INTRODUCTION

We report the first known case of both Noonan syndrome and Whipple’s disease (WD) occurring in the same patient. Noonan syndrome is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder that causes abnormal development, originally labeled as the “male Turner syndrome.” It affects at least 1 in 2500 male and female children and is thought to be due to a genetic mutation of PTPN11 gene, first discovered in 2001. Signs and symptoms include webbing of the neck, changes in the sternum (pectus excavatum), facial abnormailities (low-set or abnormally shaped ears, ptosis, hypertelorism, epicanthal folds, antimongoloid palpebral slant, micrognathia), cubitus vulgaris, congenital heart disease (especially pulmonary stenosis, and/or atrial septal defect), and variable hearing loss. Mild mental retardation is present in approximately 25% of cases. WD is a rare systemic infection caused by a non-acid fast gram positive bacillus, Tropheryma whipplei (T. whipplei). Thus far fewer than 1000 reported cases have been described with an annual incidence of approximately 30 cases per year since 1980. In 1907, Whipple first reported this syndrome in an original case report. Invasion or uptake of the bacillus is widespread throughout the body, including the intestinal epithelium, macrophages, capillary and lymphatic endothelium, colon, liver, brain, heart, lung, synovium, kidney, bone marrow, and skin. Advancement in diagnosis has only recently occurred with the first successful culture of T. whipplei in the year 2000; nearly a full century after the disease entity was first described.

CASE REPORT

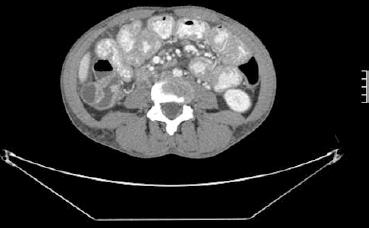

A 36-year-old female with history of Noonan syndrome developed fatigue, anorexia, arthritis of the knees and hands with a diffuse rash, night sweats, and an unintentional fifteen pound weight loss over the past 4 mo. One year prior, she had an endoscopic workup performed for iron deficiency, which was significant for erosive esophagitis. Of note, ileal and duodenal biopsies were histologically normal. Prior to this consultation, she had recently seen a rheumatologist and was placed on prednisone and Plaquenil for arthritis thought to be of rheumatoid origin. She then developed an episode of acute right lower quadrant abdominal pain and an abdominal computerized tomography (CT) scan was ordered. This revealed lymphadenopathy and diffuse thickening of the small bowel (Figure 1). The patient was then referred for gastroenterological consultation at which time her chief complaints were fatigue, arthralgias, and anorexia. She denied abdominal pain, diarrhea, hematochezia, fevers, chills, nausea, or vomiting.

Figure 1 Computerized tomography scan image displaying diffuse lymphadenopathy and small bowel wall thickening.

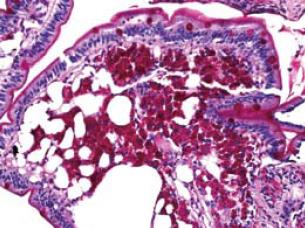

She was 5'2" feet tall and weighed 117 pounds. Physical examination was significant for arthritis of the knees and hands with mild diffuse hyperpigmented skin. Laboratory tests were significant for sedimentation rate of 33, hemoglobin 9.6, and a white blood cell count of 10.4 without a shift. At this time, concern for lymphoma warranted further investigation. Thus, enteroscopy was performed in May 2006. The only significant endoscopic findings were a mild edematous yellowish mucosa without friability in the distal duodenum and jejunum. Random small bowel biopsies revealed intestinal mucosa in which the lamina propria was markedly expanded due to an infiltrate of histiocytic-appearing cells with foamy cytoplasm and a periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain showing extensive PAS positive material within the foamy macrophages; AFB stain was negative (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of WD. Due to the patient’s inability to psychologically tolerate intravenous therapy and an allergy to penicillin, she was placed on an oral regimen of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double-strength twice daily for a 12 mo course.

Figure 2 A periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain showing extensive PAS positive material within the foamy macrophages (small intestinal biopsy).

At follow up in December 2006, she had a remarkable clinical improvement and returned to her baseline clinical status. That is, she had a marked improvement in weight and complete resolution of anemia, arthritis, rash, and bowel wall thickening and lymphadenopathy on CT scan.

DISCUSSION

We report the first known case of both Noonan syndrome and WD occurring in the same patient. Noonan syndrome is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder that causes abnormal development, originally labeled as the “male Turner syndrome.” It affects at least 1 in 2500 male and female children and is thought to be due to a genetic mutation of PTPN11 gene, first discovered in 2001.

