Published online Mar 21, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1388

Revised: February 13, 2009

Accepted: February 20, 2009

Published online: March 21, 2009

We report a case of isolated gastrointestinal metastasis from breast lobular carcinoma, which mimicked primary anal cancer. In July 2000, an 88-year-old woman presented with infiltrating lobular cancer (pT1/G2/N2). The patient received postoperative radiotherapy and hormonal therapy. Four years later, she presented with an anal polypoid lesion. The mass was removed for biopsy. Immunohistochemical staining suggested a breast origin. Radiotherapy was chosen for this patient, which resulted in complete regression of the lesion. The patient died 3 years after the first manifestation of gastrointestinal metastasis. According to the current literature, we consider the immunohistochemistry features that are essential to support the suspicion of gastrointestinal breast metastasis, and since we consider the gastrointestinal involvement as a sign of systemic disease, the therapy should be less aggressive and systemic.

- Citation: Puglisi M, Varaldo E, Assalino M, Ansaldo G, Torre G, Borgonovo G. Anal metastasis from recurrent breast lobular carcinoma: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(11): 1388-1390

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i11/1388.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.1388

Over the last 10 years, the early diagnosis and development of new therapies have increased the survival time and disease-free survival of women with breast cancer, but long-term survivors are also at risk of developing distant metastases. Breast cancer is usually associated with lymphatic spread and blood metastases to the lung, bones and liver. In this paper, we report a case of isolated gastrointestinal metastasis from breast carcinoma, which mimicked primary anal cancer.

On July 2000, an 88-year-old woman presented with a right latero-cervical mass that was hard and increasing in volume, which extended up to the supraclavear region. Physical examination showed a right breast tumor (1 cm in diameter) of the superior external quadrant, with some palpable homolateral axillary nodes. Abdominal ultrasonography and bone scanning did not reveal metastases, but thoracic computed tomography (CT) showed mediastinal lymph nodes < 1 cm in size. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and cancer antigen 15.3 (CA15.3) level was normal. The patient underwent right external superior quadrantectomy with right axillary and latero-cervical lymphadenectomy. The histological examination showed an infiltrating lobular carcinoma (ILC) with metastases in all 10 nodes removed (pT1/G2/N2). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for estrogen receptor (ER) protein (90%) and c-erbB2. The tumour cells showed a low mitotic index (15%).

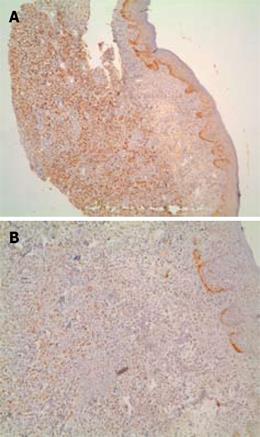

The patient received postoperative radiotherapy and hormonal therapy (tamoxifen). Four years later, some new right axillary lymph node metastases were discovered at physical examination and therefore removed. The histological examination confirmed the diagnosis of lymphatic metastasis from ILC. Two months after lymphadenectomy, the patient presented with tenesmus and a painful anal polypoid lesion (Figure 1). The mass was removed for biopsy. The immunohistochemical staining was similar to primary breast tumor [95% ER and 10% progesterone receptor (PR)], which suggested a breast origin (Figure 2). Mib1 was 25% positive, while c-erbB2 was negative. No other site of disease was found by abdominal CT and bone scintigraphy. Radiotherapy was chosen for this patient, which led to complete regression of the lesion, but later an anal stenosis appeared without any changes in defecation. Treatment with anastrozole was then started. At follow-up, there was no evidence of progressive disease for 2 years, after which the level of CA15.3 began to increase, and some new right axillary lymph nodes metastases appeared. The patient underwent axillary lymphadenectomy and adjuvant hormonal therapy was continued.

Six years later, during follow-up, abdominal CT showed a suspicious increase in antral wall thickness, but endoscopic examination revealed only a peptic stenosis that was treated by pneumatic dilatation. Twelve months later, the patient underwent local radiotherapy for a relapse of anal lesions. Two months afterwards, during umbilical hernioplasty a diagnosis of peritoneal carcinosis was made. The patient died 3 years after the first manifestation of anal metastasis and 6 years after the diagnosis of breast cancer.

Gastrointestinal metastases of breast cancer are rare and usually associated with disseminated disease. The most frequent organ involved is the stomach[12]. Survival after diagnosis of gastrointestinal metastases is poor, with few patients surviving beyond 2 years. The average survival from time of recurrence is 12-16 mo[12].

Despite their rare clinical manifestations (only 0.07% of cases)[3], some necroscopy studies have described an incidence rate of colon involvement that varies from 3% to 18%[45]. The risk of a second primary tumor following breast cancer is about 12%[6], and the incidence of metachronous primary colorectal cancer is estimated to be about 1%[78]. In a review of the literature, we found 15 cases of solitary rectal metastasis from breast carcinoma, but only one case of anal localization has been reported[9] and none from lobular breast carcinoma. Breast ILC is responsible for the majority of metastases in the GI tract, with a metastasis rate of 4.5% vs 0.2% from infiltrating ductal carcinoma[10].

