Published online Jun 14, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2748

Revised: May 5, 2009

Accepted: May 12, 2009

Published online: June 14, 2009

AIM: To evaluate the usefulness of pre-endoscopic serological screening for Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) infection and celiac disease in women aged < 50 years affected by iron-deficiency anemia (IDA).

METHODS: One hundred and fifteen women aged < 50 years with IDA were tested by human recombinant tissue transglutaminase IgA antibodies (tTG) and anti-H pylori IgG antibodies. tTG and H pylori IgG antibody were assessed using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). All women were invited to undergo upper GI endoscopy. During gastroscopy, biopsies were collected from antrum (n = 3), gastric body (n = 3) and duodenum (n = 4) in all patients, irrespective of test results. The assessment of gastritis was performed according to the Sydney system and celiac disease was classified by Marsh’s System.

RESULTS: 45.2% women were test-positive: 41 patients positive for H pylori antibodies, 9 patients for tTG and 2 patients for both. The gastroscopy compliance rate of test-positive women was significantly increased with respect to those test-negative (65.4% vs 42.8%; Fisher test P = 0.0239). The serological results were confirmed by gastroscopy in 100% of those with positive H pylori antibodies, in 50% of those with positive tTG and in 81.5% of test-negative patient. Sensitivity and specificity were 84.8% and 100%, respectively for H pylori infection and, 80% and 92.8% for tTG. Twenty-eight patients had positive H pylori antibodies and in all the patients, an active H pylori infection was found. In particular, in 23 out of 28 (82%) patients with positive H pylori antibodies, a likely cause of IDA was found because of the active inflammation involving the gastric body.

CONCLUSION: Anti-H pylori IgG antibody and tTG IgA antibody testing is able to select women with IDA to submit for gastroscopy to identify H pylori pangastritis and/or celiac disease, likely causes of IDA.

-

Citation: Vannella L, Gianni D, Lahner E, Amato A, Grossi E, Fave GD, Annibale B. Pre-endoscopic screening for

Helicobacter pylori and celiac disease in young anemic women. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(22): 2748-2753 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i22/2748.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.2748

Iron-deficiency anemia (IDA) is common in women aged < 50 years with a prevalence of almost 5% in Western countries[1]. In this population, the balance of iron is often precarious due to menses, pregnancy and breastfeeding and an excessive menstrual flow is experienced by about 30% of women of reproductive age[2]. Menorrhagia is often considered the only cause of iron deficiency anemia, but some studies have shown the usefulness of a gastrointestinal (GI) tract evaluation by endoscopy, thus indicating a role of the upper and/or lower GI tract as a likely cause of IDA[34]. The vast majority of IDA GI causes affect the upper GI tract and, in particular, there is a high prevalence of conditions associated with iron malabsorption such as Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) related-pangastritis, celiac disease and atrophic body gastritis in IDA premenopausal women[56]. On the contrary, as already reported in previous studies, bleeding lesions are infrequent in these patients and in particular in women aged < 50 years[5–8].

The diagnostic workflow in young women affected by IDA is not clearly established. The British Society of Gastroenterology recommends gastroscopy only in IDA women younger than 45 years presenting with GI symptoms[9]. However, the major issue of GI evaluation is that symptoms are often mild and aspecific in IDA women and that gastroscopy is an invasive procedure associated with a high number of refusals[10]. Furthermore, in our previous work on IDA premenopausal women, gastroscopy was performed as part of the diagnostic protocol in all patients, but was deemed unnecessary in almost 30% of the studied women because they were affected only by menorrhagia[5].

As shown in a previous study, non-invasive tests might be helpful in the selection of IDA women having a high probability of being affected by iron malabsorption GI diseases, in order to better address endoscopy and to increase the patients’ compliance to the procedure[11].

The aim of the present study was to prospectively evaluate the usefulness of a pre-endoscopic serological screening for H pylori infection and celiac disease with the use of two tests (human recombinant tissue transglutaminase IgA antibodies and anti-H pylori IgG antibodies) in women aged < 50 affected by IDA in order to increase the compliance for gastroscopy.

