Published online May 21, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2401

Revised: January 19, 2009

Accepted: January 26, 2009

Published online: May 21, 2009

AIM: To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of capsule endoscopy (CE) in patients with recurrent subacute small bowel obstruction.

METHODS: The study was a retrospective analysis of 31 patients referred to hospital from January 2003 to August 2008 for the investigation of subacute small bowel obstruction, who underwent CE. The patients were aged 9-81 years, and all of them had undergone gastroscopy and colonoscopy previously. Some of them received abdominal computed tomography or small bowel follow-through.

RESULTS: CE made a definitive diagnosis in 12 (38.7%) of 31 cases: four Crohn’s disease (CD), two carcinomas, one intestinal tuberculosis, one ischemic enteritis, one abdominal cocoon, one duplication of the intestine, one diverticulum and one ileal polypoid tumor. Capsule retention occurred in three (9.7%) of 31 patients, and was caused by CD (2) or tumor (1). Two with retained capsules were retrieved at surgery, and the other one of the capsules was spontaneously passed the stricture by medical treatment in 6 mo. No case had an acute small bowel obstruction caused by performance of CE.

CONCLUSION: CE provided safe and effective visualization to identify the etiology of a subacute small bowel obstruction, especially in patients with suspected intestinal tumors or CD, which are not identified by routine examinations.

- Citation: Yang XY, Chen CX, Zhang BL, Yang LP, Su HJ, Teng LS, Li YM. Diagnostic effect of capsule endoscopy in 31 cases of subacute small bowel obstruction. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(19): 2401-2405

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i19/2401.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.2401

Small bowel obstruction is a frequent cause of acute abdomen. The definitive diagnostic rate is not high using traditional radiographic evaluation, such as plain film radiography, abdominal computed tomography (CT), or small bowel follow-through. Some reports have demonstrated that capsule endoscopy (CE) is superior to radiographic examination and push enteroscopy in the investigation of intestinal diseases, especially for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding or suspected Crohn’s disease (CD)[1–4]. Although capsule retention is a relatively infrequent complication, small bowel obstruction and strictures have been considered contraindications to CE. It is interesting to note that there is a controversy about this contraindication in the literature. The goal of the present study was to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of CE in patients with small bowel obstruction.

Between January 2003 and August 2008, 31 patients underwent CE for the investigation of small bowel obstruction, who had previously received gastroscopy and colonoscopy, abdominal CT or small bowel follow-through more than once. All previous radiological and endoscopic examinations could not identify clear etiology.

CE (Given M2A, Giving Imaging Ltd, Yoqneam, Israel) measuring 11 mm × 26 mm, which magnify images eight times, has a battery life of 6-8 h. It is used in conjunction with an imaging system including a data recorder and interpretative workstation. Continuous video-images are transmitted at a rate of two frames per second.

A total of 1121 patients underwent CE between January 2003 and August 2008. Most of them underwent CE for the evaluation of obscure bleeding or suspected CD. We identified 31 patients presenting with symptoms consistent with small bowel obstruction, and abdominal X-ray showed incomplete intestinal obstruction. All the 31 patients who were aware of an increased risk for capsule retention and the possibility for surgery received CE examination, when the symptoms of intestinal obstruction were relieved by conservative management. All the patients gave written informed consent. The medical data were retrospectively analyzed, including age, sex, medical and surgical history, follow-up, and radiographic, routine endoscopic and CE examinations.

The mean age of these 31 patients was 47.12 ± 18.38 years (range 9-81 years); 18 of the subjects were male and 13 were female. Seventeen of them were out-patients, 14 were in-patients, and nine had surgical histories before capsule examinations were performed. All of them had undergone gastroscopy and colonoscopy previously, but the results were negative. Twenty-three of them had undergone CT enterography or small bowel follow-through, and positive or suspected results were found in six cases. Four of the six patients achieved definitive diagnoses by CE examination, surgical or pathological biopsy, and the remaining two were false-positive.

