Published online Mar 7, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1358

Revised: November 25, 2007

Published online: March 7, 2008

AIM: To examine the prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms in a large unselected general population in Japan.

METHODS: In Japan, mature adults are offered regular check-ups for the prevention of gastric cancer. A notice was sent by mail to all inhabitants aged > 40 years. A total of 160 983 Japanese (60 774 male, 100 209 female; mean age 61.9 years) who underwent a stomach check up were enrolled in this study. In addition, from these 160 983 subjects, we randomly selected a total of 82 894 (34 275 male, 48 619 female; mean age 62.4 years) to evaluate the prevalence of abdominal pain. The respective subjects were prospectively asked to complete questionnaires concerning the symptoms of heartburn, dysphagia, and abdominal pain for a 1 mo period.

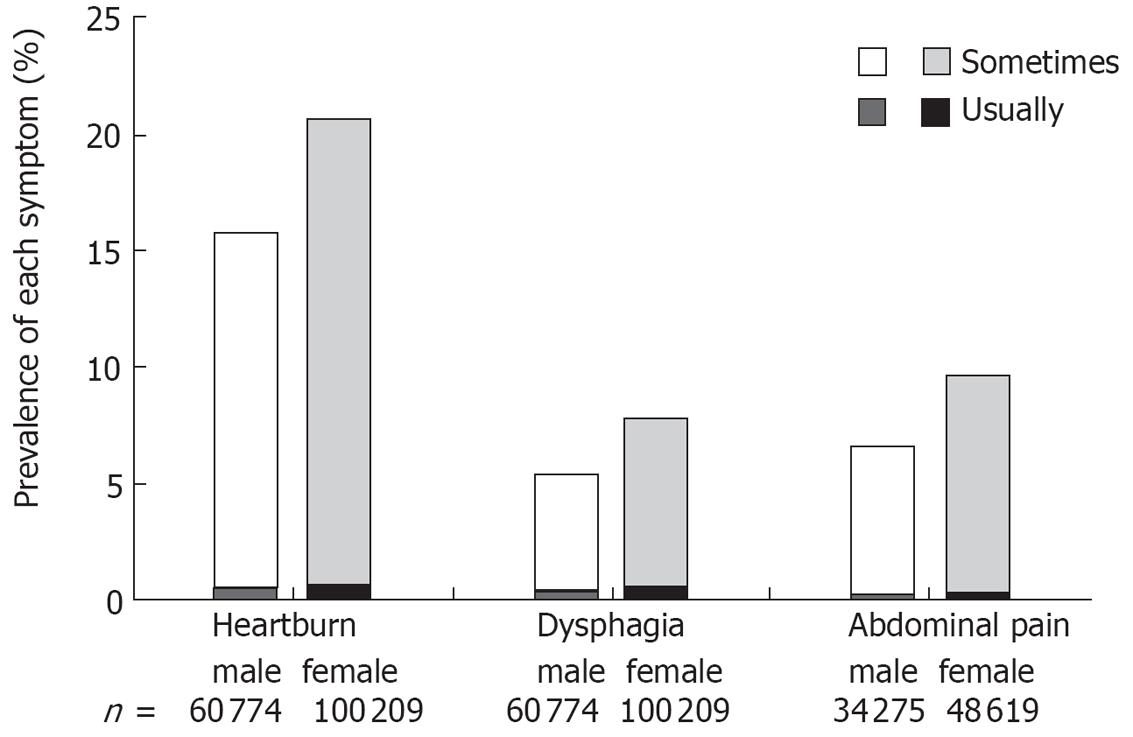

RESULTS: The respective prevalences of the symptoms in males and females were: heartburn, 15.8% vs 20.7%; dysphagia, 5.4% vs 7.8%; and abdominal pain, 6.6% vs 9.6%. Among these symptoms, heartburn was significantly high compared with the other symptoms, and the prevalence of heartburn was significantly more frequent in females than in males in the 60-89-year age group. Dysphagia was also significantly more frequent in female patients.

CONCLUSION: The prevalence of typical GERD symptoms (heartburn) was high, at about 20% of the Japan population, and the frequency was especially high in females in the 60-89 year age group.

