INTRODUCTION

Although hydatid cysts can occur in any location, echinococcosis is usually found in the liver and lung. Extrahepatic hydatidosis has been described in the peritoneal cavity, retroperitoneum, spleen, kidney, adrenal glands and even in the spine, myocardium and abdominal wall[12]. Most abdominal extrahepatic hydatidosis patients usually present with a clinical picture of abdominal pain or discomfort, or with more specific symptoms, such as an anaphylactic reaction or fever. Diagnostic difficulties are evident in these cases, especially when the disease evolution is unknown and neither clinical nor analytical examinations indicate a hepatobiliary source of the symptoms[3]. Complications resulting from this disease are uncommon. Patients with intestinal obstruction have been described as being exceptional cases of extrahepatic hydatidosis. Surgery is considered the treatment of choice by most authors[4].

We present here a case of fistulization of an adrenal hydatid cyst into an intestinal loop and review the presentation, diagnosis and surgical treatment of extrahepatic echinococcosis in such a location.

CASE REPORT

A 70-year old patient with a history of heart failure and chronic atrial fibrillation visited our hospital for treatment. She underwent surgery for left renal hydatid cysts 30 years ago. Physical examination revealed that she had an incised hernia and history of surgery for gastric ulcer, appendectomy and left hip fracture.

