Published online Apr 28, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1985

Revised: March 23, 2009

Accepted: March 30, 2009

Published online: April 28, 2009

AIM: To evaluate 20 adults with intussusception and to clarify the cause, clinical features, diagnosis, and management of this uncommon entity.

METHODS: A retrospective review of patients aged > 18 years with a diagnosis of intestinal intussusception between 2000 and 2008. Patients with rectal prolapse, prolapse of or around an ostomy and gastroenterostomy intussusception were excluded.

RESULTS: There were 20 cases of adult intussusception. Mean age was 47.7 years. Abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting were the most common symptoms. The majority of intussusceptions were in the small intestine (85%). There were three (15%) cases of colonic intussusception. Enteric intussusception consisted of five jejunojejunal cases, nine ileoileal, and four cases of ileocecal invagination. Among enteric intussusceptions, 14 were secondary to a benign process, and in one of these, the malignant cause was secondary to metastatic lung adenocarcinoma. All colonic lesions were malignant. All cases were treated surgically.

CONCLUSION: Adult intussusception is an unusual and challenging condition and is a preoperative diagnostic problem. Treatment usually requires resection of the involved bowel segment. Reduction can be attempted in small-bowel intussusception if the segment involved is viable or malignancy is not suspected; however, a more careful approach is recommended in colonic intussusception because of a significantly higher coexistence of malignancy.

- Citation: Yakan S, Calıskan C, Makay O, Deneclı AG, Korkut MA. Intussusception in adults: Clinical characteristics, diagnosis and operative strategies. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(16): 1985-1989

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i16/1985.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.1985

Intestinal invagination or intussusception is the leading cause of intestinal obstruction in children, but in adults it accounts for only 5% of all intussusceptions, and 0.003%-0.02% of all adult hospital admissions. In contrast to childhood intussusception, which is idiopathic in 90% of cases, adult intussusception has a demonstrable lead point, which is a well-definable pathological abnormality in 70%-90% of cases[1–3].

The presentation of pediatric intussusception often is acute with sudden onset of intermittent colicky pain, vomiting, and bloody mucoid stools, and the presence of a palpable mass. In contrast, the adult entity may present with acute, subacute, or chronic non-specific symptoms[4]. Therefore, the initial diagnosis often is missed or delayed and may only be established when the patient is on the operating table. Most surgeons accept that adult intussusception requires surgical resection because the majority of patients have intraluminal lesions. However, the extent of resection and whether the intussusception should be reduced remains controversial[5].

Therefore in this paper, we report our experience in an attempt to clarify the cause, clinical features, diagnosis, and management of this uncommon entity.

The clinical, operative, and pathological records of 20 adult patients (> 18 years of age) with a diagnosis of intussusception, surgically treated between 2000 and 2008 were reviewed retrospectively. Patients with rectal prolapse, prolapse of or around an ostomy and gastroenterostomy intussusception were excluded.

Intussusception was classified as enteric or colonic. When the pathologic lead point was located in the small bowel, including jejunojejunal, ileoileal and ileocolic intussuceptions, it was classified as enteric. Colonic intussusception included ileocecal-colic, colocolonic, sigmoidorectal, and appendicocecal intussusception. Ileocolic and ileocecal-colic intussusception was distinguished by the site of the pathological lead point. When the lead point was at the ileum, intussusception was classified as ileocolic, whereas when the lead point was at the ileocecal valve, it was classified as ileocecal-colic.

A total of 20 patients were identified who had a diagnosis of intussusception and were older than 18 years of age. The average age of the patients was 47.7 years, with a range of 21 to 75 years. Nine (45%) were male and 11 (55%) were female.

Pain was the most common presenting complaint and was present in 17 patients (85%). Nausea, vomiting, constipation, rectal bleeding, and diarrhea were other symptoms. Table 1 shows the symtoms and signs. A palpable mass was found in only one patient (5%). The mean duration of symptoms was 7.9 d (range, 1 d to 3 mo). Six patients (30%) had acute symptoms (< 4 d), five (25%) had subacute symptoms (4-14 d), and nine (45%) had chronic symptoms (> 14 d).

| Symptoms and signs | n (%) |

| Pain | 17 (85) |

| Nausea | 15 (75) |

| Vomiting | 14 (70) |

| Constipation | 3 (15) |

| Rectal bleeding | 1 (5) |

| Diarrhea | 1 (5) |

| Abdominal mass | 1 (5) |

| Fever | 1 (5) |

Plain abdominal X-rays were first obtained in patients with acute symptoms, which revealed air-fluid levels that suggested intestinal obstruction in five patients (25%). It was normal in the other 15 patients (75%).