The average gastric emptying time was 43.8 ± 36.1 min (range 4-131 min). In 15 of the 31 patients, the capsule passed the ileocecal valve within the duration of the examination. The mean small bowel transit time (based on 24 patients) was 332.2 ± 86.7 min (range 167-484 min, Table 1). In 28 of the 31 patients, the capsule was evacuated in 3 d. Capsule retention occurred in three (9.7%) cases, caused by CD or tumor, of which, were retrieved at surgery, and the other one of the capsules was spontaneously passed the stricture by medical treatment in 6 mo. None of the cases showed any symptoms of acute or subacute obstruction during CE examination.

| Patient | Gender/age (yr) | Surgical history/NSAID use | Prior examinations | GI transit time (min) | CE or surgical findings | Follow-up (mo) |

| 1 | M/43 | None | EGD, colonoscopy (-), AXR | 319 | Abdominal cocoon | 17 |

| 2 | F/18 | Appendectomy | EGD, colonoscopy (+), AXR | 387 | CD | 53 |

| 3 | M/74 | None | EGD, colonoscopy (-), AXR | 329 | Normal | 54 |

| 4 | F/69 | None | EGD, colonoscopy, SBFT (-), AXR | 295 | Normal | 53 |

| 5 | M/54 | None | Colonoscopy, SBFT (±), AXR | CE retention | CD | 29 |

| 6 | M/9 | Intussusception | EGD, colonoscopy (-), AXR | 205 | Normal | 16 |

| 7 | F/67 | None | EGD, colonoscopy (-), AXR | Not pass | Ischemic enteritis | Lost in 11 |

| 8 | F/36 | None | EGD, colonoscopy, CTE (-), AXR | 308 | Normal | 27 |

| 9 | M/46 | None | CTE (±), SBFT (±), AXR | 461 | Tumor | 15 |

| 10 | F/37 | Abdominal delivery | EGD, colonoscopy, SBFT (-), AXR | 247 | Normal | 17 |

| 11 | F/52 | None | EGD, colonoscopy, CTE, SBFT (-) | CE retention | Tumor | 2 |

| 12 | F/52 | None | EGD, colonoscopy, CTE, SBFT (-) | Not pass | Normal | 1 |

| 13 | F/62 | None | EGD, colonoscopy, CTE, SBFT (-) | Not pass | Normal | 2 |

| 14 | M/57 | None | EGD, CTE, SBFT (-), AXR | 324 | Normal | 33 |

| 15 | M/31 | None | EGD, colonoscopy (-), AXR | 250 | Normal | 32 |

| 16 | F/32 | None | EGD, colonoscopy (±), CTE (-) | 446 | Normal | 30 |

| 17 | M/53 | None | CTE (+), EGD/colonoscopy (-), | 346 | Normal | 33 |

| 18 | F/31 | Abdominal delivery | EGD/colonoscopy (-), US/CTE (+) | 425 | TB | 30 |

| 19 | M/22 | None | EGD/colonoscopy, SBFT (-), AXR | 340 | Normal | 3 |

| 20 | M/46 | Small bowel resection | EGD/colonoscopy, CTE (-), AXR | 296 | Normal | 3 |

| 21 | M/81 | None | Colonoscopy (-), AXR | 378 | Normal | Lost2 |

| 22 | F/54 | Tubal ligation | EGD/colonoscopy, CTE (-) | 458 | Normal | 41 |

| 23 | M/75 | None | EGD/colonoscopy (-), AXR | 327 | Normal | Death in 24 |

| 24 | M/53 | None | EGD/colonoscopy (-), AXR | 421 | CD | 51 |

| 25 | M/60 | None | EGD/colonoscopy, SBFT (-) | 465 | Intestinal diverticulum | 5 |

| 26 | F/52 | None | EGD/colonoscopy, CTE (±) | 465 | Normal | 16 |

| 27 | M/32 | None | EGD/colonoscopy (-), AXR | 293 | Normal | 39 |

| 28 | F/54 | Tubal ligation | EGD/colonoscopy, SBFT (-) | 354 | Normal | 36 |

| 29 | F/59 | None | EGD/colonoscopy, MRI (-), AXR | 349 | Ileal polypoid tumor | Lost2 |

| 30 | M/9 | None | EGD/colonoscopy, CTE (-), AXR | Not pass | Duplication of intestine | 12 |