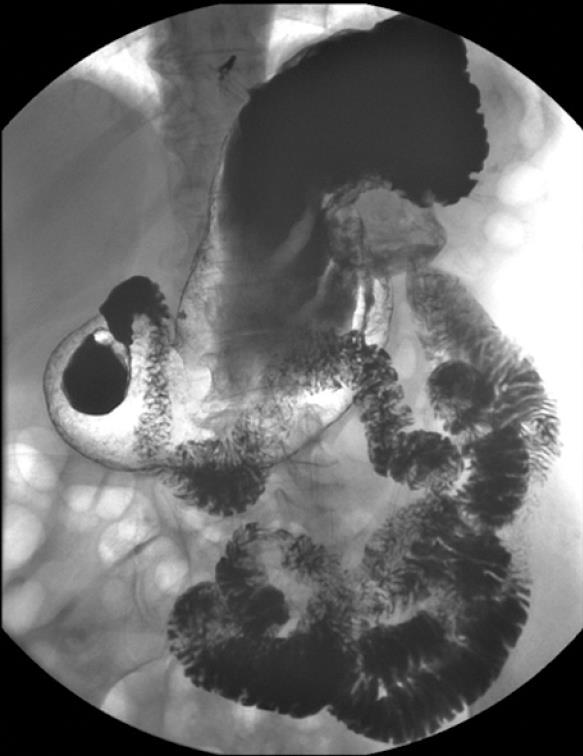

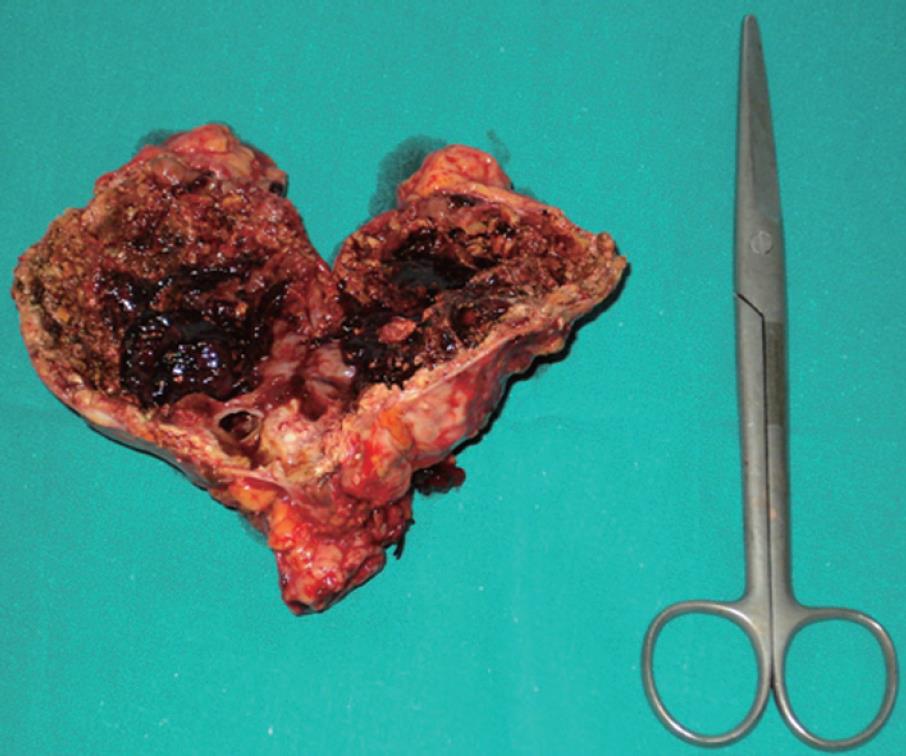

The patient arrived at the Emergency Department with a 4-d history of dull abdominal pain, more intense in the left hypochondrium, and a temperature of 38°C. On examination, a mass and pain in the left epigastrium-hypochondrium were observed on palpation. Blood tests revealed leukocytosis (15 000) with discrete neutrophilia and eosinophils within normal values as well as anemia within the transfusion range (Hb: 7.3; HT: 22). The urinalysis was normal. A simple abdominal X-ray showed a calcified mass in the left epigastric region without signs of intestinal perforation or obstruction. While she was on observation in the hospital, the patient was hemodynamically stable at all times after the transfusion of two units of packed red blood cells. Given the medical history and clinical picture of the patient, an abdominal CT scan was performed, revealing a 9-cm mass with peripheral calcification, wall thickening and central partial fluid image, which seemed to be related to the left kidney’s upper pole, in contact with the stomach which was impressed on its posterior wall. An inflamed-looking loop was observed in the left hypochondrium, with calcification inside and adjacent fluid, which showed no cleavage plane and was highly suspected of being a fistula. Serum IgE (ELISA) was tested for echinococcus and later read as being within the normal range. The patient’s evolution during hospitalization was satisfactory. Her fever subsided after antibiotic treatment and strict diet. Subsequent blood tests were normal and no further transfusion was required. In an outpatient setting, a gastroduodenal transit study was performed, showing a calcified hydatid cyst in a retrogastric location communicating with a proximal jejunal loop. No intraluminal repletion defects were observed in the remaining loops (Figure 1). Following diagnosis of a left adrenal primary cyst with a possible hydatid origin, complicated by a fistula of jejunal loop, the patient was surgically intervened via a medium laparotomy with an abdominal approach, which allowed for the confirmation of a 12 cm × 9 cm calcified cyst in the left kidney’s upper pole, with fistulization into a proximal jejunal loop through the inflamed supramesocolic tract. En-block resection of the mass together with the adrenal gland was performed, avoiding opening of the said mass at all times, including closure of the enteric fistula (Figure 2). No perioperative anti-helminth treatment was needed because there was no surgical dissemination, and no peritoneal involvement of the rest abdominal cavity was observed during surgery. The patient was discharged 12 d after surgery, with a favorable outcome. Anatomic pathology confirmed the diagnosis of a calcified hydatid cyst of left adrenal origin.

Figure 1 Gastroduodenal transit study showing a calcified mass in a retrogastric location communicating with a proximal jejunal loop.

Figure 2 Surgical specimen showing en-block resection of the hydatid cyst together with the adrenal gland.

DISCUSSION

Sixty to seventy percent of hydatid cysts involve the liver, 5%-15% involve the lung and only 0.5% involve the adrenal glands, an uncommon location for a primary cyst not related to a generalized hydatidosis[5].

Diagnostic difficulties arise when the evolution of the disease appearing outside the abdominal cavity (myocardium, spine, thyroid gland) is unknown. Abdominal cysts usually have a non-specific clinical presentation and their most common symptom is abdominal pain[6]. However, other symptoms may be experienced, such as pain in the renal fossa, relatively non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms (dyspepsia, nausea, vomiting, constipation) or even a mass palpable on physical examination[7]. Sudden abdominal pain in such patients may be an indicator of intracystic hemorrhage, rupture or infection, and intracystic hemorrhage is the potentially most dangerous complication[89]. The diagnosis of hydatid cyst in our patient was easy due to her history of hydatidosis and a palpable mass felt in the epigastrium on physical examination. Simple X-ray, necessary in any urgent admission due to fever and abdominal pain, revealed a calcified cyst in the said location which, together with the fever and leukocytosis, indicated a super-infection of the same location. As in the case in question, Akcay[10], described 9 patients with adrenal hydatid cysts. All plain abdominal X-rays revealed calcifications between the 12th thoracic and the 1st lumbar vertebrae, which is probably related to the silent growth and long evolution of this type of cyst over time. Abdominal CT scan and ultrasound usually confirm the diagnosis with 93%-98% sensitivity for ultrasound and 97% for CT[11]. It was reported that the presence of calcifications in the adrenal mass greatly supports a diagnosis of hydatid cyst in this location[1112]. In our case, the study with barium contrast was important, since the patient presented with recurrent fever episodes and elimination via the feces of echinococcus hydatids. We found this study very useful both to confirm the enteric fistula and to indicate surgery. Even though this is an uncommon complication, it might be interesting to bear these diagnostic tests in mind, particularly in patients with a history of extrahepatic hydatidosis surgery with suspected disease recurrence and a clinical picture of abdominal cyst complicated by abdominal obstruction and super-infection. New laboratory tests for echinococcus such as HAI, ELISA or IgE assist in diagnosis, but their negative results, described in these cases by some authors[511] do not rule out the presence of disease. It is mandatory to systematically use imaging studies (CT, ultrasound). It must be borne in mind that aside from imaging and laboratory methods, diagnosis is confirmed by macroscopic and microscopic examination of the surgical specimens, which will show the germinal membrane with the daughter hydatids and scolices of cysticercus in intracystic fluid.

Just as in hepatic and pulmonary hydatidosis, surgery is the treatment of choice[13]. Most authors recommend removal of cyst and adrenal gland as the safest and most reliable option[514]. This is normally the case because cysts are usually large, and there is total or partial destruction of the gland on which it lies, and even, as in our case, destruction of surrounding structures and organs. Different incisions have been employed as approaches to the adrenal gland. Most authors do not recommend a laparoscopic approach in case of complex cysts[15]. In order to prevent surgical dissemination, the procedure should be carefully carried out, providing adequate protection of the surgical field and instilling hypertonic saline solution prior to cyst removal. Albendazole (10 mg/kg) or mebendazole (50 mg/kg) should be administered for a month following surgery in case of suspected peritoneal dissemination or when a peritoneal cyst is removed during surgery[1617].

Peer reviewers: Nikolaus Gassler, Professor, Institute of

Pathology, University Hospital RWTH, Aachen, Pauwelsstrasse

30, Aachen 52074, Germany; Paolo Del Poggio, Dr, Hepatology

Unit, Department of Internal Medicine, Treviglio Hospital, Piazza

Ospedale 1, Treviglio Bg 24047, Italy