Between January and July 2006, 400 consecutive women (median age; 38 years) aged < 50 years with iron deficiency anemia were referred to the “Centro delle Microcitemie” of Rome, a public health institution specialized in the diagnosis of thalassemia. In these women the presence of an anemia emerged because they had previously undergone a complete blood count due to fatigue and/or for routine check-up, and were thus referred by their primary care physicians (60%), gynecologists (25.4%), hematologists (7.3%) or other physicians (7.3%) to the above mentioned center in order to exclude alpha- or beta-thalassemia minor, a frequent genetic disorder in the Italian population. In the “Centro delle Microcitemie”, a complete blood count, serum iron and ferritin were repeated in all patients, and after the exclusion of α- and β-thalassemia, the presence of IDA was definitely diagnosed. IDA was defined as hemoglobin (Hb) < 12 g/dL with serum ferritin ≤ 20 &mgr;g/dL.

IDA women were invited to answer a structured questionnaire to assess demographic data, previous iron supplementation, previous blood transfusion, previous hospitalization for anemia, obvious causes of blood loss, use of drugs (such as aspirin/NSAIDs, proton pump inhibitors, anticoagulants), 1st degree family history for colon or gastric cancer, peptic ulcer and celiac disease, type of diet, premenopausal status and GI symptoms. The duration of anemia was expressed as length of time from first diagnosis of IDA (mo) based on medical records. Upper GI symptoms included nausea, vomiting, dysphagia, heartburn, dyspepsia and upper abdominal pain. Lower GI symptoms included diarrhea, constipation, lower abdominal pain and hematochezia. The symptom was considered “present” if the patient referred to its presence at least once a week during the last three months[10]. Premenopausal status was defined as the patients’ personal reports that within 3 mo prior to evaluation they were still menstruating[5].

The women were excluded from the study if they had: age > 50, obvious causes of GI bleeding, previous diagnosis of GI diseases probably responsible for IDA based on medical records, anorexia, vegetarian diet, pregnancy, breastfeeding, anemia of chronic diseases (for example chronic renal failure, cirrhosis and severe cardiopulmonary disease) and hematological diagnoses (e.g. aplastic anemia, myelodysplasia).