WD is a rare systemic infection caused by a non-acid fast gram positive bacillus, T. whipplei. Thus far, fewer than 1000 reported cases have been described[1], with an annual incidence of approximately 30 cases per year since 1980. In postmortem studies, the frequency of the disease is less than 0.1%[2]. In 1907 Whipple first reported this syndrome in an original case report[3]. The ability to diagnose WD was advanced in 1949 with PAS staining which identified granules within macrophages that likely represented degenerating bacterial forms[4]. Invasion or uptake of the bacillus is widespread throughout the body, including the intestinal epithelium, macrophages, capillary and lymphatic endothelium, colon, liver, brain, heart, lung, synovium, kidney, bone marrow, and skin. The chronic, insidious nature of WD may at least be in part due to the long doubling time of 17 d. Advancement in diagnosis has only recently occurred with the first successful culture of T. whipplei in the year 2000; nearly a full century after the disease entity was first described. One year later, in 2001, the first phenotypic characterization of the Whipple bacillus occurred, resulting in the renaming of the bacterium to T. whipplei[5].

Clinical manifestations include four cardinal findings: arthralgias, weight loss, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Neurological involvement (dementia, supranuclear ophthalmoplegia, nystagmus, and myoclonus) has been recognized in up to 40% of patients, either as initial manifestations or during the course of the disease. Less common symptoms include fever and skin hyperpigmentation. There may also be symptoms or signs related to cardiac disease (dyspnea, pericarditis, culture-negative endocarditis), pleuropulmonary disease (pleural effusions) or mucocutaneous disease.

Traditionally, the disease has been described in two stages: a prodromal stage and a much later steady-state stage. The time between these stages varies; however, it typically averages 6 years[6]. The prodromal stage is predominantly characterized by nonspecific symptoms including arthralgias and fatigue. More specific findings such as weight loss, diarrhea, and multi organ involvement occur in the steady state stage. Approximately 15% of patients with WD do not present with classic signs and symptoms of the disease; therefore, the diagnosis should be considered in a broad range of clinical scenarios[78]. Furthermore, immunosuppressed patients can display a more rapid progression of the disease[910].

The clinical manifestations of the disease are believed to be caused by infiltration of T. whipplei into various tissues. The patient’s immune system reacts by incorporating the bacteria into tissue macrophages. Serum studies typically have presented nonspecific findings, therefore biopsy of the appropriate tissue is essential for diagnosis. Tissue samples from the small bowel show expanded villi containing PAS staining macrophages. After the discovery of PAS staining in 1949, the detection of bacteria in macrophages in 1961 further contributed to our understanding of WD[41112]. However, the only specific diagnostic tests for WD include determining the presence of T. whipplei DNA through molecular amplification of the 16S rRNA of T. whipplei by polymerase-chain-reaction (PCR) and cell culture of the organism[13–15]. Subsequently, this finding led to electron microscopy, which in turn led to DNA testing for T. whipplei. Most recently, in 2003 the full sequencing of two genomes from two different strains of T. whipplei has been reported[61617].

In conjunction with clinical signs and symptoms, endoscopy is an important diagnostic modality in WD. Endoscopic examination of the postbulbar region of the duodenum and jejunum includes findings consisting of pale yellow and shaggy mucosa alternating with eroded, erythematous, or mildly friable mucosa[18]. Several biopsy samples should be studied because the lesions can be sparse and focal[6].

In the era before routine access to antibiotics, WD was a universally fatal disease. The discovery of antibiotics has resulted in antibiotics as the mainstay of therapy for WD. Treatment regimens are tailored for severity of disease, however, lack of well-controlled trials limits recommendations to reports of experience. The first reported efficacy of antibiotic treatment with chloramphenicol occurred in 1952[19]. With the progressive discovery of safer antibiotics, tetracycline at one time was the mainstay of therapy for many years. However, a comprehensive review by Keinath et al[20] subsequently revealed an overall relapse rate of 35% with a high CNS relapse rate among patients treated primarily with tetracycline[2122]. As a result, the current standard of therapy includes an initial phase of intravenous antibiotics known to penetrate the blood brain barrier followed by 12 mo of oral maintenance treatment. A typical course often includes ceftriaxone or penicillin for two weeks followed by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength twice per day for one year. Depending on allergies to medications, antibiotics can be substituted as needed.