- Citation: Yamagishi H, Koike T, Ohara S, Kobayashi S, Ariizumi K, Abe Y, Iijima K, Imatani A, Inomata Y, Kato K, Shibuya D, Aida S, Shimosegawa T. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in a large unselected general population in Japan. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(9): 1358-1364

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i9/1358.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.1358

Heartburn and acid regurgitation, typical symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), are considered to be reasonably specific for diagnosis[12]. The dominant mechanism of GERD is contact of the esophageal mucosa with acid, and GERD can also produce symptoms or signs of tissue injury within the oropharynx, larynx and respiratory tract. Recent studies have suggested GERD causes a wide spectrum of non-esophageal conditions including asthma, non-obstructive dysphagia, and non-cardiac chest pain[34]. Moreover, it has been reported that acid-suppressive therapy resolves heartburn and epigastric pain in GERD patients[56]. Therefore, epigastric pain may be a clinical symptom of GERD.

GERD is a common condition and its prevalence varies in different parts of the world. Several population-based studies have reported its prevalence is more frequent in Western[7–10] than in Eastern countries[1112]. According to the reports from the Ministry of Health and Welfare in 1994, the incidence of heartburn in Japan was only about 2% of the population who complained of symptoms. A recent study from Japan has reported patients complaining of heartburn account for 24.7%-42.2%[13–17]. All of these previous studies were performed on subjects who visited the hospital as outpatients or for routine physical examination[13–17]. However, we have to consider the possibility that outpatients are symptomatic, rather than a true random sample of the population. Furthermore, subjects undergoing their annual medical check-up make a periodic visit to each of the medical institutions for routine physical examination. These subjects may have caused some bias, and subjects who visited the hospital as outpatients or for routine physical examination may not be similar to the general population. Therefore, we decided to collect data from subjects attending a primary health care institution that was conducting an annual medical check-up, rather than using data from hospital-based subjects.

In Japan, mature adults are offered regular check-ups for the prevention of gastric cancer. A notice was sent by mail to all inhabitants aged > 40 years. Thus, the majority of subjects in this study were selected according to their age, and we considered this study sample might be more similar to the general population than those of previous studies, and in this respect, this study is considered to be the first to highlight the prevalence of GERD symptoms in a large unselected Japanese population. This is believed to be the first study to target > 100 000 unselected subjects in Japan, with the aim of: (1) examining the prevalence of heartburn as a typical symptom of GERD and dysphagia as an atypical symptom of GERD; and (2) identifying an association between GERD symptoms and abdominal pain.

The population of Miyagi prefecture comprises 1 889 683 adults (909 795 male, 979 888 female), and there are 1 236 724 adults aged > 40 years old (579 822 male, 656 902 female). In Japan, mature adults are offered regular check-ups for the prevention of gastric cancer. Especially in Miyagi prefecture, those over the age of 40 years are recommended to undergo regular health check-ups. A notice was sent by mail in either the first or second half of the year to all inhabitants aged > 40 years who lived in the prefecture. A list of medical institutions was also included so that the subjects could choose where to have the general check-up. Even those subjects under 40 years old could take the check-up if they so desired.

The center chosen for this study was the Institute of the Miyagi Cancer Society. A total of 160 983 subjects (60 774 male, 100 209 female, mean age 61.9 ± 11.1 years) who underwent a regular check-ups for the prevention of gastric cancer at the above center between January and December 2003 were enrolled in this study in a prospective fashion. The 160 983 subjects were divided into seven geographical areas, according to the place of residence of the inhabitants, namely Sendai, Tome, Sennan, Kesennnuma, Isinomaki, Osaki, and Kurihara. Among these seven geographical areas and 160 193 subjects, we additionally randomly selected a total of 82 894 subjects (34 275 male, 48 619 female, mean age 62.4 ± 11.0 years) to evaluate the prevalence of abdominal pain. Subjects were assigned to the following age groups: 30-39, 40-49, 50-59, 60-69, 70-79, and 80-89 years.

Table 1 shows the questionnaire used in this study. The respective subjects were prospectively asked to complete the questionnaires concerning the symptoms of heartburn, dysphagia, and abdominal pain within a 1 mo period. The subjects were requested to simply answer “yes” or “no” to the symptoms, and if they answered “yes”, they were further questioned on the frequency of symptoms (“usually” or “sometimes”). In addition, concerning the symptom of dysphagia, subjects were asked where it occurred (throat, chest or stomach). The relationship of abdominal pain with meals, if any, was elicited. This questionnaire was designed as a self-reporting instrument to measure symptoms experienced over the month previous to returning the completed questionnaire.