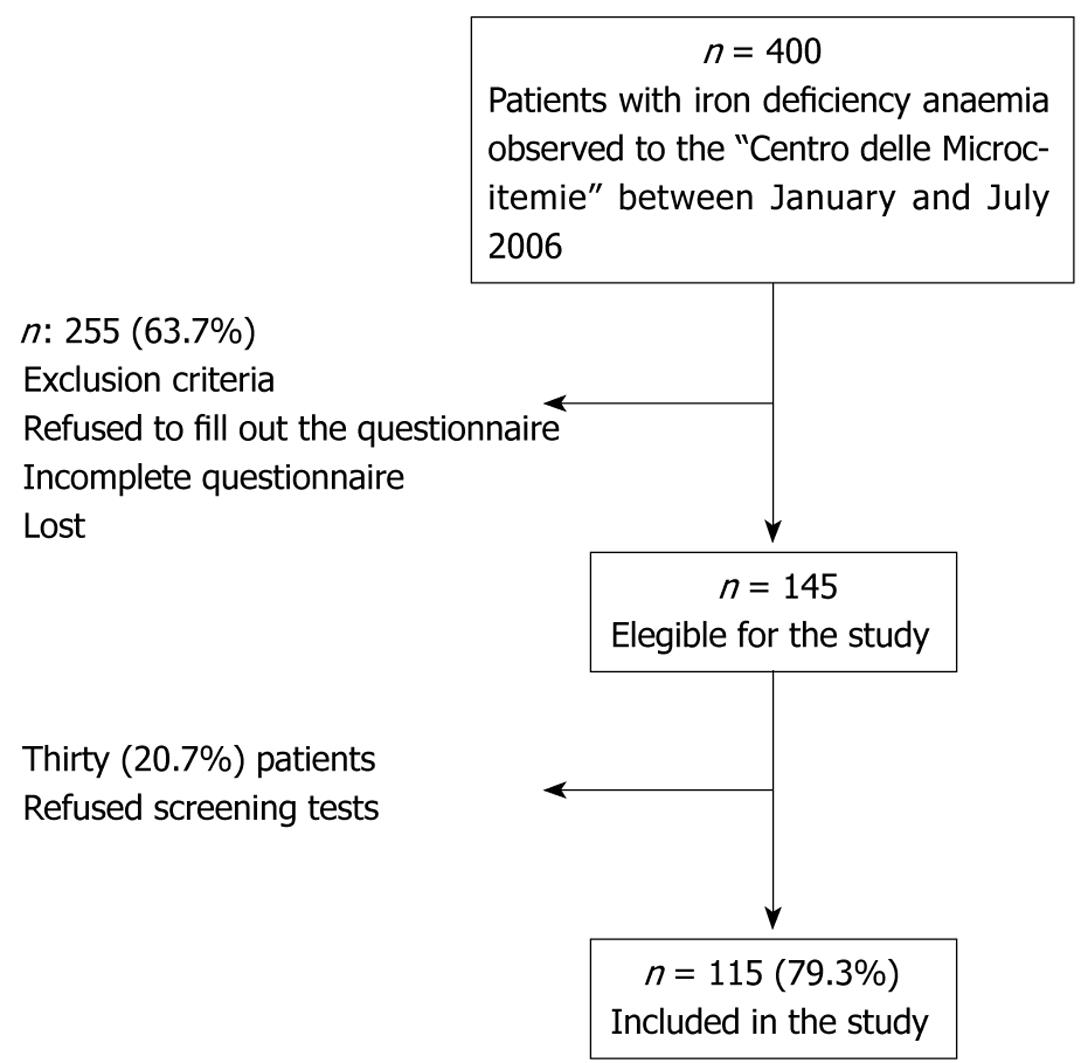

As shown in Figure 1, out of the initial 400 women with IDA, 145 women were considered eligible for the study (Figure 1). The diagnostic work-up included serological tests for the testing of anti-H pylori IgG antibodies to evaluate the presence of H pylori infection and tissue transglutaminase IgA antibodies to diagnose celiac disease. However, 30 women refused screening tests and thus, 115 women were included in the study and gave their informed consent.

Thus, 115 women were referred to University Gastroenterology Department to pick up test results and were invited to undergo upper GI endoscopy to confirm test results. Patients with at least one of the 2 tests positive were defined as “test-positive” patients, those with all 2 tests negative were defined as “test-negative” patients.

Serologic testing: Human recombinant tissue transglutaminase IgA antibodies were assessed using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) based on a commercially available kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Milan, Italy). A titre > 15 UI/mL was considered positive. H pylori IgG antibodies were assessed using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) based on a commercially available kit (Biohit, Helsinki, Finland). A titre > 1.1 UI/mL was considered positive.

Gastroscopy and histological evaluation: During gastroscopy, biopsies were collected from antrum (n = 3), gastric body (n = 3) and duodenum (n = 4) in all patients, irrespective of tests results. The assessment of gastritis was performed according to the Sydney system[12]. Pangastritis was defined as the presence of acute and chronic inflammatory infiltrate both in the gastric antrum and body as previously described[13]. If the sum of the inflammatory scores (acute and chronic) showed a two-grade difference between the antrum and corpus, the gastritis was considered as “antrum-predominant” or “corpus-predominant”, respectively. Antrum-restricted gastritis was defined by the presence of acute and chronic inflammatory infiltrate exclusively in antrum according to the Sydney system[12]. Celiac disease was classified by Marsh’s System[14]. The pathologist was unaware of the serological screening results.

Standard descriptive statistics was expressed as median and range and evaluated by appropriate statistical test (Mann-Whitney). Proportions were compared with the Fisher exact test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The women included in the study had a median age of 38 years (range 21-50 years) and the median duration of IDA was 12 mo (range 1-408 mo). The value of median hemoglobin was 10.7 (range 7.3-11.9) g/dL, MCV was 72 (range 51-92) fL and ferritin was 10 (range 1-20) &mgr;g/L. Oral iron therapy was previously prescribed in 48 (41.7%) women. Only a small number of patients had previously needed blood transfusion (n = 3, 2.6%) or hospitalization for anemia (n = 8, 7%).

