Published online May 21, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2340

Revised: April 13, 2009

Accepted: April 20, 2009

Published online: May 21, 2009

AIM: To compare the performance of different types of abdominal drains used in bariatric surgery.

METHODS: A vertical banded Roux-en-Y gastric bypass was performed in 33 morbidly obese patients. Drainage of the peritoneal cavity was performed in each case using three different types of drain selected in a randomized manner: a latex tubular drain, a Watterman tubulolaminar drain, and a silicone channeled drain. Drain permeability, contamination of the drained fluid, ease of handling, and patient discomfort were evaluated postoperatively over a period of 7 d.

RESULTS: The patients with the silicone channeled drain had larger volumes of drainage compared to patients with tubular and tubulolaminar drains between the third and seventh postoperative days. In addition, a lower incidence of discomfort and of contamination with bacteria of a more pathogenic profile was observed in the patients with the silicone channeled drain.

CONCLUSION: The silicone channeled drain was more comfortable and had less chance of occlusion, which is important in the detection of delayed dehiscence.

- Citation: Salgado Júnior W, Macedo Neto MM, dos Santos JS, Sakarankutty AK, Ceneviva R, de Castro e Silva Jr O. Study of the patency of different peritoneal drains used prophylactically in bariatric surgery. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(19): 2340-2344

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i19/2340.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.2340

Most of the immediate complications occurring after bariatric surgery are due to technical errors that may go unrecognized[1]. Among them, intraoperative bleeding and dehiscence of anastomoses, although infrequent, are the most feared complications. Dehiscence occurs at a frequency of 1% to 4.4% of cases, resulting in significant morbidity and eventually even death. The early detection of this complication could reduce morbidity and mortality[2–4].

Resources for the early diagnosis of dehiscence during the postoperative period are limited. The clinical signs and symptoms are difficult to interpret and imaging exams, when they can be performed, may yield false results due to excess body weight.

Over the last three decades, efforts have been made to investigate the effectiveness of prophylactic drainage of the peritoneal cavity in controlled randomized clinical trials[5–8]. Although there are no evidence-based data justifying the use of drains in various situations, including bariatric surgery, most services routinely use them for the early identification of fistulae and their treatment[9].

Different types of drains are available but the search is ongoing for the ideal model. A closed-system model of a silicone drain was recently produced, with multiple channels in its intra-abdominal portion and vacuum aspiration (Blake®-Ethicon), which has been used in various operations including bariatric surgery[10–16].

The objective of the present study was to assess the patency of three different types of abdominal drains used in bariatric surgery.

During the period from January to September 2007, 33 morbidly obese patients were selected for surgical treatment by banded Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. The patients were divided into three groups according to the type of drain employed in the peritoneal cavity. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the hospital and all patients gave written informed consent to participate.

