INTRODUCTION

Midgut volvulus is a condition in which the small bowel or proximal colon twists around the superior mesenteric artery. This condition most commonly presents during the first year of life and has high rates of morbidity and mortality[12]. Midgut volvulus without malrotation is an extremely rare surgical condition, which may also occur during gestation[3–6]. We recently encountered an unusual case in which intrauterine volvulus occurred with prenatal meconium pellets. Emergent prenatal ultrasonography revealed the presence of the ‘coffee bean sign’ in this fetus. The patient required resection of a significant amount of necrotic small bowel and treatment with intra-operative saline irrigation. The patient also needed postoperative gastrografin enema due to persistent meconium ileus. Fortunately, the patient survived and has continued to thrive without parenteral nutrition. We discuss the pathogenesis of intrauterine midgut volvulus associated with complicated meconium ileus and the issues surrounding their emergent diagnosis and management.

CASE REPORT

A 27-year-old pregnant woman was referred to our clinic at 33 wk of gestation because of fetal intestinal dilatation found on sonography, and the onset of preterm labor. Routine examinations at a local clinic had revealed a dilated intestine in the fetus, but this had improved spontaneously four weeks earlier. Transabdominal ultrasound on referral showed a segment of markedly dilated fetal intestine, which suggested a closed loop obstruction (Figure 1). Fetal ultrasound measurements were appropriate for the gestational age, and the Doppler indices were normal. No ascites was seen in the fetal abdomen. As it was possible the bowel obstruction would be complicated by intestinal necrosis, preterm delivery was considered beneficial. At 33 wk and two days, a male infant was delivered transvaginally. The patient weighed 2690 g and had Apgar scores of 8 and 9 at 1 and 5 min, respectively.

Figure 1 A fetal sonogram showing dilated bowel loops with the appearance of a ‘coffee bean sign’.

No ascites was seen in the fetal abdomen.