At least one symptom of the upper GI tract was present in 49.6% of patients (n = 57), while 57.4% of patients (n = 66) had a least one symptom of the lower GI tract. Reported GI symptoms were mainly non-specific, such as mild abdominal pain (24%) and bloating (46%). The vast majority of patients had a negative family history for GI diseases (80.8%): a family history for GI cancers or peptic ulcers was present only in 4.3% and 14% of patients, respectively. In 91.3% of women a premenopausal status was present.

Fifty-two out of 115 patients (45.2%) were “test-positive”. Of these, 41 (35.6%) patients had positivity for H pylori IgG antibodies, 9 (7.8%) patients for tissue transglutaminase IgA antibodies and 2 (1.7%) patients had positivity for both antibodies. As shown in Table 1, the group of patients with positive tests was not different from that with negative tests as far as clinical and biochemical features were concerned.

| Patients, n = 115 | Test-positive n = 52(45.2%) | Test-negative n = 63(54.8%) | P |

| Age (yr) | 38 (23-50) | 37.5 (21-50) | NS |

| Duration of Anemia (mo) | 12 (1-408) | 12 (1-312) | NS |

| Hb (g/dL) | 10.6 (7.3-11.9) | 10.9 (8-11.9) | NS |

| MCV (fl) | 71 (51-90) | 74 (58-92) | NS |

| Iron (&mgr;g/dL) | 22 (6-65) | 24.5 (9-52) | NS |

| Ferritin (&mgr;g/L) | 10 (1-31) | 10 (2-59) | NS |

| Smokers | 10 (19%) | 10 (16%) | NS |

| Previous therapy with iron | 22 (41.5%) | 26 (41.9%) | NS |

| Previous blood transfusion | 2 (3.8%) | 1 (1.8%) | NS |

| Previous therapy with vitamin B12 | 5 (9.4%) | 9 (14.5%) | NS |

| Previous therapy with folic acid | 18 (34%) | 20 (32.2%) | NS |

| Hospitalization for anemia | 3 (5.7%) | 5 (9.4%) | NS |

| Upper GI symptoms | 26 (49%) | 31 (50%) | NS |

| Lower GI symptoms | 29 (54.7%) | 37 (59.7%) | NS |

| Premenopausal status | 49 (94.2%) | 56 (88.9%) | NS |

“Test-Positive Patients”: Four women did not undergo gastroscopy because they become pregnant after the start of the study. Of these, 3 patients had positive H pylori antibodies and 1 patient positive tissue transglutaminase IgA antibodies. Fourteen patients refused the invasive procedure, 12 out of these patients had positive H pylori antibodies and 2 patients had positive tissue transglutaminase IgA antibodies. Thus, 34 out of 52 (65.4%) “test-positive” patients consented to the upper GI endoscopy and the results are shown in Table 2.

Twenty-eight patients had positive H pylori antibodies, and in all these patients an active H pylori infection was found. Celiac disease was confirmed only in 4 out of 8 (50%) patients with positive tissue transglutaminase IgA antibodies, whereas in another patient who underwent gastroscopy for positive H pylori antibodies, celiac disease was also found. Of the 5 patients with celiac disease, 4 had Marsh 3 and 1 had Marsh 2.

In Table 3, the extent and the degree of H pylori-related gastritis is shown. Five IDA women with positive H pylori antibodies had exclusively antrum-restricted gastritis with active H pylori infection. In the remaining patients (n = 23), a pangastritis with active H pylori infection was present which in 91.3% of cases showed equal severity of the inflammatory score in antrum and corpus. Thus, in 23 out of 28 (82%) patients with positive H pylori antibodies, a likely cause of IDA was found because the active inflammation involved the gastric body.