| 31 | F/65 | None | EGD/colonoscopy, SBFT (-), AXR | CE retention | CD | 14 |

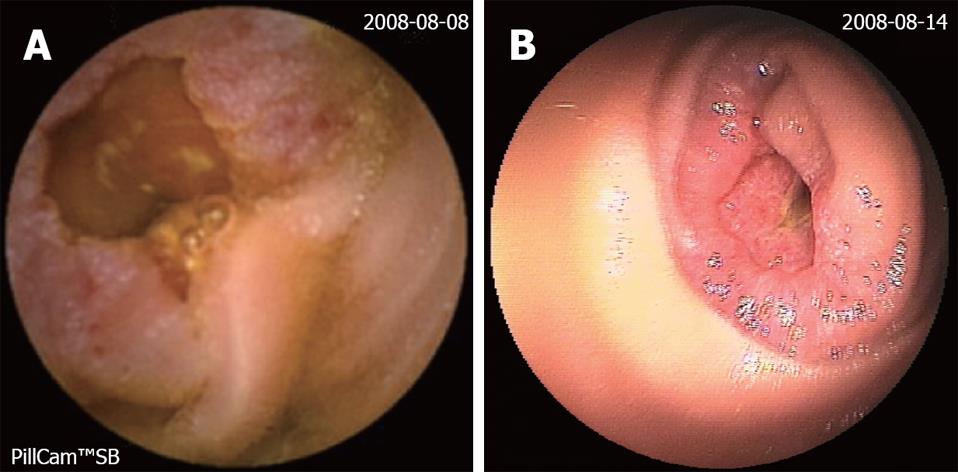

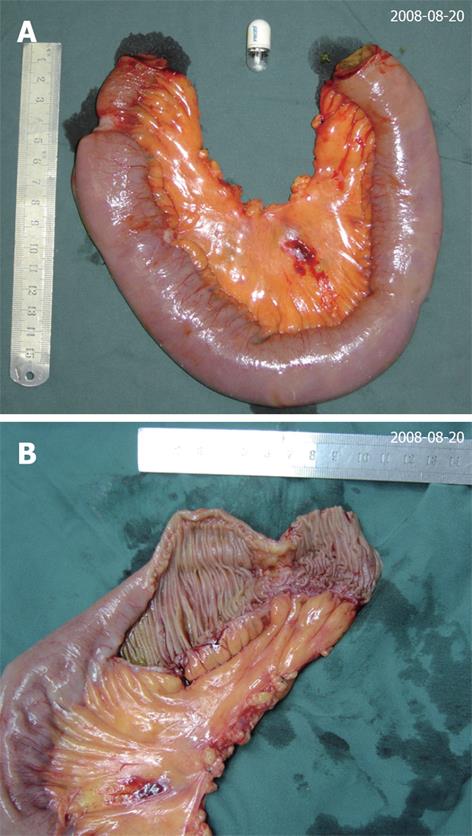

CE disclosed definitive intestinal disease in 12 (38.7%) of the 31 patients, including four CD, two carcinoma, one intestinal tuberculosis, one ischemic enteritis, one abdominal cocoon, one intestinal duplication, one small-intestinal diverticulum and one ileal polypoid tumor (Table 2). Single or multiple ulcers were found in six patients. In three of the six, CD was diagnosed by CE images and clinical manifestations, and obvious symptom relief was achieved through treatment with mesalazine. In one of the six patients, capsule was retrieved at surgery which had not passed the stricture for 7 d, and the replacement showed CD. In another of the six patients, multiple ulcers were found with CE and double-balloon enteroscopy. CD was firstly considered according to the endoscopic findings and clinical data, but medical treatment with mesalazine did not relieve the patient’s symptoms. The later BUS and CT scans showed multiple retroperitoneal lymph node enlargement, meanwhile, the purified protein derivative test was found to be positive. Pathological analysis of biopsy specimens obtained from these lymph nodes indicated tuberculosis. The patient’s symptoms were relieved significantly by anti-tuberculosis treatment, therefore, intestinal tuberculosis was diagnosed. The remainder of the six was demonstrated abdominal cocoon at surgery. In one elderly patient, intestinal mucosal erosion and bleeding were found at CE examination. Later, exploratory laparotomy was performed for advanced identification of etiology and therapy, which indicated superior mesenteric artery embolus. In another case, the capsule images presented abnormal intestinal motility and CT scan showed mural thickening of the distal ileum, and finally, ileal neuroendocrine carcinoma was diagnosed by surgery. In a pediatric case, CE also showed abnormal intestinal motility. The child was treated surgically because of failure of medical treatment, which indicated duplication of the intestine. The CE findings in the remaining two cases disclosed diverticulum of the small intestine and ileal polypoid tumor. In a female patient whose CA199 increased clearly CT, BUS scan or air-barium double contract examination were negative, but CE and double air-balloon endoscopy showed an annuliform mass, which was demonstrated to be jejunal adenocarcinoma at later surgery (Figures 1 and 2).