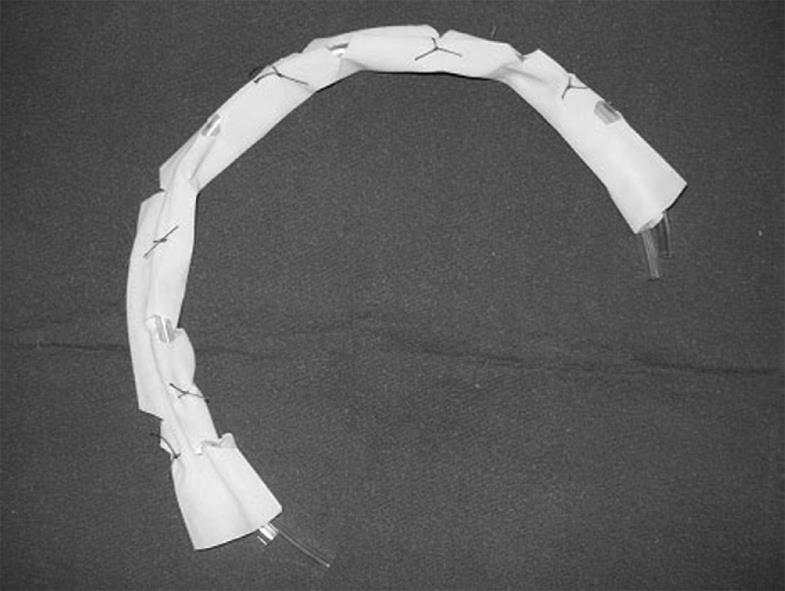

The type of drain used was selected at random: Group 1, closed-system latex tubular drain with multiple holes and without aspiration; Group 2, Watterman drain consisting of two No. 16 Levin catheters with multiple holes wrapped with a No. 4 Penrose tube (open system) (Figure 1); Group 3, silicone drain with multiple channels (Blake®Ethicon) 24 Fr connected to a 300 mL J-Vac® reservoir (Ethicon) under continuous vacuum. All drains were left in place for seven days after surgery.

Before removal of the drain, the patient received 120 mL of a methylene blue solution by the oral route in order to test for the presence of possible anastomosis dehiscence of staple lines. No radiological test was applied. For the evaluation of drain permeability, the daily output of each drain was recorded over a postoperative period of seven days.

Microbiological and antimicrobial analysis of the intraperitoneal end of the drains was performed on the seventh postoperative day during the interruption of drainage. In order to obtain peritoneal fluid the drains were punctured in their external portion. The end of each drain located in the peritoneal cavity was also sent for analysis. Both procedures were carried out under rigorous asepsis.

Subjective evaluation of the comfort of each drain was performed using a questionnaire which was completed by the patient on the day of drain removal. The information obtained referred to pain at the drain site and to pain during drain removal (graded from 0 to 5), ease of handling and discomfort with the presence of odors.

Groups were compared by one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and then paired for application of the Tukey post-test. The level of significance was set at 5%.

All patients who underwent surgery were evaluated. Mean patient age, weight and BMI were 37.1 years, 138.20 kg and 51.42 kg/m2, respectively. The characteristics of the groups studied were similar (Table 1).

| Group 1-Latex | Group 2-Watterman | Group 3-Blake | |

| Age (yr) | 35.45 ± 7.56 | 36.18 ± 10.68 | 39.81 ± 9.52 |

| Gender: M/F | 3/8 | 3/8 | 1/10 |

| Weight (kg) | 138.48 ± 17.58 | 135.98 ± 19.86 | 140.30 ± 24.58 |

All patients had a favorable postoperative course without major complications. There was no extravasation of methylene blue during the tests carried out on the seventh postoperative day. However, the intraperitoneal end of the Watterman drain in a group 2 patient was stained blue at the time of removal. A No. 16 Levin catheter was immediately introduced in this patient in order to maintain patency. No significant drainage occurred on subsequent days and the patient’s course was favorable.

No difference in collected fluid volume was observed up to the second postoperative day. Starting on the third day, the silicone channeled drain showed significantly greater drainage compared to the others (Table 2) and this difference persisted up to the 7th postoperative day. No difference in collected volume was observed between the tubular latex drain and the tubulolaminar (Watterman) drain (Table 3).

| Postoperative days | Group 1 Latex | Group 2 Watterman | Group 3 Blake | P |

| Day 1 | 146 ± 57.5 | 190 ± 178.6 | 150 ± 79 | 0.656 |

| Day 2 | 89 ± 74.1 | 96.7 ± 68.8 | 168.2 ± 107.6 | 0.091 |

| Day 3 | 29.4 ± 27.7 | 57.3 ± 53 | 107.5 ± 79.2 | 0.016 |

| Day 4 | 25.3 ± 16.6 | 34.8 ± 39.3 | 106.2 ± 106.5 | 0.021 |

| Day 5 | 28.3 ± 40.7 | 34.1 ± 30.4 | 123.5 ± 105.3 | 0.005 |

| Day 6 | 26.8 ± 40.6 | 21.3 ± 17 | 88.5 ± 51.8 | 0.001 |

| Day 7 | 26.9 ± 36 | 19.5 ± 18.6 | 89.7 ± 76 | 0.007 |

| Postoperative days | Blake vs Watterman | Blake vs Latex | Latex vs Watterman |

