INTRODUCTION

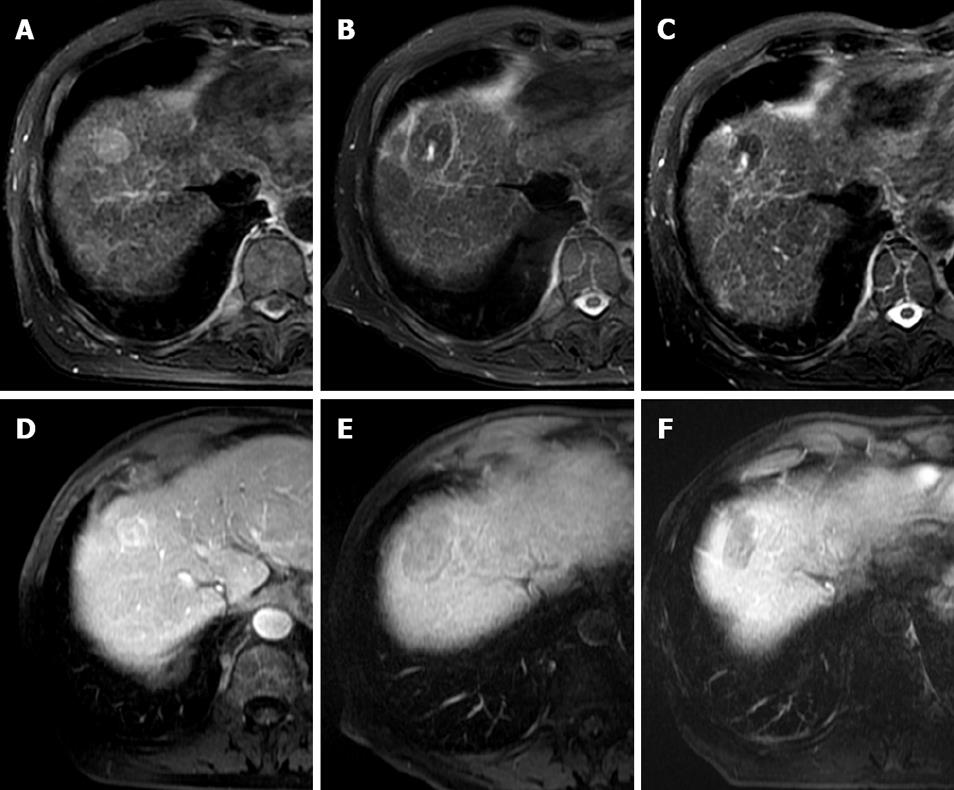

Figure 1 Typical MRI appearances pre and post laser ablation of a small HCC in a 73-year-old male patient with hepatitis C cirrhosis.

T2-weighted axial images demonstrate a high signal 2.5 cm segment VIII HCC (A). At one month post treatment (B) a typical low signal laser burn is demonstrated with high signal centre which has shrunk in size at 10 mo follow up (C). T1-weighted post contrast images of the same lesion demonstrate heterogeneous arterial enhancement pre-treatment (D), with non-enhancing scar at 1 mo (E) and persistent non-enhancement at 10 mo (F).

Surgical resection or transplantation have in the past been considered the gold standard for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The overall resectability rate for such lesions is very low due to a combination of underlying chronic liver disease, lesion location and multifocal nature of HCC. Similarly, surgical resection carries a significant associated morbidity and mortality, as well as a disease recurrence rate of up to 75%[1,2]. Local thermal ablative techniques have gained popularity over the last decade proving to be an effective and safe alternative in many patients. These techniques are also cost effective in comparison to other treatments and are able to maximise the preservation of surrounding liver parenchyma whilst minimizing in-patient hospitalization[3]. Laser ablation (LA) represents one of a range of currently available loco-ablative techniques with the majority of reported data coming from Italy, Germany and the UK.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES & TECHNIQUES

The term laser ablation refers to the thermal tissue destruction of tissue by conversion of absorbed light (usually infrared) into heat and includes various technical variations on this theme including “laser coagulation therapy”, “laser interstitial tumour therapy” and “laser interstitial photocoagulation”[4].