Intussusception was a preoperative diagnosis in 14 patients (70%). Six patients (30%) who were diagnosed with intussusception in the operating room showed serious signs of bowel strangulation and were not diagnosed preoperatively because they were transferred to the operating room without further radiological evaluation. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan was performed in 12 patients, of whom 10 (83.3%) were diagnosed with intussusception. The finding on CT was an in-homogeneous soft-tissue mass that was target- or sausage-shaped (Figure 1). Three patients underwent colonoscopy, and intussusception was confirmed in two. A small-bowel series were performed in three patients. Two patients in diagnostic studies had findings suspicious of intussusception caused by obstruction with polyps or tumors.

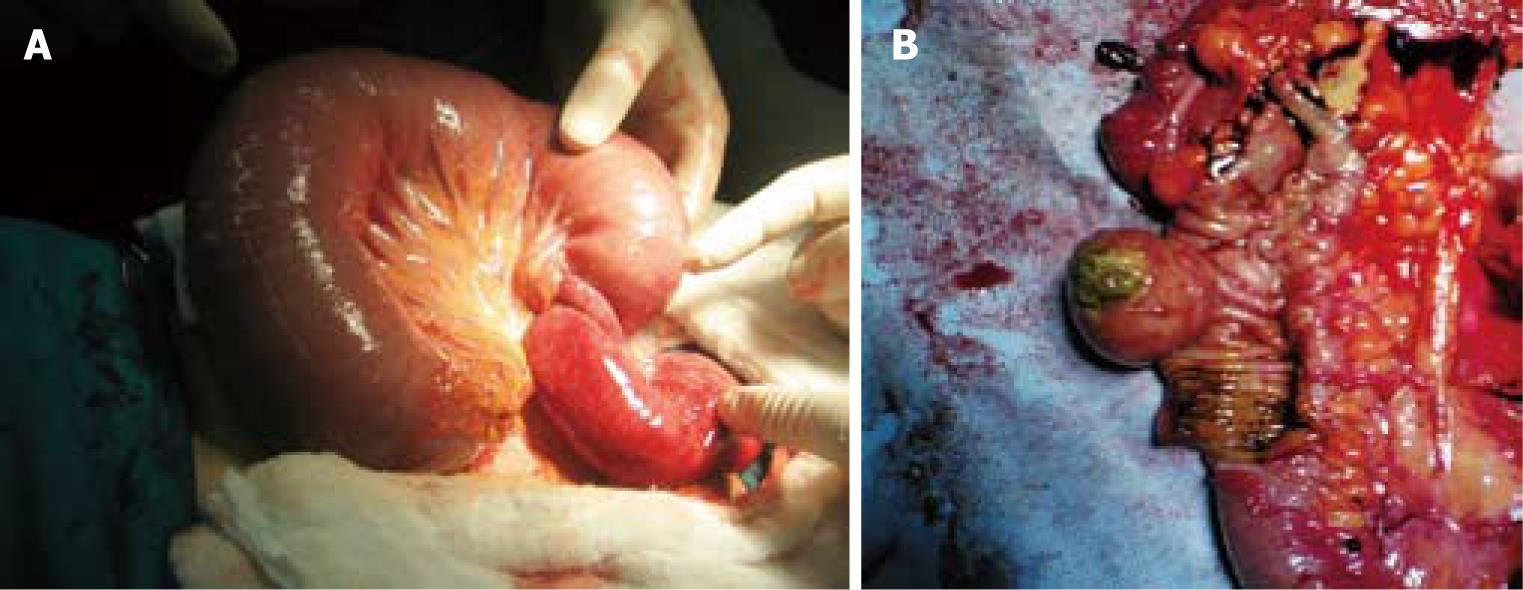

The majority of intussusceptions were enteric (17/20 or 85%) (Table 2). There were three (15%) cases of colonic intussusception. Five cases of enteric intussusception were jejunojejunal (Figure 2A), nine were ileoileal, and four had ileocecal invagination detected.