| Histological findings | Test-positive patients | Test-negative patients |

| Antrum-restricted gastritis | 5 | 2 |

| Pangastritis1 | 21 | 1 |

| Antrum-predominant pangastritis | 1 | 1 |

| Corpus-predominant pangastritis | 1 | - |

| Atrophic body gastritis | - | 1 |

| Total | n = 28 | n = 5 |

“Test-Negative Patients”: Three women could not undergo gastroscopy because they were pregnant, and 33 patients refused the procedure. Thus, 27 out of 63 (43%) “test-negative” patients underwent upper GI endoscopy. In 22 out of 27 (81.5%) patients, the negative serological tests results were confirmed because no gastroscopic/histological finding was revealed; instead in the remaining 5 patients H pylori gastritis was diagnosed (Table 2). In particular, 3 likely causes of IDA were misdiagnosed because 2 patients had “antral-predominant” chronic gastritis and 1 patient had atrophic body gastritis (Table 3).

The compliance rate of test-positive women (65.4%) was significantly higher than that of test-negative ones (42.8%) (Fisher test P = 0.0239). Patients undergoing gastroscopy were similar to the group of included patients in the study for demographic, clinical and biochemical data. Moreover, for these parameters, the group of dropped-out test-positive and test-negative patients was not different from those test-positive and test-negative patients who underwent gastroscopy (data not shown).

On the basis of these results, the sensitivity, the specificity, and the positive and negative predictive values of tissue transglutaminase IgA antibodies for the diagnosis of celiac disease were 80%, 92.8%, 50% and 98.1%, respectively. The sensitivity, the specificity, and the positive and negative predictive values of anti-H pylori antibodies for the diagnosis of H pylori infection were 84.8%, 100%, 100% and 84.8%, respectively.

In the present study, 115 women aged < 50 years with unexplained IDA were tested by anti-H pylori IgG antibodies and human recombinant tissue transglutaminase IgA antibodies to diagnose H pylori infection and celiac disease. Almost half of the studied patients tested positive for at least one serological assay, and the suspicion of an upper GI disease as likely cause of IDA, raised by the serological result, was confirmed by gastroscopy in 100% of those with positive H pylori antibodies and in 50% of those with positive tissue transglutaminase IgA. On the other hand, in only 11% of test negative patients, gastroscopy with biopsies yielded a finding which may be interpreted as a likely cause of IDA (2 H pylori-related antrum predominant pangastritis and 1 atrophic body gastritis). Thus, these findings indicate that in women aged < 50 years with IDA, the dual-step approach e.g. serological tests and then invasive procedure, may be considered as a useful tool to optimize the use of gastroscopy, avoiding useless procedures, and to reduce the number of expensive histological examinations.

Previous studies have shown that the presence of GI symptoms or the severity of anemia were related to higher risk of GI causes of IDA[356]. In this study, no difference was found between test-positive and test-negative patients in terms of personal data, clinical and biochemical features including the frequency of upper GI symptoms and Hb values. Therefore, our results show that GI evaluation is of poor utility to target IDA patients for gastroscopy, strengthening the usefulness of the pre-endoscopic screening by serological tests.

H pylori infection was found in 35.6% of the investigated women, confirming the strong association between H pylori infection and IDA observed in previous epidemiological studies[1516]. Since H pylori IgG antibodies do not discriminate between active or previous infection, they are not generally considered useful for diagnosing H pylori infection[17]; in this clinical setting of IDA women, H pylori antibody-positivity was always associated with active infection as shown by histological data (Table 3). Moreover, 82% of patients with H pylori antibody-positivity had gastritis involving the gastric body, while only five cases had an antrum-restricted gastritis. In fact, only when the inflammation involves the gastric body, the acid secretion is reduced and the iron absorption is impaired, is there a consequential IDA[1318]. The presence of positive H pylori antibodies, in a patient at high risk for iron malabsorption diseases, supports the need of an accurate gastroscopic/histological evaluation with antral and corporal biopsies to define the extent of gastritis and eventually its association with IDA. In our clinical setting, we observed 100% specificity and positive predictive value as well as a sensitivity of 85% for the H pylori antibodies assay. On the basis of this result, we believe that the assay of H pylori antibodies may be considered useful in the selection of IDA women aged < 50 years to submit for gastroscopy, also keeping in mind that this serological test is widely available and cheap and, for this reason, it may be used in the primary care.