Infrared energy penetrates tissue directly for a distance of between 12-15 mm, although heat is conducted beyond this range creating a larger ablative zone[5]. Optical penetration has been shown to be increased in malignant tissue compared to normal parenchyma[6]. Temperatures above 60°C cause rapid coagulative necrosis and instant cell death, but irreversible cell death can also be achieved at lower hyperthermic temperatures (> 42°C) although longer durations (30-60 min) are required[7]. Temperatures above 100°C will cause vaporisation from evaporation of tissue water and above 300°C tissue carbonisation occurs. Overheating is thus best avoided as carbonization decreases optical penetration and heat conduction and limits the size of lesion produced[6]. Local tissue properties, in particular perfusion, have a significant impact on the size of ablative zone. Highly perfused tissue and large vessels act as a heat sink, as laser light is absorbed by erythrocytic heme and transported from the local area[8]. This phenomenon makes native liver parenchyma relatively more resilient to LA than tumor tissue and is the basis for the use of hepatic inflow occlusion techniques in conjunction with laser therapy such as local arterial embolization[9,10].

The most widely used device for LA techniques is the Nd-YAG (neodymium: yttrium-aluminium-garnet) laser with a wavelength of 1064 nm, because penetration of light is optimal at the near-infrared range of the spectrum[11]. More recently, more compact, less expensive diode lasers with shorted wavelengths (800-980 nm) have been used, although the lower tissue penetration produces a smaller volume of destruction.

Light is delivered via flexible quartz fibres of diameter from 300-600 μm. Conventional bare tip fibres provides a near spherical lesion of about 15 mm diameter at their ends, but have been largely replaced by interstitial fibres which are quartz fibres that have flat or cylindrical diffusing tips and are 10-40 mm long, providing a much larger ablative area of up to 50 mm[12,13]. The use of beam splitting devices allows the use of up to four fibres at once with corresponding increase in ablative volume, but requires multiple fibres to be placed and only works effectively at lower powers. Beam splitters are, therefore, rarely used with interstitial fibres. With increasing laser power, comes better light transmission and larger ablative zones. However, it also causes increased local temperature rise, risking overheating and carbonization of the adjacent tissue. The use of water cooled laser application sheaths allows a higher laser power output (up to 50 W compared with 5 W) while preventing carbonization[14]. Thus, the use of multiple water-cooled higher power fibres allows ablative zones of up 80 mm diameter. Water cooled sheaths do require wider bore cannulas, but are commonly placed via a coaxial dilation system from an 18 G puncture.

IMAGE GUIDANCE

A range of different imaging modalities have been used to guide percutaneous laser ablation techniques determined largely by local experience and resource availability. Ultrasound (US) guided needle placement has the advantage that it is quick, portable, and widely available, as well as being familiar to those used to performing US guided biopsies. The major disadvantage is that it offers little reliable indication of the temperature or extent of the ablative zone being created.

In contrast, magnetic resonance (MR) guided LA, often in conjunction with liver specific contrast agent, e.g. teslascan [mangafodipir trisodium (MnDPDP) Nycomed Imaging, Oslo, Norway], offers real time thermal mapping that allows the operator to visualise the size, location and temperature of the ablation zone[15,16]. This technique tends to be used in conjunction with the higher power water cooled laser systems as the increased energy (for example 40 000 J) can be delivered in a safe and controlled manner[17,18]. By contrast, US guided laser systems tend to use multiple lower power laser fibre with a lower total energy delivery[19]. However, MR guided LA is limited by machine availability and represents a longer procedure.

Thermal imaging can be performed on most MR systems, with thermal changes being easier to demonstrate as magnet field strength increases. There are several methods of measuring tissue temperature changes with MR. The simplest, and most widely used technique, is measuring alterations in T1 value of tissues which decreases in a linear relationship with increasing tissue temperature up to approximately 55°C[20,21]. Techniques that measure changes in the tissue diffusion coefficient are more accurate, up to ± 1°C, but require long acquisition times and, therefore, suffer from patient motion artifacts[22]. Another technique measures changes in the proton resonance frequency shift (phase shift). Again this measures temperature changes very accurately, but is not suitable for use in fatty tissue and is less suited to open MR units as it requires a homogenous magnetic field[23]. All of these techniques are best used in conjunction with subtraction techniques, i.e. pretreatment image subtraction from heating image, which allows very accurate assessment of lesion size, but is sensitive to motion and misregistration artifacts[24].

