Published online Dec 21, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.7225

Revised: October 31, 2008

Accepted: November 7, 2008

Published online: December 21, 2008

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy of pegylated interferon α-2b (peg-IFNα-2b) plus ribavirin (RBV) therapy in Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis C (CHC) genotype Ib and a high viral load.

METHODS: One hundred and twenty CHC patients (58.3% male) who received peg-IFNα-2b plus RBV therapy for 48 wk were enrolled. Sustained virological response (SVR) and clinical parameters were evaluated.

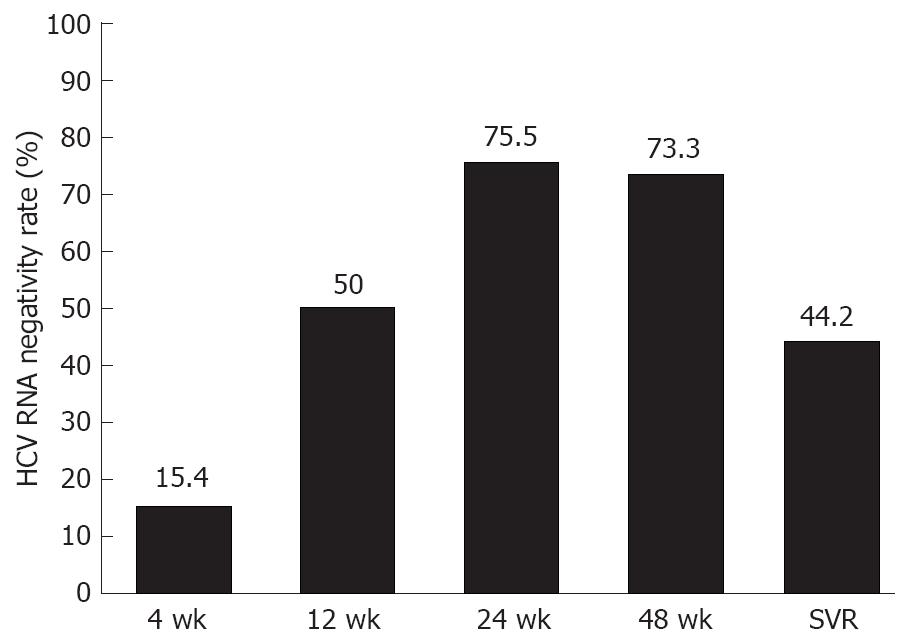

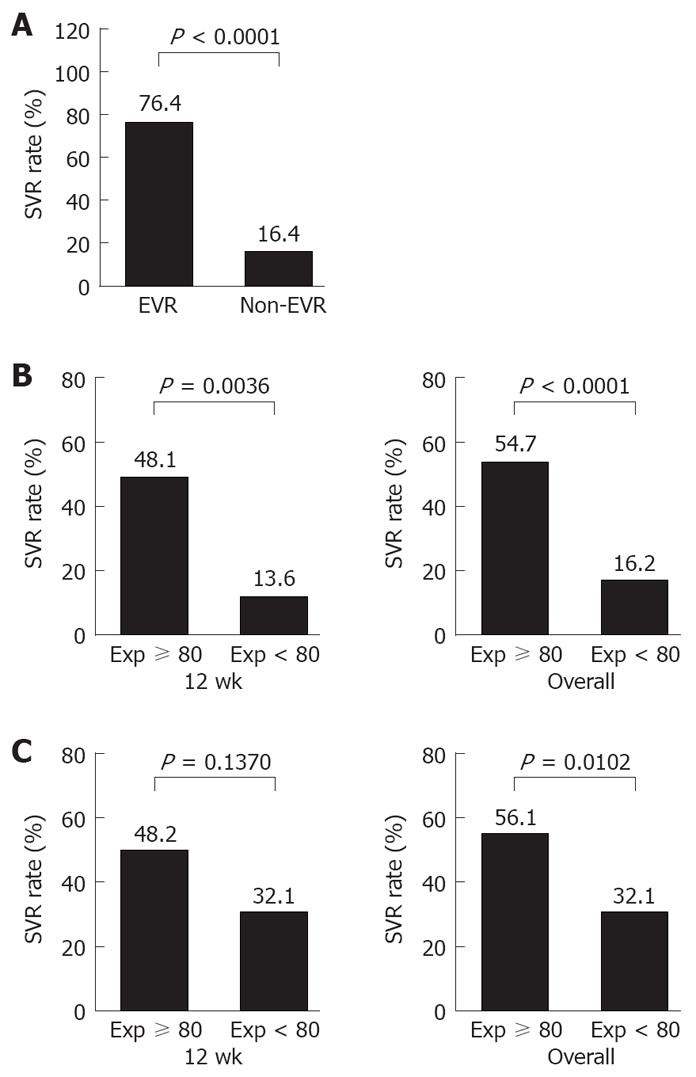

RESULTS: One hundred (83.3%) of 120 patients completed 48 wk of treatment. 53 patients (44.3%) achieved SVR. Early virological response (EVR) and end of treatment response (ETR) rates were 50% and 73.3%, respectively. The clinical parameters (SVR vs non-SVR) associated with SVR, ALT (108.4 IU/L vs 74.5 IU/L, P = 0.063), EVR (76.4% vs 16.4%, P < 0.0001), adherence to peg-IFN (≥ 80% of planned dose) at week 12 (48.1% vs 13.6%, P = 0.00036), adherence to peg-IFN at week 48 (54.7% vs 16.2%, P < 0.0001) and adherence to RBV at week 48 (56.1% vs 32.1%, P = 0.0102) were determined using univariate analysis, and EVR and adherence to peg-IFN at week 48 were determined using multivariate analysis. In the older patient group (> 56 years), SVR in females was significantly lower than that in males (17% vs 50%, P = 0.0262). EVR and adherence to Peg-IFN were demonstrated to be the main factors associated with SVR.

CONCLUSION: Peg-IFNα-2b plus RBV combination therapy demonstrated good tolerability in Japanese patients with CHC and resulted in a SVR rate of 44.3%. Treatment of elderly female patients is still challenging and maintenance of adherence to peg-IFNα-2b is important in improving the SVR rate.