| No. of patients | Age | Gender | Location of the lesion | Preoperative diagnosis | Surgical treatment | Pathology |

| 1 | 33 | M | Enteric (jejunojejunal) | + (small bowel series) | Reduction + enterotomy + polypectomy | Peutz-Jeghers (hamartomatous polyp) |

| 2 | 49 | F | Enteric (ileocecal) | + (CT) | Right hemicolectomy | Ileal lipoma |

| 3 | 60 | F | Enteric (ileoileal) | - (Urgent) | Reduction + segmental ileal resection | Inflammatory fibroid polyp |

| 4 | 30 | F | Enteric (ileocecal) | + (CT) | Reduction + segmental ileal resection | Fibrous polyp |

| 5 | 63 | M | Colonic (colocolic) | + (colonoscopy) | Near totalcolectomy + ileorectal anastomosis | Lenfoma |

| 6 | 56 | F | Enteric (ileocecal) | + (CT) | Right hemicolectomy | Inflammatory fibroid polyp |

| 7 | 21 | F | Enteric (jejunojejunal) | + (CT) | Reduction + segmental jejunal resection + enterotomy + polypectomy | Peutz-Jeghers (hamartomatous polyp) |

| 8 | 36 | M | Enteric (ileoileal) | - (Urgent) | Reduction | Idiopathic |

| 9 | 75 | M | Colonic (colocolic) | + (colonoscopy) | Left hemicolectomy | Adeno CA |

| 10 | 25 | M | Enteric (ileoileal) | - (Urgent) | Reduction | Congenital band |

| 11 | 60 | M | Enteric (ileoileal) | + (CT) | Reduction + segmental ileal resection | Ileal lipoma |

| 12 | 28 | F | Enteric (jejunojejunal) | - (Urgent) | Reduction + segmental jejunal resection | Inflammatory fibroid polyp |

| 13 | 48 | M | Enteric (jejunojejunal) | + (CT) | Reduction + segmental jejunal resection | Idiopathic |

| 14 | 55 | F | Enteric (ileoileal) | + (CT) | Reduction + segmental ileal resection | Ileal lipoma |

| 15 | 62 | F | Enteric (ileoileal) | + (CT) | Reduction + segmental ileal resection | Inflammatory fibroid polyp |

| 16 | 26 | M | Enteric (jejunojejunal) | + (small bowel series) | Reduction + enterotomy + polypectomy | Peutz-Jeghers (hamartomatous polyp) |

| 17 | 48 | F | Enteric (ileoileal) | - (Urgent) | Reduction + diverticulectomy | Meckel’s diverticulum |

| 18 | 72 | M | Colonic (colocolic) | + (CT) | Left hemicolectomy | Adeno CA |

| 19 | 56 | F | Enteric (ileoileal) | + (CT) | Reduction + segmental ileal resection | Metastatic Adeno CA |

| 20 | 51 | F | Enteric (ileoileal) | - (Urgent) | Reduction + diverticulectomy | Meckel’s diverticulum |

The pathological cause of intussusception was identified in 18 (90%) cases (Table 2). Benign pathology was seen in 14 cases (77.8%) and malignancy in four (22.2%). Among enteric intussusception, 14 cases were secondary to a benign process, including submucosal lipoma, Peutz Jeghers polyps, inflammatory fibroid polyp, intussuscepting Meckel diverticulum, fibroid polyp (Figure 2B), and congenital band adhesions. One malignant case was secondary to metastatic lung adenocarcinoma. All colonic intussusceptions resulted from a malignant lesion. The causes of colonic intussusception were secondary to primary adenocarcinoma in two cases and primary colonic lymphoma in one. No colorectal or rectorectal intussusception was identified in this study.

All patients underwent operative treatment (Table 2). No hydrostatic reduction was attempted in any case. The choice of procedure was determined by the location, size, and cause of the intussusception and the viability of the bowel. All 20 patients underwent laparotomy. En bloc resection (without reduction) was performed in five patients (25%), four of whom underwent right or left hemicolectomy, and one, subtotal colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis because of suspicion of malignancy. Reduction of the intussuscepted bowel was performed on the remaining 15 patients (75%). Among these, segmental resection was performed in nine, two of whom underwent diverticulectomy, two, enterotomy and polypectomy, and one, congenital band exision.