| Please circle the appropriate responses for each of the following symptoms during a 1-mo period | ||

| (1) Do you suffer from the symptom of dysphagia? | ||

| 1: yes | 2: no | |

| (a: usually; b: sometimes) | ||

| (c: throat; d: chest; e: stomach) | ||

| (2) Do you suffer from the symptom of heartburn? | ||

| 1: yes | 2: no | |

| (a: usually; b: sometimes) | ||

| (3) Do you suffer from the symptom of abdominal pain? | ||

| 1: yes | 2: no | |

| (a: usually; b: sometimes) | ||

| (f: before eating; g: after eating; h: no relation) | ||

In order to check for gastric cancer, X-ray examinations were also performed on all the enrolled subjects. In addition, we evaluated disease classification based on X-ray examination independently by two experienced gastrointestinal doctors. This was graded in the present study as: normal, gastric ulcer scar, duodenal ulcer scar, gastric and duodenal ulcer scar, hiatus hernia, and patients in whom further endoscopic testing was necessary, because they were suspected of having gastric cancer (cancer suspected). Hiatus hernia in this study was defined as a circular extension of the gastric mucosa of 3 cm or more above the diaphragmatic hernia[18].

The 160 983 eligible individuals interviewed were considered as a representative sample of the Japanese population. The results are given with a confidence interval of 95%. The values are expressed as frequency, and categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

The mean age of the sample population was 61.9 ± 11.1 years. About 62% of the interviewed subjects (100 209) were women. A total of 160 848 of the 160 983 eligible subjects (99%) responded to the questionnaire on heartburn and dysphagia. Of the total of 82 894 eligible subjects additionally randomly selected to evaluate the prevalence of abdominal pain, 82 484 (99%) responded to this question.

The disease classification by X-ray examination used in this study and the numbers of subjects are shown in Table 2. Normal classification accounted for 86.4%, and the others in who further endoscopic testing was required because they were suspected of having gastric cancer accounted for 9.7%.

| Disease classification by X-rays | n (%) | Male/female |

| Normal | 139 167 (86.4) | (49 338/89 829) |

| Gastric ulcer scar (GU) | 2222 (1.4 ) | (1648/574) |

| Duodenal ulcer scar (DU) | 2346 (1.5) | (1192/1154) |

| Gastric & Duodenal scar (GDU) | 434 (0.3) | (341/93) |

| Hiatus hernia (HH) | 1198 (0.7) | (404/794) |

| Cancer suspected | 15 616 (9.7) | (8080/7536) |

| Total | 160 983 (100.0) | (60 774/100 209) |

The overall and gender-specific prevalence rates for heartburn, dysphagia and abdominal pain are shown in Figure 1. The prevalence of the symptoms respectively in males and females were: heartburn, 15.8% (sometimes 15.3%, usually 0.5%) vs 20.7% (sometimes 20.1%, usually 0.6%); dysphagia, 5.4% (sometimes 5.0%, usually 0.4%) vs 7.8% (sometimes 7.3%, usually 0.5%); and abdominal pain, 6.6% (sometimes 6.5%, usually 0.1%) vs 9.6% (sometimes 9.4%, usually 0.2%). Among these symptoms, heartburn was significantly high compared with the other symptoms, and all symptoms were significantly more common in females than in males.