| Detected abnormalities (12) | Gender/age (yr) | CE retention (time) | Therapy | Post-CE obstructive symptom |

| CD (4) | ||||

| F/18 | No | Medical therapy | None | |

| M/54 | Yes (1 wk) | Surgical resection | None | |

| M/53 | No | Medical therapy | None | |

| F/65 | Yes (6 mo) | Medical therapy | None | |

| Tumor (2) | ||||

| Ileal neuroendocrine carcinoma | M/46 | No | Surgical resection | None |

| Jejunal adenocarcinoma | F/52 | Yes (2 wk) | Surgical resection | None |

| Intestinal tuberculosis (1) | F/31 | No | Medical therapy | None |

| Ischemic enteritis (1) | F/67 | No | Surgical resection | None |

| Abdominal cocoon (1) | M/43 | No | Surgical resection | None |

| Intestinal diverticulum (1) | M/60 | No | Medical therapy | None |

| Ileal polypoid tumor (1) | F/59 | No | Lost to follow-up | None |

| Duplication of intestine (1) | M/9 | No | Surgical resection | None |

None of the patients had other risk factors for stricture formation, such as long-term administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAIDs) and abdominal radiotherapy. The capsule images were normal in 19 of the 31 cases. Follow-up was missed in three of the 19 cases. An elderly patient in the remaining 16 died of pulmonary infection. Small bowel obstruction did not reappear in the other 15 cases during medical treatment in the follow-up period. However, adhesive ileus could not be excluded in four of the 14 patients who had a history of abdominal surgery. The capsule findings allowed a definitive diagnosis in 12 of the 31 cases: six patients accepted surgical treatment (one CD, two tumors, one ischemic enteritis, one abdominal cocoon, one duplication). Five patients (three CD, one intestinal tuberculosis, one intestinal diverticulum) were treated medically without surgery, and no recurrence of small bowel obstruction was found in these patients during follow-up.

CE is a novel diagnostic technique that has been used increasingly for analysis of many disorders of the small intestine, such as occult gastrointestinal bleeding, suspected CD, chronic diarrhea, and protein-losing enteropathy. Although small bowel obstruction has been considered a contraindication to CE, in our series, CE was documented to be very valuable and safe in identifying the etiology of small bowel obstruction, and it was also found to be easy to swallow, painless and well tolerated by these selected patients. CE findings allowed a definitive diagnosis in 12 (38.7%) out of the 31 cases, in which CD (4/31) was the major disease inducing stricture of the intestine. This cause was consistent with that in the study of Chiefetz and Lewis[5]. In contrast, some authors have reported that NSAID-induced stricture was the major cause of capsule retention[67]. Recently, Mason et al[8] have reported that intestinal mass or radiation enteritis are the main causes of subacute small bowel obstruction. The different causes of stricture may be associated with the indications of the patients.

The incidence of retention is closely related to the selected population. The incidence of retention varies from 0%-21% in the literature as a result of the different populations and indications for examination. The highest published rate (21%) was reported in the study of Chiefetz and Lewis[5], in which CD (2/19 cases) was also noted to be the major cause of retention. In another study with a total of 102 cases[9], the rate of retention was 13% (5/38) in patients with known CD, but only 1/64 cases with suspected CD had a retained capsule. The rate of capsule retention was very low in most studies, especially when the patients were selected without suspected small bowel obstruction or intestinal stricture. In the report of Barkin and Friedman[10], the incidence was 0.75% in a large study of 900 patients who had previously normal small intestines. Most recently, Li et al[7] have reported 14 cases of CE retention (1.4%) in 1000 capsule examinations. It was shown that tumors or NSAID strictures were the major etiology of retention in both of these studies. In our highly selected population, capsule retention occurred in 3 of 31 cases (two CD, one tumor).