Postoperative complications occurred in four of 20 patients (20%): superficial wound infection in two (10%), pneumonia in one (5%), and severe sepsis in one (5%). There were no anastomotic leaks or intra-abdominal abscesses. There was one perioperative death (5%), which was secondary to severe sepsis complicated by multiple organ failure 6 d after the operation.

Adult intussusception is an uncommon clinical entity encountered by surgeons. The exact mechanism is unknown, and it is believed that any lesion in the bowel wall or irritant within the lumen that alters normal peristaltic activity is able to initiate invagination[26]. Ingested food and the subsequent peristaltic activity of the bowel produce an area of constriction above the stimulus and relaxation below, thus telescoping the lead point (intussusceptum) through the distal bowel lumen (intussuscipiens)[12]. The most common locations are at the junctions between freely moving segments and retroperitoneally or adhesionally fixed segments[67].

About 90% of occurrences in adults have a lead point, a well-definable pathological abnormality. In general, the majority of lead points in the small intestine consist of benign lesions, such as benign neoplasms, inflammatory lesions, Meckel’s diverticuli, appendix, adhesions, and intestinal tubes. Malignant lesions (either primary or metastatic) account for up to 30% of cases of intussusception in the small intestine[25]. On the other hand, intussusception occurring in the large bowel is more likely to have a malignant etiology and represents up to 66% of the cases[2568]. In our study malignant etiology was detected in all cases of colonic intussusception.

The clinical presentation in adult intussusception is often chronic, and most patients present with non-specific symptoms that are suggestive of intestinal obstruction. Abdominal pain is the most common symptom followed by vomiting and nausea[12]. Abdominal masses are palpable in 24%-42% of patients, and identification of a shifting mass or one that is palpable only when symptoms are present is suggestive of intussusception or volvulus[125]. In our series, an abdominal mass was only palpable in one patient (5%).

The symptoms in cases of adult intussusception are so non-specific that a clinical diagnosis beyond bowel obstruction is rarely made before surgery.

Several imaging techniques may help to precisely identify the causative lesion preoperatively. Plain abdominal X-rays are typically the first diagnostic tool and show signs of intestinal obstruction, and may provide information regarding the site of obstruction[89]. Contrast studies can help to identify the site and cause of the intussusception, particularly in more chronic cases. Upper gastrointestinal series may show a “stacked coins” or “coiled spring” appearance[8]. Barium enema examination may be useful in patients with colonic or ileocolic intussusception in which a “cup-shaped” filling defect is a characteristic finding[8]. Barium studies are obviously contraindicated if there is the possibility of bowel perforation or ischemia.

Colonoscopy is also a useful tool for evaluating intussusception, especially when the presenting symptoms indicate a large bowel obstruction[21011]. It may not be advisable to perform endoscopic biopsy or polypectomy in those individuals with long-term symptoms because of the high risk of perforation, which is more likely to happen in the phase of chronic tissue ischemia, and perhaps necrosis because of vascular compromise in intussusception[12].

In our series, three patients underwent colonoscopy, and intussusception was confirmed in two (66.6%). A small-bowel series were performed in three patients. Two (66.6%) patients in diagnostic studies had findings suspicious of intussusception because of obstruction with polyps or tumors.

Ultrasonography has been used to evaluate suspected intussusception. The classic features include the “target and doughnut sign” on transverse view and the “pseudokidney sign” in longitudinal view. The major disadvantage of ultrasound is masking by gas-filled loops of bowel, and operator dependency[10111314].

In recent years, CT has become the first imaging method performed, after plain abdominal X-rays, in the evaluation of patients with non-specific abdominal complaints. The characteristics of intussusception on CT are an early “target mass” with enveloped, excentrically located areas of low density. Later, a layering effect occurs as a result of longitudinal compression and venous congestion in the intussusceptum[15]. Abdominal CT has been reported to be the most useful tool for diagnosis of intestinal intussusception and is superior to other contrast studies, ultrasonography, or endoscopy[15–18]. The reported diagnostic accuracy of CT scans was 58%-100%, especially in recent series[1461619]. The diagnosis of intussusception was based on CT findings in the majority of our cases (10/12); two were based on colonoscopy and two on a small-bowel series. The accuracy was 83.3% for CT, 66.6% for colonoscopy, and 66.6% for small-bowel series. The preoperative diagnostic accuracy was 70% in our series.