Human recombinant tissue transglutaminase IgA antibodies were found to be positive in almost 7% of all patients. This antibody was chosen as screening test for celiac disease, because it is based on ELISA assay and is more accurate compared to the immunofluorescence method used for determining endomysial antibodies[19]. Our results showed a good sensitivity (80%), and specificity (93%) of the assay in keeping with a recent meta-analysis[20]. Our study confirmed also the poor positive predictive value (50%), which is a well known limit of this serological assay. Yet, this value is higher than the one (28%) reported in previous literature[21]. This difference may be explained by the fact that the women included in the present study were anemic and thus were at high risk for celiac disease[22]. Considering the occurrence of false positives of the tissue transglutaminase assay, even in this particular clinical setting, the need for a histological confirmation of celiac disease diagnosis is confirmed.

The main limitation of this work is the small size of the sample, in part due to the high percentage of patients who have refused to participate in the study and of those who, once included, refused gastroscopy. Thus, our findings suggest that the pre-selection of young women for gastroscopy by non-invasive serological testing is able to increase compliance for the invasive procedure. In fact, the compliance rate of test-positive women was significantly increased with respect to those test-negative (65.4% vs 42.8%; Fisher test P = 0.0239).

In conclusion, half of IDA women aged < 50 years tested positive to serological screening for H pylori infection and/or celiac disease, and gastroscopy with biopsies confirmed in the vast majority of them the presence of active H pylori gastritis involving gastric body, or celiac disease, as possible causes of IDA. Thus, two simple and widely available tests (tissue transglutaminase IgA antibodies and anti-H pylori IgG antibodies) are able to select women with IDA to submit for gastroscopy to identify IDA-related GI causes.

Iron-deficiency anemia (IDA) is common in women aged < 50 years. Menorrhagia is often considered the only cause of iron deficiency anemia, but some studies have shown the usefulness of a gastrointestinal (GI) tract evaluation. The vast majority of IDA GI causes affect the upper GI tract and there is a high prevalence of conditions associated with iron malabsorption such as Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) related-pangastritis, celiac disease and atrophic body gastritis in IDA premenopausal women.

The diagnostic workflow in young women affected by IDA is not clearly established. The British Society of Gastroenterology recommends gastroscopy only in IDA women younger than 45 years presenting with GI symptoms. However, symptoms are often mild and aspecific in IDA women and the gastroscopy is an invasive procedure associated with a high number of refusals. In a previous work on IDA premenopausal women, gastroscopy was performed in all patients, later deemed unnecessary in almost 30% of the studied women because these were affected only by menorrhagia.

This study showed that two simple and widely available tests, ie those for tissue transglutaminase IgA antibodies and anti-H pylori IgG antibodies, are able to select women with IDA to submit for gastroscopy to identify IDA-related GI causes and to increase the compliance for the invasive procedure. Gastroscopy with biopsies confirmed in the vast majority of IDA women the presence of active H pylori pangastritis, atrophic gastric body, or celiac disease as possible causes of IDA.

This study showed that a pre-endoscopic serological screening for H pylori infection and celiac disease is useful to select IDA women having a high probability of being affected by iron malabsorption GI diseases and to increase the patients’ compliance for the procedure.

Pangastritis: H pylori-related gastritis involving the antrum and the body of the stomach. Malabsorptive diseases: diseases related to iron-malabsorption that include H pylori-pangastritis, atrophic body gastritis and celiac diseases.

The paper is interesting to study the usefulness of non-invasive test to select women with IDA for gastroscopy. These findings may be not applicable to other countries if the prevalence of celiac disease or H pylori infection are low.