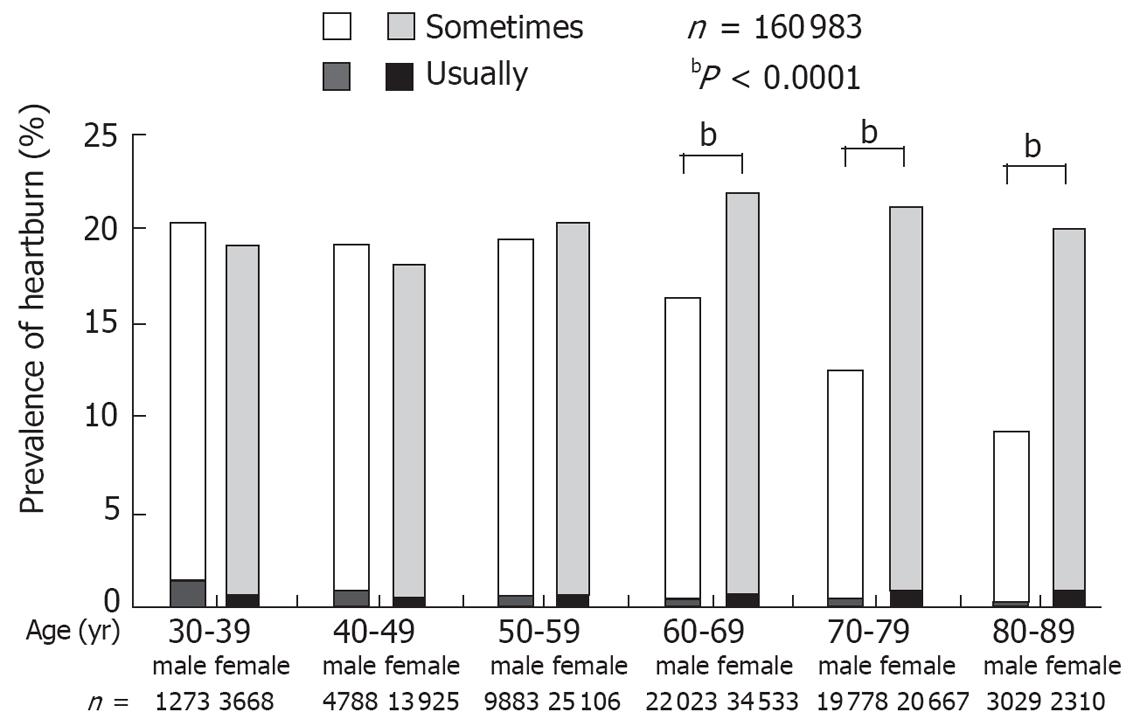

The age- and gender-specific prevalence of heartburn experienced in the month prior to completion of the questionnaires is shown in Figure 2. The prevalence of heartburn remained high with age among women, whereas among men it peaked around the 30-39 years age group, and thereafter declined. The prevalence of heartburn showed a significant age- and gender-related difference in patients in the 60-89 years age group, and the prevalence of heartburn was significantly more frequent in females than in males. The smaller subset of patients reporting “usually” for this symptom is also shown in Figure 2, which was also significantly more frequent in females than in males in the 60-89 years age group.

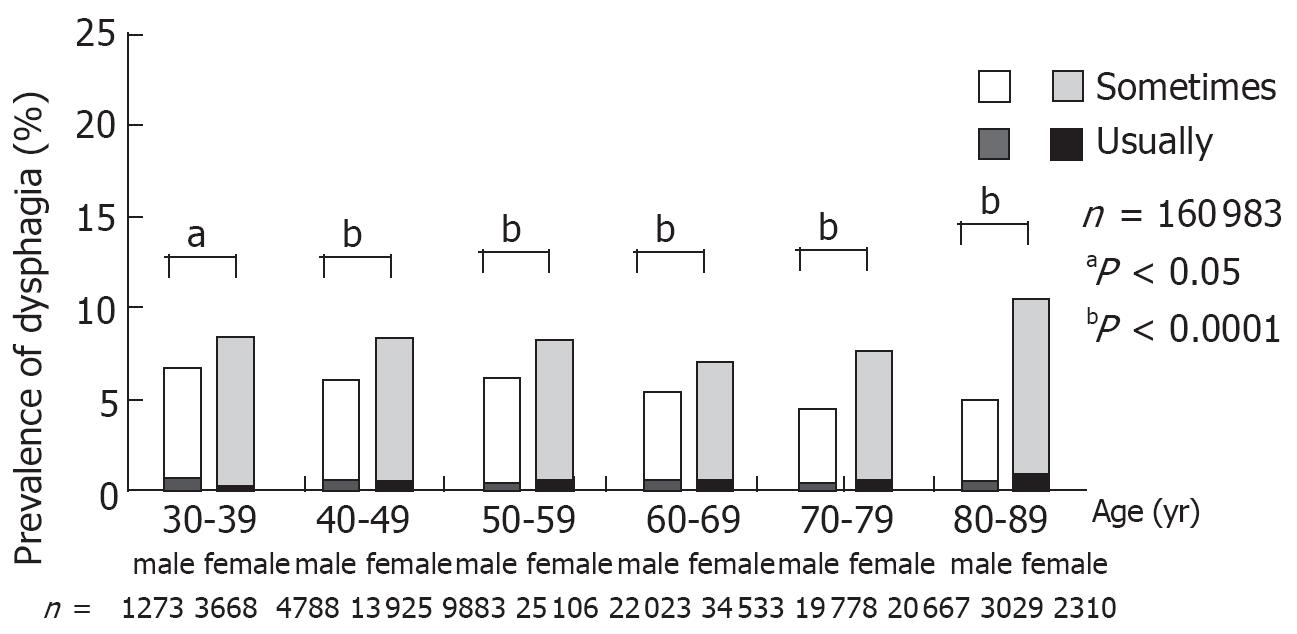

The age- and gender-specific prevalence of dysphagia experienced in the month prior to completion of the questionnaires is shown in Figure 3. Dysphagia was signifi-cantly more frequent in females than in males in all age groups.