| Day 1 | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 |

| Day 2 | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 |

| Day 3 | P > 0.05 | P < 0.05 | P > 0.05 |

| Day 4 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | P > 0.05 |

| Day 5 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | P > 0.05 |

| Day 6 | P < 0.01 | P < 0.01 | P > 0.05 |

| Day 7 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | P > 0.05 |

Microbiological evaluation of the fluid from the peritoneal cavity collected through the various drains revealed that nine patients with the silicone channel drain had a positive culture, with the bacteria most frequently detected being Staphylococcus spp., Proteus spp. and Klebsiella spp.; for the latex tubular drain all cultures were positive and the most frequent bacteria were Enterobacter spp., Enterococcus spp., Proteus spp. and Pseudomonas spp.; all the cultures of the tubulolaminar Watterman drains were also positive and the most frequent bacteria were Serratia spp., Morganella spp., Proteus spp. and Enterobacter spp..

Microbiological evaluation of the drain end located in the peritoneal cavity showed a similar frequency of culture positivity and similar bacterial species identified in the peritoneal fluid for all drains (Table 4).

| Group 1-Latex | Group 2-Watterman | Group 3-Blake | |

| Patient 1 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Enterobacter cloacae1 | Staphylococcus aureus |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Escherichia coli1 | Staphylococcus aureus | |

| Patient 2 | Enterobacter aerogenes | Proteus mirabilis | Proteus mirabilis |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | Proteus mirabilis | Pseudomonas aeruginosa + Morganella morgani | |

| Patient 3 | Klebsiella pneumoniae + Staphylococcus simulans | Serratia marcescens | Staphylococcus aureus + Proteus mirabilis + Enterobacter cloacae |

| Staphylococcus aureus + Klebsiella pneumoniae + Morganella morgani + Proteus mirabilis | Serratia marcescens | Serratia marcescens + Enterococcus faecalis | |

| Patient 4 | Serratia marcescens | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Proteus mirabilis + Klebsiella pneumoniae + Enterococcus faecalis |

| Serratia marcescens | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Staphylococcus aureus + Proteus mirabilis | |

| Patient 5 | Escherichia coli + Proteus mirabilis | Enterobacter cloacae | Proteus mirabilis |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Proteus mirabilis | |

| Patient 6 | Citrobacter koseri | Proteus vulgaris | Klebsiella pneumoniae + Proteus mirabilis |

| Proteus mirabilis + Citrobacter koseri | Proteus vulgaris | Klebsiella pneumoniae + Proteus mirabilis | |

| Patient 7 | Staphylococcus aureus + Proteus mirabilis | Pseudomonas aeruginosa + Klebsiella pneumoniae | - |

| Staphylococcus aureus + Proteus mirabilis | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | - | |

| Patient 8 | Proteus mirabilis | Enterococcus faecalis + Staphylococcus aureus | - |

| Proteus mirabilis + Serratia marcescens | Enterococcus faecalis + Staphylococcus aureus | - | |

| Patient 9 | Enterobacter cloacae | Escherichia coli | Staphylococcus epidermidis |

| Enterobacter cloacae | Escherichia coli | Staphylococcus aureus | |

| Patient 10 | Escherichia coli + Enterococcus faecalis | Enterococcus faecalis | Staphylococcus simulans |

| Morganella morganii | Enterococcus faecalis | Klebsiella pneumoniae | |

| Patient 11 | Enterobacter cloacae | Proteus mirabilis + Kebsiella pneumoniae | Staphylococcus epidermidis |

| Enterobacter cloacae | Proteus mirabilis | Staphylococcus epidermidis |

Drain handling and emptying of the collecting bag were considered easy for all drain types. The tubular latex drain was considered to be the most painful and the silicone channeled drain was considered to present fewer unpleasant odors (Table 5).

