CASE REPORT

A 49-year-old black man presented with acute renal failure with a serum creatinine of 13 mg/dL. He was found to have circulating plasma cells in the blood and was diagnosed with kappa light chain MM by a bone marrow biopsy, which revealed 90% plasma cells with kappa light chain restriction. Free kappa light chains were noted in the serum. Cytogenetics of the bone marrow plasma cells revealed an abnormal hypodiploid clone with deletions of chromosomes 4, 13, 16, 17 and 21. A skeletal survey was negative for lytic bone lesions. The serum hemoglobin was 10 g/dL and the serum calcium was normal. Liver enzymes were normal at presentation. The physical examination was remarkable only for cachexia. Therapy with thalidomide (200 mg/d) and high dose dexamethasone (40 mg on days 1-4, 7-11, 14-17 and 21-24) was initiated. After receiving three cycles over a 3-mo period, the patient had clearance of circulating plasma cells on the peripheral blood smear but no response on repeat bone marrow biopsy. His therapy was switched to bortezomib.

One month after the initiation of thalidomide and dexamethasone, he started developing a gradual increase in total and direct bilirubin from a normal baseline. Right-upper-quadrant ultrasound revealed an enlarged liver with a largest dimension of 23 cm; however, no mass lesions were noted. The parenchymal echogenecity was within normal limits. Abdominal computed tomography performed with oral and IV contrast agents revealed a diffusely enlarged liver with no mass lesions and no evidence of intra- or extrahepatic ductal dilatation. After three cycles of thalidomide and dexamethasone therapy, the total bilirubin had increased to 3.9 mg/dL.