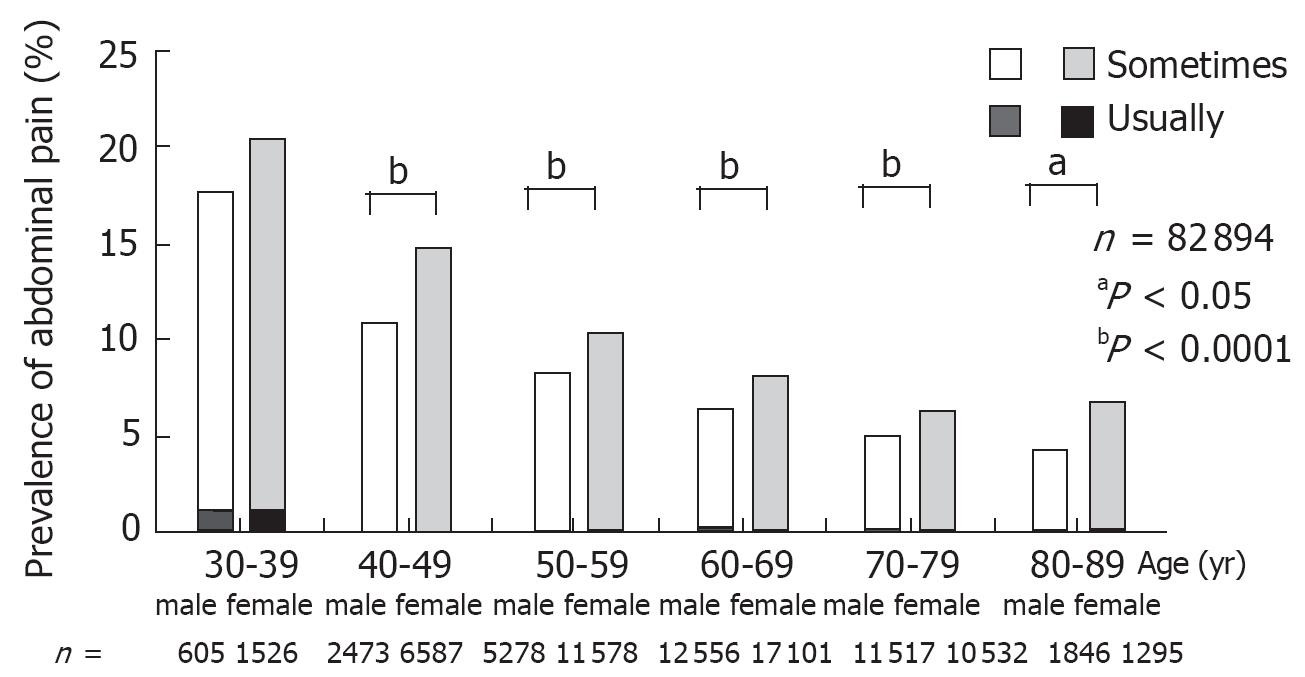

The age- and gender-specific prevalence of abdominal pain experienced in the month prior to completion of the questionnaires is shown in Figure 4. Women were more symptomatic than males in all age groups. Abdominal pain was more prevalent in the younger 30-49 years age group than in the older age groups.

Table 3 shows the prevalence of heartburn among subjects in the dysphagia “usually”, “sometimes” and no dysphagia groups. The subjects with dysphagia had a significantly higher frequency of heartburn than those without it. Table 4 shows the prevalence of dysphagia among subjects with heartburn “usually”, heartburn “sometimes”, and no heartburn. The subjects with heartburn had a significantly higher frequency of dysphagia than those without.

Table 5 shows the prevalence of heartburn and dysphagia among subjects in the abdominal pain “usually”, “sometimes” and no abdominal pain groups. The subjects with abdominal pain had a significantly higher frequency of heartburn and dysphagia than those without.

The prevalence of heartburn and dysphagia was signifi-cantly higher in both males and females with hiatus hernia than those without. The prevalence of abdominal pain was significantly higher in both males and females with gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, and gastric and duodenal ulcer scarring than in those who were scar-free.

This is believed to be the first study that has highlighted the prevalence of GERD symptoms in > 100 000 unselected subjects in a prospective fashion in Japan.

Heartburn has been reported to be specific for the diagnosis of GERD[12]; therefore, we examined heartburn as a typical symptom of GERD. The most important finding was that the monthly prevalence of heartburn was significantly higher (20%) than that for dysphagia and abdominal pain in our Japanese general population.