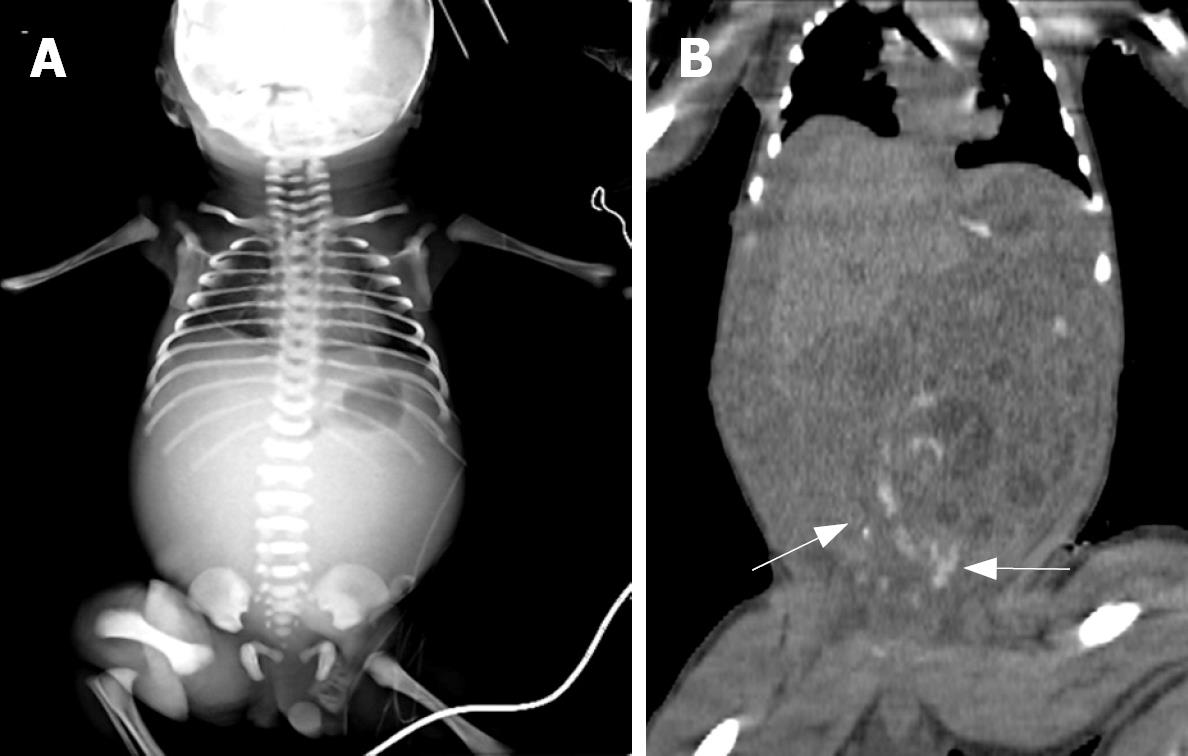

The abdomen was distended markedly and there was a bluish skin discoloration on the periumbilical abdominal skin. Nasogastric aspiration recovered 10 mL of bilious material. A rectal examination was normal. Initial laboratory values included a white blood cell count of 26 000/mm3, a platelet count of 416 000/mm3 and prothrombin time of 11 s. Blood gas values from the umbilical artery were pH 7.14, PO2 51.3 mmHg and PCO2 60.44 mmHg. A plain supine abdominal radiograph did not demonstrate bowel gas, except in the stomach. An emergency computer tomography (CT) scan performed without contrast media revealed marked intestinal dilatation mainly in the left abdomen, and a large amount of hemorrhagic ascites (Figure 2).

Figure 2 A: Pre-operative infantogram showing a gas shadow only in the stomach, with an absence of any distal gas shadow; B: Unenhanced abdominal CT showed meconium (arrow) in the distal small bowel, with mild fluid distension of the proximal small bowel.