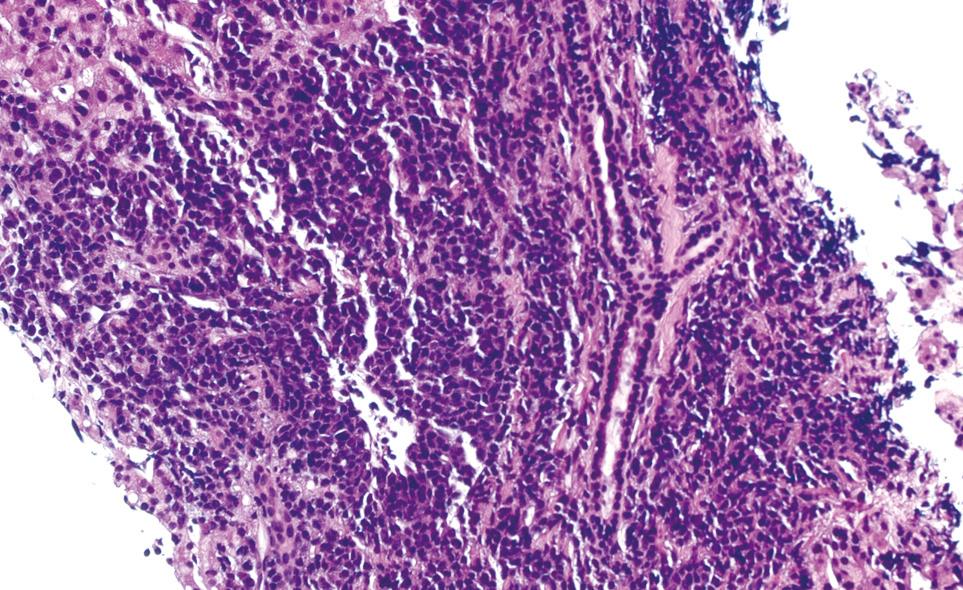

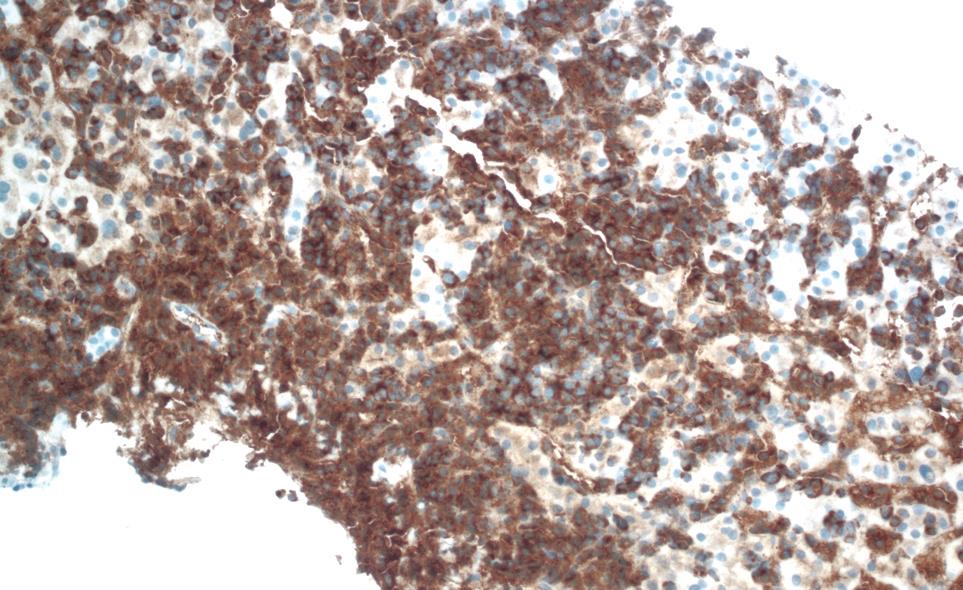

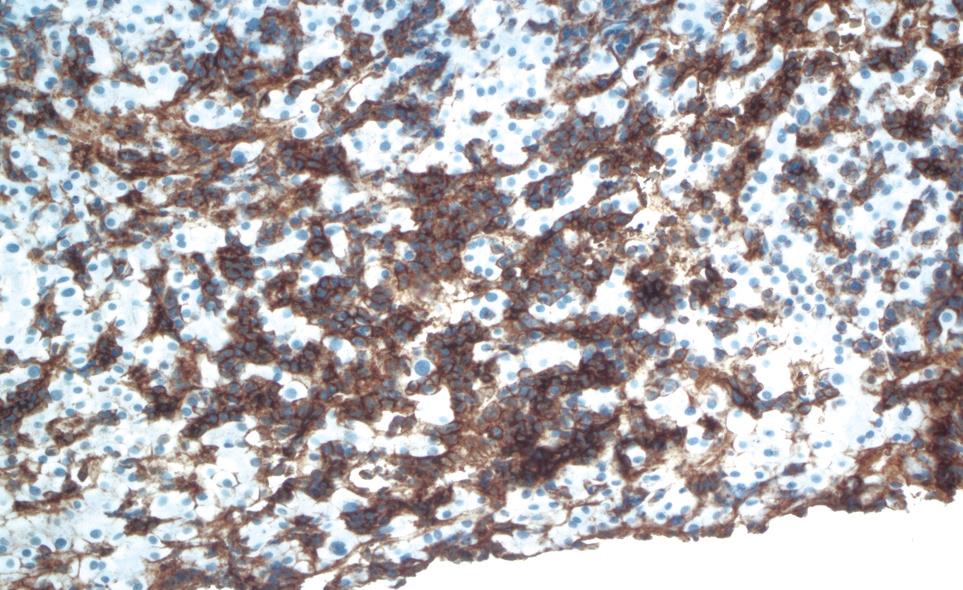

One week after switching to bortezomib, the patient was admitted to the hospital for further evaluation after the total bilirubin acutely increased to 9.4 mg/dL. The remainder of the liver function tests revealed aspartate aminotransferase of 41 U/L, alanine aminotransferase of 38 IU/L, lactate dehydrogenase of 306 IU/L, and gamma-glutamyltransferase of 286 IU/L. The direct bilirubin was 5.8 mg/dL. The physical examination was remarkable for frank jaundice and hepatomegaly. A repeat ultrasound of the abdomen showed significant liver enlargement up to 26 cm over a period of 2 mo with no evidence of biliary obstruction. A hepatobiliary imino-diacetic acid scan revealed delayed hepatic uptake consistent with severe hepatocellular dysfunction. Hepatitis serology for hepatitis A/B/C, and antinuclear and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies was negative. Cytomegalovirus serology was also negative. A transjugular liver biopsy was performed to rule out drug toxicity. It demonstrated massive infiltration of the liver parenchyma with plasma cells (Figure 1). The immunological profile of the liver biopsy revealed diffuse kappa light chain restriction that was similar to that in the bone marrow biopsy, which supported the diagnosis of MM with hepatic infiltration (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Flow cytometry of the liver biopsy revealed plasma cells with CD38/CD138 co-expression and kappa light chain restriction. No evidence of amyloidosis was evident on immunostaining. During his 2 wk of hospitalization, the patient rapidly developed hepatic failure, characterized by coagulopathy, hyperbilirubinemia, encephalopathy and ascites. He was discharged to hospice care and expired 1 wk later.