Although few reports have described magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of adult intussusception, the general imaging characteristics of intussusception on MRI are similar to those on CT[1820], but fast MR examination, unlike CT, is not technically limited by the presence of previously administered barium for small bowel series[21].

The optimal management of adult intussusception remains controversial. Most of the debate focuses on the issue of primary en bloc resection versus initial reduction, followed by a more limited resection[121922]. Proponents of primary resection cite the high incidence of underlying malignancy, especially in colonic lesions, which mandates en bloc resection. Furthermore, the inability to differentiate malignant from benign etiology preoperatively or intraoperatively also dictates that small bowel intussusception be resected without reduction. The reduction of an intussusception secondary to a malignant lead point is potentially detrimental, as there is the theoretic risk of intraluminal seeding and venous embolization in regions of ulcerated mucosa. Other drawbacks include the increased risk of anastomotic complications (the bowel wall may be weakened during manipulation) and the potential for bowel perforation[1562324].

On the other hand, some authors have recommended a selective approach to resection, taking into consideration the site of intussusception, which influences the type of pathology[225]. They advocate resection of all colonic lesions but a more selective approach for small bowel pathology, as the lower malignancy rate for small bowel intussusception makes the argument for initial resection less convincing.

Recently, minimally invasive techniques have been applied to the treatment of small or large bowel obstructions, specifically to the diagnosis and treatment of adult intussusception. There are several case reports about laparoscopic small bowel resection because of intussusception[2627]. The choice of using a laparoscopic or open approach depends on the clinical condition of the patient, the location and extent of intussusception, the possibility of underlying disease, and the availability of surgeons with sufficient laparoscopic expertise[2829]. In the present study, we did not use laparoscopy for diagnosis or treatment.

In conclusion, intussusception in adults is a rare entity and diagnosis may be challenging because of non-specific symptoms. Surgeons should be familiar with the various treatment options, because the real cause of the intussusception often is accurately diagnosed by laparotomy. CT is the most useful imaging modality in the diagnosis of intussusception. Treatment usually requires resection of the involved bowel segment. Reduction can be attempted in small-bowel intussusception if the segment involved is viable or malignancy is not suspected; however, a more careful approach is recommended in colonic intussusception because of a significantly higher chance of malignancy.

Intestinal intussusception in adults is a rare entity and there is an ongoing controversy regarding the optimal management of this problem. Most surgeons accept that adult intussusception requires surgical resection because the majority of patients have intraluminal lesions. However, the extent of resection and whether the intussusception should be reduced remains controversial.

Authors aimed to evaluate their experience with 20 adult intussusception cases and to clarify the cause, clinical features, diagnosis, and management of this uncommon entity.

The present study was retrospective; however, it highlights the clinical features in adult intussusception and may guide surgeons who encounter this problem.

Intussusception occurs when a segment of bowel and its mesentery (intussusceptum) invaginates the downstream lumen of the same loop of bowel (intussuscipiens). Sliding within the bowel is propelled by intestinal peristalsis and may lead to intestinal obstruction and ischemia.

This is an interesting retrospective study with excellent figures. Although the authors do not show any case with laparoscopic approach, the general statement should be more positive and oriented towards the practice in 2009.

| 2. | Begos DG, Sandor A, Modlin IM. The diagnosis and management of adult intussusception. Am J Surg. 1997;173:88-94. |

| 3. | Weilbaecher D, Bolin JA, Hearn D, Ogden W 2nd. Intussusception in adults. Review of 160 cases. Am J Surg. 1971;121:531-535. |

| 4. | Felix EL, Cohen MH, Bernstein AD, Schwartz JH. Adult intussusception; case report of recurrent intussusception and review of the literature. Am J Surg. 1976;131:758-761. |

| 5. | Tan KY, Tan SM, Tan AG, Chen CY, Chng HC, Hoe MN. Adult intussusception: experience in Singapore. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:1044-1047. |

| 6. | Wang LT, Wu CC, Yu JC, Hsiao CW, Hsu CC, Jao SW. Clinical entity and treatment strategies for adult intussusceptions: 20 years' experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1941-1949. |