| Blake | Watterman | Latex | |

| Ease of emptying the collecting bag | |||

| Very easy | 7 | 7 | 9 |

| Easy | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| Difficult | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Very difficult | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Odor during the dressings | |||

| None | 9 | 1 | 5 |

| Bad | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Very bad | 0 | 7 | 3 |

| Pain at the drain site (pain scale) | |||

| 0 (no pain) | 6 | 5 | 2 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 5 (very intense pain) | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Pain during drain removal (pain scale) | |||

| 0 (no pain) | 7 | 4 | 3 |

| 1 | 2 | 6 | 2 |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 5 (very intense pain) | 0 | 0 | 2 |

Drainage of body cavities has been practiced in medicine for a long time. During the last three decades, surgeons have made efforts to investigate the value of prophylactic drainage after abdominal surgery in controlled randomized clinical trials[89]. The utility of closed suction drains after gastrointestinal procedures has long been debated. Although there is some data against the use of prophylactic drains, bariatric surgeons often use them for a variety of reasons: as an early alert to the presence of leakage and hemorrhage, and as a resource for the treatment of these complications[16].

It was not the subject of this work to study the benefits or disadvantages of the presence of drains or how often they are used. For this type of study, a greater number of patients must be evaluated. Although there is a lack of consensus regarding prophylactic drainage in gastric surgery[9], at our institution, we always use tubular closed drains without suction in gastrointestinal procedures and, in accordance with many bariatric centers, prophylactic drains are routinely used in bariatric surgery. On the other hand, the effectiveness of a tubular closed drain without suction is very low for prolonged postoperative periods and may impair the diagnosis and treatment of fistulae after bariatric surgery, especially those with delayed occurrence[5]. In an experimental study, the tubular drain was found to be obstructed early, 24 to 48 h after its introduction, due to envelopment by the omentum and penetration of omental fringes into the draining orifices. Contamination around the drain has also been observed, causing washing for relief of obstruction to be risky[6].

Early studies have demonstrated that the persistence of serous drainage after obstruction of drains placed in the peritoneal cavity originates from a reaction by the organism to the presence of a foreign body, in this case the drain itself[7]. The migration of bacteria into the peritoneal cavity through the drain has also been reported[67].

In general, tubular closed drains tend to result in lower infection rates compared to laminar open catheters. On the other hand, laminar open drains are less frequently obstructed[11]. Thus, it is pertinent to look for an alternative way of keeping drains permeable for a prolonged period of time in order to facilitate the diagnosis and management of fistulae after bariatric surgery, especially those occurring in a delayed manner.

In the present study, the performance of the latex tubular drain without suction was similar to that of the Watterman model, which functions as a tubulolaminar drain, also without suction. There was no difference in terms of drained volume, culture positivity or diversity of the bacterial species isolated. Subjective evaluation revealed that the tubulolaminar drain had an unpleasant odor when dressings were changed compared with the tubular drain, which was more painful when handled.

The silicone channeled closed drain with vacuum and without multiple perforations had some advantages over the two more traditional models, such as a lower incidence of obstruction and pain at the site of insertion, as well as easy handling, and represents a more recent alternative that deserves to be evaluated in view of the additional costs[12].

In the present study, a persistently greater volume of daily drainage was observed with the silicone channeled closed drain, suggesting lower obstruction rates. A lower incidence of pain and fewer unpleasant odors were also recorded. Bacterial contamination by the retrograde route occurred in 81% of cases, however, the bacteria most frequently identified had a less pathogenic profile compared to the other two types of drain.

Thus, we can conclude that the silicone drain with multiple channels has a more prolonged permeability, and is recommended as an alternative for drainage of the peritoneal cavity after bariatric surgery. This recommendation is made in view of the fact that dehiscence can manifest in a delayed manner, as we experienced a patient with staple line dehiscence on the seventh postoperative day.

