the onset of the former is described to occur at an earlier age. A further mechanism by which MD can produce intestinal obstruction is to turn around a fibrous remnant: symptoms may vary from intermittent recurrent subocclusive episodes, as in our patient, to frank occlusion with strangulation features if a complete volvulus occurs[3]. “Littre hernia” occurs when a MD protrudes into a potential abdominal opening such as umbilical, inguinal, or femoral, and can be accompanied in some cases by entrapment, inflammation, and necrosis[1]. Tumors are reported in 0.5% to 3% of symptomatic diverticula in adulthood (carcinomas in one third of the cases)[3].

Preoperative diagnosis of a complicated MD can be challenging and often difficult to establish because clinical symptoms and imaging features overlap with those of other disorders causing acute abdominal pain or gastrointestinal bleeding[4].

Initially, our case was misdiagnosed as a cyclic vomiting syndrome and a functional abdominal pain, since neither inflammatory nor bleeding clinical features were present, and laboratory tests were substantially within normal ranges. If any bleeding episode had been reported, a 99mTc-pertechnetate scintigraphy would have been indicated: the principle is that a bleeding diverticulum consists of ulcerated ectopic gastric mucosa that can be revealed with 99mTc-pertechnetate. This concentrates in gastric tissue leading to a reported sensitivity of between 60% and 80%[5].

The progressive worsening of painful episodes, however, prompted us to exclude causes of pain and vomiting requiring surgery, such as intestinal malrotation, which was ruled out by a normal small bowel enema. It is reported in the literature that enteroclysis may be of help in detecting MD but in our case the diverticular image was missed[6].

The US findings of a cyst supported the suspicion of a surgery-indicated cause for the painful episodes, but other gut malformations such as mesenteric cysts or enteric duplications, both of which can present with subocclusive symptoms, were taken into account in the differential diagnoses of our child. US and computed tomography are reported in the literature to be valuable radiological investigations in MD patients without the classical history of painless hemorrhage[78].

Complicated MD has a spectrum of radiological features which may help in the preoperative investigations, but are not always diagnostic[7–9]. Our rationale in choosing MRI as a second-line radiological examination lay in the fact that we needed a better anatomical definition of what we suspected was a pelvic mass, without further irradiation of the child: there is no evidence for the use of MRI to detect MD in the literature. Final diagnosis is almost always done at surgery: exploratory laparoscopy is recommended because it affords the possibility of simultaneous surgical resection, which is the definitive cure of a symptomatic MD[10] .

In conclusion, Although MD is the most prevalent congenital abnormality of the gastrointestinal tract, it is often difficult to diagnose. The diagnosis of MD should be considered in children with intestinal bleeding, unexplained recurrent abdominal pain, and nausea and vomiting suggestive of cyclic vomiting syndrome.

| 1. | Skandalakis PN, Zoras O, Skandalakis JE, Mirilas P. Littre hernia: surgical anatomy, embryology, and technique of repair. Am Surg. 2006;72:238-743. |

| 2. | Martin JP, Connor PD, Charles K. Meckel’s diverticulum. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61:1037-1042, 1044. |

| 3. | Yahchouchy EK, Marano AF, Etienne JC, Fingerhut AL. Meckel’s diverticulum. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:658-662. |

| 4. | McCollough M, Sharieff GQ. Abdominal pain in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;53:107-137, vi. |

| 5. | Poulsen KA, Qvist N. Sodium pertechnetate scintigraphy in detection of Meckel’s diverticulum: is it usable? Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2000;10:228-231. |

| 6. | Sommers S. Congenital and developmental abnormalities of the small bowel. Radiological imaging of the small intestine. Berlin-Heidelberg: Springer 2002; 216-219. |

| 7. | Elsayes KM, Menias CO, Harvin HJ, Francis IR. Imaging manifestations of Meckel’s diverticulum. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:81-88. |

| 8. | Thurley PD, Halliday KE, Somers JM, Al-Daraji WI, Ilyas M, Broderick NJ. Radiological features of Meckel’s diverticulum and its complications. Clin Radiol. 2009;64:109-118. |

| 9. | Daneman A, Lobo E, Alton DJ, Shuckett B. The value of sonography, CT and air enema for detection of complicated Meckel diverticulum in children with nonspecific clinical presentation. Pediatr Radiol. 1998;28:928-932. |

| 10. | Shalaby RY, Soliman SM, Fawy M, Samaha A. Laparoscopic management of Meckel’s diverticulum in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:562-567. |