GERD symptoms are common and its prevalence varies in different parts of the world. The study by El-Serag et al[10] in 2004 used a questionnaire to survey 496 medical center staff for GERD symptoms. They reported that monthly prevalence of heartburn was 34.2%-40.6% in the United States. On the other hand, in Asia the prevalence has varied, but is generally lower than that in Western studies. Wong et al[11] have reported that the prevalence of heartburn among 902 randomly selected people occurring at least monthly was 8.9%, while Cho et al[12] have found a lower prevalence of 4.7% among 2209 randomly selected individuals.

In Japan, Mishima et al[13] have designed a study to clarify the characteristics of GERD, based on 2760 subjects undergoing their annual medical check-up for gastric cancer. They reported that GERD was present in 17.9% of the Japanese people who presented for annual medical health checks. Fujiwara et al[14] have reported the prevalence of heartburn among 6035 routine physical examinations was 24.7%. Watanabe et al[16] have reported the prevalence of GERD among 4139 hospital outpatients was 37.6%. Another study in Japan by Ohara et al[17] has shown a total of 42.2% of Japanese individuals who visited hospital for routine physical examination and outpatients experienced heartburn. All of these previously mentioned studies were performed on subjects who visited a hospital as outpatients or for routine physical examination[13–17]. However, we consider the possibility that outpatients are symptomatic, rather than a true random sample of the population. Furthermore, subjects who undergo their annual medical check-up make a periodic visit to each of the medical institutions for routine physical examinations. These subjects may have caused some bias, and subjects who visited the hospital as outpatients or for routine physical examinations may not be similar to the general population. On the other hand, in this study, the majority of the sample survey was selected according to age. As stated before, those over the age of 40 years are recommended to undergo regular health check-ups, and a notice was sent by mail to all inhabitants who live in Miyagi prefecture, according to their age. We considered this study sample might be more similar to the general population than that in previous studies[13–17], and in this respect, this study is considered to be the first to highlight the prevalence of GERD symptoms in a large unselected Japanese population.

It is difficult to compare previous reports in terms of difference in the prevalence of GERD symptoms in Japan because of the diverse methodologies used. However, several studies have shown the prevalence of GERD symptoms has recently been gradually increasing[15–1719]. The prevalence of heartburn in this study was about 20%, which is considered to be higher than that of previous studies[19].

There are various factors that might be responsible for the recent upward trend in the prevalence of GERD symptoms in Japan. Risk factors for GERD have been shown to include dietary intake[2021], smoking[22], alcohol consumption[23], high body mass index[24], family history of reflux symptom[25], aging population, and the presence of a hiatus hernia[1517]. For the first point, the average fat intake in Japan has increased over the past 20 years[26]. Dietary fat has been shown to increase the frequency of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation[21]. Secondly, the population has become increasingly overweight[27], and obesity may lead to an increase in intragastric pressure[15].Thirdly, it has been reported Japanese patients have a high incidence of H pylori infection and this leads to an atrophic pattern of gastritis with low acid secretion[2829]. The declining prevalence of H pylori infection[30], due to improved hygiene conditions and widespread use of eradication therapy in Japan could also have paradoxically contributed to the increased frequency of GERD. These may be reasons why the prevalence of GERD has recently increased in Japan.

GERD is also associated with a range of other atypical symptom originating in the esophagus, chest and respiratory tract. Several studies have reported approximately one-third of GERD patients suffer from these symptoms, such as dysphagia and chest pain[34]. We also found considerable overlap among heartburn and dysphagia in this survey, and this suggests an association between GERD and dysphagia.

The age and gender relationships with GERD symptoms are still controversial. A study in Japan by Ohara et al[17] has shown GERD symptoms are more common among women, and are unrelated to age. In this study, typical and atypical symptoms were found to be common especially in women. Also, there was a strong relationship between age and gender and the prevalence of symptoms. Our results showed the prevalence of GERD symptoms remained high with age among women, whereas among men, it peaked around the 30-39 years age group, and declined thereafter. One possible reason for high prevalence of GERD in elderly women in Japan may be osteoporosis and kyphosis. Elderly Japanese women tend to have a higher incidence of both osteoporosis and kyphosis than in men the same age[31]. Lumbar kyphosis is the major cause of stooped posture, and this may exacerbate the development of hiatus hernia, which is reported as a risk factor for GERD.

Some studies have reported acid suppressive therapy resolves epigastric pain in patients with GERD[56]. According to these studies, epigastric pain might be one of the clinical symptoms of GERD. In this study, the symptoms of heartburn, dysphagia and abdominal pain also overlapped with each other, similar to previous studies.