- Citation: Kogure T, Ueno Y, Fukushima K, Nagasaki F, Kondo Y, Inoue J, Matsuda Y, Kakazu E, Yamamoto T, Onodera H, Miyazaki Y, Okamoto H, Akahane T, Kobayashi T, Mano Y, Iwasaki T, Ishii M, Shimosegawa T. Pegylated interferon plus ribavirin for genotype Ib chronic hepatitis C in Japan. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(47): 7225-7230

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i47/7225.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.7225

| No. of patients | 120 |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 70 (58.3) |

| Female | 50 (41.7) |

| Age (median, range, yr) | 54.8 ± 0.98 (56, 27-75) |

| Male | 54.1 ± 1.39 (55.5, 29-72) |

| Female | 55.8 ± 1.33 (56, 27-75) |

| Weight | 62.1 ± 1.09 (61.4, 35.0-99.8) |

| Body mass index (median, range, kg) | 23.7 ± 0.32 (23.6, 14.6-34.1) |

| Viral load (kIU kirocopies/mL) | 1510 (120->5000) |

| ALT (median, range, IU/L) | 89.4 ± 7.39 (67, 18-636) |

| WBC (median, range, /μL) | 5083 ± 136.6 (4900, 2400-9000) |

| Hemoglobin (median, range, g/dL) | 14.4 ± 0.12 (14.1, 11.8-17.2) |

| Platelet (median, range, × 103/μL) | 163.1 ± 4.71 (162.5, 8.1-33.2) |

| Interferon treatment history, n (%) | |

| Present | 41 (34.2) |

| Null-responder/relapser/unknown | 8/15/18 |

| Absent | 77 (64.2) |

| Unknown | 2 (1.6) |

| Factor | SVR patients (n = 53) | Non-SVR patients (n = 67) | P |

| Parameters before interferon treatment | |||

| Age (yr) | 52.5 ± 1.50 | 56.5 ± 1.26 | 0.0481 |

| Sex (Male:Female) | 35:18 | 35:32 | 0.1402 |

| Body mass index | 23.6 ± 0.48 | 23.8 ± 0.44 | 0.3611 |

| Viral load (kirocopies/mL, median) | 1500 | 1800 | 0.1963 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 108.4 ± 13.8 | 74.5 ± 7.04 | 0.0478 |

| WBC (/μL) | 5227 ± 201 | 4967 ± 186 | 0.2880 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 14.5 ± 0.18 | 14.3 ± 0.16 | 0.2352 |