Recently, dissolving patency capsules have been used in some studies to evaluate intestinal patency in patients with small bowel strictures, before video-CE (VCE). The patency capsule[11] is composed of lactose, remains intact in the gastrointestinal tract for 40-100 h post-ingestion, and disintegrates thereafter. Spada et al[12] have reported that 94% (30/34) of cases with small bowel stricture passed the intact or disintegrated capsule in the stools. Expulsion was confirmed in three cases by fluoroscopy, and the remaining patient withdrew consent to the study. In addition, VCE passed uneventfully through the small bowel stricture of all 10 patients who underwent VCE following patency capsule examination. The study of Spada et al has suggested that the patency capsule is a safe and effective tool for evaluation of functional patency of the small bowel, even when stricture has been indicated by traditional radiology. In another multicenter study[13], in all the 106 patients with strictures, no acute ileus was induced by Agile patency capsule. However, in the study of Bovin et al[14], in one of the 22 cases with suspected obstructive intestinal disease and/or radiological evidence of small-bowel strictures, impaction of an intact capsule led to ileus and emergency surgery. Similarly, in the study of Delvaux et al[15], of all 22 patients with known or suspected stenosis, the patency capsule induced a symptomatic intestinal occlusion in three patients, which was resolved spontaneously in one and required emergency surgery in two. It was shown that the start of dissolution at 40 h after ingestion was too late to prevent intestinal occlusion. Furthermore, the patency capsule can not detect stenosis and the etiology of small bowel obstruction.

Capsule retention has been defined as the presence of a capsule in the body for a minimum of 2 wk after ingestion, or when the capsule is retained in the bowel lumen indefinitely, unless targeted medical endoscopy or surgical intervention is initiated[16]. In our series, capsule retention occurred only in three cases, in which one of the capsules was spontaneously passed the stricture by medical treatment in 6 mo, and the other two retained capsules were retrieved at surgery. No acute small bowel obstruction occurred after administration of CE. The reported rate of acute abdomen induced by capsule is low. However, there is a controversy in the literature about the utility of capsule retention. In many studies, patients with a high risk of intestinal stricture were excluded for fear of capsule retention, which may have led to acute intestinal obstruction or surgical emergency. However, in most cases, capsule retention is symptomatic, although some patients accepted surgical therapy, which is safe and identifies or treats the underlying disease. Thus, some authors consider that capsule impaction is a valuable means of detecting significant stenosis that would benefit from surgical management[5]. In addition, the retained capsule can be retrieved using double-balloon endoscopy[1718]. Importantly, it is necessary to make the patients aware of the potential need for surgery before CE, although the risk for retention was low.

Based on our results, the most common etiology of small bowel obstruction was CD, followed by tumor. In our selected population, capsule retention was asymptomatic, which did not lead to surgical emergency. It is concluded that CE is a safe and effective tool for detecting etiology and stenosis of patients who have a history of small bowel obstruction, especially for the patients with suspected intestinal tumors or CD, which are not identified by routine examinations. Such results need future confirmation from prospective randomized studies.

Capsule endoscopy (CE) has been demonstrated to be superior to routine radiological examinations in the investigation of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding or suspected Crohn’s disease (CD). Small bowel obstruction or strictures are considered to be a contraindication for CE in many centers. However, the accuracy of radiography in this situation has often been questioned.

CE is now commonly performed for gastrointestinal bleeding of obscure origin or suspected CD. It is noted that the visualization of patients with suspected small bowel stenosis using traditional radiological methods is associated with high false-negative results and radiation doses. Recently, CE or patency capsule has been performed for suspected intestinal strictures in some studies, mainly for patients with known or suspected CD. However, reports about patients with subacute intestinal obstruction receiving CE are rare in the literature up till now.

At many centers, CE is considered to be contraindicated in suspected obstructive small bowel disease, for fear of capsule retention. In the present study, capsule retention occurred only in three cases (one of the capsules was spontaneously passed the stricture by medical treatment in 6 mo, the other two were retrieved at surgery), and no acute small bowel obstruction occurred after administration of CE. CE can be helpful in diagnosing subacute intestinal obstruction in patients with otherwise negative imaging studies, especially for patients with suspected intestinal tumors or CD.

CE is helpful in diagnosing subacute intestinal obstruction in patients with negative or uncertain imaging studies, which may become an appropriate indication for performing CE.