The present study has several limitations. First, the main limitation is the fact that the questionnaire was not validated. We estimated the symptom frequency as “usually” or “sometimes”. This may be considered vague terminology for precise evaluation of symptom prevalence. Individual subjects might differently interpret the terms of “usually” or “sometimes”. However, in order to evaluate some digestive symptoms in a large number of subjects, it was necessary to make the questionnaire simple. As a result, we obtained a very high response rate (99%). As a second limitation, the subjects in this study were not a true random sample of the population. Approximately 40% of the population in Miyagi prefecture is aged < 40 years, and the majority of the study sample was aged > 40 years. Thus, the age structure of the study subjects was different from that of the true unselected population in Miyagi prefecture. However, previous Japanese population-based studies were performed on subjects who visited the hospital for routine physical examinations and as outpatients[13–17], and we have to consider the possibility that they are symptomatic, rather than a true random sample of the population. On the other hand, the majority of people in this study were selected according to their age, and they were considered to be less symptomatic than hospital outpatients. Furthermore, we evaluated the clinical symptoms according to each generation. In this regard, this study is considered to be the first to highlight the prevalence of GERD symptoms in a large unselected population of Japanese subjects who are over > 40 years old. This method may have avoided several sources of bias that have tended to occur in previous studies in Japan.

In summary, we clearly described that reflux symptoms are commonly found in the Japanese general population, especially in older women. We conclude that the prevalence of typical GERD symptoms (heartburn) is high, at about 20%, in the Japanese general population, and the frequency is especially high in women in the 60-89 years age group. We found the symptoms of heartburn, dysphagia and abdominal pain overlapped with each other with high frequency.

The prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms is now increasing in Japan.

To examine the prevalence of GERD symptoms in a large unselected general population in Japan.

Although there have been many studies on the prevalence of GERD in Japan, all of these have been performed on subjects who visited the hospital as outpatients or for routine physical examination. However, we have to consider the possibility that outpatients are symptomatic, rather than a true random sample of the population. Furthermore, subjects undergoing their annual medical check-up make a periodic visit to the each of the medical institutions for routine physical examination. These subjects may have caused some bias, and subjects who visited the hospital as outpatients or for routine physical examination may not be similar to the general population. We decided to collect data from subjects attending a primary health care institution for an annual medical check-up rather than using data from hospital-based subjects. The majority of people in this study were selected according to their age (> 40 years), and they were considered to be less symptomatic than hospital outpatients.

This study is considered to be the first to highlight the prevalence of GERD symptoms in a large population of unselected Japanese subjects aged > 40 years old. The prevalence of GERD symptoms among true unselected subjects must continue to be studied in the future.

GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

In this study, the authors ascertained the prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in an extremely large population in Japan. The study was well performed and the conclusions are clear and compatible with those of previous studies.

| 1. | Klauser AG, Schindlbeck NE, Muller-Lissner SA. Symptoms in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Lancet. 1990;335:205-208. |

| 2. | An evidence-based appraisal of reflux disease management--the Genval Workshop Report. Gut. 1999;44 Suppl 2:S1-S16. |

| 3. | Wong WM, Fass R. Extraesophageal and atypical manifestations of GERD. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19 Suppl 3:S33-S43. |

| 4. | Oda K, Iwakiri R, Hara M, Watanabe K, Danjo A, Shimoda R, Kikkawa A, Ootani A, Sakata H, Tsunada S. Dysphagia associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease is improved by proton pump inhibitor. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:1921-1926. |

| 5. | Galmiche JP, Barthelemy P, Hamelin B. Treating the symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a double-blind comparison of omeprazole and cisapride. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:765-773. |

| 6. | Fujiwara Y, Higuchi K, Nebiki H, Chono S, Uno H, Kitada K, Satoh H, Nakagawa K, Kobayashi K, Tominaga K. Famotidine vs. omeprazole: a prospective randomized multicentre trial to determine efficacy in non-erosive gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21 Suppl 2:10-18. |

| 7. | Locke GR 3rd, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd. Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1448-1456. |

| 8. | Ponce J, Vegazo O, Beltrán B, Jiménez J, Zapardiel J, Calle D, Piqué JM; Iberge Study Group. Prevalence of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in Spain and associated factors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 23(1):175-184. |

| 9. | Stanghellini V. Three-month prevalence rates of gastrointestinal symptoms and the influence of demographic factors: results from the Domestic/International Gastroenterology Surveillance Study (DIGEST). Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1999;231:20-28. |