| Platelet (× 103/μL) | 173 ± 7.7 | 155 ± 5.7 | 0.0630 |

| Parameters associated with treatment | |||

| EVR | 42/51 (82.4%) | 13/59 (22.0%) | < 0.0001 |

| Cumulative exposure to peg-IFN | |||

| 12 wk (≥ 80%/< 80%) | 38/41 (92.7%) | 41/69 (68.3%) | 0.0034 |

| Overall (≥ 80%/< 80%) | 35/41 (85.4%) | 29/60 (48.3%) | 0.0001 |

| Cumulative exposure to RBV | |||

| 12 wk (≥ 80%/< 80%) | 41/50 (82%) | 44/63 (69.8%) | 0.1882 |

| Overall (≥ 80%/< 80%) | 32/50 (64%) | 25/63 (39.7%) | 0.0138 |

| Factor | Coefficient | χ2 | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P |

| EVR (not achieved) | -2.725 | 19.325 | 0.066 (0.019-0.221) | < 0.0001 |

| Cumulative exposure to peg-IFN | ||||

| Overall (≥ 80%) | 2.392 | 6.600 | 10.934 (1.763-67.82) | 0.0102 |

| Constant | 1.294 | |||

| Factor | SVR patients (n = 20) | Non-SVR patients (n = 37) | P |

| Parameters before interferon treatment | |||

| Age (yr) | 64.0 ± 0.71 | 63.8 ± 0.73 | 0.6637 |

| Sex (male:female) | 16:4 | 18:19 | 0.0262 |

| Body mass index | 23.3 ± 0.56 | 23.6 ± 0.53 | 0.3973 |

| Viral load (kirocopies/mL) | 1500 | 1800 | 0.3616 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 94.5 ± 31.1 | 76.6 ± 11.0 | 0.3038 |

| WBC (/μL) | 5119 ± 313 | 4832 ± 223 | 0.3798 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 14.1 ± 0.23 | 14.1 ± 0.19 | 0.8473 |

| Platelet (× 103/μL) | 173 ± 12.4 | 151 ± 7.9 | 0.1434 |

| Parameters associated with treatment | |||

| EVR | 13/18 (72.2%) | 7/32 (21.9%) | 0.0008 |

| Cumulative exposure to peg-IFN | |||

| 12 wk (≥ 80%/< 80%) | 16/17 (94.1%) | 20/33 (60.6%) | 0.0183 |

| Overall (≥ 80%/< 80%) | 15/17 (88.2%) | 14/33 (42.4%) | 0.0023 |

| Cumulative exposure to RBV | |||

| 12 wk (≥ 80%/< 80%) | 14/20 (70%) | 20/34 (58.8%) | 0.5612 |

| Overall (≥ 80%/< 80%) | 8/20 (40%) | 13/34 (38.2%) | > 0.9999 |

In Japan, annual mortality due to liver cancer exceeds 30 000 and 75% of liver cancer is associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection[1]. The combination of pegylated interferon (peg-IFN) plus ribavirin (RBV) is one of the most effective therapies for chronic hepatitis C (CHC), and the effect of this combination is reported to be higher than conventional interferon[2,3]. However, the majority of Japanese CHC patients are infected with HCV genotype Ib and have a high viral load, and treatment with conventional interferon has its difficulties[4]. CHC patients in Japan tend to be older than CHC patients in other countries therefore, problems such as a higher incidence of liver cancer and lower tolerability to treatment have been observed[4,5]. The HCV strain and the efficacy of interferon treatment vary between races and countries[6,7]. Identification of the factors associated with treatment efficacy is extremely important, however, few studies involving large populations have reported on the treatment of Japanese CHC patients with pegylated interferon alpha-2b (peg-IFNα-2b) plus RBV[8,9]. In this study, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of peg-IFNα-2b plus RBV therapy in CHC genotype Ib patients with a high viral load. This treatment became available in Japan for health insurance approved treatment from December 2004. In addition, we attempted to identify predictive factors for treatment outcome.