| 7. | Sachs M, Encke A. [Entero-enteral invagination of the small intestine in adults. A rare cause of "uncertain abdomen"]. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1993;378:288-291. |

| 8. | Eisen LK, Cunningham JD, Aufses AH Jr. Intussusception in adults: institutional review. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188:390-395. |

| 9. | Cerro P, Magrini L, Porcari P, De Angelis O. Sonographic diagnosis of intussusceptions in adults. Abdom Imaging. 2000;25:45-47. |

| 10. | Hurwitz LM, Gertler SL. Colonoscopic diagnosis of ileocolic intussusception. Gastrointest Endosc. 1986;32:217-218. |

| 11. | Thomas AW, Mitre R, Brodmerkel GJ Jr. Sigmoidorectal intussusception from a sigmoid lipoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;21:257. |

| 12. | Chang FY, Cheng JT, Lai KH. Colonoscopic diagnosis of ileocolic intussusception in an adult. A case report. S Afr Med J. 1990;77:313-314. |

| 13. | Kitamura K, Kitagawa S, Mori M, Haraguchi Y. Endoscopic correction of intussusception and removal of a colonic lipoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:509-511. |

| 14. | Fujii Y, Taniguchi N, Itoh K. Intussusception induced by villous tumor of the colon: sonographic findings. J Clin Ultrasound. 2002;30:48-51. |

| 15. | Bar-Ziv J, Solomon A. Computed tomography in adult intussusception. Gastrointest Radiol. 1991;16:264-266. |

| 16. | Takeuchi K, Tsuzuki Y, Ando T, Sekihara M, Hara T, Kori T, Kuwano H. The diagnosis and treatment of adult intussusception. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:18-21. |

| 17. | Gayer G, Apter S, Hofmann C, Nass S, Amitai M, Zissin R, Hertz M. Intussusception in adults: CT diagnosis. Clin Radiol. 1998;53:53-57. |

| 18. | Warshauer DM, Lee JK. Adult intussusception detected at CT or MR imaging: clinical-imaging correlation. Radiology. 1999;212:853-860. |

| 19. | Barussaud M, Regenet N, Briennon X, de Kerviler B, Pessaux P, Kohneh-Sharhi N, Lehur PA, Hamy A, Leborgne J, le Neel JC. Clinical spectrum and surgical approach of adult intussusceptions: a multicentric study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:834-839. |

| 20. | Marcos HB, Semelka RC, Worawattanakul S. Adult intussusception: demonstration by current MR techniques. Magn Reson Imaging. 1997;15:1095-1098. |

| 21. | Tamburrini S, Stilo A, Bertucci B, Barresi D. Adult colocolic intussusception: demonstration by conventional MR techniques. Abdom Imaging. 2004;29:42-44. |

| 22. | Yalamarthi S, Smith RC. Adult intussusception: case reports and review of literature. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:174-177. |

| 23. | Chang CC, Chen YY, Chen YF, Lin CN, Yen HH, Lou HY. Adult intussusception in Asians: clinical presentations, diagnosis, and treatment. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1767-1771. |

| 24. | Yamada H, Morita T, Fujita M, Miyasaka Y, Senmaru N, Oshikiri T. Adult intussusception due to enteric neoplasms. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:764-766. |

| 25. | Reijnen HA, Joosten HJ, de Boer HH. Diagnosis and treatment of adult intussusception. Am J Surg. 1989;158:25-28. |

| 26. | Karahasanoglu T, Memisoglu K, Korman U, Tunckale A, Curgunlu A, Karter Y. Adult intussusception due to inverted Meckel's diverticulum: laparoscopic approach. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2003;13:39-41. |

| 27. | Zanoni EC, Averbach M, Borges JL, Corrêa PA, Cutait R. Laparoscopic treatment of intestinal intussusception in the Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: case report and review of the literature. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2003;13:280-282. |

| 28. | Alonso V, Targarona EM, Bendahan GE, Kobus C, Moya I, Cherichetti C, Balagué C, Vela S, Garriga J, Trias M. Laparoscopic treatment for intussusception of the small intestine in the adult. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2003;13:394-396. |

| 29. | Jelenc F, Brencic E. Laparoscopically assisted resection of an ascending colon lipoma causing intermittent intussusception. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2005;15:173-175. |