| 10. | El-Serag HB, Petersen NJ, Carter J, Graham DY, Richardson P, Genta RM, Rabeneck L. Gastroesophageal reflux among different racial groups in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1692-1699. |

| 11. | Wong WM, Lai KC, Lam KF, Hui WM, Hu WH, Lam CL, Xia HH, Huang JQ, Chan CK, Lam SK. Prevalence, clinical spectrum and health care utilization of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in a Chinese population: a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:595-604. |

| 12. | Cho YS, Choi MG, Jeong JJ, Chung WC, Lee IS, Kim SW, Han SW, Choi KY, Chung IS. Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Asan-si, Korea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:747-753. |

| 13. | Mishima I, Adachi K, Arima N, Amano K, Takashima T, Moritani M, Furuta K, Kinoshita Y. Prevalence of endoscopically negative and positive gastroesophageal reflux disease in the Japanese. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:1005-1009. |

| 14. | Fujiwara Y, Higuchi K, Watanabe Y, Shiba M, Watanabe T, Tominaga K, Oshitani N, Matsumoto T, Nishikawa H, Arakawa T. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease and gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:26-29. |

| 15. | Fujimoto K, Iwakiri R, Okamoto K, Oda K, Tanaka A, Tsunada S, Sakata H, Kikkawa A, Shimoda R, Matsunaga K. Characteristics of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Japan: increased prevalence in elderly women. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38 Suppl 15:3-6. |

| 16. | Watanabe T, Urita Y, Sugimoto M, Miki K. Gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms are more common in general practice in Japan. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4219-4223. |

| 17. | Ohara S, Kouzu T, Kawano T, Kusano M. Nationwide epidemiological survey regarding heartburn and reflux esophagitis in Japanese. Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2005;102:1010-1024. |

| 18. | Makuuchi H. Clinical study of sliding esophageal hernia--with special reference to the diagnostic criteria and classification of the severity of the disease. Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1982;79:1557-1567. |

| 19. | Hongo M, Shoji T. Epidemiology of reflux disease and CLE in East Asia. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38 Suppl 15:25-30. |

| 20. | El-Serag HB, Satia JA, Rabeneck L. Dietary intake and the risk of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a cross sectional study in volunteers. Gut. 2005;54:11-17. |

| 21. | Nebel OT, Castell DO. Lower esophageal sphincter pressure changes after food ingestion. Gastroenterology. 1972;63:778-783. |

| 22. | Kahrilas PJ, Gupta RR. The effect of cigarette smoking on salivation and esophageal acid clearance. J Lab Clin Med. 1989;114:431-438. |

| 23. | Hogan WJ, Viegas de Andrade SR, Winship DH. Ethanol-induced acute esophageal motor dysfunction. J Appl Physiol. 1972;32:755-760. |

| 24. | El-Serag HB, Graham DY, Satia JA, Rabeneck L. Obesity is an independent risk factor for GERD symptoms and erosive esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1243-1250. |

| 25. | Locke GR 3rd, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd. Risk factors associated with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Med. 1999;106:642-649. |

| 26. | Yoshiike N, Matsumura Y, Yamaguchi M, Seino F, Kawano M, Inoue K, Furuhata T, Otani Y. Trends of average intake of macronutrients in 47 prefectures of Japan from 1975 to 1994--possible factors that may bias the trend data. J Epidemiol. 1998;8:160-167. |

| 27. | Sakamoto M. The situation of the epidemiology and management of obesity in Japan. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2006;76:253-256. |

| 28. | Koike T, Ohara S, Sekine H, Iijima K, Abe Y, Kato K, Toyota T, Shimosegawa T. Helicobacter pylori infection prevents erosive reflux oesophagitis by decreasing gastric acid secretion. Gut. 2001;49:330-334. |

| 29. | Kinoshita Y, Kawanami C, Kishi K, Nakata H, Seino Y, Chiba T. Helicobacter pylori independent chronological change in gastric acid secretion in the Japanese. Gut. 1997;41:452-458. |

| 30. | Fujisawa T, Kumagai T, Akamatsu T, Kiyosawa K, Matsunaga Y. Changes in seroepidemiological pattern of Helicobacter pylori and hepatitis A virus over the last 20 years in Japan. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2094-2099. |

| 31. | Fujiwara S, Mizuno S, Ochi Y, Sasaki H, Kodama K, Russell WJ, Hosoda Y. The incidence of thoracic vertebral fractures in a Japanese population, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 1958-86. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44:1007-1014. |