One hundred and thirty CHC genotype Ib patients with a high viral load, who received peg-IFNα-2b plus RBV therapy in our hospital or our affiliated institutions between December 2005 and November 2006 were enrolled in this study. The diagnosis of CHC was based on the following criteria; HCV antibody positive, HCV-RNA positive and elevation of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity (> 35 IU/L) within 6 mo of screening. Exclusion criteria were leucopenia [white blood cell (WBC) count < 3000/μL], neutropenia [neutrophil (ne) count <1500/μL], thrombocytopenia [platelet (PLT) count < 90 000/μL], anemia [hemoglobin (Hb) < 12 g/dL], cirrhosis, creatinine clearance < 50 mL/min, uncontrolled mental disorder, severe heart or lung disease, or autoimmune disease. The study was approved by the ethical committee of Tohoku University according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave written informed consent before enrollment.

The patients received peg-IFNα-2b (Pegintron®; Schering-Plough, Kenilworth, NJ, USA) at a dosage of 1.5 mg/kg every week subcutaneously for 48 wk. Daily RBV (Rebetol®, Schering-Plough) was given orally for 48 wk and the dosage was adjusted according to weight (600 mg for ≤ 60 kg, 800 mg for 60 to 80 kg, 1000 mg for > 80 kg). Blood samples were obtained every four weeks and were analyzed for biochemical parameters including ALT and HCV RNA levels. The HCV genotype was determined using a kit. HCV genotype was determined by PCR using a mixed primer set derived from the nucleotide sequences of the NS5 region. HCV RNA levels were measured by quantitative RT-PCR (Amplicor, Roche Diagnostic Systems, CA, USA). HCV RNA negativity was evaluated by qualitative RT-PCR (Amplicor, Roche), which has a higher sensitivity than the quantitative method. The lower limit of the assay in the quantitative method was 5 KIU/mL (equivalent to 5000 copies/mL) and was 50 IU/mL (equivalent to 50 copies/mL) in the qualitative method. Early virological response (EVR) was defined as undetectable HCV RNA after 12 wk. Sustained virological response (SVR) was defined as undetectable HCV RNA at 24 wk after completion of treatment.

Fisher’s exact test and the Mann-Whitney U test were used to evaluate the parameters [age, sex, weight, body mass index (BMI), EVR, peg-IFN adherence, RBV adherence, HCV RNA, ALT, WBC, Hb, and PLT] to determine SVR. Quantitative data were divided into two groups using the median to examine the differences. We conducted multivariate analysis using binary logistic regression on the parameters which achieved statistical significance (P < 0.05) using univariate analysis. All analyses were performed using a statistical software package (StatView-J version 5.0, SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA).

The details of clinical background, blood biochemistry and virological data on the CHC patients who received peg-IFNα-2b plus RBV therapy are shown in Table 1. Seventy of 120 patients (58.3%) were male, and 50 patients (41.7%) were female. The mean age was 54.8 years, and the median age was 56 years. The mean age of males was 54.1 years, and the mean age of females was 55.8 years. The median BMI was 23.6. Seventy seven patients (64.2%) had no previous history of IFN treatment and 41 patients (34.2%) had been treated with IFN previously. Of these previously treated patients, 8 were null-responders (patients who did not achieve a virological or biochemical response during IFN treatment), 15 were relapsers, and 18 patients had no available virological response.

One hundred of 120 patients (83.3%) completed 48 wk of treatment and 24 wk of follow up. Using intention to treat (ITT) analysis, 53 patients (44.3%) achieved SVR. The rate of EVR was 50%. Response rate at the end of treatment was 73.3%. The transition rate of HCV RNA negativity with time is shown in Figure 1. Patients discontinued treatment due to depression in 3, neutropenia in 3, retinopathy in 2, anemia in 1, cutaneous reaction in 1, palsy in 1, HSV infection in 1, and no response to treatment in 7.