In addition to thermometry, the use of “open” MR magnets allows real time imaging of needle placement in a truly multiplanar manner [unlike computed tomography (CT)] and is not limited by the presence of bone or gas (unlike US) with the disadvantage that the inherent lower field and gradient strengths of open systems reduce image quality and increase scan time. Conventional closed magnets require fibre placement using CT or US with subsequent transfer into the MR scanner for thermal mapping. This has the disadvantages involved with patient transfer mid procedure, but provides faster imaging and thermal mapping than an open system. The use of MR guidance and thermometry is currently only feasible with LA systems, as it uses a completely metal free system and does not produce any radiofrequency (RF) interference. Most RFA systems are currently not suitable for MR usage, both because of steel within the electrodes and the degradation of image quality by extraneous RF noise produced by the RF generators. Although MR compatible systems have been developed in practice the RF noise remains problematic[16].

There is variation across the literature regarding patient analgesia during laser ablation with some groups providing conscious sedation and intravenous analgesia whilst others preferring general anaesthesia. General anaesthesia allows higher tolerable energy delivery and better control of respiration, but has significant resource implications, has its own associated morbidity rates and may affect patient inclusion/selection.

The use of local ablative techniques in combination with surgery has been explored using RFA and cryoablation[25]. While technically feasible, there is little recently published experience of LA usage at laparoscopy or laparotomy.

PATIENT SELECTION

Selection criteria vary from unit to unit dependant on the technique used and facilities available, but are broadly similar to those for other local ablative techniques and are based on size, number and site of HCC in patients who are deemed unsuitable for surgical resection or transplant. Laser ablation is also considered a valid interim treatment while awaiting transplant surgery. Patients are generally considered if there are less than 5 lesions of 5 cm or less. Lesions larger than this can be considered, particularly if using a high power system, though they may require more than one treatment. The ideal lesions are those less than 3 cm and deep within liver parenchyma. Lesions adjacent to major vessels, biliary ducts, bowel or diaphragm can be treated with caution. MR guided techniques allow confident ablation of anatomically more problematic lesions with the use of real time thermometry and multiplanar MR targeting. Severe liver disease (Childs C) and coagulopathy are relative contraindications to be considered in each individual patient and extra hepatic disease is generally considered an absolute contraindication.

EFFECTIVENESS

Several factors make interpretation of published outcome data difficult. While the majority of patients have HCC secondary to viral hepatitis, they represent a diverse cohort in terms of disease severity. Differing laser fiber systems with differing energy delivery levels make comparison of both efficacy and complication rates difficult to compare. Again, the range of imaging modalities used at follow-up, combined with a variety of definitions of treatment success, make comparison of data difficult.

Lastly, current guidelines suggest that formal tissue biopsy of HCC is not recommended in every case due to potential risks of tumour seeding. Many groups, therefore, assume the diagnosis of HCC based on history, imaging appearances and rising alpha fetoprotein (αFP) levels. The inevitable occasional inclusion of some lesions that are not in fact HCCs may, therefore, favorably skew outcome data.

When assessing the literature regarding efficacy of laser ablation, a clear distinction must be drawn between primary effectiveness rates and long term outcome rates. Primary effectiveness relates to complete lesion ablation as assessed by either CT or MR at a defined point post procedure and after a defined number of treatments. This does not necessarily correspond to improved long term outcomes. However, data regarding long term survival rates for LA is scarce and in part reflects the novelty of the treatment and the rapid advances in technology, particularly in relation to the laser fibres. Pacella et al[26] reported long term survival rates of 89%, 52% and 27% for 1, 3 and 5 years, respectively, in a series of 169 sub 40 mm lesions in 148 patients (144 biopsy proven HCC) treated with 239 sessions. They quote an overall 82% complete lesion ablation rate[26]. The same group reported an earlier series of 74 patients with 92 biopsy proven sub 4 cm HCCs with a complete ablation rate of 97% and survival rates of 99%, 68% and 15% for 1, 3 and 5 years, respectively[27] (Figure 1).