| 1. | Looker AC, Dallman PR, Carroll MD, Gunter EW, Johnson CL. Prevalence of iron deficiency in the United States. JAMA. 1997;277:973-976. |

| 2. | El-Hemaidi I, Gharaibeh A, Shehata H. Menorrhagia and bleeding disorders. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19:513-520. |

| 3. | Bini EJ, Micale PL, Weinshel EH. Evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract in premenopausal women with iron deficiency anemia. Am J Med. 1998;105:281-286. |

| 4. | Fireman Z, Zachlka R, Abu Mouch S, Kopelman Y. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation of iron deficiency anemia in premenopausal women. Isr Med Assoc J. 2006;8:88-90. |

| 5. | Vannella L, Aloe Spiriti MA, Cozza G, Tardella L, Monarca B, Cuteri A, Moscarini M, Delle Fave G, Annibale B. Benefit of concomitant gastrointestinal and gynaecological evaluation in premenopausal women with iron deficiency anaemia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:422-430. |

| 6. | Carter D, Maor Y, Bar-Meir S, Avidan B. Prevalence and predictive signs for gastrointestinal lesions in premenopausal women with iron deficiency anemia. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:3138-3144. |

| 7. | Park DI, Ryu SH, Oh SJ, Yoo TW, Kim HJ, Cho YK, Sung IK, Sohn CI, Jeon WK, Kim BI. Significance of endoscopy in asymptomatic premenopausal women with iron deficiency anemia. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:2372-2376. |

| 8. | Kepczyk T, Cremins JE, Long BD, Bachinski MB, Smith LR, McNally PR. A prospective, multidisciplinary evaluation of premenopausal women with iron-deficiency anemia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:109-115. |

| 9. | Goddard AF, McIntyre AS, Scott BB. Guidelines for the management of iron deficiency anaemia. British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut. 2000;46 Suppl 3-4:IV1-IV5. |

| 10. | Baccini F, Spiriti MA, Vannella L, Monarca B, Delle Fave G, Annibale B. Unawareness of gastrointestinal symptomatology in adult coeliac patients with unexplained iron-deficiency anaemia presentation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:915-921. |

| 11. | Annibale B, Lahner E, Chistolini A, Gailucci C, Di Giulio E, Capurso G, Luana O, Monarca B, Delle Fave G. Endoscopic evaluation of the upper gastrointestinal tract is worthwhile in premenopausal women with iron-deficiency anaemia irrespective of menstrual flow. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:239-245. |

| 12. | Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161-1181. |

| 13. | Capurso G, Lahner E, Marcheggiano A, Caruana P, Carnuccio A, Bordi C, Delle Fave G, Annibale B. Involvement of the corporal mucosa and related changes in gastric acid secretion characterize patients with iron deficiency anaemia associated with Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1753-1761. |

| 14. | Marsh MN. Gluten, major histocompatibility complex, and the small intestine. A molecular and immunobiologic approach to the spectrum of gluten sensitivity (‘celiac sprue’). Gastroenterology. 1992;102:330-354. |

| 15. | DuBois S, Kearney DJ. Iron-deficiency anemia and Helicobacter pylori infection: a review of the evidence. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:453-459. |

| 16. | Cardenas VM, Mulla ZD, Ortiz M, Graham DY. Iron deficiency and Helicobacter pylori infection in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:127-134. |

| 17. | Cutler AF, Prasad VM. Long-term follow-up of Helicobacter pylori serology after successful eradication. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:85-88. |

| 18. | Annibale B, Capurso G, Lahner E, Passi S, Ricci R, Maggio F, Delle Fave G. Concomitant alterations in intragastric pH and ascorbic acid concentration in patients with Helicobacter pylori gastritis and associated iron deficiency anaemia. Gut. 2003;52:496-501. |

| 19. | Lewis NR, Scott BB. Systematic review: the use of serology to exclude or diagnose coeliac disease (a comparison of the endomysial and tissue transglutaminase antibody tests). Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:47-54. |

| 20. | Zintzaras E, Germenis AE. Performance of antibodies against tissue transglutaminase for the diagnosis of celiac disease: meta-analysis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13:187-192. |

| 21. | Hopper AD, Cross SS, Hurlstone DP, McAlindon ME, Lobo AJ, Hadjivassiliou M, Sloan ME, Dixon S, Sanders DS. Pre-endoscopy serological testing for coeliac disease: evaluation of a clinical decision tool. BMJ. 2007;334:729. |

| 22. | Rostom A, Murray JA, Kagnoff MF. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technical review on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1981-2002. |