The association between SVR rate and the baseline clinical parameters before treatment or treatment-related factors was examined using univariate analysis. The following baseline factors were analyzed: age, sex, BMI, HCV RNA level, ALT, WBC, Hb, and PLT. A summary of these results is shown in Table 2. The mean ALT level in patients who achieved SVR was 108.4 IU/L, which was significantly higher than the ALT level of 74.5 IU/L in the non-SVR group (P = 0.0478). The PLT level in patients in the SVR group was 1.73 ×105/μL, which was higher than the PLT level of 1.55 ×105/μL in the non-SVR group (P = 0.063). To determine the factors associated with treatment outcome, we examined the relationship between the SVR ratio and achievement of EVR or adherence to peg-IFN and RBV. A summary of these results is shown in Table 2 and Figure 2. As shown in Table 2, the ratio of patients who achieved EVR was significantly higher in the SVR group than in the non-SVR group (P < 0.0001). The SVR rate in patients who achieved EVR was 76.4%, and this was significantly higher than the SVR rate in the non-EVR group which was 16.4% (P < 0.0001). The ratio of patients who received 80% or more of the scheduled dose of peg-IFN or RBV was significantly higher in the SVR group than in the non-SVR group. The SVR rate in patients who received 80% or more of the scheduled dose of peg-IFN was 48.1% (12th wk) and 54.7% (overall). The SVR rate in patients who did not receive sufficient peg-IFN was 13.6% (12th wk) and 16.2% (overall), and these were significantly lower than the group who had good adherence. The group with adequate adherence to RBV (overall) showed an SVR rate of 56.1%, which was significantly higher than the SVR rate of 32.1% in the poor adherence group (P = 0.0102). For the factors which were determined as statistically significant by univariate analysis, we subsequently conducted multivariate analysis. The results of this analysis are shown in Table 3. Using binary logistic analysis, EVR and adherence to peg-IFN were determined to be independent predictive factors for SVR.

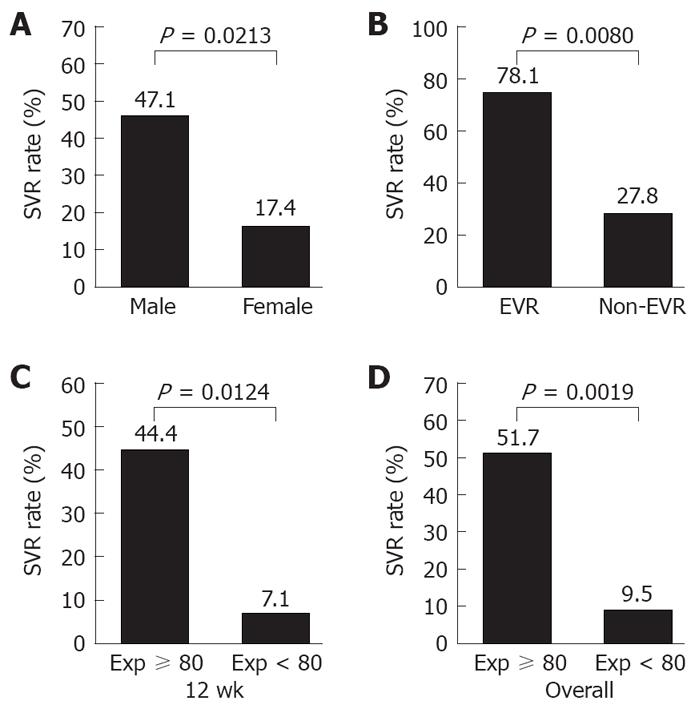

We examined a group of patients who were older than the median age (56 years). From the baseline factors obtained before treatment, sex was determined to be a parameter which may be associated with SVR (Table 4). The SVR rate in females was 17%, which was significantly lower than the SVR rate of 50% in males (P = 0.0262) (Figure 3A). From the factors associated with treatment outcome, EVR and adherence to peg-IFN were demonstrated to be significant (Figure 3B). In particular, the SVR rate in the group with poor adherence to peg-IFN was 7.1% (1 of 14) at the 12th wk and was 9.5% (2 of 21) at the end of treatment. These rates were extremely low compared with the SVR rate of 44.4% (12th wk) and 51.7% (overall) in the group with good adherence to peg-IFN (Figure 3C and D).

One hundred of 130 patients completed peg-IFNα-2b plus RBV combination therapy in our hospital and related institutions. Treatment was discontinued in 13 patients (10.8%) due to adverse effects. The treatment showed good tolerability in Japanese patients. A study of peg-IFNα-2b plus RBV combination therapy in Caucasian and African American CHC patients reported a discontinuation rate of 21%[10]. Another study on Japanese CHC patients reported a 21% discontinuation rate[9]. Although we cannot compare these studies directly, it seems that tolerability in this study was satisfactory. At least in a clinical setting, peg-IFNα-2b plus RBV was well tolerated in our study of Japanese patients.