Figure 1 HE liver biopsy showing massive plasma cell infiltration (HE).

Figure 2 Positive kappa light chain stain on liver biopsy.

Figure 3 Positive CD138 (syndecan-1), a plasma cell marker.

CD138 is expressed on plasma cells, including the malignant plasma cells of MM and some lymphomas.

DISCUSSION

Pathologic liver involvement in patients with MM has been reported in up to 45% of patients[12]. An autopsy series of 128 cases with MM done by Perez-Soler et al[3] showed diffuse infiltration of the liver by plasma cells in 10 of 21 patients with liver tissue involvement. Thomas et al[4] reviewed 64 cases of MM, including autopsy reports and prior medical records; 58% of patients had hepatomegaly, defined as percussible dullness of more than 12 cm or a liver edge palpable 4 cm below the right costal margin, and 25% had splenomegaly. Jaundice was reported in nine patients (14%) and serum bilirubin values ranged from 3.2 to 17.3 mg/dL. Only six patients (9%) had a completely normal liver on pathological examination, while 40% had plasma cell involvement of the liver in the form of plasmacytoma or diffuse sinusoidal infiltration. Both these two autopsy series excluded cases with plasma cell leukemia[34].

The histological pattern of liver involvement in MM can be in the form of light chain deposition disease, extramedullary plasmacytoma, amyloidosis, or a diffuse infiltrative pattern. Massive liver involvement can be either from tumor-forming plasmacytomas or diffuse sinusoidal flooding[4]. The latter can consist of sinusoidal flooding by plasma cells of varying degrees of differentiation with little or no propensity to destroy liver parenchyma[5]. Some of these patients may present with non-obstructive jaundice and show elevations in alkaline phosphatase from plasma cell infiltration, as did our patient[3]. Only two prior cases of severe cholestasis associated with hepatic failure have been reported[67]. Radiographic imaging is unable to detect this diffuse infiltrative pattern and a liver biopsy is essential to make a diagnosis.

Plasmacytomas (nodular forming pathology) are less common. This entity can be detected radiographically as space-occupying lesions in the liver or in the head of the pancreas, and may be associated with biliary obstruction[8–10].

Amyloidosis manifested as tissue deposition of clonal light-chain fibrils is seen in 15% of the general MM patient population. Liver involvement has been reported in MM patients as well as those with primary systemic amyloidosis[11]. Elevation in alkaline phosphatase is more common and liver enzymes are often normal or mildly elevated. Obstructive jaundice occurs rarely and only a few cases have been reported, with some associated with hepatic failure[12–18].

The clinical significance of liver involvement in MM is uncertain. Treatment of MM with hepatic involvement requires systemic therapy. Successful treatment with combination chemotherapy or steroids alone has been reported[61920]. Talamo et al[21] have reviewed the medical records of 24 patients with MM involvement of the gastrointestinal (GI) system as documented by tissue biopsy, 11 of whom had hepatic involvement. GI involvement at the time of initial diagnosis of MM was less common than later in the disease course.

The treatment of MM patients with significant liver dysfunction is challenging because of the inability to deliver most chemotherapeutic agents in the setting of liver failure. Substantial dose reductions are required to administer anthracyclines and vincristine in the setting of liver failure. Steroids, and the newer agents thalidomide and bortezomib have been administered in these settings, although thalidomide has been cited in a single case report as causing fulminant hepatic dysfunction, and liver toxicity has been reported rarely with bortezomib[2223].

Stem cell transplantation (SCT) is now the standard first-line therapy for myeloma patients who respond to chemotherapy. Patients are analyzed to evaluate the role of treatment with high-dose chemotherapy with autologous or allogeneic SCT, and its impact on survival[21]. It has been found that GI involvement is common during relapse after SCT. Plasmablastic morphology was common (Bartl grade III) in 29% of cases with GI involvement. Monosomy 13, which is one of the most powerful negative prognostic factors, was observed in 46% of the cases, while it is present in 15% of the general MM patient population. SCT is effective in inducing remissions but relapse is common.

In conclusion, there are no classical clinical manifestations of liver infiltration in MM. The initial presentation can be subtle, but then very rapidly progressive, as in our case. The number of clinically reported cases of liver involvement with MM is small, therefore, it is difficult to ascertain the prognosis of this clinical presentation of the disease or its response to therapy. We suspect that the prognosis is poor because of the limited number of chemotherapeutic agents that can be administered to patients with severe liver dysfunction. The optimal approach in managing these cases can only be standardized after studying a larger number of patients.