Subacute small bowel obstruction is diagnosed in patients who present with symptoms consistent with small bowel obstruction, in whom abdominal X-ray shows incomplete intestinal obstruction. CE is a novel diagnostic technique that has been used increasingly for analysis of many disorders of the small intestine, such as occult gastrointestinal bleeding, suspected CD, chronic diarrhea, and protein-losing enteropathy.

This paper describes CE in patients with small bowl obstruction. Although today the results of MRI of the intestine mostly offers the best chance of finding stenosis, CE is an interesting technique and should lead to a higher percentage of diagnosis.

| 1. | Saperas E, Dot J, Videla S, Alvarez-Castells A, Perez-Lafuente M, Armengol JR, Malagelada JR. Capsule endoscopy versus computed tomographic or standard angiography for the diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:731-737. |

| 2. | Mylonaki M, Fritscher-Ravens A, Swain P. Wireless capsule endoscopy: a comparison with push enteroscopy in patients with gastroscopy and colonoscopy negative gastrointestinal bleeding. Gut. 2003;52:1122-1126. |

| 3. | Ge ZZ, Hu YB, Xiao SD. Capsule endoscopy and push enteroscopy in the diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Chin Med J (Engl). 2004;117:1045-1049. |

| 4. | Hara AK, Leighton JA, Sharma VK, Fleischer DE. Small bowel: preliminary comparison of capsule endoscopy with barium study and CT. Radiology. 2004;230:260-265. |

| 5. | Cheifetz AS, Lewis BS. Capsule endoscopy retention: is it a complication? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:688-691. |

| 6. | Sears DM, Avots-Avotins A, Culp K, Gavin MW. Frequency and clinical outcome of capsule retention during capsule endoscopy for GI bleeding of obscure origin. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:822-827. |

| 7. | Li F, Gurudu SR, De Petris G, Sharma VK, Shiff AD, Heigh RI, Fleischer DE, Post J, Erickson P, Leighton JA. Retention of the capsule endoscope: a single-center experience of 1000 capsule endoscopy procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:174-180. |

| 8. | Mason M, Swain J, Matthews BD, Harold KL. Use of video capsule endoscopy in the setting of recurrent subacute small-bowel obstruction. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2008;18:713-716. |

| 9. | Cheifetz AS, Kornbluth AA, Legnani P, Schmelkin I, Brown A, Lichtiger S, Lewis BS. The risk of retention of the capsule endoscope in patients with known or suspected Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2218-2222. |

| 10. | Barkin JS, Friedman S. Wireless capsule endoscopy requiring surgical intervention: the world’s experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:S298. |

| 11. | Cheifetz SA, Sachar D, Lewis B. Small bowel obstruction: indication or contraindication for capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:AB461. |

| 12. | Spada C, Spera G, Riccioni M, Biancone L, Petruzziello L, Tringali A, Familiari P, Marchese M, Onder G, Mutignani M. A novel diagnostic tool for detecting functional patency of the small bowel: the Given patency capsule. Endoscopy. 2005;37:793-800. |

| 13. | Herrerias JM, Leighton JA, Costamagna G, Infantolino A, Eliakim R, Fischer D, Rubin DT, Manten HD, Scapa E, Morgan DR. Agile patency system eliminates risk of capsule retention in patients with known intestinal strictures who undergo capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:902-909. |

| 14. | Boivin ML, Lochs H, Voderholzer WA. Does passage of a patency capsule indicate small-bowel patency? A prospective clinical trial? Endoscopy. 2005;37:808-815. |

| 15. | Delvaux M, Ben Soussan E, Laurent V, Lerebours E, Gay G. Clinical evaluation of the use of the M2A patency capsule system before a capsule endoscopy procedure, in patients with known or suspected intestinal stenosis. Endoscopy. 2005;37:801-807. |

| 16. | Cave D, Legnani P, de Franchis R, Lewis BS. ICCE consensus for capsule retention. Endoscopy. 2005;37:1065-1067. |

| 17. | Tanaka S, Mitsui K, Shirakawa K, Tatsuguchi A, Nakamura T, Hayashi Y, Sakamoto C, Terano A. Successful retrieval of video capsule endoscopy retained at ileal stenosis of Crohn's disease using double-balloon endoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:922-923. |