In this study, age, ALT level, EVR achievement, and adherence to Peg-IFN and RBV were associated with a high SVR rate using univariate analysis. After multivariate analysis, EVR and adherence to peg-IFN were demonstrated to be associated with SVR. Of the baseline factors assessed before treatment, age, sex, WBC, α-feto protein level, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, and LDL-cholesterol have been reported to be associated with a high SVR rate following peg-IFNα-2b plus RBV therapy in CHC Japanese patients[8,11,12]. The results of this study were very similar to those of our study. Davis et al[13] reported that EVR was considered to be associated with SVR in patients with CHC treated with IFN. As a result of this study, EVR was found to be one of the factors which most influenced SVR rate in Japanese patients treated with peg-IFNα-2b plus RBV combination therapy. In our study of older patients (older than the median), sex, EVR, and adherence to peg-IFN were associated with SVR rate. The SVR rate in older females was remarkably low at 17.4% compared to the SVR rate in all females included in the study which was 36.0% (data not shown).

Adherence to peg-IFN was found to influence the SVR rate as a treatment-related factor in this study. SVR rates were low in patients who did not receive 80% or more of the intended dose of peg-IFN. The effect of adherence to IFN on SVR has been reported previously[13-15]. In a study on peg-IFNα-2a/RBV therapy in patients with HCV genotype I, it was reported that the SVR rate in cases who had a reduction in RBV dosage before the 20th wk was remarkably low[15]. Furthermore, a reduction in RBV dosage and/or peg-IFNα-2a dosage after the 24th wk did not influence the SVR rate[15]. On the other hand, a study on African American patients with HCV genotype I reported that a reduction in peg-IFNα-2b dosage influenced the SVR rate more than a reduction in RBV dosage[14]. In the current study, adherence to RBV up to the 12th wk did not significantly influence the SVR rate, but overall adherence to RBV significantly influenced the SVR rate. Unlike the reports on Caucasian and African American patients, it may be that overall adherence to RBV is important in Japanese patients.

It was notable that adherence to peg-IFNα-2b significantly influenced SVR in this study. In the patients who did not receive 80% or more of the intended dose by the 12th wk, the SVR rate decreased markedly. Adherence to peg-IFNα-2b at the 12th wk may be critical in determining whether the treatment should be continued. It is often difficult to maintain adherence to peg-IFNα-2b simply to improve the SVR rate, because IFN dosage and the hematologic adverse effects of this drug are problematic[16,17]. Recently, a 72-wk treatment protocol for late virological responders was reported[18,19]. Further examination of the impact of prolonged administration in patients with poor adherence to peg-IFNα-2b is needed.

In conclusion, peg-IFNα-2b plus RBV combination therapy demonstrated good tolerability in Japanese patients with CHC, and resulted in a SVR rate of 44.3%. Treatment of older female patients and maintenance of adherence to peg-IFNα-2b are important factors in improving SVR rate.

Pegylated interferon α-2b (peg-IFNα-2b) plus ribavirin (RBV) is a standard treatment of chronic hepatitis C globally. However, the impact of this treatment in an ordinary clinical setting in Asian patients is still unclear.

It is well documented that data from clinical practice is not comparable to those of clinical trials. This is believed to be derived from differences in recruited patients in phase II and III clinical trials and usual clinical settings (e.g. young vs elderly, highly motivated vs reluctant, etc).

The current study demonstrated that outcome is dependent on therapeutic adherence (> 80% of expected peg-IFN dosage). The overall treatment success [sustained virological response (SVR)] was 44.3%, almost equivalent to those in phase III clinical trials.

The total SVR rate was equivalent to clinical trials. The elderly, especially female patients showed a lower response to treatment. The reason for this is still unclear and future investigations are feasible in order to understand this observation.

SVR indicates sustained virological response, which means sustained (more than 24 wk after treatment) viral clearance from the infected host.

It is very important to describe the true clinical impact of global standard treatment in Asian races. Fortunately, the results were almost equivalent to those of other global regions. Although female patients seem to have a disadvantage with this treatment, these patients could have comparable results if adherence to both drugs is maintained.