With the current increase in bariatric surgery, some complications such as, intraoperative bleeding and dehiscence of anastomoses, although infrequent, are matters of concern. The resources for the early diagnosis of these complications are limited. Drainage of the peritoneal cavity may result in the early identification and treatment of fistulae. Different types of drains are available but the search is ongoing for the ideal model.

A closed-system model of a silicone drain, with multiple channels in its intra-abdominal portion (Blake®Ethicon) was recently produced. This silicone channeled closed drain with vacuum had some advantages over the two more traditional models, such as a lower incidence of obstruction and pain at the site of insertion, as well as easy handling.

This silicone drain (Blake®Ethicon) is being used by a great number of surgeons around the world and for a wide variety of surgical procedures such as cardiothoracic surgery, transplantation and bariatric surgery

This study suggests that the silicone drain is a good alternative for drainage of the peritoneal cavity after bariatric surgery, if the surgeon decides to drain it.

Bariatric surgery is carried out in severely obese patients with the objective of reducing body weight and the comorbidity related to obesity. Dehiscence is any rupture or opening of surgical sutures. Drains are a device by which a channel or open area may be established for the exit of fluids or purulent material from a cavity, wound, or infected area.

The authors compared the performance of different types of abdominal drains used during bariatric surgery. This article is interesting and well written.

| 1. | Serafini F, Anderson W, Ghassemi P, Poklepovic J, Murr MM. The utility of contrast studies and drains in the management of patients after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2002;12:34-38. |

| 2. | Ovnat A, Peiser J, Solomon H, Charuzi I. Early detection and treatment of a leaking gastrojejunostomy following gastric bypass. Isr J Med Sci. 1986;22:556-558. |

| 3. | Sims TL, Mullican MA, Hamilton EC, Provost DA, Jones DB. Routine upper gastrointestinal Gastrografin swallow after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2003;13:66-72. |

| 4. | Schauer PR, Ikramuddin S, Gourash W, Ramanathan R, Luketich J. Outcomes after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2000;232:515-529. |

| 6. | Agrama HM, Blackwood JM, Brown CS, Machiedo GW, Rush BF. Functional longevity of intraperioneal drains: an experimental evaluation. Am J Surg. 1976;132:418-421. |

| 7. | Yates JL. An experimental study of the local effects of peritoneal drainage. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1905;1:473-492. |

| 9. | Petrowsky H, Demartines N, Rousson V, Clavien PA. Evidence-based value of prophylactic drainage in gastrointestinal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Ann Surg. 2004;240:1074-1084; discussion 1084-1085. |

| 10. | Ernst R, Wiemer C, Rembs E, Friemann J, Theile A, Schäfer K, Zumtobel V. [Local effects and changes in wound drainage in the free peritoneal cavity]. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1997;382:380-392. |

| 11. | Raves JJ, Slifkin M, Diamond DL. A bacteriologic study comparing closed suction and simple conduit drainage. Am J Surg. 1984;148:618-620. |

| 12. | Gundry SR, Shattuck OH, Razzouk AJ, del Rio MJ, Sardari FF, Bailey LL. Facile minimally invasive cardiac surgery via ministernotomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65:1100-1104. |

| 13. | Angelini GD, Penny WJ, el-Ghamary F, West RR, Butchart EG, Armistead SH, Breckenridge IM, Henderson AH. The incidence and significance of early pericardial effusion after open heart surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1987;1:165-168. |

| 14. | Porter KA, O'Connor S, Rimm E, Lopez M. Electrocautery as a factor in seroma formation following mastectomy. Am J Surg. 1998;176:8-11. |

| 15. | Mehran A, Szomstein S, Zundel N, Rosenthal R. Management of acute bleeding after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2003;13:842-847. |

| 16. | Dallal RM, Bailey L, Nahmias N. Back to basics--clinical diagnosis in bariatric surgery. Routine drains and upper GI series are unnecessary. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2268-2271. |