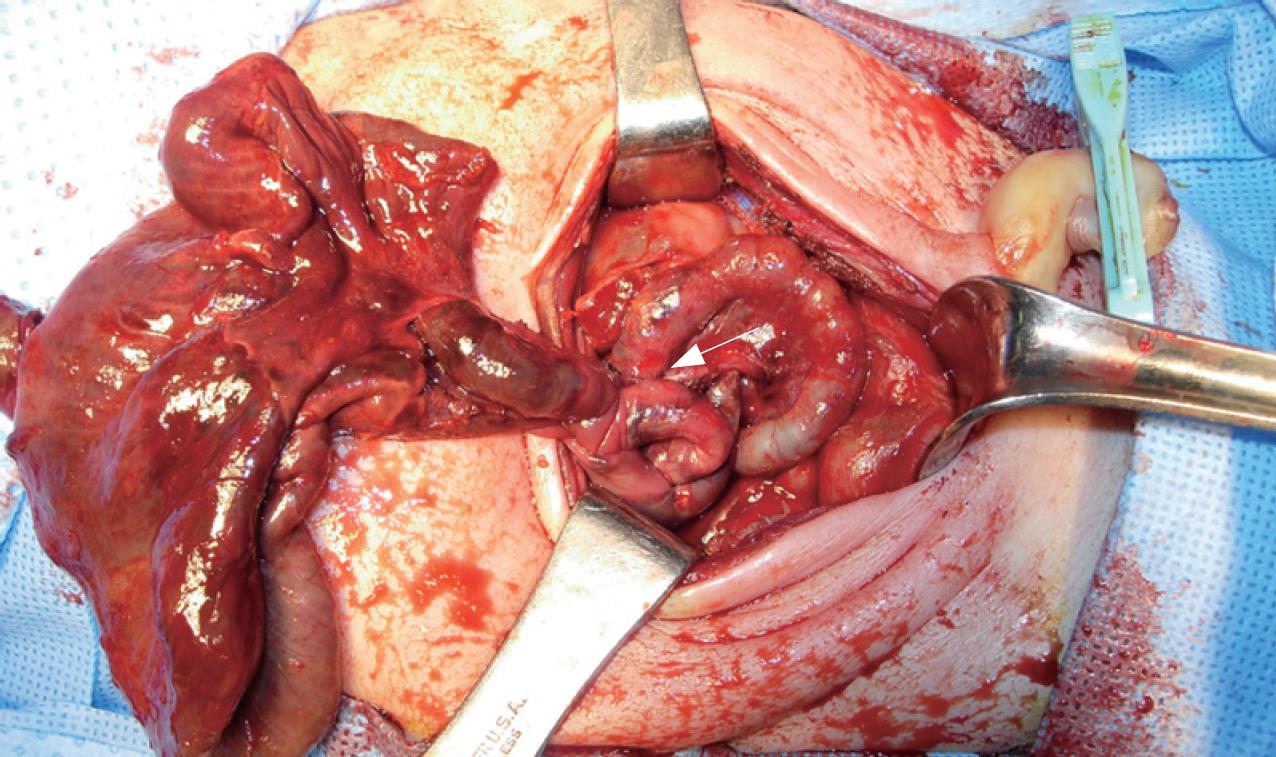

Exploration revealed a volvulus of the small bowel with extensive necrosis extending from 40 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz to 15 cm proximal to the ileocecal valve. The distended segment of intestine was twisted at the level of the narrow meconium filled distal ileum (Figure 3). There was no intestinal malrotation, mesenteric defect or atresia. After detorsion of the midgut volvulus, the thick meconium of distal ileum was irrigated by instilling saline with an 8-Fr rubber catheter. The involved loop was then resected and an end-to-oblique anastomosis was constructed between the dilated proximal and smaller distal bowels by manual anastomosis. On the fourth day after surgery, the patient required treatment with a gastrografin enema to loosen the persisting meconium ileus. A presumptive diagnosis of cystic fibrosis was made postoperatively, based on meconium ileus. There was no family history. To date, the baby has been screened, but all results have been negative. The infant made a remarkable recovery and was able to tolerate enteral feeding with a steady weight gain by four months after surgery.

Figure 3 On laparotomy, the infant was found to have a midgut volvulus with necrosis and perforation of the small bowel.

The small bowel was found to be twisted at the level of the narrow meconium-filled distal ileum (arrow).

DISCUSSION

Midgut volvulus is a surgical emergency frequently encountered in neonates. Most cases of volvulus in infants and fetus are associated with intestinal malrotation or congenital anomalies, such as omphalocele, gastroschisis, intestinal atresia or an annular pancreas[7]. On the other hand, the etiology of volvulus without malrotation is unknown, and associated anomalies are rare[5]. Several studies have shown that the absence of a segment of small bowel muscle or a mesenteric defect might be associated with this condition[8–11]. There is no clear explanation for the cause of this event in our patient, because laparotomy did not reveal any intestinal malrotation or congenital mesenteric anomalies. However, we suggest the fetal midgut volvulus and preterm labor was caused by the complicated meconium ileus. Intestinal volvulus might occur when the distended segment of the small bowel becomes twisted at the level of the narrow pellet-filled distal ileum. Gestational volvulus can result in ischemic necrosis, leading to fetal stress, which might activate the release of both adrenal and hypothalamic stress hormones. These might enhance placental, decidual and amniochorionic corticotrophin-releasing hormone release, while premature rupture of fetal membranes and preterm labor can be mediated by placental and membrane prostanoid release[1213].

Previous reports have described cases with midgut volvulus in which the fetal sonograms showed intestinal dilatation, a discrete cystic or solid abdominal mass, ascites, peritoneal calcification, polyhydramnios and, typically, the whirlpool or snail sign[1415]. Unfortunately, our patient did not show any definitive sonographic sign of midgut volvulus. Instead, retrospective analysis of the patient’s prenatal sonographic imaging revealed a coffee bean sign, which is a specific indicator of sigmoid volvulus in adult patients. Attention should always be paid to the risk of a midgut volvulus with such prenatal sonographic findings.

The nonenhanced CT scan performed after spontaneous vaginal delivery showed excessive hemorrhagic ascites, which was invisible during prenatal sonography. This suggests the bowel necrosis and meconium peritonitis may have developed rapidly during the spontaneous vaginal delivery. Rapid emergency Cesarean section or accelerated delivery should be considered for such expectant mothers who have a history of recurrent closed loop obstruction in the fetus, and who present with acute preterm labor, because the symptoms might occur perinatally with rapid progression to gangrene.

Delays in diagnosis are likely in such cases, as physicians tend to doubt or not suspect the possibility of intrauterine volvulus because it is so rare. Therefore, close prenatal monitoring is necessary if there is any suspicion of typical sonographic signs in the fetus. The adoption of more prompt delivery methods with exploration, avoidance of unnecessary special studies and appropriate postnatal intervention are all essential to reduce the likely morbidity and mortality of intrauterine volvulus associated with complicated meconium ileus.

Peer reviewers: Damian Casadesus Rodriguez, MD, PhD,

Calixto Garcia University Hospital, J and University, Vedado,

Havana City, Cuba; Takayuki Yamamoto, MD, Inflammatory

Bowel Disease Center, Yokkaichi Social Insurance Hospital,

10-8 Hazuyamacho, Yokkaichi 510-0016, Japan; Luigi Bonavina,

Professor, Department of Surgery, Policlinico San Donato,

University of Milano, via Morandi 30, Milano 20097, Italy