Peer reviewers: Abdellah Essaid, Professor, Hospital Ibn Sina, Rabat 10100, Morocco; Ramesh Roop Rai, MD, DM (Gastro.), Professor & Head, Department of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, S.M.S. Medical College & Hospital, Jaipur 302019, (Rajasthan), India

S- Editor Li LF L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Umemura T, Kiyosawa K. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan. Hepatol Res. 2007;37 Suppl 2:S95-S100. |

| 2. | Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, Goodman ZD, Koury K, Ling M, Albrecht JK. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958-965. |

| 3. | McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Schiff ER, Shiffman ML, Lee WM, Rustgi VK, Goodman ZD, Ling MH, Cort S, Albrecht JK. Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1485-1492. |

| 4. | Higuchi M, Tanaka E, Kiyosawa K. Epidemiology and clinical aspects on hepatitis C. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2002;55:69-77. |

| 5. | Kiyosawa K, Umemura T, Ichijo T, Matsumoto A, Yoshizawa K, Gad A, Tanaka E. Hepatocellular carcinoma: recent trends in Japan. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S17-S26. |

| 6. | He XS, Ji X, Hale MB, Cheung R, Ahmed A, Guo Y, Nolan GP, Pfeffer LM, Wright TL, Risch N. Global transcriptional response to interferon is a determinant of HCV treatment outcome and is modified by race. Hepatology. 2006;44:352-359. |

| 7. | Luo S, Cassidy W, Jeffers L, Reddy KR, Bruno C, Howell CD. Interferon-stimulated gene expression in black and white hepatitis C patients during peginterferon alfa-2a combination therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:499-506. |

| 8. | Akuta N, Suzuki F, Kawamura Y, Yatsuji H, Sezaki H, Suzuki Y, Hosaka T, Kobayashi M, Kobayashi M, Arase Y. Prediction of response to pegylated interferon and ribavirin in hepatitis C by polymorphisms in the viral core protein and very early dynamics of viremia. Intervirology. 2007;50:361-368. |

| 9. | Hiramatsu N, Kurashige N, Oze T, Takehara T, Tamura S, Kasahara A, Oshita M, Katayama K, Yoshihara H, Imai Y. Early decline of hemoglobin can predict progression of hemolytic anemia during pegylated interferon and ribavirin combination therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatol Res. 2008;38:52-59. |

| 10. | Muir AJ, Bornstein JD, Killenberg PG. Peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C in blacks and non-Hispanic whites. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2265-2271. |

| 11. | Akuta N, Suzuki F, Kawamura Y, Yatsuji H, Sezaki H, Suzuki Y, Hosaka T, Kobayashi M, Kobayashi M, Arase Y. Predictors of viral kinetics to peginterferon plus ribavirin combination therapy in Japanese patients infected with hepatitis C virus genotype 1b. J Med Virol. 2007;79:1686-1695. |

| 12. | Akuta N, Suzuki F, Kawamura Y, Yatsuji H, Sezaki H, Suzuki Y, Hosaka T, Kobayashi M, Kobayashi M, Arase Y. Amino acid substitutions in the hepatitis C virus core region are the important predictor of hepatocarcinogenesis. Hepatology. 2007;46:1357-1364. |

| 13. | Davis GL, Wong JB, McHutchison JG, Manns MP, Harvey J, Albrecht J. Early virologic response to treatment with peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:645-652. |

| 14. | McHutchison JG, Manns M, Patel K, Poynard T, Lindsay KL, Trepo C, Dienstag J, Lee WM, Mak C, Garaud JJ. Adherence to combination therapy enhances sustained response in genotype-1-infected patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1061-1069. |

| 15. | Shiffman ML, Di Bisceglie AM, Lindsay KL, Morishima C, Wright EC, Everson GT, Lok AS, Morgan TR, Bonkovsky HL, Lee WM. Peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C who have failed prior treatment. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1015-1023; discussion 947. |

| 16. | Russo MW, Fried MW. Side effects of therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1711-1719. |

| 17. | Soza A, Everhart JE, Ghany MG, Doo E, Heller T, Promrat K, Park Y, Liang TJ, Hoofnagle JH. Neutropenia during combination therapy of interferon alfa and ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36:1273-1279. |

| 18. | Arase Y, Ikeda K, Tsubota A, Suzuki Y, Saitoh S, Kobayashi M, Kobayashi M, Suzuki F, Akuta N, Someya T. Efficacy of prolonged interferon therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis C with HCV-genotype 1b and high virus load. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:158-163. |

| 19. | Arase Y, Suzuki F, Tsubota A, Suzuki Y, Saitoh S, Kobayashi M, Akuta N, Someya T, Hosaka T, Kobayashi M. Sustained negativity for HCV-RNA over 24 or more months by long-term interferon therapy correlates with eradication of HCV in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1b and high viral load. Intervirology. 2004;47:19-25. |