Results reported by those groups using water cooled higher power MR guided laser ablation have been promising. Eichler et al[28] reported mean survival rates of 4.4 years (95% CI: 3.6-5.2) in a series of 39 patients with 61 presumed HCCs with a complete ablation rate of 97.5%. Although the same groups have provided compelling long term survival data for the ablation of hepatic metastases, no such data has to date been published for HCC ablation[29].

COMPARISON WITH OTHER ABLATIVE TECHNIQUES

A report by Ferrari et al[30] is the only randomized prospective study comparing LA with RF ablation. They treated 81 cirrhotic patients with 95 biopsy proven, sub 4 cm HCCs. Two matched groups were randomised to US guided RF or LA under general anaesthetic. LA was via multiple 5 W fibres delivering a maximum of 1800 J per fibre per treatment. Post treatment, lesions were evaluated with CT. They reported no significant difference overall in survival rates between the two techniques with cumulative rates of 91.8%, 59.0%, and 28.4% at 1, 3 and 5 years, respectively. They did, however, demonstrate a statistically significant higher survival rate for RFA over LA for Child A patients (P = 0.9966) and nodules ≤ 25 mm (P = 0.0181). They reported no significant complications[30]. This work added to the same groups’ previous published improved survival rates in patients treated with LA, compared to those treated with either transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) or percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI)[31].

COMBINATION WITH TACE

The rationale of combining LA with TACE is attractive, particularly for large lesions. Pacella et al[19] described the use of LA followed by TACE in the treatment of 30 large (3.5-9.6 cm) HCCs. They achieved 90% ablation rate with survival rates of 92%, 68% and 40% at 1, 2, and 3 years, respectively. No significant complications were reported, leading the authors to conclude that combination therapy was a safe and effective palliative therapy in the treatment of large HCCs[19]. Ferrari et al[32] supported this suggestion demonstrating improved ablation rates and survival in patients with HCCs > 5 cm given combination treatment over LA alone.

COMPLICATIONS

Reported complication rates for laser ablation compare favourably to surgical rates.

Arienti et al[33] reported complication rates for 520 patients, with 647 presumed HCCs treated with 1004 laser sessions (local anaesthetic, US guided). They report 0.8% deaths and 1.5% major complication rate. An earlier report by Vogl et al[34] included 899 patients (of which 42 had HCC), with 2520 lesions treated with 2132 laser sessions (local anaesthetic, CT/MRI guided) and reported 0.1% mortality and 1.8% major complication rate. Included in the major complications were liver failure/segmental infarction, hepatic abscess/cholangitis, bile duct injury, and haemorrhage (intrahepatic/peritoneal/gastrointestinal). Both groups reported common side effects of asymptomatic pleural effusion (7.3% & 6.9%), post procedural fever (33.3% & 12.3%) and severe pain (7.5% & 11.5%). While tumor seeding after percutaneous biopsy and ablative therapies is well recognized, it has rarely been reported after laser ablation and neither of the above groups reported this complication.

CONCLUSION

LA of HCC remains a safe and effective local therapy for patients in which surgical resection is not possible or appropriate. Nevertheless, further data from randomized trials are required to establish long term survival rates, particularly for higher power water cooled systems before the treatment can be fully validated as a standard treatment. Further data is required to establish its role in combination therapy, either with other percutaneous treatments and/or surgery. At this stage, RFA remains the standard of care, but as the technology and experience progress the technique will be in a position to be randomised against RFA as an effective alternate primary treatment of HCC in an attempt to establish equivalent efficacy/long term survival.

Peer reviewer: Markus Peck-Radosavljevic, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine IV, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, A-1090 Vienna, Austria

S- Editor Xiao LL L- Editor Rippe RA E- Editor Lin YP