Clinical-histological features that lead us to suspect a diagnosis of gastrointestinal breast metastasis versus primary colon cancer are: (1) ER or PR protein and gross cystic disease fluid protein (GCDFP-15) are strongly positive in metastatic breast carcinomas[10–12]; (2) absence of dysplasia in adjacent colonic epithelium suggests a metastatic growth; and (3) history of breast cancer. However, some authors have shown the presence of cells positive for ER or PR in colorectal cancer, but their concentration tends to be lower than in breast cancer[1314]. In our case, GCDFP-15 was not tested for, but the immunohistochemical staining of anal biopsy was strongly positive for ERs (90%). The disease-free interval between primary breast cancer and gastrointestinal involvement varies from synchronous presentation to up to 30 years[1].

If we consider that gastrointestinal involvement is a sign of systemic disease, systemic therapy should be initiated. In the literature, a common attitude towards isolated gastrointestinal lesions is to undertake local surgical treatment associated with hormonal or chemotherapy. Surgery is usually necessary for an exact diagnosis or for acute clinical manifestations. In our case, the diagnosis was made easily as the tumor was external to the anal canal, therefore, a more aggressive approach such as anorectal amputation (Miles’ operation) was excluded.

It is very difficult to suspect anal metastasis from breast cancer by formulating the diagnosis by clinical, endoscopic and radiological features. Only a previous history of breast cancer and immunohistochemical analysis of anal biopsies compared with original breast carcinoma pathology allows a correct diagnosis. On the other hand, accurate identification of the disease is essential since the treatment is different in the case of primary or secondary cancer. In the case of breast secondaries, several schedules of chemo- and hormonal therapy for ER/PR-positive tumors are of great benefit. Radiotherapy is strongly recommended in elderly patients rather than surgery, which should be limited to obtaining a diagnosis, or in cases with complications.

| 1. | Schwarz RE, Klimstra DS, Turnbull AD. Metastatic breast cancer masquerading as gastrointestinal primary. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:111-114. |

| 2. | Taal BG, den Hartog Jager FC, Steinmetz R, Peterse H. The spectrum of gastrointestinal metastases of breast carcinoma: II. The colon and rectum. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:136-141. |

| 3. | Hoff J, Portet R, Becue J, Fourtanier G, Bugat R. [Digestive tract metastases of breast cancers]. Ann Chir. 1983;37:281-284. |

| 4. | Gifaldi AS, Petros JG, Wolfe GR. Metastatic breast carcinoma presenting as persistent diarrhea. J Surg Oncol. 1992;51:211-215. |

| 5. | Cervi G, Vettoretto N, Vinco A, Cervi E, Villanacci V, Grigolato P, Giulini SM. Rectal localization of metastatic lobular breast cancer: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:453-455. |

| 6. | Raymond JS, Hogue CJ. Multiple primary tumours in women following breast cancer, 1973-2000. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1745-1750. |

| 7. | Agarwal N, Ulahannan MJ, Mandile MA, Cayten CG, Pitchumoni CS. Increased risk of colorectal cancer following breast cancer. Ann Surg. 1986;203:307-310. |

| 8. | Levi F, Te VC, Randimbison L, La Vecchia C. Cancer risk in women with previous breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:71-73. |

| 9. | Haberstich R, Tuech JJ, Wilt M, Rodier JF. Anal localization as first manifestation of metastatic ductal breast carcinoma. Tech Coloproctol. 2005;9:237-238. |

| 10. | Borst MJ, Ingold JA. Metastatic patterns of invasive lobular versus invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast. Surgery. 1993;114:637-641; discussion 641-642. |

| 11. | Monteagudo C, Merino MJ, LaPorte N, Neumann RD. Value of gross cystic disease fluid protein-15 in distinguishing metastatic breast carcinomas among poorly differentiated neoplasms involving the ovary. Hum Pathol. 1991;22:368-372. |

| 12. | O'Connell FP, Wang HH, Odze RD. Utility of immunohistochemistry in distinguishing primary adenocarcinomas from metastatic breast carcinomas in the gastrointestinal tract. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:338-347. |

| 13. | Bracali G, Caracino AM, Rossodivita F, Bianchi C, Loli MG, Bracali M. Estrogen and progesterone receptors in human colorectal tumour cells (study of 70 cases). Int J Biol Markers. 1988;3:41-48. |

| 14. | Kaufmann O, Deidesheimer T, Muehlenberg M, Deicke P, Dietel M. Immunohistochemical differentiation of metastatic breast carcinomas from metastatic adenocarcinomas of other common primary sites. Histopathology. 1996;29:233-240. |